The 1912 Brisbane General Strike in Queensland, Australia, began when members of the Australian Tramway and Motor Omnibus Employees' Association were dismissed when they wore union badges to work on 18 January 1912. They then marched to Brisbane Trades Hall where a meeting was held, with a mass protest meeting of 10,000 people held that night in Market Square (also known as Albert Square, now King George Square).

General Strike

The Brisbane Tramways were owned by the Brisbane Tramway Company a mainly local owned company linked with the former Metropolitan Tramway and Investment Company horse tramway company and the Melbourne Tramway and Omnibus Company but operated it as an English Company as the main investors - in Melbourne and Brisbane as well as England and Scotland - owned tramways on all continents, however, there were a number of inter-related companies all with Brisbane Tramways in the title.[1][2][3][4] The equipment for the tramway was supplied by the General Electric Company of the USA. Joseph Stillman Badger came out with the equipment to Brisbane in 1896 in install and set up the tramways. The Company asked him to stay on as General Manager, becoming managing director of the Company eventually.[5][6] The men wanted the right to wear the union badge. Two reportedly IWW organisers went to all the tramways in Australia to try to organise a simultaneous strike over the issue. Badger refused to negotiate with the union over the issue or the Queensland Council of Unions Queensland peak union body, then known as the Australian Labour Federation. After this rebuff a meeting of delegates from forty-three Brisbane based Trade Unions formed the Combined Unions Committee and appointed a General Strike Committee. The trade unionists of Brisbane went out on a general strike on 30 January 1912, not just for the right to wear a badge but for the basic right to join a union. The tramway men in Broken Hill were the only other ones outside of Queensland to go out on strike over the issue. The other systems tramway men had little sympathy with the cause at it had already been listed for hearing before the Arbitration Tribunal.

Within a few days the Strike Committee became an alternative government. No work could be done in Brisbane without a special permit from the Strike Committee. The committee organised 500 vigilance officers to keep order among strikers and set up its own Ambulance Brigade. Government departments and private employers needed the Strike Committee's permission to carry out any work. The Strike Committee issued strike coupons that were honoured by various firms. Red ribbons were generally worn as a mark of solidarity, not only by people but also on pet dogs and horses pulling carts. This spread even to school children where either blue or red ribbons were worn depending on your side. Playground brawls were common.[7] Daily processions and public rallies were held to keep strikers occupied.

On the second day of the strike over 25,000 workers marched from the Brisbane Trades Hall to Fortitude Valley and back with over 50,000 supporters watching from the sidelines. The procession was described as being led by Labor parliamentarians, with the procession being eight abreast and two miles (3 km) long, with a contingent of 600 women. The strike spread throughout Queensland with many regional centres organising processions through their towns. The strike committee regularly issued an official Strike Bulletin to counter the expected anti-union bias in mainstream newspapers.

William McCormack and the Amalgamated Workers' Association of North Queensland (AWA) initially lent their support to the strike. However, McCormack considered the pretext for the strike to be flimsy and AWA members soon returned to work.[8]

It was only when the strike spread to the railways that the Queensland government became concerned about the situation. At this juncture it banned processions, swore in special constables and issued bayonets to its police force. Commonwealth military officers and spare-time troops volunteered as special constables, and many of the specials wore their commonwealth uniforms into action.

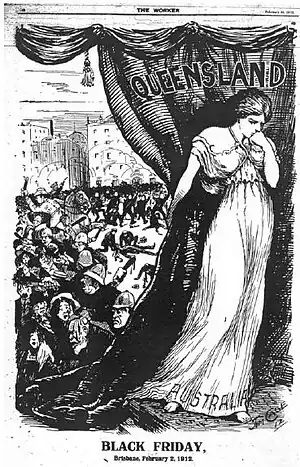

Black Friday

An application by the strike committee for a permit for a march on 2 February 1912 was refused by Police Commissioner William Geoffrey Cahill – the day came to be called Black Friday for the savagery of the police baton charges on crowds of unionists and supporters.

