Đeram

Ђерам | |

|---|---|

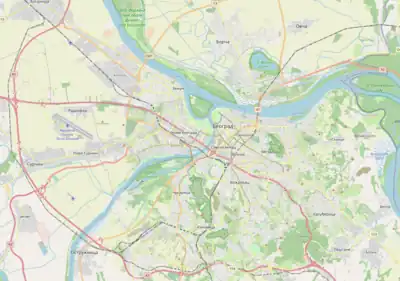

Đeram Location within Belgrade | |

| Coordinates: 44°48′05″N 20°29′14″E / 44.80139°N 20.48722°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Belgrade |

| Municipality | Zvezdara |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Area code | +381(0)11 |

| Car plates | BG |

Stari Đeram, colloquially Đeram (Serbian: Стари Ђерам), is an open greenmarket and an urban neighborhood of Belgrade, the capital of Serbia. It is located in Belgrade's municipality of Zvezdara.

Location

Đeram is located along Bulevar kralja Aleksandra, centered on the open greenmarket of the same name, in the eastern section of Zvezdara municipality, 2 km (1.2 mi) south-east of downtown Belgrade (Terazije). It borders the neighborhood of Crveni Krst on the south, Lipov Lad on the south-east, Lion on the east, Bulbuder and Slavujev Venac on the north and Vukov Spomenik on the west.[1][2]

Administration

When Belgrade was divided into municipalities in 1952, a municipality of Stari Đeram (Old Đeram) was created. On 1 January 1957, that municipality was abolished and merged with Zvezdara. The neighborhood was later organized as two local communities (sub-municipal administrative unit), Stari Đeram and Smederevski Đeram (Smederevo Đeram). Stari Đeram was annexed to the local community of Vukov Spomenik in the 1980s.

Population

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1981 | 5,524 | — |

| 1991 | 4,956 | −10.3% |

| 2002 | 2,465 | −50.3% |

| 2011 | 3,133 | +27.1% |

| Source: [3][4][5][6] | ||

The municipality of Stari Đeram had a population of 27,595 by the 1953 census.[7] Prior to becoming part of the Vukov Spomenik, local community Stari Đeram had a population of 4,488 in 1981. The remaining local community of Smederevski Đeram, which occupies much smaller area that the former municipality, had a population of 3,133 by the 2011 census.

Đeram Greenmarket

The main feature of the neighborhood is one of Belgrade's largest open greenmarkets, Đeram pijaca. In 1821, the state government decided to put the food trade in order and to establish the quantity and quality of the goods imported to the city. Part of the project was introduction of the excise on the goods (in Serbian called trošarina) and setting of a series of excise check points on the roads leading to the city. One of those check points, which all gradually also became known as trošarina, was on the Tsarigrad Road, later renamed Smederevo Road (modern Bulevar Kralja Aleksandra). As it had a ramp, it resembled the đeram, a cattle-drawn water well with a ramp, so it was named after it. As the name of the street was changed later, it became known as Smederevo Đeram. Gradually, an open greenmarket formed around it.[8] It was to be renovated in 2008 and to become the first covered green market of that size in Belgrade. Though the project was not scrapped, as of October 2017 the reconstruction is still pending.

Apart from that, the neighborhood is mainly residential with a strong commercial section along the boulevard, one of the main shopping areas in Belgrade.

References

- ↑ Tamara Marinković-Radošević (2007). Beograd - plan i vodič. Belgrade: Geokarta. ISBN 86-459-0006-8.

- ↑ Beograd - plan grada. Smedrevska Palanka: M@gic M@p. 2006. ISBN 86-83501-53-1.

- ↑ Osnovni skupovi stanovništva u zemlji – SFRJ, SR i SAP, opštine i mesne zajednice 31.03.1981, tabela 191. Savezni zavod za statistiku (txt file). 1983.

- ↑ Stanovništvo prema migracionim obeležjima – SFRJ, SR i SAP, opštine i mesne zajednice 31.03.1991, tabela 018. Savezni zavod za statistiku (txt file).

- ↑ Popis stanovništva po mesnim zajednicama, Saopštenje 40/2002, page 4. Zavod za informatiku i statistiku grada Beograda. 26 July 2002.

- ↑ Stanovništvo po opštinama i mesnim zajednicama, Popis 2011. Grad Beograd – Sektor statistike (xls file). 23 April 2015.

- ↑ Popis stanovništva 1953, Stanovništvo po narodnosti (pdf). Savezni zavod za statistiku, Beograd.

- ↑ Dragan Perić (22 October 2017), "Beogradski vremeplov - Pijace: mesto gde grad hrani selo" [Belgrade chronicles - greenmarkets: a place where village feeds the city], Politika-Magazin, No. 1047 (in Serbian), pp. 26–27