| 1917 Twin Cities streetcar strike | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of streetcar strikes in the United States | |||

| |||

| Date | October 6–9, 1917 (Initial strike, 3 days) November 25, 1917 (lockout) December 13, 1917 (General strike) | ||

| Location | Minneapolis–Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States | ||

| Caused by | Low wages and poor working conditions | ||

| Goals |

| ||

| Methods | |||

| Resulted in | Company fires several unionized employees, resists union demands, succeeds in breaking the strike | ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Number | |||

| |||

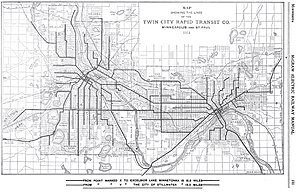

The 1917 Twin Cities streetcar strike was a labor strike involving streetcar workers for the Twin City Rapid Transit Company (TCRT) in the Minneapolis–Saint Paul metropolitan area of the U.S. state of Minnesota, popularly known as the Twin Cities. The initial strike lasted from October 6 to 9, 1917, though the broader labor dispute between the streetcar workers and the company lasted for several months afterwards and included a lockout, a sympathetic general strike, and months of litigation before ending in failure for the strikers.

The labor dispute began in August 1917, when streetcar workers began to openly discuss their grievances regarding their poor working conditions and low pay. In September, the workers met with Horace Lowry, the president of the company, to discuss possible wage increases and changes to working conditions, though Lowry resisted both. As a result, the workers organized with the International Amalgamated Association of Street and Electric Railway Employees, which established two local unions in the Twin Cities. Lowry responded by firing several union employees and offering remaining employees a ten percent wage increase, though they rejected the offer because it would not have included the rehiring of those employees. Fearing a possible labor strike, the Civic and Commerce Association, Minneapolis's employers' organization, mobilized the Civilian Auxiliary, an auxiliary group they had formed at the beginning of the United States's entry into World War I earlier that year.

On October 6, the streetcar workers went on strike, which went relatively peacefully in Minneapolis, but became violent in nearby Saint Paul, where a mob of about 3,000 people roamed the streets and committed acts of violence and property damage against both TCRT and non-TCRT owned property. The violence became so bad that Minnesota Governor Joseph A. A. Burnquist mobilized the state's home guard. On October 9, the Minnesota Commission of Public Safety (MCPS, a watchdog organization formed by the state government during the war) became involved, bringing an end to the strike as they mandated that the company institute improved working conditions and pay increases while they reviewed the terminations on a case-by-case basis. While the union claimed a partial victory with the strike, the company soon after began to plan ways to damage the union. They created a company union whose members often engaged in confrontations with amalgamated union employees, prompting the streetcar union to request the MCPS to intervene again. The MCPS organized a committee to address both sides' grievances and ultimately found in favor of the company, ruling that the union could not solicit or propagandize on company property, such as with wearing buttons advocating for the union. Taking advantage of the ruling, the company committed a lockout of about 800 union employees on November 25, further inflaming tensions. On December 2, a pro-labor rally at Saint Paul's Rice Park in support of the streetcar workers turned violent and resulted in a mob of about 2,500 damaging property in the city, and around the same time, labor leaders in the Twin Cities announced plans for a general strike. This general strike, which involved about 10,000 workers, was held on December 13 and was called off after less than four hours when it was announced that federal mediators would become involved in the streetcar labor dispute. The mediators found in favor of the union, but the company refused to obey their recommendations, which the mediators were powerless to enforce, and the union, which had previously agreed to a no-strike clause, was powerless to protest. After several months of litigation stretching into 1918, the labor dispute ended in failure for the union.

Following World War I, the Civilian Auxiliary and the MCPS would be disbanded. It would take until 1934 for employees of the TCRT to become unionized under the banner of the Amalgamated Transit Workers Union. The company would continue operations until 1970, when its assets were absorbed by Metro Transit. Discussing the strike in a 2001 book, historian Mary Lethert Wingerd said, "I think it’s one of the most important events in the history of Minnesota, and one of the least recognized". Wingerd states that the strike exposed the federal government's limited power in addressing local labor disputes and resulted in later changes at the national level to address this. Additionally, the strike, which was supported by the Nonpartisan League, resulted in closer collaboration between organized labor and agricultural interests, contributing to the formation of the Minnesota Farmer–Labor Party the following year.

