阿爾巴尼亞人

阿爾巴尼亞人(阿爾巴尼亞語:),是主要分布在東南歐巴爾幹半島上的一個民族,多使用阿爾巴尼亞語並在奥斯曼帝国时期开始信奉伊斯兰教,但也有大量保留了东正教信仰的阿尔巴尼亚人。阿爾巴尼亞人主要分布在阿爾巴尼亞,另在科索沃、北馬其頓、希臘也有大量分布。也有一些阿爾巴尼亞人在海外散居(土耳其、埃及、香港),當中以土耳其的阿裔社群為最龐大。義大利也是阿爾巴尼亞移民的1個主要集中區,這是由於南斯拉夫解體時期因內戰、經濟問題,大量居於科索沃、阿爾巴尼亞的阿爾巴尼亞人隔海逃離當時飽受科索沃戰爭的科索沃、90年代民主化開放政策之初的阿爾巴尼亞。也有一些是阿爾巴尼亞化的斯拉夫人。不少在其他巴爾幹半島國家定居的阿爾巴尼亞人,祖先曾是土耳其新軍。

| 阿爾巴尼亞人 Shqiptarët | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

| 總人口 | ||||||||||||||||

| 1200萬 | ||||||||||||||||

| 分佈地區 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2,509,876 (2016)[1] | ||||||||||||||||

| 1,549,323 (2016)[2] | ||||||||||||||||

| 900,0002[3][4] | ||||||||||||||||

| 509,083 | ||||||||||||||||

| 300,000[5][6][7] | ||||||||||||||||

| 30,439 (2011)[8] | ||||||||||||||||

| 17,513 (2011)[9] | ||||||||||||||||

| 10,000 (2010)[10] | ||||||||||||||||

| 4,020[11] | ||||||||||||||||

| 800,0001[12] | ||||||||||||||||

| 150,000[13] | ||||||||||||||||

| 200,000[14][15] | ||||||||||||||||

| 54,000[16] | ||||||||||||||||

| 30,000[17] | ||||||||||||||||

| 28,212[18] | ||||||||||||||||

| 20,000[19] | ||||||||||||||||

| 20,000 | ||||||||||||||||

| 10,000 | ||||||||||||||||

| 8,223[20] | ||||||||||||||||

| 8,214[21] | ||||||||||||||||

| 30,000[22][23] | ||||||||||||||||

| 5,000[24] | ||||||||||||||||

| 5,809 (2011) | ||||||||||||||||

| 1,400 (2013) | ||||||||||||||||

| 193,813[25] | ||||||||||||||||

| 28,270[26] | ||||||||||||||||

| 11,315[27] | ||||||||||||||||

| 40,000[28] | ||||||||||||||||

| 語言 | ||||||||||||||||

| 阿爾巴尼亞語 | ||||||||||||||||

| 宗教信仰 | ||||||||||||||||

羅馬天主教(意大利阿爾巴尼亞拉丁禮教會)、阿爾巴尼亞正教會、基督新教 无宗教 | ||||||||||||||||

民族分佈

大約有700萬阿爾巴尼亞人居住在巴爾幹半島,其中約一半居住在阿爾巴尼亞,另一半分佈在科索沃、黑山、塞爾維亞、北馬其頓共和國、希臘之間、波斯尼亞、保加利亞、克羅地亞、羅馬尼亞和斯洛文尼亞。 阿爾巴尼亞估計有3百萬居民,其中阿爾巴尼亞人佔約95%。[29]

科索沃

科索沃

自從中世紀以來,阿爾巴尼亞在科索沃和毗鄰的托普卡和摩拉瓦地區就已經存在。1878年,貝爾格萊德公國得到柏林國會給予的塞爾維亞南部的托普卡和莫拉瓦地區,這裏的塞爾維亞人驅逐居住在這裏的阿爾巴尼亞人,被驅逐的阿爾巴尼亞人大部分定居在科索沃。在科索沃他們的後代被稱爲穆罕默德,意為流亡。

蒙特內哥羅

蒙特內哥羅

阿爾巴尼亞人在該國的人口組成中大約佔了4.91%,多數居住在西南方還有南方。他们主要居住在以下這些城市:

- 乌尔齐尼 (71%)

- 普拉夫 (19%)

- 巴尔 (6%)

- 波德戈里察 (5%)

- 罗扎耶 (5%)

