| Álvaro de Zúñiga y Guzmán | |

|---|---|

| |

.svg.png.webp) Coat of arms of the Duchy of Béjar | |

| Reign | |

| Born | 1410 |

| Died | 10 June 1488 (aged 78) Béjar |

| Spouse |

|

| Father | Pedro de Zúñiga y Leiva |

| Mother | Isabel Elvira de Guzmán y Ayala |

Álvaro de Zúñiga y Guzmán[note 1] (Encinas de Esgueva, 1410 - Béjar, 10 June 1488) was a Castilian nobleman, member of the influential House of Zúñiga, of Navarrese origin. He was one of the most powerful men in Castile, as evidenced by his numerous titles and the offices he held, and was involved in much of the kingdom's most important political and military events, notably in the various conflicts between the nobility and the candidates for succession to the throne that would culminate in the War of the Castilian Succession and that would only calm down with the final recognition of the Catholic Monarchs, whom he initially opposed but eventually supported.

As a maid to King John II of Castile, in his youth he fought alongside his father against Álvaro de Luna, Constable of Castile and Favourite of King John. When his father died in 1453, he became the second Count of Plasencia and leader of the Liga Nobiliaria. He supported King Henry IV during the first years of his reign, but eventually fell out with the king for opposing the rights of succession of his daughter, Joanna la Beltraneja, and supporting the claims to succession of Alfonso, Prince of Asturias, Henry's half-brother.

Álvaro de Zuñiga becomes the leader of the Liga Nobiliaria, the party created to defend Alfonso's rights to the throne, which is hosted in Zuñiga's palace in Plasencia, which functions as a court of the future king. Álvaro de Zuñiga is one of the main characters in the so-called Farce of Ávila, a ceremony that took place on 5 June 1465, during which the deposition of Henry IV was staged and D. Alfonso was acclaimed king. This marked the beginning of the War of the Castilian Succession. In 1467, Álvaro de Zuñiga formally reconciled with Henry IV and approached the Portuguese King Afonso V, who was received by Zuñiga in Plasencia in May 1475 where he married Joanna, who had been the acclaimed queen of Castile the previous year.

After the defeat of the Portuguese king against the armies of the Catholic Monarchs at the Battle of Toro (1 March 1476), Álvaro de Zuñiga becomes neutral in the civil war and the Catholic Monarchs eventually recognize most of Álvaro's titles and possessions, later granting him more privileges.

Biography

Affiliation

Álvaro de Zúñiga was the son of Pedro de Zúñiga y Leiva and his wife Isabel Elvira de Guzmán y Ayala. His father was justicia mayor and alguacil mayor of Castile, 1st Count of Ledesma. His mother was Senhora de Gibraleón and daughter of Alvar Pérez de Guzmán and his wife Elvira de Ayala

In 1429 Álvaro married Leonor Manrique de Lara y Castilla, daughter of Pedro Manrique de Lara, Lord of Amusco, adelantado mayor of León and his wife Leonor de Castilla. The marriage was concerted in January 1428 by the parents of the bride and groom, to unite the two powerful families. The couple had nine children:[1]

- Pedro (1430-1484), 2nd Count of Bañares, 1st of Ayamonte;

- Diego, Prior of San Marcos in León in the Order of Santiago;

- Álvaro, Prior of Saint John of Jerusalem (later Order of Malta);

- Iñigo, who died very early;

- Francisco, Lord of Mirabel and Berantevilla;

- Fadrique, Bishop of Osma;

- Leonor, married to Juan de Luna y Pimentel, 2nd Count of San Esteban de Gormaz and widow of Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 4th Lord of Oropesa;

- Elvira (1430-?), married to Alonso de Sotomayor y Guzmán, 1st Count of Belalcázar;

- Joan, Abbess in the monastery of Calabecinos.

After becoming a widower, Álvaro married in 1458 his niece, Leonor Pimentel y Zúñiga, daughter of Juan Alonso Pimentel (Count of Mayorga), and his sister, Elvira de Zúñiga y Guzmán. In order to achieve this, she obtained a papal exemption from Pius II and King Henry IV.[2]From her second marriage she had four children:

- Juan de Zúñiga y Pimentel, Master of the Order of Alcántara,[3] archbishop of Seville, Primate of Spain and 2nd Duke of Plasencia;

- Fernando, Prior;

- Maria (1465-?), Lady of Burguillos, married to her nephew Álvaro II de Zúñiga y Guzmán, 2nd Duke of Béjar, Count of Bañares and Marquis of Gibraleón;

- Isabel (1470-1520), married to Faldrique Álvarez de Toledo, firstborn of the 1st Duke of Alba de Tormes, Garcí Álvarez de Toledo and his wife María Enríquez.[4]

The Duchess Leonor Pimentel died in Béjar on 31 March 1486.[5]

At the service of John II

As a child, Álvaro de Zúñiga y Guzmán was the donzel of John II of Castille. In his youth, he collaborated with his father in the fight against Álvaro de Luna, Constable of Castile and Favourite of John, over whom he had great influence. On 22 May 1430 Álvaro was named king and appointed Álvaro alguacil mayor of Castile.[6]

On 9 September 1433 Álvaro and his father Pedro joined the Velascos to fight for John II's effective freedom. In February 1437 Álvaro de Luna ordered the arrest of the adelantado Pedro Manrique de Lara, who had held the second post in the royal council since 1430. Pedro Manrique de Lara was arrested on 13 August 1437, but escaped on the night of 20-21 August with the help of Álvaro de Zúñiga.[7]