Background

Twin City Rapid Transit Company

By the beginning of the 1900s, electric streetcars had mostly replaced horse-drawn streetcars and cable cars as the dominant form of public transit in many cities across the United States.[1] In the U.S. state of Minnesota, may cities had electric streetcar systems, including Duluth, East Grand Forks, and Winona.[1] The streetcar systems for the neighboring cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul (which form a metropolitan area commonly referred to as the "Twin Cities") had been electrified in 1891, and that same year, the systems merged to form the Twin City Rapid Transit Company (TCRT),[2] which held a monopoly on public transit in the cities.[3] As in other localities, the Minneapolis-based company was granted a franchise by the cities to lay tracks and operate on their public roads, but in exchange, the company had to provide certain public services at its own cost, such as maintaining the road surface and performing snow removal.[4][5] The company had a board of directors that included many noted area citizens and was led by its president, Thomas Lowry, a real estate developer who had been involved in the creation of many of the Twin Cities' neighborhoods, which were serviced by the streetcars.[3] He died in 1909, and by 1915, his son, Horace Lowry, had become the president of the company.[6] By the mid-1910s, the company was struggling financially as its operating expenses had grown over the past several years.[6] Additionally, while the company wanted to raise its fare, the prices were set by the local governments of Minneapolis and Saint Paul, and the local politicians did not want to raise the nickel-fare that had been in place since before the system had been electrified.[6]

Labor organizing amongst the streetcar workers

Conductors and motormen for the company during this time experienced poor working conditions, working up to 12-hour shifts with no paid time off.[7] As a result, starting in August 1917[8][9] and continuing into September, workers began to hold talks with labor union activists and pushed for a wage increase of $0.03 per hour.[10][5] In September, a committee of streetcar workers met with Lowry and company management to demand increased wages and improved working conditions, though Lowry denied these requests, citing inadequate revenue that could not cover the increased costs.[7] After this, many of the workers sought assistance from the Minneapolis Trades and Labor Assembly, the local trades council.[7] On September 23, 32 workers held a meeting to discuss unionizing.[11] Many unions during this time were taking advantage of the general nationwide labor shortage caused by the U.S. involvement in World War I by pushing for higher wages, better working conditions, and union recognition.[12] The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), a radical anticapitalist union that had regional headquarters in downtown Minneapolis,[12] was one such organization, and many employees who had pushed for the wage increases and better working conditions had ties to the group.[13]

By September 25, Lowry had discovered the identity of 20 of the 32 men who had participated in the union meeting on September 23 and immediately fired them.[11] This incensed many of the workers, and on October 1,[11] about 400 workers held a meeting to discuss the situation with the company and decided to fully unionize with the International Amalgamated Association of Street and Electric Railway Employees, a union for streetcar employees,[7] whose organizers established two local unions for the streetcar workers in Minneapolis and Saint Paul.[10] Around the same time, Lowry attempted to counter the growing labor movement in his company by offering a ten percent wage increase to remaining employees, though this offer was rejected because it would not have included the rehiring of the fired men.[8] At the same time, Lowry fired another 37 workers for union activities.[11] Alongside this one of the fired union workers was attacked by a foremen with another non-union employee holding him down, this was after he demanded the pay from his last week of work before being discharged.[14] With no progress in negotiating with Lowry, the streetcar workers began to prepare for a labor strike.[8] It would not be the first in the history of the Twin Cities streetcar system, as in 1889, workers for the Minneapolis Street Railway Company (a predecessor of the TCRT) went on strike over a wage decrease.[15]

Political developments in Minnesota

Several months prior to the start of the labor dispute between streetcar workers and management, the United States entered into World War I.[12][16] In the immediate aftermath, the government of Minnesota enacted a law to create the Minnesota Commission of Public Safety (MCPS), a watchdog group that was led by Minnesota Governor Joseph A. A. Burnquist and was granted broad powers to ensure the state's protection from foreign threats and oversee its war effort.[12][16] For the duration of the war, the MCPS targeted many groups that they deemed a possible threat, including socialists, German Americans, the Nonpartisan League, the IWW, and organized labor in general.[16] With the federalization of the Minnesota National Guard, the MCPS also created a state home guard, the Minnesota Home Guard, as a military organization for the state.[17] According to an article published by the Minnesota Historical Society, "The MCPS employed the Home Guard as a de facto police force to quell labor disputes".[17]

