Árpád Göncz | |

|---|---|

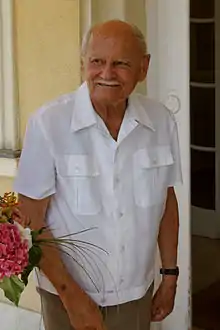

Göncz in 1999 | |

| President of Hungary | |

| In office 2 May 1990[a] – 4 August 2000 | |

| Prime Minister | |

| Preceded by | Mátyás Szűrös (interim) |

| Succeeded by | Ferenc Mádl |

| Speaker of the National Assembly | |

| In office 2 May 1990 – 3 August 1990 | |

| Preceded by | István Fodor |

| Succeeded by | György Szabad |

| Member of the National Assembly | |

| In office 2 May 1990 – 3 August 1990 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 10 February 1922 Budapest, Kingdom of Hungary |

| Died | 6 October 2015 (aged 93) Budapest, Hungary |

| Political party | |

| Spouse |

Zsuzsanna Göntér (m. 1947) |

| Children | 4, including Kinga |

| Parent |

|

| Alma mater | Pázmány Péter University |

| Profession |

|

| Signature | |

| a. ^ Acting until 3 August 1990 | |

Árpád Göncz (Hungarian: [ˈaːrpaːd ˈɡønt͡s]; 10 February 1922 – 6 October 2015) was a Hungarian writer, translator, agronomist, and liberal politician who served as President of Hungary from 2 May 1990 to 4 August 2000. Göncz played a role in the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, for which he was imprisoned for six years. After his release, he worked as a translator of English-language literary works.

He was also a founding member of the Alliance of Free Democrats (SZDSZ) and Speaker of the National Assembly of Hungary (de facto head of state) before becoming president. He was Hungary's first freely elected head of state, as well as the first in 42 years who was not a communist or a fellow traveller.

He was a member of the international advisory council of the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation.[1]

Biography

Early life (1922–1945)

Árpád Göncz was born on 10 February 1922 in Budapest into a petty bourgeois family of noble origin as the son of Lajos Göncz de Gönc (1887–1974), who worked as a post officer, and Ilona Haimann (b. 1892). The Roman Catholic Göncz family originated from Csáktornya, Zala County (today Čakovec, Croatia), where Göncz's great-grandfather, Lajos Göncz, Sr. was a pharmacist. He later participated in the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 and following the defeat, he was sentenced to nine years in prison.[2] Árpád Göncz's father, Lajos Göncz was also a successful tennis player, who participated in the 1924 Summer Olympics, where he was defeated by René Lacoste in men's singles in the second round.[3] Árpád Göncz's parents divorced when he was six years old, thus his relationship with his father became tense in the following years.[4] Göncz's mother, who was a Unitarian, was born in Transylvania, she had Jewish and Székely roots. She became an orphan as a child and after a brief spell in an orphanage, she was raised by the merchant Báthy family from Budapest.[4]

After finishing four-grade elementary school, Göncz began his secondary studies at the Werbőczy Secondary Grammar School in 1932. There he involved himself in the activity of the Hungarian Scout Association. Scouting opened Göncz's eyes to social issues, particularly with regard to the problems of the poor peasantry, as he said in a later interview.[5] Göncz joined the Pál Teleki Work Group which was formed in 1936 by Pál Teleki, an influential interwar politician and Prime Minister of Hungary, also Hungary's Chief Scout. The work group was an important seminary and forum for the university students. The programme emphasized the relevance of the nation, family and community and the good knowledge of Hungarian history and geography. In the next years, key figures from the Independent Smallholders' Party, e.g. Endre Bajcsy-Zsilinszky, had joined the work group.[6] His political view was also influenced by the népi-nemzeti ("rural-national") ideological movement since the 1930s. The group of the so-called "folk writers" (Hungarian: népi írók), including Zsigmond Móricz or János Kodolányi, expressed critique of capitalism and emphasis on peasant society and land reform. Göncz also stressed he represented the same political view as liberal political theorist István Bibó.[7] In December 1938, Göncz, in a short essay in Magyar Cserkész ("Hungarian Scout"), welcomed the Hungarians' entry into Komárno in accordance with the First Vienna Award.[8]

Göncz graduated in law from the Budapest Pázmány Péter University of Arts and Sciences in 1944. During his academic years, he was exempted from conscription in the Second World War. Meanwhile, Hungary was occupied by Germany on 19 March 1944. In December, Göncz was conscripted into the 25th Reserve Mountain Infantry Battalion of the Royal Hungarian Army and ordered to Germany; however, he deserted and joined the resistance movement.[9] In late 1944, Göncz found himself in Budapest when the Red Army encircled the Hungarian capital, beginning the Siege of Budapest. The resistance Hungarian Front formed to oppose the Nazi regime with several regional branches, including the Freedom Front of Hungarian Students (MDSZ) which established officially on 7 November 1944, during the Arrow Cross Party government. Göncz joined the Táncsics Battalion in December 1944, where he took part in partisan actions against the Arrow Cross regime in Budapest.[10] After the war he went on to study agricultural science.[11]

Early political career and retreat (1945–1956)

Following the Soviet occupation of Hungary, Göncz joined the anti-communist Independent Smallholders' Party (FKGP), which won a sweeping victory (57.03%) in the November 1945 parliamentary election, however the party had to yield to Marshal Kliment Voroshilov (Chairman of the Allied Control Commission), who made it clear that a grand coalition in which the Communists preserved the gains already secured (that is, the Ministry of the Interior and control over the police) was the only kind of government acceptable to the Soviets.[12] Göncz refused to run as an individual parliamentary candidate, because he did not feel ready for becoming MP. Instead he served as the personal assistant of Béla Kovács, the General Secretary of the Independent Smallholders' Party, who was responsible for running the party machine.[13] Göncz later called his job as an "unpleasant time in his life" due to the nature of the function, nevertheless he admired and respected Kovács and remembered him as a "statesman" in a later interview.[14]

Beside his secretary position, Göncz also edited weekly party newspaper Nemzedék ("Generation"). He also served as leader of the party's youth organization in Budapest for a time.[15] Over the next two years, the Communists (MKP) pressured the Smallholders' Party into expelling their more courageous members as "fascists" and fascist sympathizers as part of Communist leader Mátyás Rákosi's "salami tactics". On 25 February 1947, Béla Kovács was arrested unlawfully and taken to the Soviet Union without a trial in Hungary. Following that Göncz was also arrested in conjunction with a visit to Romania in late 1946, where he had negotiated with ethnic Hungarian politicians. He was detained and interrogated for three weeks before release.[16]