蒙特內格羅的阿爾巴尼亞人屬於蓋格阿爾巴尼亞人[30]。最大的阿爾巴尼亞人城市是乌尔齐尼。

北馬其頓

北馬其頓

阿爾巴尼亞人是北馬其頓最大的少數族羣。根據2002年的人口調查,超過兩百萬的居民當中有百分之二十五是阿爾巴尼亞人。境內多數阿爾巴尼亞人居住在该国西北部。阿爾巴尼亞人主要分布在以下城市[31]:

- 泰托沃(70.3%)

- 戈斯蒂瓦尔(66.7%)

- 德巴尔(58.1%)

- 斯特鲁加(56.8%)

- 基切沃(54.5%)

- 库马诺沃(25.8%)

- 斯科普里(20.4%)

希腊

希腊

大概有二十七萬至六十萬阿族人生活在希臘,是該國最大的移民社羣。自1991年阿爾巴尼亞社會主義民主共和國崩潰以來他們就以經濟移民的身份來到希臘。

義大利

義大利

在意大利南部,有約260,000位阿爾巴尼亞人,這個小型聚落被稱作阿尔伯雷什人[32]。15、16世紀以來,因爲當時奧圖曼帝國在巴爾幹半島的擴張使他們流離失所,因此遷移到現在的位置並且定居下來。當時的那不勒斯王國和西西里島王國(當時都在阿拉貢共和國的統治之下)給予這些阿爾巴尼亞人庇護,並讓他們有自己的村莊。這些阿爾巴尼亞人主要散佈在意大利南部還有西西里島上。

1990年阿爾巴尼亞國內的共產政權瓦解之後,意大利便成爲阿爾巴尼亞人移民的最主要目的地。這有兩個原因,一是因爲地理距離,第二是因爲當阿爾巴尼亞還處於共產政權的時候,意大利是西方的象徵。

宗教信仰上,不同于在阿尔巴尼亚以及周边国家的宗教情况,在意大利的阿尔巴尼亚族绝大多数人都是天主教徒。

其他歐洲國家

大約有一百萬阿爾巴尼亞人散佈在歐洲其他地方,主要是來自1999年科索沃戰爭中的難民。當時許多阿爾巴尼亞人向德意志聯邦共和國尋求庇護。1999年末,在德國的阿爾巴尼亞人已有480,000人,而約有100,000在戰後自願或是非自願的回到科索沃。 此外,在瑞士約有54,000阿爾巴尼亞人,英國則有約100,000人。

西亞

早期在土耳其的阿爾巴尼亞人是在奧斯曼帝國時期以經濟移民的身份往土耳其共和國遷徙的,這是由於在巴爾幹國家內阿爾巴尼亞族人所遭受的社會政治歧視和暴力所導致的。[33]根據2008年安納托利亞東土耳其三所大學的學者為土耳其國家安全委員會編寫的報告,阿爾巴尼亞後裔大約有一百三十萬人生活在土耳其。[34]根據這項研究,超過50萬阿爾巴尼亞後裔仍然承認他們的祖先和他們的語言,文化和傳統。[35]

在埃及,有18,000名阿爾巴尼亞人,大多數說托斯克(Tosk)方言。[36]許多人是穆罕默德·阿里·帕夏的後裔。穆罕默德·阿里·帕夏以阿爾巴尼亞人的身份成為瓦利(奥斯曼帝国的行政头衔),而且他自稱是埃及和蘇丹的科赫迪(相當於督撫)。除了他所建立的王朝,前埃及和蘇丹貴族的很大一部分是阿爾巴尼亞裔。 隨著伽馬爾·阿卜杜勒·納賽爾和阿拉伯民族主義的興起,阿爾巴尼亞人組成的社羣最後被迫離開。[37]阿族人曾經在阿拉伯國家,如敘利亞,黎巴嫩等地[38],伊拉克,約旦和約五個世紀以來作為奧圖曼土耳其帝國統治下的產物。

美洲、非洲、亞洲、大洋洲

根據2010的美國社區調查,有將近20萬名阿爾巴尼亞人居住在美國;澳大利亞和紐西蘭共有大約22000位阿爾巴尼亞人;而在東亞的阿爾巴尼亞人則相對較少,但東亞地區內的國際城市如在香港也有約100名阿爾巴尼亞人分佈。