The Favourite Álvaro de Luna ignited the rivalry of the House of Zúñiga with the Álvarez de Toledo by granting the county of Alba de Tormes to Hernán Álvarez de Toledo, which gave rise to an entrenched struggle for control of Salamanca.[8] Some cities, such as Cáceres and Trujillo, opposed armed resistance to attempts to convert them from realengo (royal jurisdiction) to landlords. Trujillo was offered to Pedro de Zúñiga in exchange for Ledesma. With Béjar and Plasencia in their possession, from 1440 onwards, the House of Zúñiga directed its policy towards definitively controlling Extremadura.[9]

Álvaro, his father, Pedro Manrique, and the 2nd Admiral of Castile, Fadrique Enriquez, prepared the rebellion of the league of the nobility against the Favourite Álvaro de Luna. This league, composed of Pedro de Castilla, Bishop of Osma, Sancho de Rojas, bishop of Astorga, Luis de la Cerda, Count of Medellín, among others, committed themselves on 19 June 1439 to accept the mediation of the King of Navarre, John II, and the infante Henry, so that the disturbances in the kingdom would cease.[10] On 21 September a confederation pact is signed by Pedro de Zúñiga, his son Álvaro, the Count of Haro, and his son Pedro Fernández de Velasco, to free King John II of Castile from the oppression he was in, promising him help until he saw the king free and the kingdom appeased.[11] On 1 December 1450 Pedro de Zúñiga renounced the title of alcalde of Seville in favor of his son Álvaro.[12]

In early 1543 King John II, instigated by the queen, was willing to eliminate his favourite through his King of Arms, Diego López de Zúñiga y Navarra, lord of Clavijo, a relative of the count of Plasencia. The queen obtained a document from the king legalizing the rebellion of the count of Plasencia and authorizing the arrest of Álvaro de Luna. Pedro de Zúñiga, the Count of Plasencia, causes his son Álvaro to settle with his troops in Curiel de Duero before 30 July 1453. The Favourite Álvaro de Luna wanted to prevent the movement by taking possession of Béjar, where Pedro had fortified himself but failed in his attempt because one of his loyalists, Alonso Pérez de Vivero, communicated the favourite's plans to the count of Plasencia. The valid had Alonso Pérez de Vivero murdered in Burgos on 1 April 1453.[13]

Álvaro de Zúñiga is called to Burgos on behalf of the king. On the night of 1-2 April Álvaro de Zúñiga and his soldiers enter the castle of Burgos. King John II, tortured by doubts and vacillations, sent him four letters written by his own hand, the last one on 3 April and the following dispatch on 4 April: "Don Álvaro de Stunica, my alguacil-mor: I command you to arrest the body of Don Álvaro de Luna, Master of Santiago and, if he defends himself, to kill him."[14]

At dawn on 4 April Álvaro de Zúñiga came down from the castle with the dispatch in a gauntlet and went to Pedro de Cartagena's house, where Álvaro de Luna was staying. His servants defended themselves with arrows for three hours, after which they surrendered along with the favourite. Álvaro de Luna was imprisoned in the fortress of Portillo, under the custody of Diego López de Zúñiga y Navarra. The king assigned ten jurists to the trial of the favourite. The judges agreed on the death penalty, but that it should be carried out by warrant and not by sentence. The execution order was received in Portillo on 31 May 1453. Álvaro de Luna was taken to Valladolid the next day, where he spent the night in one of the houses of Count Plasencia, Pedro de Zúñiga, in the old street of Francos. Álvaro de Luna retained serenity on the way to the scaffold. He was beheaded in the Plaza Mayor of Valladolid on 3 June 1453.[15] The Zúñiga replaced Álvaro de Luna in the privacy and royal favor of John II.[16]

When his father died in July 1453, Álvaro de Zúñiga took possession of Plasencia by deed of 15 August 1453 and became 2nd Count of Plasencia. He took over leadership of the Liga Nobiliaria and inherited the positions of justicia-mor and alguacil-mor of Castile. Zuñiga also became the 2nd Count of Plasencia.[17]

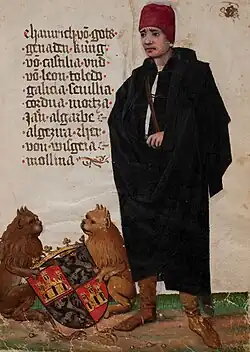

At the service of King Henry IV of Castile and León

King John II died in Valladolid on 21 July 1454. The Prince of Asturias was proclaimed King of Castile and León as Henry IV in Valladolid on 23 July 1454. His reign began with the agreement of the nobles. His first Favourite was Juan Pacheco, 1st Marquis of Vilhena, who had been educated and raised in the royal palace and was the new king's companion from childhood. Henry IV had married Blanche II of Navarre in 1440, daughter of King John II of Aragon but the marriage was annulled by Pope Nicholas V on 27 July 1453 for not being consummated, due to Henry's impotence and acknowledged homosexuality. This episode earned Henry the epithet "the Impotent." Henry remarried on 20 May 1455 to Princess Joan of Portugal, sister of King Alfonso V of Portugal.[18]