By the 1949 parliamentary election, the FKGP was absorbed into the Hungarian Independent People's Front (MFNF), led by the communists, and Göncz became unemployed. After that, he worked as a manual labourer (welder metalsmith and pipe fitter)[17] and also enrolled in a correspondence course of the Gödöllő Agricultural University, where he specialised in soil erosion and protection. Göncz then used his knowledge working as an agronomist at the Talajjavító Vállalat (Soil Improvement Co.) until the outbreak of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 against the communist rule.[16]

1956 Revolution and aftermath (1956–1957)

Göncz played an active role in the work of the newly formed Petőfi Circle (Hungarian: Petőfi Kör), which established by reformist intellectuals under the auspices of the Union of Working Youth (DISZ), mass youth organization wing of the ruling communist Hungarian Working People's Party (MDP), in March 1955. The circle held twelve meetings in the first half of 1956.[18] As an agronomist, Göncz expressed his opinion on the Soviet agricultural model during one of the forums. On 17 October 1956, he participated in an agricultural debate ("Kert-Magyarország?") at the Karl Marx University of Economic Sciences. There he criticized again the Soviet model considered unsuitable for the Hungarian conditions. Göncz also lay emphasis on free peasant education.[19]

In a June 1995 speech, Göncz recalled the 1956 events as a "turning point" in his life which determined his fate until the end of his life,[20] despite the fact that he did not participate in the armed resistance and uprising. On 23 October 1956, he was present at the peaceful mass demonstration, which marched in front of the Hungarian Parliament Building, along with his eldest daughter Kinga, who was nine years old at that time.[21] Göncz's role in the October 1956 events remained fragmented. By 29 October 1956, he assumed a political role in the events. He participated in a meeting at Prime Minister Imre Nagy's house, when Nagy was informed about the Suez Crisis and the Prime Minister said "Gentlemen! From now on, we need to discuss another thing because there is a dangerous possibility of a Third World War". Göncz worked as an activist in the newly recreated Hungarian Peasant Alliance during the revolution.[21] In a 1985 interview, Göncz said he sympathized with the political vision of Imre Nagy. He also added, that he would join a Nagy-led Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party (MSZMP), if the Soviet intervention does not take place. Göncz noted the Nagy government and the new communist party would have started with a clean slate.[22] Sociologist Péter Kende has said Göncz's belief in "democratic socialism" was similar to that of István Bibó.[23]

After the Soviet intervention on 4 November 1956, János Kádár established a pro-Soviet government. The Revolutionary Council of Hungarian Intellectuals, members were writers, journalists etc., issued statements of protest against the Soviet army's invasion and appealed for help and mediation from the Western world. Göncz participated in the writing of several memoranda. One of the most influential writings was the Draft Proposal for a Compromise Solution to the Hungarian Question by intellectual István Bibó, who also served as Minister of State in the second and third government of Imre Nagy. Göncz took part in the debates on the proposal.[24] Göncz had a good relationship with charge d'affaires Mohamed Ataur Rahman from the Indian Embassy in Budapest,[25] thus he was also able to make contact with the Government of India who tried to mediate between the Hungarian and the Soviet governments following the revolution.[24] Formerly, during the intense days, Prime Minister of India Jawaharlal Nehru expressed his sympathy and compassion towards the Hungarian freedom fighters, nevertheless India remained cautious and abstained in the UN General Assembly voting, which called on the Soviet Union to end its Hungarian intervention. As a result of the intercession of Göncz, the Indian government became more determined in the Hungarian issue.[25] He handed over Bibó's draft proposal to charge d'affaires Rahman in December 1956, however India's mediation attempt ended in failure due to lack of interest in the Soviet Union.[26]

Göncz also helped to transfer a manuscript of Imre Nagy ("On Communism in Defense of New Course") abroad, through the assistance of László Regéczy-Nagy, driver to Christopher Lee Cope, head of the British Legation in Budapest. They hoped the manuscript might have helped to rescue Imre Nagy from show trial and execution.[27] Cope forwarded the manuscript to the emigrant Hungarian Revolutionary Council in Strasbourg, and the document was translated into several languages for several countries, including Italy, France and West Germany.[28] Before his arrest, Göncz was campaigning for the Hungarian Aid (Hungarian: Magyar Segély) movement. Göncz organized to donate the emigrant Hungarians' support for families in need of help.[29]

Prison years (1957–1963)

He was arrested on 28 May 1957, along with István Bibó, on the order of Minister of the Interior Béla Biszku.[30] In the forthcoming months, Bibó, Göncz and Regéczy-Nagy were interrogated, isolating from each other by the secret police in connection with their relationships with India and the Western block.[31] Once the prosecutor said to Göncz that "the traitor deserved to hang twice."[32] Göncz and his inmates were charged with "organizing the overthrow of the Hungarian people's democratic state." Göncz was secretly tried, found guilty, and sentenced to life imprisonment without the possibility of appeal on 2 August 1958, some weeks after the secret trial and execution of Imre Nagy. Later Göncz believed that he could avoid the capital punishment only due to Nehru's intervention.[33] Dae Soon Kim, Göncz's biographer also argued it might be possible that the Indian premier' diplomatic efforts impacted on the severity of penalties regarding the Göncz and Bibó trials.[34]

Göncz began his years in prison at Budapest Penitentiary and Jail (Gyűjtőfogház) in August 1958. He spent his punishment among hundreds of political prisoners, such as Tibor Déry, Zoltán Tildy, István Bibó and Imre Mécs. Göncz was isolated and separated from the outside world, visitors were permitted for only ten minutes in every six months and correspondence was allowed in every three months for the political prisoners.[35] Later Göncz was transferred to the Vác prison.

In Vác, the conditions were freer; Göncz had spent the time learning to read and write English.[36] The political prisoners were able to obtain literary works from the Western world, including the memoires of politicians Winston Churchill and Charles de Gaulle. According to György Litván, the senior party functionaries, who did not speak foreign languages, established a "translation agency" in the Vác prison to learn about the information available to Western public opinion.[37] Göncz, beside political pamphlets, also translated John Galsworthy's The Forsyte Saga, transferring from the prison by Litván, which laid the foundation of his translation career after release.[36] Imre Mécs said, a cohesive community of '56 democratic-minded generation emerged within the walls of the Vác prison, where there were constant political discussions and debates.[36]

In 1960 he participated in the political prisoners' hunger strike of the Vác prison, because, despite the promises of Kádár, most of the oppositional intellectuals and freedom fighters were not pardoned, unlike former communist officials, who had significant role in building of the Stalinist dictatorship before 1956, such as Mihály Farkas and Gábor Péter.[38] The government decided to separate the prisoners, Bibó and Göncz were transferred to Márianosztra, while Litván and journalist Sándor Fekete were sent back to the Gyűjtőfogház.[38] Finally, János Kádár ordered a mass amnesty in March 1963 in exchange for his government's international recognition by the United Nations. Along with more than 4000 other revolutionaries and freedom fighters, Göncz was released from prison under amnesty in July 1963, three months after István Bibó.[39]