語言

阿尔巴尼亚人使用阿尔巴尼亚语( {IPA|/ˈɟuˌha ˈʃciˌpɛ/}} 或 [ʃcip])属印欧语系,与周边的希臘語族和斯拉夫语族语言明显不同。使用者約五百萬人,其他東南歐國家如蒙特內哥羅的阿爾巴尼亞族裔亦有使用。它有幾種方言,之间有一些区别:托斯克方言,用于阿尔巴尼亚南部和中部以及在希腊西北部的阿尔巴尼亚少数群体中;盖格方言使用于阿尔巴尼亚北部(包括首都地拉那)以及科索沃和北馬其頓的阿尔巴尼亚人中。阿爾巴尼亞語可能主要来源于二千年前用于该地区的伊利里亞语,以及其他一些印欧语系的亚族中。

标准阿尔巴尼亚语有7个元音和29个辅音。其中盖格方言有长元音和鼻化元音,而托斯克方言没有,并且中央元音 ë 在词尾脱落。重音大部分固定在最后一个音节上。

地理環境

地理

阿尔巴尼亚人聚居地位於東南歐巴爾幹半島西岸,包括阿尔巴尼亚共和国全境、除北科索沃以外的科索沃和北马其顿的西北部Ilirida,東南鄰希臘,西瀕亞得裏亞海和伊奧尼亞海,隔奧特朗托海峽與意大利相望。海岸線長472公里 阿爾巴尼亞全境四分之三的地區是山地和丘陵,地勢東高西低,東部邊境的科拉比山海拔2,764米,為全國最高峰。西部沿海平原僅寬20~30公裏。

阿爾巴尼亞地圖

阿爾巴尼亞地圖 阿尔巴尼亚卫星照片

阿尔巴尼亚卫星照片 阿尔巴尼亚人占多数的大阿尔巴尼亚

阿尔巴尼亚人占多数的大阿尔巴尼亚

氣候

大部地區屬於地中海氣候,而東部和北部山區屬溫帶大陸性氣候及高山氣候,冬冷夏熱。降雨量充沛,年均為1300毫米,但是夏天幹燥。一年中七月最熱,平均氣溫24度,最冷為一月份,平均氣溫7度。

歷史沿革

古代

最早有關阿爾巴尼亞人的描述是出現在11世紀的保加利亞文獻[39]在歷史記錄中,首次無可爭議地提及阿爾巴尼亞人是在1079-1080年間首次在從拜占庭來的,並且是由拜占庭歷史學家邁克爾·阿塔利亞斯(Michael Attaliates)所作的著作,他把阿爾巴尼亞稱為1043年參與對君士坦丁堡政權的反抗的一部分。 然而,有爭議的是,這個事件中的“阿爾巴尼亞”究竟是指在種族意義上的阿爾巴尼亞族人,還是“阿爾巴諾尼”,就是說一個古老的、來自西西里島的諾曼人(因爲當時意大利也有一個名爲“Albanoi”的部落。)目前還眾說紛紜.

奧斯曼帝國時期

在奧斯曼帝國的建立之初,當時的地緣政治景觀以分散的小王國為特徵。 1415年,奧斯曼帝國在阿爾巴尼亞全國各地建起了他們的駐軍,到1431年對阿爾巴尼亞大部分地區建立了正式的管轄權。[40]然而,在1443年,一場持續的反抗在阿爾巴尼亞國家英雄斯坎德伯格的領導下,一直持續到1479年,多次擊敗由蘇丹穆拉德二世和梅罕邁德二世領導的奧斯曼帝國軍隊。

阿爾巴尼亞國民覺醒

到了19世紀70年代,當時的領導者,Porte,他崇高的改革宗旨顯然地已經失敗了。奧斯曼帝國的“土耳其枷鎖”形像在帝國內的巴爾幹人民的民族主義神話中越來越固定,因此他們走向獨立的步伐也加快了。 由於伊斯蘭影響力較高,阿族人的內部社會分裂,在此同時,他們也懼怕他們將會失去阿爾巴尼亞人口稠密的土地到那些巴爾幹半島的新興國家如,塞爾維亞,黑山,保加利亞和希臘的手中。這些都是阿爾巴尼亞人中希望從奧斯曼帝國分裂的原因。[41]

獨立

由於當時巴爾幹同盟與奧斯曼帝國的戰爭獲勝,當時塞爾維亞王國想要進一步奪取阿爾巴尼亞人的土地,與塞爾維亞敵對的奧匈帝國不願意讓塞爾維亞人得到土地,因此便協助阿爾巴尼亞的民族主義者伊斯梅爾·捷馬利(獨立後成為阿爾巴尼亞親王國第一任總理)在阿爾巴尼亞南部城市發羅拉宣佈獨立,阿爾巴尼亞也因此在1912年11月28日從奧斯曼帝國獨立。1913年許多歐洲國家承認阿爾巴尼亞的國境。塞爾維亞王國喪失阿爾巴尼亞後,卻獲得有大量阿爾巴尼亞人居住的內陸地區科索沃和今天馬其頓的西北部作補償。這個決定為1996-1999年的科索沃戰爭埋下了伏線。