Henry IV decided to continue the war with Granada and thus entertain the nobility in their restless bellicosity. Álvaro de Zúñiga and his host of Plasencia arrived, and the incursions lasted several years. In the summer of 1458, Queen Joan and her ladies participate in the military operations as spectators at a party.[19] After the conferences of Alfaro between kings Henry of Castile and León and John of Navarre and Aragon, in May 1457, the Favourite Juan Pacheco, benefiting from the agreements, reduces the Liga Nobiliaria to impotence, enthroning its most prominent members in the new government: the Master of the Order of Calatrava Pedro Girón, the Accountant Diego Arias, the Archbishop of Seville Alonso de Fonseca y Ulloa, the Count of Plasencia Álvaro de Zúñiga and the Count of Alba Hernán Álvarez de Toledo. Beltrán de la Cueva is appointed Constable of Castile on 25 March 1458.[20]

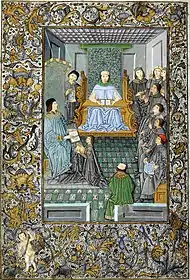

The relations of Álvaro de Zúñiga, Count of Plasencia, with King Henry IV and with the Favourite Juan Pacheco, Marquis of Vilhena, were very cordial and firm between 1458 and 1464. After the death of his first wife, Leonor Manrique of Lara and Castile, Álvaro wished to marry his goddaughter and niece Leonor Pimentel y Zúñiga, despite the consanguinity and age difference (he was 49 and she was 16). Pope Callixtus III refused to grant the necessary exemption, but his successor, Pope Pius II, issued the license that allowed the consanguineous marriage.[2] Henry IV also authorized the marriage and declared on 18 March 1461 that it had taken place by his order.[21][22][23]

Liga Nobiliaria

The leading members of the aristocracy, including the count of Plasencia, met in Alcalá de Henares and created a league for the "Good of the Kingdom" and "Recognition of Alfonso, Prince of Asturias", Henry's half-brother, as "Prince of Asturias and successor". King John II of Navarre joined the league on 1 April 1460.[24] For services rendered, Prince Alfonso grants Álvaro de Zúñiga the village of Trujillo and Cáceres on 13 April 1460.[6] The members of the league, meeting in Yépez in February 1461, drafted a political program with four points, among which were respect for the privileges of the nobles and the oath of Alfonso as Prince of Asturias and heir to the throne of Castile. On 26 August 1461 Henry IV signed an agreement with the league that satisfied the nobility, as it met their wishes for the maintenance of the oligarchy and the institution of a government run by a team of nobles.[25]

On 28 February 1462 Queen Joan gave birth to Joanna, who would become known as "la Beltraneja." Her baptismal godmother was Princess Isabella, the future Queen Isabella I of Castile, sister of Alfonso, and half-sister of Henry. The courts assembled on 9 May 1462, and took the customary oath to the newborn infanta Joanna. On 20 May 1462 King Henry IV announced to the kingdom that in the absence of male children, Joanna would be his heir.[26] Beltrán de La Cueva had been appointed a member of the king's council on 20 May 1462. In early 1464, Henry appointed him his favourite.[27] Álvaro de Zúñiga, Henrique de Guzmán, Duke of Medina Sidonia, Rodrigo Ponce de León, Count of Arcos, and other noble knights participated with their hosts in the conquest of Gibraltar, which fell on 16 August 1462.[28] Beltrán de la Cueva was also a member of the king's council.

Conflict between the nobility and the Crown

In April 1464, King Henry IV meets with the King of Portugal Afonso V and agrees to the marriage of his half-sister Isabella to the Portuguese king.[29] Rumors circulate about the infanta Joanna being fruit of Queen Joan's adultery with the king's butler and valet, Beltrán de La Cueva,[30] which is the origin of the princess' nickname ("la Beltraneja").[31]

The Liga Nobiliaria was composed of Álvaro de Zúñiga, Count of Plasencia, Fadrique Enríquez, Admiral of Castile and Count of Trastámara, Rodrigo Pimentel, Count of Benavente, and Garcí Álvarez de Toledo, Count of Alba, formed on 16 May 1464, pledging to defend the rights of infante Alfonso and prevent infanta Isabella from marrying without the league's consent. King Henry responds to this move by granting the title of Master of the Order of Santiago to Beltrán de La Cueva on 24 May 1464. The Marquis of Vilhena, Juan Pacheco, sends royal troops to arrest the Archbishop of Seville, Alonso de Fonseca, who seeks refuge in the castle of Béjar, owned by the count of Plasencia. This act provoked the open rebellion of the House of Zúñiga. Álvaro de Zúñiga breaks the agreed truce and mobilizes his troops to help the archbishop, which forces the lifting of the siege ordered by Henry IV on the Fonseca estates of Coca and Alaejos.[32]

The Liga Nobiliaria presided over by Álvaro de Zúñiga sent emissaries to Pope Paul II in the summer of 1464 to prevent the appointment of Beltrán de La Cueva as master of Santiago, but the pope decided to accede to the king's wishes and issued a bull confirming Beltrán as Master of the order.[33]The counts of Plasencia and Alba, the marquis of Vilhena, and the Manrique de Lara prepared an interview with King Henry to imprison the king near Segovia, between San Pedro de las Dueñas and Villacastín. On 15 September 1464 the king received news from a messenger of the proximity of the nobles' troops, which were 30 km from Segovia. The peasants of the neighboring villages rushed to defend the king and the league was disconcerted by this failure.[34]