In the Twin Cities, Saint Paul was a closed shop city where almost all employers recognized union workers, while organized labor in Minneapolis was less strong, resulting in a more open shop city.[5] This was due in part to the actions of the Minneapolis Citizens' Alliance,[18][19] a local anti-union group that was closely associated with the city's employer's organization, the Minneapolis Civic and Commerce Association (CCA).[20][9] The CCA included several hundred businessmen from the area,[21] including its leader John F. McGee, who was also a member of the MCPS.[22] In April 1917, due to the outbreak of war, the CCA established the Civilian Auxiliary, an auxiliary group consisting of several hundred men, including many CCA members, who engaged in military training.[23] The group was led by Perry G. Harrison, a CCA member, and held exercises at the College of St. Thomas in Saint Paul.[24] According to historian William Millikan, the CCA had established the auxiliary out of fear that Governor Burnquist and the MCPS would be too hesitant to respond to a local issue, such as a labor strike.[23] However, per Millikan, "the fears and goals of the Public Safety Commission and the Civic and Commerce Association were identical".[25] Additionally, the CCA was concerned by the recently elected Minneapolis Mayor Thomas Van Lear, a member of the Socialist Party of America, who pledged that the Minneapolis Police Department would not be employed in strikebreaking under his mayorship.[26] With a possible streetcar strike imminent, officers in the Civilian Auxiliary met on September 6 at the Minneapolis Athletic Club to reorganize the group into four companies of 150 men each.[8] Additionally, the officers talked to Hennepin County Sheriff Otto S. Langum, a CCA member,[20] and on September 13, he deputized the Civilian Auxiliary.[8] On September 25, Sheriff Langum notified the auxiliary that they would be free to openly bear arms and make arrests.[8]

Course of the labor dispute

Early strike actions

The strike began at 1:00 a.m. CT on Monday, October 6.[8] Sheriff Langum was quickly notified and he ordered the Civilian Auxiliary to be mobilized, under the field leadership of Colonel Harrison and Major Henry Adams Bellows.[8] These two set up headquarters in a room in the Minneapolis Courthouse and began to assign companies to different areas of Minneapolis to defend streetcar employees and property, including their many carbarns.[8] Later in the day, a group of about 150 union supporters gathered around a carbarn at the intersection of Washington Avenue and 24th Street and attempted to convince working employees to join the strike.[27] However, the streetcars continued to operate on a normal schedule and, aside from some rock-throwing, the gathering was largely peaceful.[27] Later that day, a group of about 100 union sympathizers marched to the carbarn with weapons such as clubs and stones, though they were quickly dispersed by the auxiliary, who were equipped with Krag–Jørgensen and Springfield rifles.[27] One of the group leaders was arrested and charged with inciting a riot.[8] Over the next four days, the auxiliary remained on patrol and, aside from some sporadic incidents at this station,[7] the strike was relatively peaceful in Minneapolis.[27]

In Saint Paul, the strike was much more violent,[27] owing in large part to the strong influence that organized labor held over the city politics.[5] For several hours after the start of the strike, a mob of about 3,000 strikers moved through the streets and committed acts of property damage,[10][5] such as smashing windows and attacking operating streetcars.[27] The St. Paul Pioneer Press reported during the strike, "Wild rioting in which the police were unable to control mobs numbering in the thousands marked the end of the first day of the street car strike",[27] while Minnesota historian Mary Lethert Wingerd later stated, "the situation had escalated into a full-scale riot, like nothing St. Paul had ever seen".[5] As a result, by 11 p.m.,[5] the company decided to temporarily shut down operations in Saint Paul.[28] The Saint Paul Police Department, whose officers were unionized, was hesitant to suppress the riot.[29] In Minneapolis, Sheriff Langum posted guards at all of the bridges connecting the two cities to prevent the spread of violence from Saint Paul.[30] The violence was so great that Governor Burnquist ordered in federal soldiers from Fort Snelling to quell the rioting.[7] In total, about 500 troops from several units of the Minnesota Infantry were brought in to restore order.[30] In total, 11 men were arrested, while 20 were injured during the rioting.[5] According to Wingerd, the rioting, which had begun as a labor dispute between the workers and streetcar company, had quickly taken the form of a "community protest" that involved many Saint Paulites airing various grievances, including from several uniformed soldiers who participated,[5][31] and the local St. Paul Daily News described the event as having the atmosphere of "a state fair", noting the presence of vendors selling popcorn and peanuts.[5] On October 8, Lowry purchased a full-page advertisement in the Saint Paul Dispatch in an attempt to garner public sympathy against the strike, saying, "a small group of men, outside of our organization, have, for political and personal advantage, attempted to create discord between you and your management. ... Can we for a moment either as employees charged with a public duty, or as joint workers in a great industry entrust our interests to these men?"[10] The Pioneer Press also attempted to portray the event as the result of outside agitators, in particular IWW activists.[29]