近代

第一次世界大戰中阿爾巴尼亞再次被占領。1915年奧匈帝國占領了阿爾巴尼亞北部,意大利占領其東南部,法國占領了都拉斯。在1919年的巴黎和會上,阿爾巴尼亞的代表團達到重建阿爾巴尼亞的目的。雖然如此希臘和意大利不願從它們占領的地區撤兵,直到1920年他們被阿爾巴尼亞人驅逐。 戰後阿爾巴尼亞的情況依然動蕩不安。各地酋長爭權,政府交替頻繁。1925年起艾哈迈德·佐格成為阿爾巴尼亞政治中的主要支配人,1928年他加冕為阿爾巴尼亞國王。出自經濟原因他很快就成為意大利法西斯的追隨者。1939年4月7日意大利吞併阿爾巴尼亞,佐格下台。

二戰時,德國於1941年南下侵佔南斯拉夫及希臘,之後德國將南斯拉夫的科索沃併入阿爾巴尼亞。1943年意大利向盟軍投降後阿爾巴尼亞就被德軍佔領。

阿爾巴尼亞共產黨於1941年組建,1944年11月德軍主力撤出阿爾巴尼亞時,阿共在不靠外國的幫助下解放他們的國家。

社會、家庭與婚姻

社會組織

阿爾巴尼亞有一個複雜的社會結構。它的基礎是家庭,它可以作為一個社會單元,也是整個社會經濟的接合點。在過去,大城市以及農業地區主要都是以大家庭的形式爲主,有時候甚至可以多達50人。而擁有牲口的畜牧地區則多以小家庭爲主。

婚姻

一般來說阿爾巴尼亞人結婚需要經過一定的婚姻儀式。尋找婚姻對象的時候通常是藉由親戚朋友的牽線,當然到了現今的阿爾巴尼亞,外國人與阿爾巴尼亞人通婚的個案也有不少且越趨普遍。而由於有部分的阿爾巴尼亞人信奉伊斯蘭信仰的關係,新郎或許需要支付一筆不小數目的聘金才能娶到新娘(僅限於虔誠的穆斯林新人),但現時這些儀式也變得十分世俗化和西化,新一代的阿爾巴尼亞新人甚至會希望舉辨一個具創意或新穎的婚禮。婚禮大多由親戚、朋友以及鄰居參加,視乎新郎或新娘及其家人的意願,小孩和大人可以分開坐也可以坐在一起,小孩亦可以與大人一起載歌載舞或是共同進餐聊天等。在婚禮當中,所有人都可以唱歌、送禮、許願、食大餐、跳舞、祝福新人等,另外也有一個認教父教母的儀式。

教育

阿爾巴尼亞實行9年制義務教育。地拉那大學是阿爾巴尼亞最好的綜合大學。

產業與生活

根據世界銀行數據2018年該國人均GDP為5319美元。阿爾巴尼亞曾經是歐洲最貧窮的國家之一,當時全國約一半的人口依然從事農業種植,但近年比例已明顯減少,大約只有15%左右,而且著重於旅遊業和其他第三產業發展。全國大約五分之一的人口在國外工作。國家面臨的經濟問題主要是較高的失業率,而國內整體失業率約10%至15%左右。雖然過去的阿爾巴尼亞一直依賴農業和重工業,但從事農業的人大多是在用過時的設備及方法來耕作,這阻礙了阿爾巴尼亞的經濟發展。

因為共產政權倒台後起初阿爾巴尼亞國內的貧窮、貪腐、內亂問題十分嚴重,所以阿爾巴尼亞政府在上世紀90年代曾接受了不少外國的經濟援助,而主要援助國包括中華人民共和國、希臘、意大利及土耳其。隨著國家經濟持續改善、旅遊業發展蓬勃、治安穩定起來,現時阿爾巴尼亞政府基本上已不再需要外國的經濟援助。

阿爾巴尼亞全國出口產物較少,主要出口肉類、工業原材料、天然資源等,而進口主要來自鄰國希臘和意大利。進口貨品的資金主要來自於經濟援助和在國外工作的阿爾巴尼亞人移民所帶回來的收入。希臘政府也通過非正式地向阿爾巴尼亞公民販賣希臘簽證。隨著國家在1990年代民主化後,阿爾巴尼亞公民亦開始有自由出入境和出國旅遊或經商等的權利,但為阿爾巴尼亞公民提供免簽證的國家仍不多。正因如此兩國在阿爾巴尼亞的主要城市都設有簽證機構,一度在阿爾巴尼亞公民自由出入歐盟國家的問題上經常發生非正面衝突,現時情況已逐步改善。

