The Ålum Runestones are four Viking Age memorial runestones which are located at the church in Ålum, which is 9 km (6 miles) west of Randers, Denmark. One of the stones refers to a man with the title drengr and two of the other stones were raised by the same family.

Ålum 1

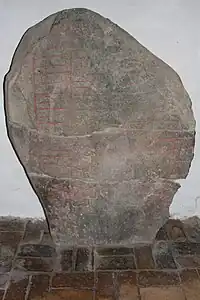

The inscription on Ålum 1, listed as DR 94 in the Rundata catalog, consists of several lines of runic text in the younger futhark on the face of a granite stone 133 cm (52 in) in height. The inscription is classified as being carved in runestone style RAK, which is considered to be the oldest classification. This is the classification for inscriptions where the runic text bands have straight ends without any attached serpent or beast heads. The runestone was discovered in 1843[1] broken into three sections and used in the southeast corner of the church porch.[2] Prior to the understanding of the historic significance of runestones, there were often re-used in the construction of roads, bridges, and buildings such as churches. The sections were removed from the porch in 1879 and reassembled,[2] and is today in the church porch. Part of the original stone is missing, and some of the missing or damaged runic text has been reconstructed based upon similar text from other inscriptions.[2]

The runic text states that a man named Tóli raised the stone in memory of his son Ingialdr, who in the reconstructed text[2] is described in Old Norse as being miok goþan dræng or a "very good valiant man", using the term drengr. A drengr in Denmark was a term mainly associated with members of a warrior group.[3] It has been suggested that drengr along with thegn was first used as a title associated with men from Denmark and Sweden in service to Danish kings,[4] but, from its context in inscriptions, over time became more generalized and was used by groups such as merchants or the crew of a ship.[3] The same Old Norse phrase miok goþan dræng is used on inscription Vg 123 in Västergården to describe the deceased, and several other inscriptions use a variation of the phrase goþan dræng.

Inscription

Transliteration of the runes into Latin characters

- tuli : (r)(i)s-(i) : stin : þasi : aft ¶ ikal:t : sun : sin : miuk (:) (k)¶(u)... ...k : þau : mun(u) ¶ mini : m-(r)gt : ¶ iuf (:) þirta :[5]

Transcription into Old Norse

- Toli res[þ]i sten þæssi æft Ingiald, sun sin, miok go[þan dræn]g. Þø munu minni ... ... ...[5]

Translation in English

- Tóli raised this stone in memory of Ingialdr, his son, a very good valiant man. This memorial will ...[5]

Ålum 2

Ålum 2, listed as DR 95 in the Rundata catalog, is a granite fragment of a runestone that is 69 cm (27 in) in height. It is also classified as being carved in runestone style RAK. The stone was discovered in the northeast foundation of the church nave in 1843, and removed in 1879.[2] Due to the damage and fragmentary condition of the text, although there have been some suggested reconstructions,[2] a proper transcription of the runes into Old Norse has never been accomplished.[6] The stone is today kept in the church porch.

Inscription

Transliteration of the runes into Latin characters

- ...-a * (r)(u)----... ¶ f-(i)(o)... ¶ ...-ta × si ¶ þui × h-...[7]

Ålum 3

The inscription on Ålum 3, listed as DR 96 in the Rundata catalog, consists of runic text in the younger futhark that follows the outline of the stone.[8] The inscription on the gneiss stone, which is 205 cm (81 in) in height, is classified as being carved in runestone style RAK. On the reverse side of the inscription is carved a rider on a horse carrying a shield and a pole and possibly wearing a helmet, although the top of the rider's head has worn away.[2] Several other Scandinavian runestones include depictions of horses, including N 61 in Alstad, Sö 101 in Ramsundsberget, Sö 226 in Norra Stutby, Sö 239 in Häringe, Sö 327 in Göksten, U 375 in Vidbo, U 488 in Harg, U 599 in Hanunda, U 691 in Söderby, U 855 in Böksta, U 901 in Håmö, U 935 at the Uppsala Cathedral, and U 1003 in Frötuna.[9] The Ålum 3 stone was discovered in 1890 at the foot of the church hill,[2] which is considered to be the original location of the stone,[10] and has been erected in the church cemetery.