By October 9, the MCPS decided to intervene and brought an end to the strike.[note 1] The commission ordered an immediate end to the strike and the reinstatement of fired workers while they began an investigation into the strike that included interviews with numerous union and company representatives.[30] The MCPS reviewed each termination on a case-by-case basis and by October 12, all but 13 of the 57 fired employees had their jobs back.[30] By that date, sporadic violence in Saint Paul had completely died down.[30] The union claimed a victory in this strike action, as the company agreed to an MCPS order to increase pay (resulting in a wage increase of ten percent)[13] and improve working conditions,[30] prompting the pro-labor Minneapolis Labor Review to report in an October 12 headline story, "Street Railway Strike Ends in Victory for Men".[10]

Interim

Following this initial strike action, Lowry and company management remained fearful of future union actions and decided to create a company union called the Trainmen's Cooperative and Protective Association.[30] This association, with Lowry as its head, was designed to counter the influence of the union and gave Lowry arbitration power over the members.[30] The association distributed buttons to its members, though this backfired as the union began to issue buttons of its own and increased recruitment efforts.[30] At one carbarn, about 160 employees left the association and joined with the union.[30] Tensions escalated between the two groups of workers, and daily instances of harassment, verbal abuse, and in some cases even physical violence were not uncommon.[30] On November 1, the union sent an appeal to the MCPS, which ordered all hostilities to cease as they assembled a committee to address both sides' grievances.[30][34] The committee initially consisted of President Samuel F. Kerfoot of Hamline University, Minneapolis lawyer Robert Jamison, and Saint Paul businessman Norman Fetter, though Jamison was later replaced by CCA member Waldron M. Jerome after it was revealed that Jamison owned stock in TCRT.[30] According to Millikan, this committee, which began holding hearings on November 7, was biased towards the union, and there were rumors that Fetter also owned stock in TCRT and that Hamline University had received a financial endowment from Horace Lowry.[35] While this committee continued to hold hearings, both the company and the union prepared for the next labor dispute.[36] Edward Karow, a captain in the Minneapolis Civilian Auxiliary, traveled to Saint Paul to organize an auxiliary force in that city, arming them with several hundred riot sticks and some rifles.[36] The union complained to Governor Burnquist that the auxiliary was in essence nothing more than a private army for employers and was illegally wearing United States Army clothing and brandishing rifles.[36] While the union wanted the auxiliary disbanded, the only change to come from this was that the group began to wear steel-gray uniforms instead of their previous khaki ones.[36]

On November 19, the committee released its recommendations, which included a ban on button-wearing by the streetcar workers and the prohibition of the union to solicit and propagandize on company property, which included the carbarns and the streetcars.[36] The MCPS adopted the committee's recommendations in full the following day, with the company given the ability to enforce the recommendations.[36] While both the company and the union had agreed to the button recommendation, the union had not agreed to the ban on soliciting and propagandizing, and after discussing the matter with the MCPS, the union agreed to hold a vote on November 26.[36] However, the company learned of the planned vote and on November 25 ordered that anyone seen wearing a button or soliciting would be fired immediately.[36] This resulted in a lockout of about 800 union members who had refused to comply with the company's demands, and the union viewed the move as an effort by the company to break the union.[36][32] These 800 men would later be fired by the company.[13] While the union contended that the recommendations did not carry the force of law and were thus unenforceable by the company, the MCPS, which supported the company, passed an order on November 27 that gave the recommendations the force of law, though the order also stipulated that the 800 men would be rehired.[36] However, the union still refused to comply.[36] That same day, the CCA reorganized the Minneapolis division of the American Protective League (APL), an organization nominally under the direction of the United States Department of Justice's Bureau of Investigation whose goal was to employ surveillance on certain groups during the war.[37] Approximately 400 members of the CCA joined the APL, which was headquartered in the local federal building.[37]

Pro-labor riot in Saint Paul

On December 2, tensions came to a head during a pro-union rally at Saint Paul's Rice Park that had been organized by labor groups in the Twin Cities.[38][10][32] After the rally, despite calls by labor leader speakers to engage in peaceful demonstrations,[32] a large group of people (later reported by the Pioneer Press as about 2,500)[5] took to Saint Paul's streets and began to damage TCRT company property and attack nonunion streetcar workers.[38] The actions caused the company to suspend afternoon operations in the city and resulted in about 50 nonunion streetcar workers getting injured.[38]