信仰與節日

大多數阿爾巴尼亞人是文化穆斯林(主要归入遜尼派,少數是什葉派,蘇非拜克塔什教团組成),也有少數人名義上是基督徒(天主教和東正教)。

阿爾巴尼亞人首先出現在11世紀末拜占庭人的歷史記錄中。[42]此時他們已經完全基督教化了。當時所有的阿爾巴尼亞人都是東正教的基督徒,直到13世紀中期,當時的盖格方言的人羣被轉變為天主教,以抵抗斯拉夫人。 [43][44][45]

而根據2011年人口普查,阿爾巴尼亞人58.79%信仰伊斯蘭教,是成為該國最大的宗教信仰。其中絕大多數阿爾巴尼亞穆斯林是世俗遜尼派,而少數的派別中,比較重要的是被稱爲拜克塔什的少數派。基督教佔了16.99%的人口,使其成為該國第二大宗教信仰。 [46] 蓋洛普“2010年全球報告”顯示,宗教在阿爾巴尼亞人中只有在39%的生活方面發揮作用,並將阿爾巴尼亞排在世界第十三最少的宗教國家。 [47]

第二次世界大戰後控制阿爾巴尼亞的共產黨政權迫害以及壓制宗教儀式和機構,完全禁止宗教,甚至宣布阿爾巴尼亞成為世界上第一個無神論國家。自1992年政權改變以來,阿爾巴尼亞獲得宗教自由。阿爾巴尼亞的穆斯林人口(主要是世俗遜尼派分支)遍及全國,而阿爾巴尼亞東正教的基督徒以及貝克塔什人則集中在南部; 羅馬天主教徒主要在該國北部。[48] 在部分歷史上,阿爾巴尼亞還有一個猶太社區。 在納粹佔領期間,一群阿族人拯救了猶太社區的成員。[49]

- 新年:1月1-2日

- 夏日:3月4日

- 內夫路斯節:3月22日

- 天主教復活節:3月或4月

- 正教會復活節:3月或4月

- 國際勞動節:5月1日

- 開齋節:伊斯蘭曆9月

- 特蕾莎修女節:10月19日

- 宰牲節(古爾邦節):伊斯蘭曆12月

- 獨立日:11月28日(1912年)

- 解放日:11月29日(1944年)

- 國家青年節:12月8日

- 聖誕節:12月25日

(如果節日碰巧與周六或周日在同一天,那麽將順延補休一天。)

| 宗教 | 阿爾巴尼亞 | 科索沃 | 阿爾巴尼亞人在馬其頓 | 阿爾巴尼亞人在蒙特內格羅 | 阿爾巴尼亞人在克羅地亞 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 人口 | % | 人口 | % | 人口 | % | 人口 | % | 人口 | % | |

| 伊斯蘭教 遜尼派 拜克塔什教团 | 1,646,236 1,587,608 58,628 | 58.79 56.70 2.09 | 1,663,412 — — | 95.60 — — | 502,075 — — | 98.62 — — | 22,267 — — | 73.15 — — | 9,594 — — | 54.78 — — |

| 基督徒 天主教 東正教 福音派 其他基督徒 | 475,629 280,921 188,992 3,797 1,919 | 16.99 10.03 6.75 0.14 0.07 | 64,275 38,438 25,837 — — | 3.69 2.20 1.48 — — | 7,008 7,008 — — — | 1.37 1.37 — — — | 8,027 7,954 37 — 36 | 26.37 26.13 0.12 — 0.12 | 7,126 7,109 2 — 15 | 40.69 40.59 0.01 — 0.09 |

| 無神論者 | 69,995 | 2.50 | 1,242 | 0.07 | — | — | 35 | 0.11 | 316 | 1.80 |

| 不想回答 | 386,024 | 13.79 | 9,708 | 0.55 | — | — | 58 | 0.19 | 414 | 2.36 |

| 無教派者 | 153,630 | 5.49 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 不相關/未說明 | 68,022 | 2.43 | 1,188 | 0.06 | — | — | 48 | 0.16 | 63 | 0.36 |