The runic text states that Ålum 3 was raised by a man named Végautr in memory of his son Ásgeirr. The text ends with a Christian prayer for the soul of his son. The Norse word salu for soul in the prayer was imported from English and is first recorded during the tenth century.[11] Because of the Christian reference and stylistic analysis, the inscription is dated as having been carved after the Jelling stones. The text is related to that of the Ålum 4 stone, which was raised by the wife of Végautr. Both stones are considered to have been carved by the same runemaster.[12]

Inscription

Transliteration of the runes into Latin characters

- : uikutr : risþi : stin : þonsi : iftiʀ : oski : sun : sin : kuþ : hialbi : hons : silu : uil[13]

Transcription into Old Norse

- Wigotr resþi sten þænsi æftiʀ Æsgi, sun sin. Guþ hialpi hans sælu wæl.[13]

Translation in English

- Végautr raised this stone in memory of Ásgeirr, his son. May God well help his soul.[13]

Ålum 4

The inscription on Ålum 4 or DR 97 consists of a text band in the younger futhark that follows the outline of the stone and spirals inward. The inscription is classified as being carved in runestone style RAK. The gneiss stone, which is 150 cm (59 in) in height, was discovered in 1902 in the Ålum church cemetery dike.[14] It was removed from the dike and raised near the Ålum 3 stone in the cemetery. Both DR 96 and DR 97 are considered to have been carved by the same runemaster.[12]

The runic text states that the stone was raised by a woman named Þyrvé, which is often normalized as Thyrve, who was the wife of the Végautr on DR 96.[12] Thyrve was a common name of the period, and a different woman of that name is recorded on the Danish runestone DR 26 in Laeborg and on DR 41 and DR 42 in Jelling, where the woman is commonly known today as Thyra.[15] DR 97 was raised in memory of a man named Þorbjôrn who was the son of Sibbi. The relation between Thyrve and the deceased is described as being systling, which is translated as "cousin," but refers to the child of a close female relative.[14] The text ends with an alliterative text indicating how much she cared for him. Another runestone raised by a woman with a similar alliterative ending to the normal memorial formula is on U 69 in Eggeby.[14]

Inscription

Transliteration of the runes into Latin characters

- þurui : uikuts : kuno : lit : risa : stin : þonsi : eftiʀ : þurbiurn : sun : sibu : sustlik : sin : is : hun : hukþi : b(e)tr : þon : suasum : suni :[16]

Transcription into Old Norse

- Þorwi, Wigots kona, let resa sten þænsi æftiʀ Þorbiorn, sun Sibbu, systling sin, æs hon hugþi bætr þan swasum syni.[16]

Translation in English

- Þyrvé, Végautr's wife, had this stone raised in memory of Þorbjǫrn, son of Sibbi, her cousin, whom she cared for more than had he been her own son / than a dear son.[16]

References

- ↑ "Ålum-sten 1". Danske Runeindskrifter. Danish National Museum. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Wimmer, Ludvig Frands Adalbert; Petersen, Magnus (1901). De Danske Runemindesmaerker Undersøgte og Tolkede af Ludv. F. A. Wimmer (in Danish). Copenhagen: Gyldendal. pp. 191–201, 270–275.

- 1 2 Jesch, Judith (2001). Ships and Men in the Late Viking Age: The Vocabulary of Runic Inscriptions and Skaldic Verse. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. pp. 219, 229–31. ISBN 978-0-85115-826-6.

- ↑ Sawyer, Birgit (2000). The Viking-Age Rune-Stones: Custom and Commemoration in Early Medieval Scandinavia. Oxford University Press. pp. 103–107. ISBN 0-19-820643-7.

- 1 2 3 Project Samnordisk Runtextdatabas Svensk - Rundata entry for DR 94.

- ↑ "Ålum-sten 2". Danske Runeindskrifter. Danish National Museum. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- ↑ Project Samnordisk Runtextdatabas Svensk - Rundata entry for DR 95.

- ↑ Fuglesang, Signe Horn (1998). "Swedish Runestones of the Eleventh Century: Ornament and Dating". In Düwel, Klaus (ed.). Runeninschriften als Quellen interdisziplinärer Forschung. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 197–218. ISBN 3-11-015455-2. p. 199.

- ↑ Oehrl, Sigmund (2010). Vierbeinerdarstellungen auf Schwedischen Runensteinen: Studien zur Nord Germanischen Tier- und Fesselungsikonografie (in German). Walter de Gruyter. p. 33. ISBN 978-3-11-022742-0.

- ↑ "Ålum-sten 3". Danske Runeindskrifter. Danish National Museum. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- ↑ Spurkland, Terje (2005). Norwegian Runes and Runic Inscriptions. van der Hoek, Betsy (transl.). Woodbridge: Boydell Press. pp. 133–135. ISBN 1-84383-186-4.

- 1 2 3 Moltke, Erik; Jacobsen, Lis Rubin (1942). Danmarks Runeindskrifter (in Danish). Munksgaard. p. 962.

- 1 2 3 Project Samnordisk Runtextdatabas Svensk - Rundata entry for DR 96.

- 1 2 3 "Ålum-sten 4". Danske Runeindskrifter. Danish National Museum. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- ↑ Jesch, Judith (1991). Women in the Viking Age. Boydell & Brewer. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-85115-360-5.

- 1 2 3 Project Samnordisk Runtextdatabas Svensk - Rundata entry for DR 97.