"f/8 and be there" is an expression popularly used by photographers to indicate the importance of taking the opportunity for a picture rather than being too concerned about using the best technique. Often attributed to the noir-style New York City photographer Weegee, it has come to represent a philosophy in which, on occasion, action is more important than reflection.

Background

Before digital photography, in what Kathy Day called the "heyday of photojournalism, before auto-focus and pixels",[2] spot photography (known to contemporaries as "moment photography") was popular. This attempted to epitomise an entire visual story through a single photograph taken either as the event was occurring or immediately after. Situations that lent themselves particularly well to this approach were criminal activity (particularly that of the Mafia and organised crime) and accidents and car crashes.[3]

Weegee

The expression has been attributed—probably apocryphally—to the American photographer Arthur Fellig, more popularly known as Weegee,[note 1] who has been described as "the famous spot news photographer of the mid-20th century".[3] Known for stark black and white[5]—"searing chiaroscuro"[6]—photography, Weegee used a "big, flash-popping Speed Graphic"[4] although Terry Teachout has suggested that he probably used ƒ/16, that being the lowest aperture in general use.[7][note 2]

Philosophy

The philosophy has been explained thus:

Simplicity in the technical is equal to being present and prepared. No complicated photographic technique here: just a basic setting (ƒ/8) with enough depth of field for most subjects. And then "being there" in the right place, right time, tuned in to your surroundings, ready to shoot the perfect moment when it unfolds in front of your lens.[9][note 3]

— Rich Underwood

Effectively it emphasises less reliance on high technology and more reliance on average settings and personal skill,[11] as well as portraying the story accurately and graphically.[12]

It is akin, says the photographer Douglas Peebles, in its simplicity and obviousness to the advice "if you want to be famous for photographing famous people, begin by photographing famous people".[13] It is being there, said "that predisposes luck in the photographer's favour".[14] The Encyclopedia of International Media and Communications has suggested that while the "ƒ/8 and be there" tactic was sensationalist, it was also, by the same token, more likely to win the photographer awards.[3]

It epitomises the popularity of lurid newspaper reports which were giving tabloids extremely large circulations and also how journalism was increasingly being influenced by the theatrics of Hollywood.[15] The photography author Ken Kobre has summed it up as "check human tragedy first. Concentrate on the human element of any tragedy. Readers relate to people pictures."[3]

Specs

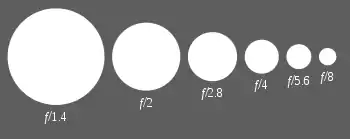

ƒ/8 is considered in photography to be a general-purpose aperture ("that never fails", commented the magazine editor Richard Stolley in 2009).[16] With the aperture set to ƒ/8 (allowing sufficient light to enter for exposure but not so much as to bleach the picture)[12] and the lens set to the hyperfocal distance—which results in a sharply-focussed depth of field whether taking pictures up close or at great distances.[17][note 4] ƒ/8 allows sufficient depth of field and lens speed for good, clear exposure in most daylight situations.[18]

Cultural touchstone

The expression, wrote Michigan Daily photojournalist Andy Sacks, summed up "everything a successful news photographer needed to know".[19] It has been particularly advocated for street and outdoor photography,[20] particularly mountain stereography[2] and wildlife.[21] It has also become a mantra for non-photography disciplines and hobbies, for example self-help philosophies.[22]

Notes

- ↑ "Weegee" may be a phonetic spelling of ouija, a type of board used for fortune-telling—suggesting Weegee's prescience in reaching crime scenes[4]

- ↑ Weegee himself described the origins of his work thus: "In my particular case I didn't wait 'til somebody gave me a job or something, I went and created a job for myself—freelance photographer. And what I did, anybody else can do. What I did simply was this: I went down to Manhattan Police Headquarters and for two years I worked without a police card or any kind of credentials. When a story came over a police teletype, I would go to it. The idea was I sold the pictures to the newspapers. And naturally, I picked a story that meant something".[8]

- ↑ Although fundamental to a great picture, argues Howard Chapnick, it is not in itself enough; after all, he hypothesized, "why is it that photographers covering the same event produce pictures of varying and dramatically different quality?"[10]

- ↑ Indeed, it has been suggested that, once his settings were so loaded, "a photographer of 40 years ago could still get off a shot faster today than someone using a point-and-shoot digital camera or all but the best digital SLRs."[17]

References

- ↑ "Weegee's Speed Graphic camera". International Center of Photography. 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2023-04-20.