藝術與文學

文學

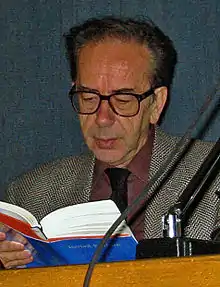

早期一些阿爾巴尼亞人撰寫的文學涉及宗教主題。[50] 現在知道的最早使用阿爾巴尼亞語的作品,是由杜魯斯保羅·安古爾斯大主教於1462年寫的洗禮式。 隨著許多阿族人皈依伊斯蘭教,伊斯蘭教的詩和其他文學傳統也逐漸被採納,諸如Bejtexhinj(阿爾巴尼亞詩人)等作家,以及像Nezim Frakulla,Hasan Zyko Kamberi,MuhametKyçyku和兄弟Shahin和DalipFrashëri這樣的人物。[51] 在他們編纂的阿爾巴尼亞文學中,很多的背景是來自中東地區的語言以及當地的社會文化環境。[51] 阿爾巴尼亞從1912年獨立到第二次世界大戰的到來的這段時間以來,從原本的愛國以及政治相關的作品轉變爲更具特色、具有成熟形式的散文和詩歌,以及著重於當代生活的其他主題的阿爾巴尼亞文學。 阿爾巴尼亞最著名的作家是凡·諾利()和伊斯梅爾·卡達萊()。

伊斯梅爾·卡達萊

伊斯梅爾·卡達萊

電影

阿爾巴尼亞革命電影曾經對毛澤東統治時期的中國大陸有過一定影響。影如《廣闊的地平線》、《寧死不屈》、《地下遊擊隊》、《第八個是銅像》、《戰鬥的早晨》、《勇敢的人們》、《腳印》、《伏擊戰》、《海岸風雷》、《在平凡的崗位上》等等,都是著名作品。

斯克拉巴里区的傳統男合唱小組

斯克拉巴里区的傳統男合唱小組

現況

近來歐洲難民問題一直未有得到妥善解決,大家可能以為源源不絕的難民多數來自戰亂或鬧飢荒國家,如敘利亞、利比亞等,但事實並非如此。 英國《每日郵報》報道,每八名申請難民資格的兒童中,便有一人來自巴爾幹半島國家,其中,阿爾巴尼亞的情況令人關注。 去年,共有3175名兒童在沒有成人陪同的情況下抵達英國尋求庇護,其中405人就是來自前共產國家阿爾巴尼亞。以接收難民數目計,英國在歐盟國家之中排第四。 去年,整個歐盟便接到32000宗阿爾巴尼亞人的難民申請,他們聲稱在國內受到迫害,原因五花八門,包括種族、宗教或性問題。

有人指,現時阿爾巴尼亞既沒有發生戰亂(1990年代的阿爾巴尼亞曾發生內戰和政局動盪),近年政局亦漸趨穩定,亦沒有天災,言論和宗教自由亦得到保障,但竟然有如此多的兒童(大多為青少年)孤身出走至西歐國家,情況並不尋常,促請當局重新審視難民制度,不應浪費納稅人金錢。

但亦有人認為,當局應憑良心及一貫道德標準行事,無論是甚麼原因,只要是真的受到迫害,便應為他提供保護。

出走的較大可能性是阿爾巴尼亞青少年希望到西歐國家尋找高收入工作。

參見条目

- 大阿爾巴尼亞

注釋

参考资料

- . [2012-03-30]. (原始内容存档于2018-12-24).

- (PDF). [2017-06-26]. (原始内容存档于2018-12-24).

- Ragionieri 2008,第46頁.

- . Todayszaman.com. 21 August 2011 [4 November 2015]. (原始内容存档于31 October 2015).

- Managing Migration: The Promise of Cooperation. By Philip L. Martin, Susan Forbes Martin, Patrick Weil

- [Graph 7 Resident population with foreign citizenship] (PDF). Greek National Statistics Agency. 23 August 2013 [3 June 2014]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2013-12-25).

- Groenendijk 2006,第416頁. "approximately 200,000 of these immigrants have been granted the status of homogeneis".

- (PDF). [24 December 2013]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2011-07-27).

- . Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. 2012-12.

- . [18 August 2010]. (原始内容存档于2010年8月11日) (罗马尼亚语).

- . [2017-06-26]. (原始内容存档于2019-08-08).

- . istat.it. [3 October 2014]. (原始内容存档于13 November 2014).

- Hans-Peter Bartels: Deutscher Bundestag – 16. Wahlperiode – 166. Sitzung. Berlin, Donnerstag, den 5. Juni 2008 的存檔,存档日期3 January 2013.

- (PDF). [22 September 2010]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2011年7月7日).