Ramsey County Sheriff John Wagener refused to offer protection to the streetcar company and the Saint Paul Police Department was unable to restore order, prompting the deployment of the Minnesota Home Guard at 6:00 p.m.[38] Within two hours, the Home Guard had dispersed crowds from Downtown Saint Paul and had erected barricades in certain areas of the city.[38]

Over the next several days, additional troops arrived from across the state, from cities such as Austin, Crookston, Duluth, Morris, and Red Wing.[10] Governor Burnquist later removed Sheriff Wagener from his post due to his inaction, and though labor activists gathered 20,000 signatures calling for his reinstatement, this did not occur.[38] In Minneapolis, Sheriff Langum mobilized the Civilian Auxiliary shortly after rioting broke out in Saint Paul.[38] These men patrolled the streets in weather that dropped to as low as -25 degrees Fahrenheit and engaged in some sporadic scuffles with union members, but were able to prevent the widespread rioting that Saint Paul experienced.[37] During this conflict, the Northwestern National Bank donated 66 .30 caliber rifles with bayonets to the auxiliary.[37] Local media would later call this act of violence "The War of St. Paul".[13] In the aftermath, two speakers at the Rice Park rally, including James Manahan of the Nonpartisan League, who had pledged that group's support for the strikers, were arrested for inciting a riot, though these charges were later dismissed by a judge in Ramsey County.[5]

One labor newspaper's account of the secondary riot in Minneapolis was as follows.[39] The paper claims that the actions and presence of the Civilian Auxiliary, armed with pick handles as rudimentary clubs and pistols, provoked it. That they prodded workers with the handles and the prevented people from crossing street corners, leading fights to break out. It then concludes that at the end of the night a couple street car windows were broken and no one was injured except those beaten by the Civilian Auxiliary.[39] Another labor newspaper, The Minnesota Union Advocate, claims the streetcars power was shutdown right before an outside meeting ended.[40]

Plans for a general strike

While the violence had been quelled in the Twin Cities, a national gathering of union members scheduled for December 5 prompted fears of a general strike in the metropolitan area.[37] As a result, on December 4, United States Secretary of War Newton D. Baker, acting United States Secretary of Labor Louis F. Post, American Federation of Labor (AFL) president Samuel Gompers, and MCPS representative C. W. Ames met in Washington, D.C. to discuss the situation in the Twin Cities.[32] The group decided that the best course of action to prevent a full-scale general strike was to suspend the MCPS and reopen the case between the streetcar company and the union.[32] Secretary Baker notified Governor Burnquist that the federal government was willing to intervene to prevent more disturbances,[37] as they believed that a continued labor dispute in the cities could hurt the country's war effort.[32] McGee and the CCA were afraid that federal government intervention would hurt the organization's position of power in the Twin Cities and McGee notified both Secretary Baker and United States Secretary of the Treasury William Gibbs McAdoo that their intervention was unwarranted.[37] Governor Burnquist also resisted intervention and Secretary Baker opted to put these plans on hold for the time being.[37]

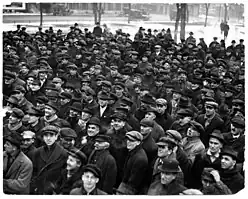

On the morning of Wednesday, December 5, about 15,000 unionists met at the Saint Paul Auditorium and heard speeches from notable labor activists, including Mayor Van Lear.[37] The unionists pledged their support to the streetcar union members and demanded the firing of both McGee and Charles W. Ames from the MCPS.[37] Additionally, they voted to wait until December 11 for federal intervention, vowing to gather again and vote on a general strike if intervention had not occurred by that time.[37] In a bid to show he was not antilabor, Governor Burnquist fired Ames, though kept McGee on the commission.[37] Several days later, on December 7, APL members learned through espionage that some machinist union members were planning a possible statewide general strike.[41] A general strike in the Twin Cities was officially declared to begin at 10:00 a.m. on December 13.[42][43] The union stated that they expected 30,000 people to go on strike, prompting fears that martial law would be declared.[42][44] Governor Burnquist ordered that all liquor stores be closed and instructed the sheriffs of both Hennepin and Ramsey counties to maintain order.[42] By noon, over 10,000 people had walked out of their jobs.[42][43] By that time, Secretary Baker, acting under the authority of United States President Woodrow Wilson, telegraphed William Bauchop Wilson of the President's Mediation Commission to investigate the developments in the Twin Cities, citing a "federal interest" in the matter.[42] Having achieved their goal of federal intervention, at 1:30 p.m., E. G. Hall, the president of the Minnesota chapter of the AFL, called off the strike.[42] In total, this general strike had lasted less than four hours,[32] with no reports of violence.[42] Governor Burnquist, while agreeing to meet with federal mediators, voiced stern opposition to the federal government's decision, calling it an overreach of their power.[42]