Literary career (1963–1988)

In the following decades, he worked as a specialized translator, translating over a hundred literary works, and a writer of English prose. Some of his notable translations include E. L. Doctorow's Ragtime and World's Fair,[40][41] Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, Thomas Wolfe's Of Time and the River, William Faulkner's Sartoris, The Sound and the Fury, the latter being referred by Göncz to as his "greatest challenge."[17]

His most famous translation work is J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings trilogy.[42] Initially, art critic Ádám Réz began to translate The Fellowship of the Ring, however after the translation of eleven chapters (texts and poems), the main terms and concepts, he stopped the work because of his increasingly severe illness. Réz died in 1978 and his manuscript remained unfinished for the next few years. Göncz later took over the project, working on the prose in Tolkien's novel, while the poems and songs were translated by Dezső Tandori. Finally, the work was published by Gondolat Kiadó in 1981, for the first time in Hungary.[43] In January 2002, Göncz was present at the Hungarian premiere of the movie adaptation of The Fellowship of the Ring.[44]

Göncz continued his career as a translator with many important works, including Faulkner's Absalom, Absalom! and A Fable, Ernest Hemingway's Islands in the Stream, Malcolm Lowry's Under the Volcano, William Styron's Lie Down in Darkness and The Confessions of Nat Turner, John Ball's In the Heat of the Night, Colleen McCullough's The Thorn Birds, Yasunari Kawabata's The Lake, John Updike's Rabbit Redux and Rabbit is Rich, and The Inheritors, Pincher Martin, The Spire and The Pyramid and Rites of Passage by William Golding.[45]

His own works include both novels and dramas; Men of God (1974), Sarusok (1974), Magyar Médeia (1976), Rácsok (1979), Találkozások (1980) are among the most notable. He is also the author of Encounters (essays, 1980), Homecoming and Shavings (short stories, 1991), Hungarian Medea (play, 1979), Iron Bars (play, 1979), Balance (play, 1990).[46] Göncz worked incredibly hard for ten hours per day with no pay. For instance, in 1982 he visited the United States on an academic conference with only $5 in his pocket.[17] He won the Attila József Prize in 1983. In 1989 he won the Wheatland Prize, and two years later the Premio Meditteraneo.[47] From 1989 to 1990 he was President and later Honorary President of the Hungarian Writers' Union.[48] The person of Göncz was acceptable for both the liberal and "rural-national" intellectuals because of his past.[49]

Return to politics (1988–1990)

By the beginning of the 1980s, the Kádár regime had increasingly indebted and was in ideological and legitimation crisis. Opposition movements established one after another; a group of intellectuals founded the Hungarian Democratic Forum (MDF) in Lakitelek in September 1987. In early 1988, Göncz was a co-founding member of the Historical Justice Committee (TIB) civil organization,[50] which intended to revise the official communist stigmatization of the 1956 revolution. The organization was led by Erzsébet Nagy, daughter of Imre Nagy. The TIB demanded the worthy reburial of Nagy and the other executed persons.[51]

When the security forces violently disbanded a peaceful demonstration in Budapest on 16 June 1988, the 30th anniversary of Nagy's execution, Árpád Göncz, as Vice Chairman of the Historical Justice Committee, wrote a letter to General Secretary and Prime Minister Károly Grósz, Kádár's successor to protest against the police action and called on the regime to face its past.[52] In a response letter, Grósz rejected the implementation of demanded political reforms.[53] Finally (due to the appointment of the reformist Miklós Németh as Prime Minister in November 1988) the reburial took place in the next year on 16 June, Göncz took part in organizing, as he proposed, there was a fifth empty coffin beside the four martyrs' for the anonymous heroes and freedom fighters of the revolution. Göncz was the one who officially opened the ceremony.[54]

On 1 May 1988, Göncz also participated in the foundation of the Network of Free Initiatives (Hungarian: Szabad Kezdeményezések Hálózata; SZKH), the predecessor organization of the Alliance of Free Democrats (SZDSZ).[55] Initially, SZKH was a loose alliance of various independent civil groups, which intended to become an umbrella organization like the Solidarity in Poland. However, because of the widespread pluralism, the SZKH's operation proved to be slow and time consuming in the midst of accelerated events, thus on 13 November 1988, the majority of the organization decided to found the SZDSZ, Göncz was also a co-founding member and helped the formulation of the founding declaration. Ferenc Miszlivetz said, Göncz was an observer rather than an active proponent in the following rallies.[56] In addition to MDF and SZDSZ, the third major anti-communist block was the liberal Alliance of Young Democrats, later known mostly by its acronym Fidesz. Göncz's former party, the Independent Smallholders' Party (FKGP) was re-established in those days, he visited the party's inaugural session at the Pilvax Café but, for him, it was not attractive anymore, as most of the former members of the FKGP were already dead or stayed in emigration.[57] Göncz considered the old debates between the "rural-national" and "urbanist" trends are outdated and detrimental after decades of communist rule, his liberal ideology became more dominant by 1988.[58]

The reburial of Imre Nagy proved to be a catalyst event; the hard-line Grósz was outranked by a four-member collective presidency of the reformist wing within the MSZMP on 26 June 1989. The ruling communist party began discussions with the opposition groups within the framework of the so-called Round Table Talks. The question of the post-communist presidential position was one of the most problematic disputes between the parties. The MSZMP suggested a directly elected semi-presidential system, however this proposal was strongly refused by the sharply anti-communist SZDSZ and Fidesz,[59] because the reformer communist Imre Pozsgay was the most popular Hungarian politician in those months. In August 1989, József Antall, leader of the MDF presented a new proposal (ceremonial presidential system with indirect elections by the parliament, but the first election by the people). Excluding SZDSZ, Fidesz and LIGA, the remaining five opposition groups and the MSZMP accepted and signed the proposal.[60] However, following collecting signatures by Fidesz and SZDSZ, a four-part referendum was held on 26 November 1989, where the voters chose "yes" for the question of "Should the president be elected after parliamentary elections?"[61]

The Hungarian Democratic Forum (MDF) won the first democratically free parliamentary election in March 1990, while SZDSZ came to the second place with 92 MPs, including Göncz, who gained mandate from the party's Budapest regional list.[62] József Antall became Prime Minister and entered coalition with FKGP and the Christian Democratic People's Party (KDNP). As there were several two-thirds laws according to the Hungarian Constitution, Antall concluded pact with SZDSZ, under which the liberal opposition party could nominee a candidate for the position of President of Hungary, in exchange for contribution to the constitutional amendments.[63] According to some opinions, the pact concluded specifically for the person of Árpád Göncz.[64]