- . Infowilplus.ch. 2007-05-25 [22 September 2010]. (原始内容存档于2012-12-10).

- . [2017-06-26]. (原始内容存档于2019-01-07).

- Bennetto, Jason. . London: Independent.co.uk. 2002-11-25 [22 September 2010]. (原始内容存档于2015-09-25).

- . Statistik.at. [24 December 2013]. (原始内容存档于2010年11月13日).

- . Insee.fr. [4 November 2015]. (原始内容存档于2015-12-09) (法语).

- . Dst.dk. [22 September 2010]. (原始内容存档于26 September 2010).

- .

- . [12 January 2012]. (原始内容存档于2011年12月22日) (法语).

- . cafebabel.com. [12 January 2012]. (原始内容存档于2011-12-26).

- Olson, James S., An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires. (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1994) p. 28–29

- . United States Census Bureau. [30 November 2012]. (原始内容存档于2014-10-06).

- . [2017-06-26]. (原始内容存档于2013-12-20).

- (Microsoft Excel download). 2006 Census. Australian Bureau of Statistics. [2 June 2008]. (原始内容存档于2019-01-06). Total responses: 25,451,383 for total count of persons: 19,855,288.

- (PDF). [2016-07-09]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2016-09-16).

- . The World Factbook. CIA. [1 September 2009]. (原始内容存档于2010年7月23日).

- Simon Broughton; Mark Ellingham; Richard Trillo. . Rough Guides. 1999: 5 [13 July 2013]. ISBN 978-1-85828-635-8. (原始内容存档于2020-04-30).

Most of the ethnic Albanians that live outside the country are Ghegs, although there is a small Tosk population clustered around the shores of lakes Presp and Ohrid in the south of Macedonia.

- (PDF). [2012-03-30]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2010-09-22).

- Nasse 1964,第24–26頁.

- Geniş & Maynard 2009,第553–555頁. "Taking a chronological perspective, the ethnic Albanians currently living in Turkey today could be categorized into three groups: Ottoman Albanians, Balkan Albanians, and twentieth century Albanians. The first category comprises descendants of Albanians who relocated to the Marmara and Aegean regions as part of the Ottoman Empire's administrative structure. Official Ottoman documents record the existence of Albanians living in and around Istanbul (Constantinople), Iznik (Nicaea), and Izmir (Smyrna). For example, between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries Albanian boys were brought to Istanbul and housed in Topkapı Palace as part of the devşirme system (an early Ottoman practice of human tribute required of Christian citizens) to serve as civil servants and Janissaries. In the 1600s Albanian seasonal workers were employed by these Albanian Janissaries in and around Istanbul and Iznik, and in 1860 Kayserili Ahmet, the governor of Izmir, employed Albanians to fight the raiding Zeybeks. Today, the descendants of Ottoman Albanians do not form a community per se, but at least some still identify as ethnically Albanian. However, it is unknown how many, if any, of these Ottoman Albanians retain Albanian language skills. The second category of ethnic Albanians living in modern Turkey is composed of people who are the descendants of refugees from the Balkans who because of war were forced to migrate inwards towards Eastern Thrace and Anatolia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as the Ottoman Empire dissolved. These Balkan Albanians are the largest group of ethnic Albanians living in Turkey today, and can be subcategorized into those who ended up in actual Albanian-speaking communities and those who were relocated into villages where they were the only Albanian-speaking migrants. Not surprisingly, the language is retained by some of the descendants from those of the former, but not those of the latter. The third category of ethnic Albanians in Turkey comprises recent or twentieth century migrants from the Balkans. These recent migrants can be subcategorized into those who came from Kosovo in the 1950s–1970s, those who came from Kosovo in 1999, and those who came from the Republic of Albania after 1992. All of these in the third category know a variety of modern Albanian and are mostly located in the western parts of Turkey in large metropolitan areas. Our research focuses on the history of migration and community formation of the Albanians located in the Samsun Province in the Black Sea region around 1912–1913 who would fall into the second category discussed above (see Figure 1). Turkish census data between 1927 and 1965 recorded the presence of Albanian speakers in Samsun Province, and the fieldwork we have been conducting in Samsun since September 2005 has revealed that there is still a significant number of Albanians living in the city and its surrounding region. According to the community leaders we interviewed, there are about 30,000–40,000 ethnic Albanian Turkish citizens in Samsun Province. The community was largely rural, located in the villages and engaged in agricultural activities until the 1970s. After this time, gradual migration to urban areas, particularly smaller towns and nearby cities has been observed. Long-distance rural-to-urban migration also began in later years mostly due to increasing demand for education and better jobs. Those who migrated to areas outside of Samsun Province generally preferred the cities located in the west of Turkey, particularly metropolitan areas such as Istanbul, Izmir and Bursa mainly because of the job opportunities as well as the large Albanian communities already residing in these cities. Today, the size of the Albanian community in Samsun Province is considered to be much smaller and gradually shrinking because of outward migration. Our observation is that the Albanians in Samsun seem to be fully integrated into Turkish society, and engaged in agriculture and small trading businesses. As education becomes accessible to the wider society and modernization accelerates transportation and hence communication of urban values, younger generations have also started to acquire professional occupations. Whilst a significant number of people still speak Albanian fluently as the language in the family, they have a perfect command of the Turkish language and cannot be distinguished from the rest of the population in terms of occupation, education, dress and traditions. In this article, we are interested in the history of this Albanian community in Samsun. Given the lack of any research on the Albanian presence in Turkey, our questions are simple and exploratory. When and where did these people come from? How and why did they choose Samsun as a site of resettlement? How did the socio- cultural characteristics of this community change over time? It is generally believed that the Albanians in Samsun Province are the descendants of the migrants and refugees from Kosovo who arrived in Turkey during the wars of 1912–13. Based on our research in Samsun Province, we argue that this information is partial and misleading. The interviews we conducted with the Albanian families and community leaders in the region and the review of Ottoman history show that part of the Albanian community in Samsun was founded through three stages of successive migrations. The first migration involved the forced removal of Muslim Albanians from the Sancak of Nish in 1878; the second migration occurred when these migrants’ children fled from the massacres in Kosovo in 1912–13 to Anatolia; and the third migration took place between 1913 and 1924 from the scattered villages in Central Anatolia where they were originally placed to the Samsun area in the Black Sea Region. Thus, the Albanian community founded in the 1920s in Samsun was in many ways a reassembling of the demolished Muslim Albanian community of Nish. This trajectory of the Albanian community of Nish shows that the fate of this community was intimately bound up with the fate of the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans and the socio-cultural composition of modern Turkey still carries on the legacy of its historical ancestor."