The marquis of Vilhena held a magna assembly in Burgos between 26 and 28 September 1464. It was attended by Álvaro de Zúñiga and his brother Diego López de Zúñiga, Count of Miranda, as well as the canon of the cathedral and the municipality. The estates of the realm (social classes) of the kingdom were represented. The manifesto of the assembly of Burgos called for the removal of Beltrán de la Cueva, stated that Joanna was not the daughter of Henry, and demanded that Prince Alfonso be recognized as the successor, that he be given the title of master of the Order of Santiago, and that he be raised in the house of the counts of Plasencia. In his pact with the league, Henry IV agreed to recognize his half-brother Alfonso as his successor on the condition that he married Joanna. Beltrán de La Cueva renounced the title of Master of Santiago in favor of the infante Alfonso on 29 October 1464.[35]

At the conference with King Henry that took place between Cigales and Cabezón on 4 December 1464, infante Alfonso, then 14 years old, was sworn in as successor by the nobles present, and a reform commission was appointed consisting of two representatives of the king, Pedro de Velasco and Gonzalo de Saavedra, two representatives of the nobility, the count of Plasencia and the marquis of Vilhena, and a mediator, Friar Alonso de Oropesa. The terms of the agreement were signed on 30 November 1464.[36] The reform commission drafted a petition with 39 chapters and decreed the banishment of Beltrán de La Cueva and his supporters on 12 December 1464.[37] According to the petition, an authentic Magna Carta, the nobility was granted a habeas corpus - from then on, only with the authorization of a commission composed of the Marquis of Vilhena, the counts of Haro and Plasencia, the archbishops of Toledo and Seville, and the prosecutors of Toledo, Seville, and Burgos, could the king order the arrest of a noble.[38] However, Henry IV annuls the agreement of Cigales in February 1465 and forbids the recognition of the infante Alfonso as his heir to the crown of Castile.

Aclamation of Alfonso XII as King of Castile and León

Álvaro de Zúñiga's palace in Plasencia became the court of the future king Alfonso, Prince of Asturias. The marquis of Vilhena also settled in Plasencia, a city that became the headquarters of the rebels.[39]

Henry IV sends an ultimatum to the Liga from Salamanca in April 1465 demanding the return of Prince Alfonso. On 10 May 1465 the counts of Plasencia and Benavente and the master of Alcántara responded on behalf of the league, demanding compliance with the agreements of Cigales, threatening to renounce obedience to the king if the agreements were not fulfilled. Infante Alfonso is the acclaimed King of Castile and León at Valladolid as Alfonso XII by Fadrique Enriquez. On 5 June 1465 a symbolic dethronement of Henry IV is staged, which would become known as the Farce of Ávila. The nobles gather in the city outside the walls, and place on a wooden platform a dummy dressed in mourning, with a crown, cloak, sword, and scepter, representing Henry IV. In front of the "sovereign," the nobles read a long list of his tremendous crimes. The archbishop of Toledo, Carrillo, takes away his crown, the count of Plasencia takes away his sword, the count of Benavente takes away his scepter, and the count of Miranda knocks the dummy down with kicks, accompanying the gesture with rude words. Then, in the same place, Alfonso XII was proclaimed king. The young men Juan de Zúñiga y Pimentel and Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba served as pages. Accompanied by the other nobles, Álvaro de Zúñiga takes his new king to Valladolid.[40]

At this time Álvaro de Zúñiga had in his power the semicircle formed by the cities from Ávila to Cáceres, and Diego López de Zúñiga had in his power Osma. Álvaro de Zúñiga sent his firstborn Pedro with letters to Juan Ponce de León, Count of Arcos, where for the first time the paternity of the infanta Joanna was attributed to Beltrán de la Cueva. The Alcázar of Seville and all of Andalusia sided with the rebellious nobles.[41] The third son of the count of Plasencia, Álvaro, was appointed before the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem (later the Order of Malta) for his services to King Alfonso XII.[42] Between Pedro de Zúñiga, Juan Ponce de León, and Juan Alonso de Guzmán, Duke of Medina Sidonia, a rivalry grew. Bloody riots, that lasted from 24 July to 11 August 1465, broke out in Seville between "new" and "old" Christians. Álvaro de Zúñiga and Pedro Girón, the master of Alcántara, headed to the city with their troops. At the end of November, the Zúñiga manage to get the count of Arcos, the duke of Medina Sidonia, and the Sevillian municipality to solemnly swear allegiance to Alfonso XII. Diego López de Zúñiga is appointed Corregedor of Seville, but the city managed to impose its conditions and eventually prevented him from taking office.[43]

The Civil War of 1465-1474

In the winter of 1465/66, the civil war degenerated into complete anarchy. In August 1466, the moderate rebel nobles decided to reconstitute the old league and bring together the count of Plasencia and the duke of Medina Sidonia, who had recently become estranged.[44] Through the Archbishop of Seville, Alfonso de Fonseca, a reconciliation meeting was arranged between King Henry IV and Álvaro de Zúñiga in Béjar in May 1467. The meeting did not take place because the people of Madrid thought it was a trap and, out of fear for their king, mutinied and did not let him leave the city.[45]

Alvaro de Zúñiga decided to accept the peace plan of the archbishop of Seville at the end of 1467 and offers his palace as a safe asylum for the king. Henry IV arrives in Plasencia on 28 December 1467, being welcomed by Álvaro de Zúñiga, and enjoys his support and hospitality for four months, promising to offer the village of Trujillo to the count.[46] In January 1468 the count of Plasencia is unable to take possession of Trujillo due to the opposition of its inhabitants. The count's reconciliation with the king caused division among the nobles. From April 1468 the count of Plasencia, the archbishop of Seville and Pedro González de Mendoza became part of the king's council.[47]