József Antall and Árpád Göncz knew each other through the re-establishment of the FKGP. Their relationship was characterized by mutual trust according to contemporary reports. In addition, Antall's father, József Antall, Sr. was a prominent FKGP-member and friend of Béla Kovács in the 1940s. Political scientist László Lengyel argued that Göncz was a relatively unknown figure for the MDF leadership, who considered him "far more moderate" than other SZDSZ politicians, contrary to other candidate aspirants, like Miklós Vásárhelyi or György Konrád.[64] Göncz's well-known anti-communism was also an advantage for him.[65] There is also a third possible explanation that Antall did not want to choose a head of state from his own party (especially Sándor Csoóri), fearing from a build of a second power base within MDF.[66] Thus in the newly formed parliament's inaugural meeting on 2 May 1990, Göncz was elected Speaker of the National Assembly. As Speaker, he served as Acting President until the August indirect presidential election according to the Constitution.[62]

Presidency (1990–2000)

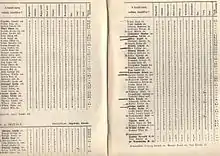

| Göncz's political activities and role during his presidency (1990–2000)[67][68] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Presidential activities | 1990–1994 (Antall–Boross) | 1994–1998 (Horn) | 1998–2000 (Orbán I) |

| Parliamentary speeches | 22 | 4 | 2 |

| Foreign trips (days) | 49 (215) | 79 (273) | 35 (119) |

| Signing international treaties | 1 | – | – |

| Initiating referendums | – | – | – |

| Self-proposed laws | 5 | – | – |

| Initiating extraordinary parliamentary sessions | – | – | – |

| Participating in parliamentary sessions | 71 | 15 | 12 |

| Constitutional vetoes | 7 | – | 1 |

| Political vetoes | – | 2 | – |

| Political role | 1990–1994 (Antall–Boross) | 1994–1998 (Horn) | 1998–2000 (Orbán I) |

| Pro-President parties | SZDSZ (MDF) | MSZP SZDSZ | MSZP SZDSZ |

| Parliamentary majority | Right-wing (MDF–FKGP–KDNP) | Left-wing (MSZP–SZDSZ) | Right-wing (Fidesz–FKGP–MDF) |

| Perception of presidential role | Counterbalance | Supportive/Symbolic | Symbolic |

| Conflicts with government | Frequent | Minimal | Rare |

| Activity in daily politics | Significant | Diminished | Diminished |

| Political weight | Medium/Strong | Weak | Weak |

First term (1990–1995)

On 4 August, he was elected for a full term as president by the National Assembly by 295 votes to 13,[69][70] thus becoming Hungary's first democratically elected head of state. He was also Hungary's first non-Communist president since the forced resignation of Zoltán Tildy 42 years earlier.[71] After taking the oath before the new legislative speaker György Szabad (MDF), Göncz stated in his inaugural speech that "I am not, I can not be a servant of parties, party interests. In my whole life, within and outside party, I served and I will serve for national independence, freedom of thought, freedom of faith in the idea of free homeland, and social justice with human rights without discrimination and exclusion." He also added, "I would like to serve the unprotected, the defenceless people, those, who lacked the means to protect themselves both in the "feudal crane feather world" [referring to Miklós Horthy's Hungary] and in the "world of more equals among equals" [i.e. the communist regime between 1945 and 1989]."[72]

Göncz was an avid supporter of Hungarian integration with the West, especially with the United Kingdom.[70] In May 1990, Charles, Prince of Wales and his wife Diana undertook an official visit to Hungary and made history by becoming the first members of the British royal family to visit a former Warsaw Pact country.[73][74] The royal couple were met at the airport by their host, newly elected interim President Göncz,[74] who later hosted an official dinner to welcome the royal couple.[74] Elizabeth II visited Hungary in May 1993, also welcomed by Göncz.[75] He argued in favor of Hungary's accession to NATO and the European Union. He was also an enthusiastic supporter of U.S. President Bill Clinton's "Partnership for Peace" in Central Europe.[76] As a result, in 2000, he was honored with the Vision for Europe Award for his efforts in creating a unified Europe.[77] Göncz's commitment towards the Western world earned some domestic negative criticism; in 1991, the far-right politician István Csurka, later defector from MDF and founder of the nationalist Hungarian Justice and Life Party (MIÉP) accused him of being a tool of France, Israel, and the United States.[17] During Göncz's presidency, Pope John Paul II visited Hungary twice, in August 1991 and September 1996. They had already known each other through a common Polish friend, before John Paul's papacy.[78]

His relationship with Prime Minister József Antall and his cabinet became tense in the coming years. Göncz filled a counterbalancing role to the conservative cabinet, according to the critics, he proved to be acting in the vested interests of his party, the SZDSZ. Critics also said Göncz failed to act for the unity of the nation as a non-partisan head of state with these anti-government steps.[79] However, as Dae Soon Kim notes, after a four-year Socialist government between 1994 and 1998, Göncz remained conflict-avoiding during the last two years of his presidency, when the right-wing Viktor Orbán governed the country as Prime Minister.[80] During the Antall government, strong state intervention and control in market economic trends remained significant.[81] Few months after the end of communism in Hungary, ideological conflicts tense between Antall and Göncz, who supported full privatization and reduction of the state.[82] Despite the earlier conflicts, the seriously ill Antall was awarded Grand Cross of the Hungarian Order of Merit by President Árpád Göncz on 11 December 1993, a day before his death.[83]

In October 1990, the so-called "taxi-blockade" broke out when the Antall government decided to raise the prices of petrol with 65 percent because of the Gulf War and oil supply disruptions in the Soviet Union. In response, the taxi drivers paralyzed traffic, when they blocked the main bridges in Budapest with their cars.[82] János Kis, the leader of the SZDSZ assured solidarity with the demonstrators. There have been unconfirmed news that the government wanted to put the law enforcement forces to eliminate the blockade (according to eyewitnesses, heavy military vehicles had been dispatched to the capital),[84] and Göncz, as Supreme Commander of the Hungarian Defence Force prevented this in a letter sent to Minister of the Interior Balázs Horváth.[85] Göncz mediated between the government and the taxi drivers, finally, a compromise was reached. After that the Hungarian government strongly denied that they had mobilized the armed forces, and also emphasised that Göncz had overreacted to, or misjudged, the given situation.[86] In April 1991, between Defence Minister Lajos Für and Árpád Göncz, a dispute arose over the right to be the Supreme Commander. The Constitutional Court concluded that the President is only the "ceremonial" leader of the army. The government said Göncz's principal reason were extending presidential powers and personal reputation among the people.[87] Political scientist Gabriella Ilonszki argued that the "taxi-blockade was the first test of the new democracy and Göncz sought to avoid the violent actions of both sides at all costs."[88] Nevertheless, the relationship between the MDF and SZDSZ deteriorated after the conflict.[88] In February 1991, Antall and Göncz clashed over the right of international representation, when Hungary signed the Visegrád Group, along with Poland and Czechoslovakia. Göncz argued the two other partner countries were represented by presidents Václav Havel and Lech Wałęsa, however Antall interpreted the Hungarian president's foreign policy powers more narrowly than Göncz due to the ambiguous Constitution.[89]