- Milliyet, Türkiyedeki Kürtlerin Sayısı. 2008-06-06.

- name="Zamanheritage">"Albanians in Turkey celebrate their cultural heritage 的存檔,存档日期31 October 2015.". Today's Zaman. 21 August 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- Cuneyt Yenigun. (PDF). Süleyman Demirel University:Faculty of Arts and Sciences Journal of Social Sciences. [4 November 2015]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于27 September 2015).

- Elsie 2010,第125–126頁. "With the advent of Gamal Abdel Nasser and the Arab nationalization of Egypt, not only the royal family but also the entire Albanian community- some 4,000 families- were forced to leave the country, thus bringing the chapter of Albanians on the Nile to a swift close".

- Norris 1993,第209–210頁; 244–245.

- Elsie 2003,第3頁.

- Licursi, Emiddio Pietro (2011). Empire of Nations: The Consolidation of Albanian and Turkish National Identities in theLate Ottoman Empire, 1878–1913. New York: Columbia University. p. 19.

- Raymond Zickel; Walter R. Iwaskiw (编). . 1994 [9 April 2008]. (原始内容存档于2017年3月26日).

- Comnena, Anna. The Alexiad, Book IV.

- Stavrianos 2000,第498頁. "Religious differences also existed before the coming of the Turks. Originally, all Albanians had belonged to the Eastern Orthodox Church... Then the Ghegs in the North adopted in order to better resist the pressure of Orthodox Serbs."

- Hugh Chisholm. . Encyclopædia Britannica. 1910: 485 [18 July 2013]. (原始内容存档于2020-04-30).

The Roman Catholic Ghegs appear to liave abandoned the Eastern for the Western Church in the middle of the 13th century

- Ramet 1989,第381頁. "Prior to the Turkish conquest, the ghegs (the chief tribal group in northern Albania) had found in Roman Catholicism a means of resisting the Slavs, and though Albanian Orthodoxy remained important among the tosks (the chief tribal group in southern Albania), ..."

- 2011 Albanian Census 的存檔,存档日期2017-03-26.

- . Gallup.com. [25 March 2013]. (原始内容存档于2012-09-27).

- . State.gov. 14 September 2007 [27 August 2010]. (原始内容存档于2010-08-28).

- Sarner 1997.

- Elsie 2005,第4頁.

- Elsie 2005,第36–43頁.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)