Meanwhile, the civil war in Castile continued until 1474, due to the king's indecisions regarding his succession. The infante declared king by the rebels, Alfonso XII, died on 5 June 1468.[47] On 19 September 1468 the Treaty of the Bulls of Guisando was signed, in which Henry IV declared princess Isabella, his half-sister, to be his legitimate successor. It was determined that Isabella's marriage needed prior authorization from the king and the advice of the marquis of Vilhena, the archbishop of Seville, and Álvaro de Zúñiga. Infantes Alfonso and Isabella were the children of the second marriage of King John II of Castile to Princess Isabella of Portugal, cousin of the Portuguese King Afonso V and his sister and Henry's wife, Joanna. The latter did not recognize the infanta Isabella as her successor and protested in Buitrago on 24 October 1468.[48] On 30 April 1469 the marriage of the infanta Isabella was agreed upon between Henry IV and John II of Portugal.[49] In a letter of 2 May 1469 the Portuguese king offered the expansion of the houses of Zúñiga, Fonseca, Pacheco, Velasco, and Mendoza in return for fidelity, political and military support.[50]

On 19 October 1469 Isabella marries in Valladolid, without royal consent, Prince Ferdinand, King of Sicily and successor to the throne of Aragon, who undertakes to assist his wife in her succession rights.[51]

King Henry IV harassed Trujillo, but the city refused to be incorporated into the lordship of the count of Plasencia. In compensation, on 2 November 1469, the king granted the count of the village and valley of Arévalo, which belonged to Isabella's mother.[52] Álvaro de Zúñiga took possession of Arévalo on 7 November 1469, and on 20 December that year he received the title duke of Arévalo.[53]

Henry IV reinstituted his daughter Joanna as his legitimate successor on 26 July 1470, and on 26 July 1470, the infanta Joanna was promised in marriage to the duke of Guyenne, brother of King Louis XI of France, who undertook to support Joanna's succession rights. The duke of Guyenne died on 25 May 1472.[54]

In the summer of 1470, Henry IV confirmed the title of duke of Arévalo and granted an annual income to Álvaro de Zúñiga in return for Trujillo not being incorporated.[55] At the time it was said, "It has always been the norm of the Trastámaras to make a gold run before the sword, to corrupt before wounding." The duke of Arévalo extended his influence in Extremadura, placing relatives in key places. He supports the clavero of the Order of Alcántara, Alonso de Monroy, in the latter's uprising against the order's Master, Gómez de Solís, and manages to get the pope to issue a papal bull appointing his son João as Master of that order. Another of his sons, Álvaro, obtains the priory of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, but since the Marquis of Vilhena, Master of the Order of Santiago and Favourite of Henry IV, had domains bordering the priory, Álvaro de Zúñiga undertook not to help his son, which contributed to his taking the side of Princess Isabella.[56]

Álvaro de Zúñiga took part in the meeting between the king of Castile and León, Henrique, and Afonso V of Portugal, which took place in May 1472 on the Caia river, between Badajoz and Elvas. The meeting had the purpose of a peace treaty that did not materialize. In the summer of 1472 the Liga Nobiliaria, now supporting King Henry, had among its members Juan Pacheco, Marquis of Vilhena, and the Duke of Arévalo.[57] Juan Pacheco agrees with Álvaro de Zúñiga to recognize the latter's son, Juan de Zúñiga y Pimentel, as master of the Order of Alcántara, in exchange for the renunciation of the duke of Arévalo's rights over the lordship of Trujillo in favor of the marquis of Vilhena.[58]

King Henry IV died in Madrid on 11 December 1474, leaving instructions to his testamentary (the Primate of Spain, Pedro González de Mendoza, the marquis of Vilhena, Diego López Pacheco, Diego Hurtado de Mendoza, the constable of Castile, Pedro Fernández de Velasco, Álvaro de Zúñiga y Guzmán and the count of Benavente) "that Princess Joanna, his daughter, should do what they agreed she should do". Only two of the testamentary trustees, Álvaro de Zúñiga and Diego López Pacheco, recognized Joanna as their successor - the first for his word and for fear of reprisals over the village of Arévalo, which had belonged to the mother of Princess Isabella; the second because he feared that the infantes of Aragon would claim the fiefs he had from them. Both advocated a system where the nobles predominated.[59]

The House of Zúñiga had heavily armed possessions in Béjar, Plasencia, Peñaranda de Duero, Arévalo, and Burgos, making them omnipotent in this area.[60] One of the sons of the Duke of Arévalo, Álvaro de Zúñiga y Manrique de Lara, before the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, was in the service of the Catholic Monarchs because he blamed his stepmother (Leonor de Pimentel y Zúñiga) for his father's rebellious attitude, and for the plea in favor of granting the title of master of Alcántara to his son Juan de Zúñiga y Pimentel (Álvaro's half-brother). On 20 February 1472 Pope Sixtus IV granted the degree of master of Alcántara to Juan de Zúñiga y Pimentel, then 13 years old.[3] The investiture ceremony took place on 23 January 1475 in the Church of Santa Maria de Almocóvar in Alcántara, swearing in Juan as master and his father Álvaro, Duke of Arévalo, as administrator and governor-general of the Order of Alcántara. While Juan was a minor, his father, duke of Arévalo, replaced him as the head of the Order of Alcántara.[61]

War of the Castilian Succession

Princess Isabella, daughter of King John II of Castile and León, and his second wife, Isabella, Princess of Portugal, was the acclaimed queen of Castile and León in Segovia on 13 December 1474. The duke of Arévalo and the marquis of Vilhena took Princess Joanna from Madrid to Trujillo, where she was proclaimed as the legitimate successor of Henry IV in March 1475. The Portuguese King Afonso V decides to marry Joanna, then 13 years old, and claims the crown of Castile for himself. The Catholic Monarchs were celebrating a great tournament in Valladolid with the presence of the high nobility when, on 3 April 1475, they received a message from the king of Portugal, that was in reality a declaration of war.