On 24 April 1991, the National Assembly passed the Law on Compensation which intended to provide a symbolic financial aid to victims of the communist regime.[90] The law was far from public expectations and generated debates in politics. On 14 May, Göncz sent the law to the Constitutional Court, asking for a judicial review. The Court ruled the law was unconstitutional in several aspects (arbitrary conditions etc.).[91] Accordingly, by spring 1992, the law was revised several times and has been accepted again, however Göncz refused to sign the law again in April 1993.[92] In a later interview, Göncz told that he missed the equality of rights in the law and the social consensus on the subject.[93] Göncz also did not sign the "Zétényi–Takács Law", named after two MDF politicians, which determined the communist political crimes are not subject to the statute of limitations. In November 1991 the law was submitted to the Constitutional Court by Göncz, which body (presided by László Sólyom) found the law as unconstitutional in March 1992 and later, after amendments, in June 1993.[94] There were clashes between moral justice and the new republic's commitment to the principle of the rule of law. Göncz's stance was influenced by three factors: avoid social division and polarisation, liberal political beliefs and the significance of social consensus.[95] Göncz refused the method of retroactive legislation and he feared that the law will be a tool for political revenge.[96] By contrast, journalist Szilvia Varró said "Göncz actively hindered the question of settling accounts with the communist past".[97] In a November 1991 report, Göncz stated "reckoning is necessary, but it should be made strictly within the framework of a state built on the rule of law." He added, after 1956 he was sentenced to life imprisonment during a secret trial without the possibility of appeal. " I strongly feel that no procedure should be repeated that could be found illegal in retrospect."[98]

Göncz was to deliver his annual memorial speech at Kossuth Square on the national day of 23 October 1992, when a group of far-right young skinheads and also '56 veterans hissed and booed, demanding Göncz's resignation, when the President appeared on the podium. The '56 veterans disapproved of his decision not to sign the "Zétényi–Takács Law" earlier. Göncz was not able to start his speech and left the podium without saying a word.[99] The government was accused of deliberately sabotage by the opposition, however Minister of the Interior Péter Boross said it was only a spontaneous event.[99] The SZDSZ claimed the police did not intervene in the events intentionally to protect Göncz. Prime Minister Antall rejected the accusation of political pressure.[100] In a June 2014 report, the Constitution Protection Office (AH) revealed that its predecessor organization, the Office of National Security (NBH) and the police forces escored the dozens of skinheads from the Keleti Railway Station to the Kossuth Square.[101] The most likely scenario is that there was no direct governmental connection indicating the event. It is possible that Antall and Boross knew about a potential provocation but they did not want to prevent it, as political analyst László Kéri considered it.[102]

The most stormy incident was the "Antall–Göncz media war" during the years of his first term. In July 1990, as consensus between the six parliamentary parties, the National Assembly appointed sociologists Elemér Hankiss and Csaba Gombár as presidents of the Magyar Televízió and Magyar Rádió, respectively.[103] In the summer of 1991, the Antall cabinet submitted new deputies of the state medias to counterbalance Hankiss and Gombár, however Göncz refused to countersign the appointments. Antall accused the President of overstepping his powers[70] and turned to the Constitutional Court, which ruled in September in that year that the President does not have a right of veto with regard to appointments, "unless those appointments endangered the democratic functioning of state institutions involved."[104] Göncz did not change his position and began to play for time, thus the Prime Minister again turned to the Constitutional Court, which on 28 January 1992 ruled that the President should sign the appointments "within a reasonable time."[104]

In May 1992, a liberal and constitutionalist, Göncz faced a parliamentary censure when he condemned the government for interfering with Hungary's state radio service and attempting to fire its director, Gombár.[70] In June 1992, the Antall cabinet wanted to replace Hankiss too, however Göncz refused to accept it, reasoning that he would wait until the adoption of the new media law, however by the end of 1992, the issue of media control was not resolved due to the abstention of the SZDSZ during the vote, which needed two-third majority.[105] In January 1993, Hankiss and Gombár resigned from the positions, referring to the media workers' livelihoods.[105] Göncz was rebuked by the Antall cabinet and the government parties for trying to block the new media law and re-organization of the structure of the media.[70] László Sólyom, President of the Constitutional Court also argued that Göncz exceeded his powers in the media issue.[106] The contrast between the MDF and the SZDSZ was again due to the ambiguity of the new Constitution (nominal or actual right of appointment).[107] Another key factor to the stalemate was the ambiguous ruling issued by the Constitutional Court (also under the influences of political parties, which delegated members) and its subsequent interpretations by Göncz and Antall. Göncz was able to play an active role in appointments due to the unclear term of "endangerment of democracy".[108] In those years, the Constitutional Court was usually under critics that it took on the legislative role of the parliament.[108]

In November 1993, Göncz gave an interview to the Italian daily newspaper La Stampa, which wrote "the Hungarian media had been placed in a serious situation because of the right-wing government's censorship" and also added "the President [Göncz] asks for international help!".[109] Imre Kónya, the leader of the MDF parliamentary group rejected the accusations and called for an explanation from Göncz, who responded that the disputed phrases were only the "journalist's individual interpretation." Nonetheless, the MIÉP said Göncz had denigrated Hungary's image by representing foreign interests and also attempted to set up an inquiry commission.[109] Göncz explained, although did not agree with the article's given title, it reflected the actual situation of the Hungarian media.[110]

Second term (1995–2000)

During the May 1994 parliamentary election, the Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP), legal successor of the ruling MSZMP in the one-party system before 1989, under the leadership of Gyula Horn, achieved a remarkable revival, winning an overall majority of 209 seats out of 386, up from 33 in 1990. Horn, despite winning an overall majority, decided to form a coalition with the formerly strong anti-communist Alliance of Free Democrats, giving him a two-thirds majority, to assuage public concerns inside and outside Hungary.[111] After 1994, Göncz was largely passive and insignificant, in contrary to his proactive role and style during the Antall and Boross governments (Péter Boross became Prime Minister after Antall died of cancer in December 1993).[112] Some of the critics suggested the one of the main reasons for this change was Göncz's political affiliation: as Szilvia Varró said she does not remember that "there was any issue on which he stood against Horn".[113] However, as mentioned above, Göncz remained passive too during Viktor Orbán's first cabinet (1998–2002),[80] which installed a more power-concentrated governing structure through the newly established Prime Minister's Office (MEH), led by István Stumpf.[114]

