| 1886 World Series | |

|---|---|

NL: Chicago White Stockings (2–4) | |

AA: St. Louis Browns (4–2) | |

«1885 1887» |

The 1886 World Series was won by the St. Louis Browns (later the Cardinals) of the American Association over the Chicago White Stockings (later the Cubs) of the National League, four games to two. The series was played on six consecutive days running from October 18 to October 23 in Chicago and St. Louis.

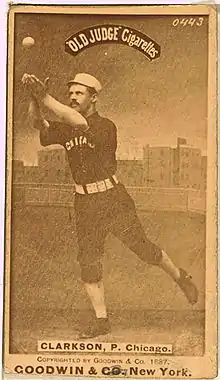

The teams were judged to be approximately equal going into the series, with gamblers betting on the teams at even odds. However, Chicago pitcher Jim McCormick was sidelined by a chronic foot ailment after game 2, and third Chicago pitcher Jocko Flynn had already been lost for the season due to an arm ailment. An effort to use a substitute pitcher was protested by St. Louis, with the board of umpires flipping a coin to decide the matter in favor of the Browns. With his team unable to field a competent second starter, Chicagos ace John Clarkson proved unable to carry the full pitching load, tipping the series to St. Louis.

The series was decided in extra innings of game 6 by Curt Welch's so-called "$15,000 slide" following a passed ball. The decisive run scored by Welch became one of the most famous plays in the history of baseball in that era.

Background

In 1886, the St. Louis Browns won the American Association championship for the second consecutive season with a record of 93–46, while the Chicago White Stockings[1] won the National League championship with a record of 90–34.[2] The victory for the White Stockings, who featured the 6 ft 2 in (1.88 m) slugger Cap Anson, marked the 6th time in 11 years that the team had garnered the National League pennant.[2]

The two teams agreed to meet each other in a best-of-seven pre-modern-era World Series, with the winner taking all the prize money.[3][4] It was the second straight year that the Browns and White Stockings met in the World Series.[5] The six games of the series were played on six consecutive days.[6] The first three games were scheduled for Chicago, with the next three games to be held in St. Louis.[2] A decisive seventh game, if necessary, was to be held in a neutral site.[2] The location of the rubber game in the match was to be determined by coin toss, with each franchise owner selecting a city for the game.[7]

Going into the series, gamblers are said to have assessed the teams as approximately equal, with bets on the series outcome commonly taking place at even money.[8] More than $50,000 was said to have been wagered on the series in St. Louis alone.[9] The Browns are said to have traveled together on a special rail car to Chicago on the day before the scheduled October 18 start of the series.[9]

Game summaries

Game 1

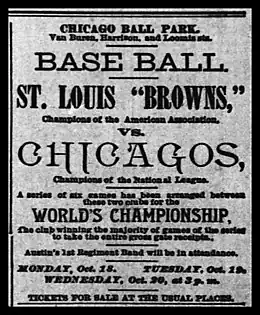

Monday, October 18, 1886 at Chicago Ball Park in Chicago, Illinois

| Team | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | R | H | E | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| St. Louis Browns | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 6 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Chicagos | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | X | 6 | 9 | 5 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| WP: John Clarkson (1–0) LP: Dave Foutz (0–1) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

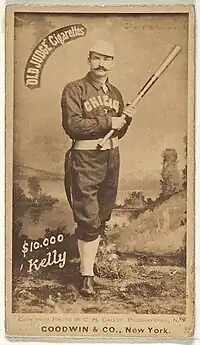

The Browns arrived in Chicago on the morning of game day, October 18, and were immediately incensed at an article appearing in the morning Chicago Tribune calling Browns' star third baseman Arlie Latham a "monkey" and advising that White Stockings outfielder King Kelly should create a collision with him on the base.[7] The series started in cold, windy conditions[10] at 3:00 pm, with the grandstands filled with a crowd estimated variously between 3,000[7] and 5,000[11] — somewhat fewer than anticipated.[7]

The game began with a coin toss to determine which side would bat first, with Anson and Chicago winning the call and sending the Browns to the plate to open.[11]

After retiring the side in order in the top of the first, Chicago quickly jumped out to a two-run lead powered by a Cap Anson RBI triple to the right-center gap.[11] Clean-up hitter Fred Pfeffer drove Anson home with a single, and the blue-uniformed home team took a lead, 2–0.[11] This would prove to be all the scoring that the White Stockings needed for the win as Chicago's ace pitcher John Clarkson (a future member of the Baseball Hall of Fame) struck out ten[12] in throwing a five-hit shutout as "Anson's Pets" beat Dave Foutz and the Browns, 6–0.[5]