Afonso V entered Castile with his army in early May 1475 and was received in Plasencia by, among others, the Duke of Arévalo and count of Plasencia, Álvaro de Zúñiga, his brother Diego López de Zúñiga, Count of Miranda, Juan Téllez Girón, Count of Ureña, and Pedro Portocarrero, son of the marquis of Vilhena. Afonso and Joanna were proclaimed monarchs of Castile and León in Plasencia on 25 May 1475, and were married in the same city on 30 May that year.[62] In a royal decree of 24 May, Isabella ordered that Álvaro de Zúñiga, Juan Pacheco, Rodrigo Girón, and Juan Téllez Girón were not to be obeyed or held as lords of their villages for having incurred a crime of Lèse-majesté.[63] On 10 June 1475 Isabella ordered the sequestration of the goods of the duke of Arévalo for having taken the side of the king of Portugal.[64]

King Afonso V and his army took Arévalo, where the Portuguese king wasted time analyzing the war plans. He decided to go to Toro and not to Burgos, as the duke of Arévalo asked him to support his cousin Iñigo de Zúñiga y Avellaneda, alcalde of the castle-fortress of Burgos, belonging to the House of Zúñiga.[65] Álvaro de Zúñiga, Duke of Arévalo, won the battle of Batanás with the support of Afonso V on 18 September 1475. After this battle, the Portuguese army returns to Arévalo.[66] In October 1475 the Portuguese king and his army retreated to Zamora, where they set up their winter headquarters, ignoring the Zúñiga troubles in Burgos.[67] The castle of Burgos resisted for four months to the siege commanded by Afonso de Aragón but the alcalde Iñigo de Zúñiga y Avellaneda eventually surrendered on 28 January 1476, delivering the castle to Queen Isabella.[68]

Pedro de Zúñiga y Manrique de Lara, firstborn of the duke of Arévalo, sought reconciliation with the Monarchs of Castile in December 1475. Queen Isabella did not exercise reprisals against Iñigo de Zúñiga but swore that she would never return the castle of Burgos to the House of Zúñiga, reintegrating it into the crown of Castile. The House of Zúñiga, unhappy with the little support provided by the king of Portugal, who let the castle of Burgos fall without risking a short-distance march, decided to suspend the fight and remained in strict neutrality from January 1476.[69] On 10 January Isabella I gave orders to Álvaro de Zúñiga y Manrique de Lara, son of the duke of Arévalo and Prior to the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, to fight the king of Portugal.[70]

Neutrality of the Duke of Arevalo and pact with Queen Isabella

On 1 March 1476 the armies of the Catholic Monarchs achieved a great victory against the armies of King Afonso V of Portugal at the Battle of Toro. The Portuguese king retreated and abandoned the civil war. After this battle, the entire House of Zúñiga, for whom the civil war had been a tremendous family struggle, recognized the Catholic Monarchs. Between March and April 1476, Álvaro de Zúñiga y Guzmán, as the eldest relative of the House of Zúñiga, negotiated a pact with Queen Isabella. The queen was mindful that the Zúñiga had provided her with services that compensated for the initial rebellion and could not be forgotten.[71] The agreements with the Catholic Monarchs were signed on 10 April[72] and confirmed by the monarchs on April 13.[72] The main points of this agreement were:

- The House of Zúñiga was to raise banners for the Catholic Monarchs in all their domains, and from then on they were to keep a firm and loyal allegiance.

- The lordship of Arévalo, previously belonging to Isabella's mother, was to be given to Isabella.

- Iñigo de Zúñiga y Avellaneda, alcaide of the fortress of Burgos, would receive compensation for the alcaidaria and possession of the castle in addition to an annual rent or lordship, reverting the castle to the Crown of Castile.

- Juan de Zúñiga y Pimentel, son of the dukes of Arévalo, who already held a pontifical appointment, was recognized and confirmed as master of the Order of Alcántara.[3]

- Fernando de Zúñiga y Pimentel, another of Álvaro de Zúñiga's sons, receives ecclesiastical benefits.

- The Duke of Arévalo received back all his offices, trades and incomes.

- The Zúñiga reconciled with the noble houses with which they had been in conflict (Velasco, Álvarez de Toledo, Mendoza, etc.).

The Duke of Arévalo castellanizes his family name to Zúñiga, replacing the previous forms Stunica, Stúñiga, and Estúñiga.