Dae Soon Kim writes, there are three factors responsible for Göncz's passivity; Firstly, his physical and mental condition has deteriorated in the second half of the 1990s. In December 1997, Göncz was hospitalized for two weeks for the treatment of dyspnea and a duodenal ulcer.[115] Secondly, the President's constitutional role clarified by that time. His proactive style became a subject of critics, and the Constitutional Court repeatedly ruled in favor of the Prime Minister, thus Göncz reviewed his previous position and turned to a ceremonial role.[116] Finally, before 1990, Hungary had never experienced the institution of parliamentary democracy, as a result Göncz had no prior example to follow, when he was elected President in August 1990.[117]

On 12 March 1995, the Horn government announced a series of fiscal austerity and economic stabilization measures, commonly known as the Bokros package.[118] On 13 June 1995, Göncz approved and signed the package, despite requests made by the opposition parties, especially MDF and Fidesz. After that the opposition turned to the Constitutional Court, which found numerous elements of the package as unconstitutional.[119] According to the fragmented opposition, Göncz followed his own party's interests when signed the laws. In addition, Fidesz MP Lajos Kósa connected Göncz's steps with the upcoming indirect presidential election about a week later.[119] Göncz was re-elected on 19 June 1995 for another five-year term[70] by the MSZP and SZDSZ coalition government (259 votes), defeating the candidate of the right-wing opposition, Ferenc Mádl (76 votes).[120] Dae Soon Krim argues that Göncz, among others, considered the Bokros package as a painful but necessary step, which was the only method to avoid economic collapse.[121]

Árpád Göncz refused to sign the Law of Incompatibility in January 1997, which was to provide the separation of the political and economical sphere by preventing MPs to maintain economic interests after their election. Following debates between the two governing parties, the Horn cabinet made a compromise solution: the MPs could keep their economical positions, if their post in business was acquired before they were elected to the National Assembly.[122] Göncz sent the law back to the parliament because of the "lack of equal rights and guarantee of free competition" and protection of privacy, however the Socialists adopted the law again in unchanged form.[122] Opposition politicians criticized Göncz, because he used only the presidential tool of "political veto", instead of "constitutional veto".[123] The President also questioned the revised version of the Law on Privatisation, which passed by the Horn government on 19 December 1996. Accordingly, the State Privatisation and Property Management Co. (ÁPV Co.) was authorised to transfer state properties to local governments and cooperatives without restriction, the coalition partner SZDSZ and the right-wing opposition parties (Fidesz, MDF, FKGP) opposed the law, citing reasons of corruption.[124] In January 1997, Göncz vetoed the law, returned it to the parliament for reconsideration.[124]

Shortly after the inauguration of the first Orbán cabinet, disagreement evolved around the presidential pardon between Göncz and the Ministry of Justice. Banker Péter Kunos, former CEO of Agrobank, who was arrested on corruption charges in November 1994, was sentenced to two years imprisonment in April 1998.[125] Kunos, citing health reasons, pleaded for a presidential pardon to Göncz, who accepted it on 9 November 1998.[125] However Minister of Justice Ibolya Dávid decided not to release Kunos.[126] The case was in the political spectrum as István Stumpf said SZDSZ had a close relationship with the Agrobank during Gyula Horn's government. Nevertheless, the Prime Minister's Office could not prove the minister's allegations with documents.[126] Ibolya Dávid's decision was popular among the general public. Stumpf later told that Dávid exploited the situation for her political career. Göncz's decision was influenced by lack of legal remedies in Kunos' second-degree trial (at first, Kunos was acquitted in July 1997).[127] Göncz thought the general public should not be affected in the outcome of some court cases.[128] Gabriella Ilonszki said, Göncz issued a pardon to Kunos on human grounds. "When the protection of democratic values and sympathy for an individual were in conflict, Göncz decided to stand by the individual", she added.[129]

Later life (2000–2015)

Göncz completed his five years of second term on 4 August 2000. He was replaced by Ferenc Mádl, who was elected President by the National Assembly's right-wing majority on 6 June 2000. In a ceremony at the Kossuth Square, he emphasized that he passes the position to Mádl with "respect and friendship". He also asked God's blessing on the successful work of Ferenc Mádl. Göncz added, during his 10-year term, he tried to keep in mind that the "democratic state can only be people-oriented organization".[130]

After his presidency, Göncz completely retired from politics and resided in a state residence at Béla király Street along with his wife until his death in October 2015.[131] In September 2000, he was appointed President of the Hungary in Europe Foundation which awarded literary prizes annually.[132] He gave a speech on 23 October 2000, where he told "the proliferating phrases during annual commemorations had overshadowed the actual events of the 1956 revolution."[133] In November 2000, Göncz became an honorary citizen of Budapest, awarded by the city's Mayor and fellow SZDSZ member Gábor Demszky.[134] In December 2000, a prize was founded by the United States, named after Göncz. U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright awarded the Göncz Prize to Erika Csovcsics, headmistress of the Gandhi School for the first time.[135]

In April 2003, Göncz participated in the signing ceremony of Hungary's join to the European Union in Athens, Greece.[136] In July 2003, Göncz was among the speakers at the so-called Szárszó meetings, a political forum of mostly left-wing intellectuals and politicians, organized by Tivadar Farkasházy.[137] In an open letter, along with Havel and Wałęsa, he demanded the release of political prisoners in Cuba from Fidel Castro in September 2003.[138]

On 10 February 2012, hundreds welcomed Göncz with serenades and speeches on the occasion of his 90th birthday, at the initiative of composer and songwriter János Bródy, writer György Konrád and former SZDSZ leader Gábor Kuncze.[139] Then-President Pál Schmitt also greeted his predecessor by telephone from the Arraiolos meeting in Helsinki and conveyed the best wishes of the summit's participants (heads of states).[140]

Personal life

On 11 January 1947, Göncz married Mária Zsuzsanna Göntér (16 November 1923 – 3 June 2020)[141][142] and had four children; two sons (Benedek, Dániel) and two daughters (Kinga and Annamária).[143] Kinga Göncz, who held various ministerial positions in the cabinets of Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsány and also a former Minister of Foreign Affairs from 2006 to 2009, is his daughter and eldest child. She was Member of the European Parliament between 2009 and 2014. In November 2012, Göncz's four children founded the Göncz Árpád Foundation to promote the presentation and research of their father's life and career, as well as cultivating the memory of the Hungarian democratic and liberal traditions. István Bibó, Jr., András Gulyás and János M. Rainer became advisory board members.[144]