Game 2

Tuesday, October 19, 1886 at Chicago Ball Park in Chicago, Illinois

| Team | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | R | H | E | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chicagos | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 12 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| St. Louis Browns | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 12 | 11 | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

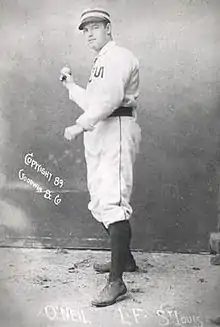

| WP: Bob Caruthers (1–0) LP: Jim McCormick (0–1) Home runs: CHI: None STL: O'Neill (1, 2) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Scottish-born right-hander Jim McCormick got the start and took the loss for Chicago, giving up two home runs to St. Louis outfielder Tip O'Neill.[5] St. Louis curveball specialist Bob Caruthers made short work of the home team, allowing just two hits and cruising to a 12–0 victory in a game mercifully shortened to 8 innings by darkness.[13]

The game was reckoned by one sportswriter to be "one of the worst games...ever played" by the Chicagos, who not only failed to hit Caruthers but who also "fielded like a parcel of schoolboys out on a lark and missed nearly every opportunity given them to do effective work."[13] Chicago committed an astounding 12 errors and made 2 wild pitches in the defeat, with third baseman Tom Burns single-handedly adding 4 errors to the team total.[13]

Game 3

Wednesday, October 20, 1886 at Chicago Ball Park in Chicago, Illinois

| Team | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | R | H | E | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chicagos | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 11 | 12 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| St. Louis Browns | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 9 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| WP: John Clarkson (2–0) LP: Bob Caruthers (1–1) Home runs: CHI: Kelly (1), Gore (1) STL: None | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Heavy morning rain in Chicago followed by extensive drizzle threatened the third game of the 1886 World Series on October 20.[14] However, around 2:00 pm the skies cleared up and the ground was fit to play when the teams took the field for warmups shortly before 3:00 pm.[14] Attendance was weak, doubtlessly owing to the bad weather.[14] Coming off his complete game 1-hitter the previous day, Bob Caruthers again took the ball for the Browns, while John Clarkson made his second series start for the White Stockings.[14] A coin toss determined the first team to bat, with St. Louis winning the flip and sending Chicago up to the plate first.[14]

With his effectiveness hindered by the necessity of pitching two days in a row, the Browns found themselves on their heels quickly when ace Bob Caruthers walked four of the first five batters, surrendering a second run on a base hit given up to third baseman Tom Burns of the Chicagos.[12] The game was called after completion of eight innings due to darkness. John Clarkson was again on top of his game as the right hander struck out 8 Browns in earning his second win of the series.[12] Caruthers took the loss for the Browns, giving Chicago a lead of two games to one in the series.[3][6]

The Browns and their supporters were despondent over the loss and returned from Chicago to a station devoid of welcoming fans.[12] Browns players were critical of player-manager Charlie Comiskey's decision to start Caruthers in back-to-back games, noting that Nat Hudson had been ready to start for the visitors until the last-minute decision was made to bring back the team's ace on zero rest.[12] Star outfielder Tip O'Neill expressed the view that the pitching situation had been miserably managed and that the entire team had been put off by the decision not to rest Caruthers.[12]

Gambling odds to win the series moved to 5:4 in favor of Chicago following the Browns' game 3 loss.[12]

Game 4

Thursday, October 21, 1886 at Sportsman's Park in St. Louis, Missouri

| Team | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | R | H | E | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chicagos | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 9 | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| St. Louis Browns | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 3 | X | 8 | 10 | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| WP: Dave Foutz (1-1) LP: John Clarkson (2-1) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The series moved to St. Louis on October 21, with Chicago ace John Clarkson pitching for the third time in four days.[15] Clarkson was nothing if not durable, having won 53 games in 1885 to lead the National League — the second greatest number of wins by an individual pitcher in baseball history.[16] It was necessity rather than design that forced Clarkson into back-to-back action during the World Series, however. Chicago's second pitcher, Jim McCormick, failed to make the trip due to a recurrence of "rheumatism" in his feet, an ailment which hampered his mobility and made participation impossible.[12] Moreover, third Chicago pitcher Jocko Flynn, a 23-game winner, was already lost to the team for the year (and for his career) with arm trouble.[17] In an effort to overcome the pitching deficit the team hurriedly signed a youthful 39-game winner from a minor league club in Duluth, Ward Baldwin,[12] but the new addition to the team did not see action in the series.