King Afonso V of Portugal and his army abandoned Toro in May 1476. Queen Isabella remained in Tordesillas with her army guarding the region. Pedro de Zúñiga y Manrique de Lara battles with those loyal to Isabella on the border with Portugal and takes command of the defense of that border in the spring of 1476.[73] In late 1476 terrible fights are fought in Trujillo for the title of master of the Order of Alcántara, disputed by Juan de Zúñiga y Pimentel and Alonso de Monroy. The Duke of Arévalo helps his son and takes charge of Trujillo. Alonso de Monroy seeks the support of the king of Portugal and rebels in 1478.[74]

The Catholic Monarchs declared the majorat of the House of Zúñiga inalienable in 1477.[75] This declaration offered a guarantee to the firstborn of the House of Zúñiga. On 1 January 1480 the Catholic Monarchs granted Álvaro de Zúñiga y Guzmán the titles of duke of Plasencia and count of Bañares, which would be ratified on 16 February 1506.[76] As provided for in the pact with the Catholic Monarchs, Álvaro de Zúñiga renounced possession of Arévalo on 25 July 1480.[77] On 31 December 1480 he was appointed justicia mayor of Castile by the Catholic Monarchs.[78] In 1480 further negotiations take place between Zúñiga and the monarchs, in which the monarchs agree on the fulfillment of the pact of 1476 and grant further privileges,[79] such as the restitution of lands in Seville and the fortress of Rodezno.[80] All the privileges of Álvaro de Zúñiga, Duke of Plasencia, are confirmed in a royal letter of 6 February 1481.[81]

Later years

Queen Isabella granted the title of duke of Béjar to Álvaro de Zúñiga in 1458.[82]The lordship of Béjar had been granted to Álvaro's grandfather, Diego López de Estúñiga, by King Henry III of Castile in 1396.

The dukes of Plasencia and Béjar made a promise to erect a Dominican church and convent in Plasencia in honor of Saint Vincent Ferrer, the saint who supposedly saved the life of their son Juan, who would become the master of Alcántara, Archbishop of Seville, and primate of Spain. The construction of the church and convent began in 1477, and on 13 April 1487 the complex was blessed by Friar Pedro de Villalobos, the apostolic visitor of the diocese of Plasencia. The dukes, cultured figures of the Renaissance, also founded the first college in Extremadura to remedy the reputation of ignorance of the men of the region, more skilled in arms than in letters.[83]The alcaldeans of the fortress of Plasencia paid formal homage to the duke in 1486 and 1488.[84]

Álvaro de Zúñiga y Guzmán died in Béjar on 10 June 1488.[85] In his will of 21 July 1486, before the public registrars of Béjar (Juan González de la Puente), Ciudad Real (Diego López), and Plasencia, he left his successor as his grandson Álvaro II de Zúñiga y Guzmán, son of his deceased firstborn Pedro de Zúñiga y Manrique de Lara.[86] The Catholic Monarchs confirmed by royal decree of 10 June 1488, authorizing the duke of Plasencia and Béjar to declare his grandson Álvaro as successor to his house, titles, and states.[76] Álvaro II ordered the burial of his grandfather in the chancel next to the Gospel of the church of San Vicente Ferrer in Plasencia.[87]

Titles

In 1449, he was appointed by Henry IV justicia mayor (chief judge)[88] and alguacil mayor (bailiwick) of Castile, titles that were reinstated by Isabella in 1480.[89] He was declared the first fnight of the Realm by Henry IV on 3 May 1464,[90] and alcalde of the fortress of Burgos,[91] administrator of the grand master of the Order of Alcántara,[92] 2nd count of Plasencia[93] and 1st duke of Arévalo in 1469.[94] These titles would be withdrawn by the Catholic Monarchs, the same who would later grant him the titles of 1st duke of Plasencia (1476),[95] 1st count of Bañares (1485)[91] and 1st duke of Béjar (1485).[1]

Other titles of Álvaro de Zúñiga: rico-homem of Castile, lord of Zúñiga, Béjar, Bañares,[91] Mendavia, and, by inheritance from his mother Isabel de Guzmán y Ayala, marquis and lord of Gibraleón.[1]

Notes

- ↑ Other spellings for Zúñiga: Estúñiga, Stúñiga and Stunica.

References

- 1 2 3 "Álvaro de Zúñiga y Guzmán - I Duque de Béjar". Fundación Casa Ducal de Medicelo. Archived from the original on 15 September 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- 1 2 "AER, Archivo SNAHN, Signatura OSUNA,C.215,D.7".

- 1 2 3 Sánchez Loro (1959, p. 283)

- ↑ Fernández (2006, pp. 96–97)

- ↑ Sánchez Loro (1959, pp. 531)

- 1 2 "AER, Archivo SNAHN, Signatura OSUNA,C.314,D.36".

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, pp. 151–153)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, p. 20)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, p. 163)

- ↑ "AER, Archivo SNAHN, Signatura FRIAS,C.5,D.9".

- ↑ "AER, Archivo SNAHN, Signatura FRIAS,C.1,D.20".

- ↑ "AER, Archivo SNAHN, Signatura OSUNA,CP.94,D.28".

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, p. 208)

- ↑ Sánchez Loro (1959, p. 70)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, pp. 209–211)

- ↑ Sánchez Loro (1959, p. 71)

- ↑ "AER, Archivo SNAHN, Signatura OSUNA,C.299,D.1-5".

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, pp. 219–223)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, p. 226)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, p. 229)

- ↑ "AER, Archivo SNAHN; Signaturas OSUNA,C.216,D.45-48 y OSUNA,CP.86,D.4".