Death and funeral

Árpád Göncz died on 6 October 2015 in Budapest, aged 93.[145][146][147] As the news emerged about Göncz's death, Hungarian lawmakers immediately held a minute of silence in parliament, where Deputy Speaker István Hiller said Göncz "was a legend already in his lifetime". Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and the governing Fidesz told in a statement that "we remember [Göncz] with respect as an active and important political player in those years when Hungary stepped on the road from dictatorship to democracy". The coalition partner KDNP added, "Árpád Göncz's personality and life intertwined with Hungary's modern history, the period of [democratic] transition". The left-wing opposition parties, MSZP, Democratic Coalition (DK), Together, Politics Can Be Different (LMP), Dialogue for Hungary (PM) and Hungarian Liberal Party (MLP) also paid tribute to Göncz's political legacy and life, while the far-right Jobbik sent its condolence to his family.[148] On 7 October 2015, thousands gathered for President Göncz at the Kossuth Square, mourning with flowers and candles in front of the Hungarian Parliament Building.[149] On 12 October 2015, Speaker László Kövér said in the next first full plenary session that "the life path of Göncz coincided with major events in Hungary's 20th century history". He added, Göncz, beside his writer and translation career, was also a "loved and respected as a politician as well, and even long after he had left his office in 2000".[150]

Foreign media also remembered on Göncz's death; The New York Times wrote Göncz was "widely beloved" among the Hungarians, who called him just as their "Uncle Árpi".[151] According to The Daily Telegraph, Göncz "worked with skill over a decade to realign his country with the West and heal the wounds of the past."[70] Jean-Claude Juncker, the President of the European Commission said Göncz was a "democrat" and a "true European".[152] During her state visit to Hungary on 7 October, Croatian President Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović expressed condolences for the death of Göncz to President János Áder and the Hungarian people.[153] Socialist MEP István Ujhelyi also commemorated Göncz in the European Parliament. Ujhelyi said "Hungary is mourning one of Europe's wise men and one of the greatest figures of the Hungarian democracy."[154]

In accordance with his last will and testament,[155] Göncz was buried near the graves of his late friends and fellow '56 prisoners, István Bibó, György Litván and Miklós Vásárhelyi at the Óbudai cemetery on 6 November 2015, without official state representation and military honour. The funeral, celebrated by Archabbot Asztrik Várszegi and actor András Bálint, was attended by former and incumbent politicians, representatives of the parliamentary parties and diplomatic missions. Imre Mécs gave the first funeral oration, where he said "Árpi [Göncz] was a man of love, but could also be decisive". Singer Zsuzsa Koncz and composer János Bródy sang their famous song, "Ha én rózsa volnék" ("If I were a rose"). On behalf of the family, Göncz's eldest grandson, political scientist Márton Benedek farewelled his grandfather.[156]

Awards and honours

- 1991: Italy – Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic

- 1991: United Kingdom – Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George

- 1994: Poland – Order of the White Eagle

- 1994: Spain – Collar of the Order of Civil Merit[157]

- 1995: Malta – Honorary Companion of Honour with Collar of the National Order of Merit (9 February 1995)[158]

- 1995: Finland – Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of the White Rose of Finland[159]

- 1999: Estonia – Collar of the Order of the Cross of Terra Mariana

- 1999: Lithuania – Grand Cross of the Order of Vytautas the Great (19 May 1999)[160]

- 1999: Norway – Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St. Olav

- 1999: United Kingdom – Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

- 1999: Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement[161][162]

- 2000: Romania – Grand Cross with Chain of the Order of the Star of Romania (2000)

- 2000: Germany – Special Class of the Grand Cross of the Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

- 2000: Slovakia – Grand Cross (or 1st Class) of the Order of the White Double Cross (2000)[163]

- 2003: Czech Republic – Order of the White Lion (7 March 2003)[164]

- 2003: Award of the Budapest Corvinus Europe Institute

- 2009: International Adalbert Prize for Peace, Freedom and Cooperation in Europe of Adalbert Foundation Krefeld

References

- ↑ "International Advisory Council". Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 24.

- ↑ "Lajos Göncz Bio, Stats and Results". Sport-Reference.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- 1 2 Kim 2012, p. 25.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 26.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 27.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 38.

- ↑ "Lelet: a fiatal Göncz Árpád írása 1938-ból, az első bécsi döntés korából". Heti Válasz. 7 October 2015. Archived from the original on 14 October 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 34.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 33.

- ↑ The Daily Telegraph, Wednesday, 7 October 2015, Obituary [paper only], p.33

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 40.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 42.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 43.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 45.

- 1 2 Kim 2012, p. 48.

- 1 2 3 4 Daily Telegraph, Obit., p.33

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 52.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 53.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 50.

- 1 2 Kim 2012, p. 51.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 78.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 79.

- 1 2 Kim 2012, p. 56.

- 1 2 Kim 2012, p. 58.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 61.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 62.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 63.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 64.

- ↑ "Biszku Béla éjjel vitette el Göncz Árpádot családja mellől" (in Hungarian). Blikk. 7 October 2015. Archived from the original on 13 October 2015. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 65.

- ↑ The Daily Telegraph, Obit., p.33

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 67.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 68.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 70.

- 1 2 3 Kim 2012, p. 73.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 71.

- 1 2 Kim 2012, p. 75.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 76.

- ↑ Arpad Goncz: Steel worker, lawyer, playwright, translator, president of Hungary Archived 18 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine, The Baltimore Sun, Hal Piper, 23 September 1990.

- ↑ A Writer Moves Up, This Time in Hungary, The New York Times, Glenn Collins, 19 May 1990

- ↑ "Göncz Árpád a kollégája betegsége miatt fordíthatta le A Gyűrűk Ura-trilógiát" (in Hungarian). Blikk. 6 October 2015. Archived from the original on 10 October 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ "Göncz Árpád a börtönben lett fordító" (in Hungarian). Origo. 6 October 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ "A regényt fordító Göncz Árpád A Gyűrűk Uráról" (in Hungarian). lfg.hu. 12 January 2002. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ "Műfordítások" (in Hungarian). Göncz Árpád Foundation. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ "Művek" (in Hungarian). Göncz Árpád Foundation. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ "Göncz Árpád emlékezete" (in Hungarian). Népszava. 6 October 2010. Archived from the original on 14 October 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ "A Magyar Írószövetség története" (in Hungarian). Magyar Írószövetség. 6 October 2010. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 101.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 83.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 94.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 97.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 98.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 100.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 85.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 88.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 90.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 92.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 108.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 109.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 111.

- 1 2 "Register". Országgyűlés.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 114.

- 1 2 Kim 2012, p. 120.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 121.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 122.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 195.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 196.

- ↑ "Árpád Göncz, 1st freely elected president, dies aged 93". Budapest Business Journal. 6 October 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Árpád Göncz, Hungarian president – obituary". The Telegraph. 6 October 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ Novak, Benjamin (7 October 2015). "Árpád Göncz, Hungary's first democratically elected president, has died at age 93". The Budapest Beacon. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ "Két Göncz Árpád-idézet, amelyet minden magyar polgárnak meg kéne tanulnia". 6 October 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ "Diana, Princess of Wales". The Telegraph. 31 August 1997. Archived from the original on 10 March 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Prince Charles, Princess Diana visit Hungary". Associated Press News. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ↑ "Épp 20 éve járt nálunk II. Erzsébet királynő". Index.hu. 4 May 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ↑ Out of Russian Orbit, Hungary Gravitates to the West (1997) by Andrew Felkay, pp. 84–5

- ↑ "Árpád Göncz obituary". The Guardian. 7 October 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ Harle, Tamás (22 December 2005). "Magyar szó-vivő a pápa színe előtt". Népszabadság Online. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 129.