It was not for the lack of trying that Baldwin was unavailable to fill the void left by McCormick's injury. Chicago manager Cap Anson intended to start the newcomer in game 4, but objection was made by Browns owner Chris von der Ahe, who declared there was an understanding that the World Series was a competition between the two teams which had won the championships of their respective leagues and that no additional players were to be used by either side.[17] Chicago owner Albert Spalding remonstrated on behalf of the new addition to his stable and the two owners stormed off for speedy decision of the dispute by the board of umpires appointed for the series, a process specified by an earlier agreement between the teams.[17] Three of the four umpires (two from each league) were located and it was determined that the matter should be left to the toss of a coin.[17] The National League lost the flip and Baldwin was barred from the series.[17]

After the starting bell rang at 3:15 pm, the Chicagos managed to rack up a 3–0 lead in the top of the first inning with one hit, two walks, two errors, and a sacrifice fly.[18] The Browns narrowed the margin with a run in the second inning on some astute base running by Bill Gleason, with another run notched in the third inning when Tip O'Neill tripled home a runner.[18] The tide turned decisively in the fifth inning when starting pitcher John Clarkson, pitching a second consecutive game, began to run out of gas, giving up a two-run single to center by Gleason, followed by an RBI single by Browns first baseman Charlie Comiskey.[18]

The White Stockings managed to get two runs back in the top in the sixth, powered by Abner Dalrymple's RBI triple to right field, followed by a base hit by Clarkson.[18] The Browns put the game away for good with three more runs in the bottom half of the frame, however, with three walks, two singles, and a muffed fly ball doing the damage.[18] The game was called after seven innings due to darkness, the series knotted at two games each. Chicago manager Cap Anson was angered by the decision to call the game after 7 innings, claiming that sufficient light remained to see the ball when the game was ended, but his plea went unheeded as the crowd of about 8,000 scurried for the exits.[18]

After the game losing pitcher John Clarkson acknowledged that "They got away with me today, without the shadow of a doubt. I can't say anything, but they beat us all around.... They just hit me and hit me hard."[18] While losing pitcher Clarkson was sanguine about the defeat, team owner Spalding was enraged by the outcome, declaring to a newspaper reporter that his team had "a perfect right" to pitch new signee Ward Baldwin instead of the exhausted Clarkson and that the St. Louis owner "had no business to interfere with me."[18] He continued:

"Baldwin is as much a member of the Chicago Club as any man on it and we signed him for the season of 1886 (sic.) and 1887 as well. I am not at all satisfied with the result of today's business, and I think the action of Mr. Von der Ahe in the matter was unsportsmanlike and wrong, and if the loss of this game interferes with our winning the series, I think it would be only right to make some kind of a protest against it."[18]

Game 5

Friday, October 22, 1886 at Sportsman's Park in St. Louis, Missouri

| Team | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | R | H | E | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chicagos | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| St. Louis Browns | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 | X | 10 | 11 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| WP: Nat Hudson (1-0) LP: Ned Williamson (0-1) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The action returned to St. Louis on October 22 for game 5. Chicago manager Cap Anson attempted to start the game with Ned Baldwin in the pitcher's area, but the St. Louis crowd roared its disapproval and the Browns refused to play until Baldwin was removed.[19] Forced to improvise in light of Chicago's lack of an alternate pitcher to John Clarkson, Anson trotted out shortstop Ned Williamson to make the start, only to see the hapless conscript knocked out of the box after giving up three hits and walk in the first inning, resulting in two runs. Right fielder Jimmy Ryan came in to relieve, showing himself a better pitcher than Williamson but nevertheless taking the loss as his teammates blundered away the game defensively.