- ↑ Sánchez Loro (1959, p. 90)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, p. 230)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, p. 236)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, p. 237)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, pp. 240–241)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, p. 255)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, p. 243)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, p. 256)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, p. 269)

- ↑ Sánchez Loro (1959, p. 95)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, pp. 256–257)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, p. 257)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, p. 258)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, pp. 259–260)

- ↑ "AER, Archivo SNAHN & Signaturas FRIAS,C.15,D.3 y FRIAS,C.14,D.16".

- ↑ "AER, Archivo SNAHN & Signatura FRIAS,C.9,D.24".

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, pp. 260–261)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, p. 265)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, pp. 266–267)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, p. 268-269)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, pp. 270, 302)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, p. 271)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, p. 276)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, pp. 277–278)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, p. 281)

- 1 2 Menéndez y Pidal (1986, p. 282)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, p. 289)

- ↑ "AER, Archivo SNAHN FRIAS,C.16,D.22".

- ↑ "AER, Archivo FRIAS,C.16,D.23".

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, p. 297)

- ↑ "AER Archivo SNAHN Signatura OSUNA,C.279,D.3".

- ↑ "AER Archivo SNAHN Signatura OSUNA,C.279,D.14".

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, p. 300)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, p. 298)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, pp. 301–302)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, p. 306)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1986, p. 313)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1983, p. 99)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1983, p. 110)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1983, p. 100)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1983, pp. 125–127)

- ↑ "AER Archivo SNAHN Signatura OSUNA,C.279,D.5".

- ↑ "AER Archivo AGS Signatura RGS,147506,507".

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1983, p. 131)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1983, p. 142)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1983, p. 144)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1983, p. 150)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1983, p. 150-152)

- ↑ "AER Archivo AGS Signatura RGS,147601,16".

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1983, pp. 167–169)

- 1 2 "AER Archivo AGS Signatura PTR,LEG,11,DOC.13".

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1983, p. 252)

- ↑ Menéndez y Pidal (1983, p. 308)

- ↑ "AER Archivo AGS Signatura RGS,LEG,147707,309".

- 1 2 "AER Archivo SNAHN Signatura OSUNA,C.318,D.5-6".

- ↑ "AER Archivo SNAHN Signatura OSUNA,CP.88,D.26".

- ↑ "AER Archivo SNAHN Signatura OSUNA,C.217,D.28-30".

- ↑ "AER Archivo AGS Signatura PTR,LEG,11,DOC.26".

- ↑ "AER Archivo AGS Signatura RGS,LEG,148012,121-133".

- ↑ "AER Archivo SNAHN Signatura OSUNA,CP.30,D.2".

- ↑ "AER Código ES.41168.SNAHN/1.130.71".

- ↑ Fernández (2006, pp. 107–110)

- ↑ "AER Archivo SNAHN Signatura OSUNA,C.300,D.9".

- ↑ Sánchez Loro (1959, p. 544)

- ↑ Sánchez Loro (1959, pp. 943–976)

- ↑ Fernández (2006, p. 113)

- ↑ "AER, Archivo SNAHN, Signatura OSUNA,CP.85,D.3".

- ↑ "AER, Archivo SNAHN, Signatura OSUNA,C.218,D.155-156".

- ↑ Ceballos-Escalera y Gila (2000, p. 271)

- 1 2 3 "AER, Archivo SNAHN, Código de Referencia: ES.45168.SNAHN/130.71".

- ↑ "AER, Archivo SNAHN, Signatura RGS,LEG,149206,96".

- ↑ "AER, Archivo SNAHN, Signatura OSUNA,CP.86,D.5".

- ↑ "AER, Archivo SNAHN, Signatura OSUNA,C.279,D.12-13".

- ↑ "AER, Archivo SNAHN, Signatura OSUNA,C.298,D.2".

Bibliography

- "AER - Pares, Portal de Archivos Españoles". Ministério da Cultura de Espanha. Retrieved 8 November 2010.

- Atienza, Julio (1959). Nobiliario Español (in Spanish). Madrid: Editorial Aguilar.

- Ceballos-Escalera y Gila, Alfonso de, Marqués de la Floresta (2000). La Insigne Orden del Toisón de Oro (in Spanish). Madrid: Fundación Carlos III, Palafox & Pezuela. ISBN 84-930310-2-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Fernández, Fray Alonso (2006). Historia y Anales de la Ciudad y Obispado de Plasencia (facsimile edition of the 1627 original) (in Spanish). Vol. I. Badajoz: Cicon Ediciones. ISBN 84-95371-20-0.

- Menéndez y Pidal, Ramón (1986). Historia de España, Tomo XV, Los Trastámaras de Castilla y Aragón en el siglo XV (in Spanish). Madrid: Editorial Espasa-Calpe SA. ISBN 84-239-4817-X.

- Menéndez y Pidal, Ramón (1983). Historia de España. Tomo XVII, La España de los Reyes Católicos (in Spanish) (2 ed.). Madrid: Editorial Espasa-Calpe SA. ISBN 84-239-4819-6.

- Sánchez Loro, Domingo (1959). El Parecer de un Deán (Don Diego de Jerez, Consejero de los Reyes Católicos, Servidor de los Duques de Plasencia, Deán y Protonotario de su Iglesia Catedral) (in Spanish). Cáceres: Biblioteca Extremeña, Publicaciones del Movimiento edición, Tipografía, El Noticiero.

- Vilar y Pascual, Luis (1864). Diccionario Histórico Genealógico y Heráldico de las Familias Ilustres de la Monarquía Española (in Spanish). Vol. VII. Madrid.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)