Despite the refusal of a permit, a crowd estimated at 15,000 turned up in Market Square. Police and Specials attacked crowds in Albert Street under the direction of Cahill, who shouted, "Give it to them, lads! Into them." Meanwhile, Emma Miller, a pioneer trade unionist and suffragist, led a group of women and girls to parliament house and, while returning along Queen Street, were batoned and arrested by a large contingent of foot and mounted police. Emma Miller, a frail woman in her 70s barely weighing 35 kilograms, stood her ground, pulled out her hat pin and stabbed the rump of the Police Commissioner's horse. The horse reared and threw off the Police Commissioner, giving him an injury resulting in a limp for the rest of his life. There is some debate that Miller's hatpin stabbed Cahill in the leg.[9][10]

The riding down and batoning of peaceful people, many of them being elderly and women and children on the footpath, was widely condemned, not only in union papers such as the Worker, but also in the more conservative papers such as Truth. It was initially called Baton Friday, but later came to be popularly known as Black Friday.

Conservative Queensland Premier Digby Denham, viewed the strike committee as an opposing alternate administration and said there were "not going to be two governments" and opposed all further permits for processions. It was generally viewed as more of an insurrection than a strike by the conservative media and the Government, which is what the IWW organisers had really wanted Australia wide following their success with the 1908 Sydney tramway strike. When he attempted to enlist support of the Federal Government in the use of the military, he was rebuffed by the Labor Prime Minister, Andrew Fisher, member for the Queensland seat of Gympie. Fisher had also received a request for military support from the Combined strike committee, but declined this offer preferring to send a monetary donation in support of the strike.

Aftermath

Justice H.B. Higgins in the Federal Arbitration Court ruled that the precipitating event was a lockout rather than a strike, and that the regulation refusing tramwaymen the right to wear their union badges on duty was both unauthorised and unreasonable. Higgins could not intervene in restoration of jobs.[11]

When the Employers Federation agreed on 6 March 1912 that there would be no victimisation of strikers the strike officially ended.[12]

The savagery of the baton charges by the Queensland Police Service and specials on Black Friday created a bitterness and hatred of the police which would last for several decades. The strike reinforced solidarity and collective identity of the Australian labour movement in Queensland. The Denham government immediately won an ensuing election on a "Law and Order" platform and passed the Industrial Peace Act of 1912 ushering in compulsory arbitration specifically to deter strikes in essential services.

Employees of the tramway company who had struck were sacked. The tramway company refused to ever re-hire these workers. When the tram system was acquired by the Queensland Government in 1922 the sacked workers were reinstated. Badges on uniforms – the cause of the strike – were forbidden even when the tram system (and later bus system) was under government and later Brisbane City Council control and were to remain forbidden until 1980.

In the aftermath of the strike three years later there was an electoral swing to Labor all over Queensland, and the second Queensland Labor Government was elected in 1915, led by T. J. Ryan.

In culture

The play, Faces in the street : a story of Brisbane during the general strike of 1912 : a play in two acts written by Errol O'Neill was performed for the first time in 1983 by La Boite Theatre.[13]

References

- ↑ company records of the Metropolitan Tramway and Investment Co and The Brisbane Tramway Company and related entities in the Queensland National Bank Archives (held by the NBA)

- ↑ Ford, Garry R. Brisbane, Qld. Royal Historical Society of Queensland, 1977

- ↑ Development of the horse tramways of Brisbane Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland volume 9 issue 5: pp. 115-137

- ↑ Ford, Garry R. Brisbane, Qld. Royal Historical Society of Queensland, 1974

- ↑ entry for Joseph Stillman Badger in the Australian Dictionary of Biography

- ↑ Joseph Stillman Badger : the man and his Tramways Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland volume 10 issue 2: pp. 54-66;

- ↑ Education dept school files when doing research for the Centenary of Education book

- ↑ Kennedy, K. H. (1986). "McCormack, William (1879–1947)". Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- ↑ Pam Young, The Hatpin – A Weapon: Women and the 1912 Brisbane General Strike, published in Hecate, (1988)

- ↑ Pam Young, Proud to be a Rebel – The Life and Times of Emma Miller, University of Queensland Press, 1991. ISBN 0-7022-2374-3

- ↑ D,J. Murphy The Tramway and General Strike, 1912 in The Big Strikes: Queensland 1889–1965, University of Queensland Press, 1983 ISBN 0-7022-1721-2

- ↑ "Australians general strike for right to unionize, Brisbane, Australia, 1912". The Commons. 30 September 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ↑ "Errol O'Neill Archives". Playlab Theatre. Retrieved 9 January 2020.