One observer noted that "the playing on both sides was very loose, the batting heavy, and the errors numerous," with the Chicagos playing a particularly "wretched game both at the bat and in the field."[20] Chicago right fielder Tom Burns committed two particularly costly errors, allowing runs to score, with Nat Hudson giving up only three hits en route to an easy 10–3 victory.[20] Catcher Silver Flint contributed mightily to the carnage, allowing four runs to score on passed balls and making another costly throwing error to third base.[20]

The game was called after 7 innings when it became too dark to see the ball.[20] An estimated 16,000 fans were in attendance to witness the hometown Browns go up three games to two in the best-of-seven series.[20]

Game 6

Saturday, October 23, 1886 at Sportsman's Park in St. Louis, Missouri

| Team | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | R | H | E | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chicagos | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| St. Louis Browns | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| WP: Bob Caruthers (2-1) LP: John Clarkson (2-2) Home runs: CHI: Pfeffer (1) STL: None | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The final game of the 1886 World Series took place in St. Louis on October 23 and proved to be a legendary affair. Bob Caruthers made his third pitching start for St. Louis, with John Clarkson returning to the mound for a fourth time for Chicago. Under threatening skies the White Stockings took a 2–0 lead into the fourth inning, when a brief rain shower prompted fans to leave the grandstand and run onto the field, demanding that the umpire call the game, thereby nullifying the result, because of inclement weather.[21] Order was restored only with the assistance of a legion of police.[21]

A 3–0 Chicago lead held until a dramatic eighth-inning comeback by the Browns. Charlie Comiskey began the St. Louis half of the inning with a single to right field and was sent to third by a bunting Curt Welch, who managed to beat out the throw to first base, putting runners on the corners.[22] Chicago infielder Tom Burns threw wildly to first in an effort to pick off Welch only to see the ball skip away and Comiskey score on the error, with Welch advancing to second.[22] The home crowd erupted.[22] Clarkson managed to collect two outs when Dave Foutz and Yank Robinson flew out, but he kept the inning alive with a walk of the hitter in the 9-spot, Doc Bushong, bringing the potential go-ahead run to the plate, leadoff hitting third baseman Arlie Latham.[22]

The loud and abrasive Cap Anson had been riding Latham throughout the game when he was on the field from the third base coaching area, taunting him as a "soft spot" in the Browns' defense.[22] Latham delivered his answer with his bat, hammering a long fly ball that was misjudged by outfielder Abner Dalrymple.[22] Running on contact, both Welch and Bushong scored on the play, knotting the score at 3.[22]

Neither team scored in the 9th inning, sending the game to extra innings.[22] Chicago similarly failed to score in their half of the 10th inning, but in the bottom half of the frame the Browns started a rally, with the Browns' Curt Welch advancing to third base. Clarkson wound up and threw a pitch that got past catcher King Kelly, with Welch coming home to win the game and the series for St. Louis. It is disputed whether or not Welch was forced to slide in scoring the winning run, but the event was memorialized as the "$15,000 Slide" nevertheless and became the most famous play in 19th century baseball.[23]

There was contemporary disagreement as to whether the final play of the game was made possible by a passed ball or a wild pitch, with Chicago catcher King Kelly telling the press that he was willing to take the blame:

"I signaled Clarkson for a low ball on one side and when it came it was high up on the other. It struck my hand as I tried to get it, and I would say it was a passed ball. You can give it to me if you want to. Clarkson told me that it slipped from his hands."[24]

The reporter of the Chicago Tribune differed with the official scoring decision, asserting that the all-important passed ball was "really a wild pitch by Clarkson."[21]

Regardless of the intricacies of official scoring, the winning run excited the packed grandstand mightily, with fans remaining in their seats and cheering for fifteen minutes after the game was over, while hundreds of others stormed the Browns' locker room with congratulations.[21]

Overview

The Browns' Tip O'Neill led all players with a .400 batting average, eight hits, and two home runs in the series.[4] Welch had the second-highest batting average, at .350.[4] Caruthers, who started three games for St. Louis, went 2–1 with a 2.42 earned run average.[4] Clarkson started four games for Chicago and went 2–2 with a 2.03 ERA.[4]

The Browns outhit the White Stockings in the series, scoring a total of 38 runs in the six games to 28 for their National League opponents.[25] The Browns amassed a total of 64 hits, including 6 doubles, 8 triples, and 2 homers against a total of 52 hits for the White Stockings, who managed 13 extra-base hits, including 3 home runs.[25]

It was agreed before the series that one half of total gate receipts would be distributed among the players, with the victors receiving the spoils on a winner-takes-all basis. All receipts were put into the bank in a joint account held by the team owners, with no disbursal of funds to take place until one team had won a majority of games in the 7-game series.[18] A similar winner-takes-all allocation of the other half of the proceeds was made by the respective teams' owners.[18] Total receipts for the series were $13,920.10, from which was first deducted the $100 salaries of the umpires and team travel expenses.[24] The remaining funds were split in half between Browns players and team owner Chris Von der Ahe, with each player taking home slightly over $500.[24]

The 1886 World Series was the American Association's only undisputed championship over the National League.[6]

Batting order

|

St. Louis Browns |

Chicago White Stockings |

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Despite the seeming similarity of names the Chicago White Stockings were actually the precursor of the Chicago Cubs, not the Chicago White Sox.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Pennant Won: Chicago Takes Off the Honors of the National League," Greensboro North State, Oct. 14, 1886, pg. 5.