- 1 2 Day 2004, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 4 Perlmutter 2003.

- 1 2 CEE 2019.

- ↑ Hudson 2009, p. 1060.

- ↑ Spicer & Hanson 2003, p. 185.

- ↑ Teachout 2018, p. 74.

- ↑ Bomb 1980, p. 58.

- ↑ Underwood 2007.

- ↑ Chapnick 1994, p. 346.

- ↑ Galer 2015, p. 167.

- 1 2 Koltermann 2017, p. 55.

- ↑ Peebles 2011, p. 13.

- ↑ Proceedings 1976, p. 309.

- ↑ Pelizzon & West 2004, p. 25.

- ↑ Stolley 2009, p. ix.

- 1 2 Simon 2004, p. 24.

- ↑ Levy 2001, p. 163.

- ↑ Sacks 2015, p. 13.

- ↑ Leonard 2017, p. 25.

- ↑ Tanner 2018.

- ↑ Phillips 2001, p. 206.

Sources

- Bomb (1980). "Weegee on Weegee". Bomb Magazine (20).

- CEE (2019). Weegee.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|website=ignored (help) - Chapnick, H. (1994). Truth Needs No Ally: Inside Photojournalism. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-82620-955-9.

- Day, K. (December 2004). "F11 and Be There". Stereoscopy: The Journal of the International Stereoscopic Union (60): 5–11. OCLC 1068820667.

- Galer, M. (2015). Introduction to Photography: A Visual Guide to the Essential Skills of Photography and Lightroom. London: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-31752-087-0.

- Hudson, B. (2009). Sterling, C. H. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Journalism. Vol. IV. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. pp. 1060–1067. ISBN 978-0-76192-957-4.

- Koltermann, F. (2017). Fotoreporter im Konflikt: Der internationale Fotojournalismus in Israel/Palästina. Bielefeld: Verlag. ISBN 978-3-83943-694-3.

- Leonard, B. (2017). The Great Outdoors: A User's Guide: Everything You Need to Know Before Heading into the Wild (and How to Get Back in One Piece). New York, NY: Artisan. ISBN 978-1-57965-782-6.

- Levy, Michael (2001). Selecting and Using Classic Cameras: A User's Guide to Evaluating Features, Condition & Usability of Classic Cameras. Amherst Media, Inc. ISBN 978-1-58428-054-5.

- Peebles, D. (2011). Photographing Maui: Where to Find Perfect Shots and How to Take Them. Woodstock, VT: Countryman Press. ISBN 978-1-58157-893-5.

- Pelizzon, V. P.; West, N. M. (2004). ""Good Stories" from the Mean Streets: Weegee and Hard-Boiled Autobiography". The Yale Journal of Criticism. 17: 20–50. doi:10.1353/yale.2004.0006. S2CID 162223641.

- Perlmutter, D. D. (2003). Photojournalism (Still News Photography). Elsevier Science & Technology. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|website=ignored (help) - Phillips, N. (2001). The Big Difference: Life Works when You Choose it. Harlow: Pearson. ISBN 978-1-84304-001-9.

- Proceedings (1976). "Jim's father was a news photographer In Milwaukee". Technical Communication. 23.

- Sacks, A. (2015). "ƒ/8 and be there". In Steinberg, S. (ed.). In the Name of Editorial Freedom: 125 Years at the Michigan Daily. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. pp. 12–14. ISBN 978-0-47203-637-0.

- Simon, D. (2004). Digital Photography Bible. London: John Wiley. ISBN 978-0-76457-658-4.

- Spicer, A.; Hanson, H. (2003). A Companion to Film Noir. London: John Wiley. p. 185. ISBN 978-1-11852-371-1.

- Tanner, K. (2018). "On his way to go surfing in Morro Bay, this photographer captured a 'melee' of wildlife". The Tribune. Archived from the original on 20 April 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- Cookman, C. H.; Stolley, R. B. (2009). "Foreword". American Photojournalism: Motivations and Meanings. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. pp. ix xiv. ISBN 978-0-81012-358-8.

- Teachout, Terry (2018). "The Lost World of Weegee". Commentary Magazine: 73 76.

- Underwood, R. (2007). Roll! Shooting TV News: Views from Behind the Lens. New York: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-13603-329-2.