- 1 2 Kim 2012, p. 130.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 131.

- 1 2 Kim 2012, p. 132.

- ↑ Sereg, András: Boross – Hadapródiskolától a miniszterelnöki székig. p. 98.

- ↑ "Göncz szerint a taxisblokád idején vissza kellett fogni az elindult a hadsereget" (in Hungarian). Origo. 22 October 2000. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 133.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 134.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 136.

- 1 2 Kim 2012, p. 138.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 140.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 142.

- ↑ 11/1992. (III. 5.) AB határozat, Közzétéve a Magyar Közlöny 1992. évi 23. számában, AB közlöny: I. évf. 3. szám

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 143.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 144.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 147.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 150.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 152.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 154.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 156.

- 1 2 Kim 2012, p. 185.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 186.

- ↑ "Göncz Árpád kifütyülése: közzétették az NBH jelentését". Ma.hu. 30 June 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 187.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 161.

- 1 2 Kim 2012, p. 162.

- 1 2 Kim 2012, p. 163.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 164.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 167.

- 1 2 Kim 2012, p. 169.

- 1 2 Kim 2012, p. 181.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 182.

- ↑ Nohlen, D & Stöver, P (2010) Elections in Europe: A data handbook, p. 899. ISBN 978-3-8329-5609-7

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 190.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 194.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 192.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 231.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 234.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 236.

- ↑ Linda J. Cook & Mitchell A. Orenstein, "The Return of the Left and Its Impact on the Welfare State in Poland, Hungary, and Russia," In: Left Parties and Social Policy in Postcommunist Europe, ed. Linda J. Cook, Mitchell A. Orenstein & Marilyn Rueschemeyer (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1999), p. 91.

- 1 2 Kim 2012, p. 200.

- ↑ Parlament.hu. "1995 presidential election (19 June 1995)". Parlament.hu. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 204.

- 1 2 Kim 2012, p. 206.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 209.

- 1 2 Kim 2012, p. 213.

- 1 2 Kim 2012, p. 218.

- 1 2 Kim 2012, p. 220.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 222.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 224.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 225.

- ↑ "A harmadik körben megválasztották államfőnek Mádl Ferencet". Origo.hu. 4 June 2000. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ↑ "Rezidencia van, csak nem lakható". Index.hu. 16 April 2009. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ "Göncz Árpád a Magyarország Európában Alapítvány elnöke lett". Index.hu. 14 September 2000. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ "Ötvenhat jelzéssé válik". Index.hu. 23 October 2000. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ "Göncz Árpád Budapest díszpolgára lett". Index.hu. 17 November 2000. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ "Albright átadta a Göncz-díjat". Index.hu. 13 December 2000. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ "Medgyessy aláírta". Index.hu. 16 April 2003. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ "Farkasházy Szárszója: ellenzék nélkül". Index.hu. 5 July 2003. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ "Fidel Castro nagyon jól tudja, hogy eljön a nap". Index.hu. 18 September 2003. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ "A nap képe: szerenád Göncz Árpád születésnapja alkalmából". Heti Világgazdaság. 10 February 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ "Schmitt felhívta Gönczöt". Heti Világgazdaság. 10 February 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ "Magyar Családtörténeti Adattár".

- ↑ Ágnes, László (13 August 2013). Erről még nem beszéltem senkinek: Kivételes sorsok, történetek 1989-2009. Kossuth Kiadó. ISBN 9789630976619.

- ↑ "Göncz Árpád: Köszönöm, Magyarország!" (in Hungarian). Origo. 3 August 2000. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ↑ "A Göncz Árpád Alapítvány" (in Hungarian). Göncz Árpád Foundation. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ Arpad Goncz, Hungary's 1st post-communist president, dies

- ↑ Árpád Göncz, Hungarian president – obituary

- ↑ "Meghalt Göncz Árpád – Az Európai Bizottság elnöke igazi európaiként méltatta a volt államfőt". MTI. 6 October 2015. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ↑ "Már életében legenda volt Göncz Árpád". Index.hu. 6 October 2015. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ↑ "Ezrek emlékeztek Göncz Árpádra". Népszava. 7 October 2015. Archived from the original on 14 October 2015. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ↑ "Kövér László: Göncz Árpád sorsa egybeforrt a 20. század magyar történelmével". Híradó.hu. 12 October 2015. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ↑ Fox, Margalit (6 October 2015). "Arpad Goncz, Writer and Hungary's First Post-Communist President, Dies at 93". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ↑ "Juncker: Göncz Árpád igazi európai volt". 168 Óra. 6 October 2015. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ↑ "Nagy egyetértésben beszélt mellé Áder és a horvát államfő". Index.hu. 7 October 2015. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ↑ "Göncz Árpádra emlékeztek Strasbourgban". Népszabadság. 7 October 2015. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ↑ "November 6-án temetik Göncz Árpádot". Index.hu. 13 October 2015. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ↑ "Politikamentes temetésen búcsúztatták Göncz Árpádot". Index.hu. 6 November 2015. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ↑ BOE-A-1994-3535

- ↑ Prime Minister of Malta Website, Honorary Appointments to the National Order of Merit Archived 7 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Suomen Valkoisen Ruusun ritarikunnan suurristin ketjuineen ulkomaalaiset saajat - Ritarikunnat". 9 October 2020.

- ↑ Lithuanian Presidency website, search form Archived 19 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ↑ "Summit Overview Photo". 1999.

His Excellency Árpád Göncz, first President of post-Communist Hungary, addressing the Academy delegates and members at the Hungarian Palace of Justice.

- ↑ Slovak republic website, State honours : 1st Class in 2000 (click on "Holders of the Order of the 1st Class White Double Cross" to see the holders' table)

- ↑ "Göncz cseh állami kitüntetést kap". Index.hu. 6 October 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2003.

Bibliography

- Kim, Dae Soon (2012). Göncz Árpád – Politikai életrajz (in Hungarian). Scolar Kiadó. ISBN 978-963-244-348-5.

- Kim, Dae Soon (2013). The Transition to Democracy in Hungary: Árpád Göncz and the post-Communist Hungarian presidency. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-63664-3.

- The Daily Telegraph, Wednesday, 7 October 2015

- Sodrásban = In mid-stream : talks and speeches by Árpád Göncz. Budapest, Corvina Books, 1999. ISBN 963-13-4801-6

External links

- Official website

- His biography Archived 4 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine on the Office of the President of the Republic of Hungary site

- Árpád Göncz at Find a Grave