- 1 2 "The Chronology – 1886" Archived 2007-10-17 at the Wayback Machine. baseballlibrary.com. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "1886 World Series". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- 1 2 3 John Snyder, Cardinals Journal. Clerisy Press, 2013; pp. 34–35.

- 1 2 3 David Nemec, The Beer and Whisky League. Globe Pequot, 2004; pp. 6, 118–120.

- 1 2 3 4 "Anson's Pets Down Our Browns in Series," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, vol. 37, no. 92 (Oct. 18, 1886), pg. 1.

- ↑ "Even Money: All the Chicagoans Will Bet on Their Pets Today," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, vol. 37, no. 92 (Oct. 18, 1886), pg. 7.

- 1 2 "Off for Chicago," The Tennessean [Nashville], Oct. 18, 1886, pg. 8.

- ↑ Albert John Bushong, "'Doc's' Dictim: Bushong Explains Yesterday's Defeat in Chicago," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, vol. 37, no. 93 (Oct. 19, 1886), pg. 7.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Browns Massacred: Anson's Men Wipe Up the Earth with the Pets," Chicago Tribune, Oct. 19, 1886, pg. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Home Again: The Browns Arrive from the City by the Lake This Morning," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Oct. 21, 1886, pg. 8.

- 1 2 3 "What Can the Matter Be? The 'World Beaters' Maul the 'Champs' to the Tune of 12 to 0," Detroit Free Press, Oct. 20, 1886, pg. 8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Under Clear Skies: The Browns Meet the Chicago 'Fat Boy' Nine Again," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, vol. 37, no. 94 (Oct. 20, 1886), pg. 1.

- ↑ Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010; pg. 47.

- ↑ "Single Season Leaders and Records for Wins," Baseball-Reference.com, www.baseball-reference.com/

- 1 2 3 4 5 "A Big Stake: What the Chicago and St. Louis Clubs Are Playing For," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Oct. 23, 1886, pg. 8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "'That's the Way!' Capt. Anson's Babies Have Nothing to Say About Their Defeat," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Oct. 22, 1886, pg. 5.

- ↑ "The World's Championship: The St. Louis Browns Defeat the Chicagos and are One Game Ahead," Washington Evening Star, Oct. 23, 1886, pg. 8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "St. Louis One Ahead: The Browns Win the Fifth World's Championship Game," Philadelphia Times, Oct. 23, 1886, pg. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 "Browns the Champions: Anson's Men Defeated by Von der Ahe's Pets," Chicago Tribune, Oct. 24, 1886, pg. 10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 The Sporting News, December 31, 1898, reproduced in Dennis Pajot, "Baseball's First World Series Goat," Seamheads.com, April 6, 2009.

- ↑ "The 1886 World Series: Breaking Down the $15,000 Slide," This Game of Games, www.thisgameofgames.com/ Aug. 17, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "The World's Champions: Friends of the Browns Will Banquet Them Next Saturday Night," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Oct. 25, 1886, pg. 5.

- 1 2 "They Never Lie: Figures in the Case of the League vs. the Association," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Oct. 30, 1886, pg. 10.

Further reading

- Jon David Cash, Before They Were Cardinals: Major League Baseball in Nineteenth-Century St. Louis. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2002.

- Dennis Pajot, "Baseball's First World Series Goat: Abner Dalrymple and Game Six of the 1886 World Series," Seamheads.com, April 6, 2009.

- Bob Tiemann, "October 23, 1886: Curt Welch's Winning Slide," Society for American Baseball Research, www.sabr.org/

- Robert L. Tiemann and Mark Rucker (eds.), Nineteenth Century Stars: 2012 Edition. Society for American Baseball Research, 2012.

External links

- "1886 World Series: Batting and Pitching Statistics," Baseball-Reference.com, www.baseball-reference.com/

- "The 1886 World Series," This Game of Games: St. Louis Baseball in the 19th Century, www.thisgameofgames.com/