Federal mediation and the end of the dispute

The mediators held their inquiries at the Radisson Hotel in Minneapolis and heard testimony from representatives of many of the involved organizations, including the streetcar company, the unions, the CCA, the MCPS, and other politicians.[42] Additionally, before departing to Washington, D.C. to complete their investigation, the mediators had the unions sign an agreement not to strike.[42] According to Millikan, the decision by the unions to agree to not strike severely damaged the union members chances at winning this labor conflict, as, according to Millikan, "The unions refused to believe the obvious: Lowry and the [MCPS] fully intended to ignore any federal intervention".[42] While the mediators continued their investigations into January, the TCRT began to recruit nonunion workers from rural areas outside of the Twin Cities, while the CCA established an employment bureau to help find more workers.[42]

On February 14, 1918, the mediators released their recommendations, which stated that the streetcar company should rehire all union workers at prestrike wages and should not discriminate based on union membership.[45][46] Secretary Baker requested the MCPS to urge the company to comply with the recommendations, but Lowry responded that compliance "would be imposing a gross injustice" on nonunion members.[45] With the federal mediators powerless to enforce their recommendations and the MCPS unwilling to force the company to comply, the company remained steadfast in their refusal to rehire union members.[45] J. H. Walker, a member of the mediation commission, wrote that, "The company has positively refused to agree to the findings of the commission. ... They have thus put themselves squarely on record in opposition to the war policies of our government at this time".[45] Despite a campaign by labor activists in the state, the MCPS remained steadfast in opposition to forcing compliance, and on April 16, they issued an order to establish an industrial status quo, hurting the development of union activities in the state.[45] In accordance with the order, on June 12,[32] the Minnesota Board of Arbitration attempted to mediate between the company and the union, but the company refused to enter into any form of discussions with the union.[45] Despite this, the Board of Arbitration agreed with the findings of the presidential mediators, and the union then requested that the dispute be handled by the newly created National War Labor Board (NWLB).[45][32] However, on April 10, 1919, the NWLB dismissed the case, thus finally ending the streetcar labor dispute in the Twin Cities.[45]

Aftermath

In a 2001 book that discusses the strike, Minnesota historian Mary Lethert Wingerd stated, "I think it’s one of the most important events in the history of Minnesota, and one of the least recognized".[5] According to Wingerd, the strike had an impact on national politics, as it demonstrated the limited power the federal government held in dealing with labor issues.[47] As a result, the strike led to "a restructuring of federal powers" that foreshadowed later developments such as the New Deal several years later.[47] In Minnesota, the strike solidified opposition to the MCPS on the part of both labor and agricultural interests and led to a strengthening of the Farmer–Labor movement.[48] Wingerd cites the strike as the first time that the Nonpartisan League, which had supported the strike from the beginning,[9] and organized labor worked together towards their common interests, leading to the creation of the Minnesota Farmer–Labor Party, which ran candidates in the 1918 United States elections.[5] The Farmer–Labor Party would be one of the most successful third parties in U.S. history before merging with the Minnesota Democratic Party in 1944 to form the Minnesota Democratic–Farmer–Labor Party.[5] The CCA and its Civilian Auxiliary and the MCPS and its Home Guard continued to exert strong influence over state and local politics for the next several months, effectively silencing the IWW, Nonpartisan League, and vocal labor unions for the duration of WWI.[45] However, following the end of the war, the Home Guard and the Civilian Auxiliary were both disbanded as the Minnesota National Guard was defederalized.[17][49] The MCPS was also shuttered, being officially dissolved in 1920.[12]

The strike severely damaged the image of the TCRT in the eyes of many Twin Cities residents, especially its working class.[13] In 1920, the company succeeded in instating fare increases and the following year, legislation passed that benefitted the company in further raising fares.[13] However, according to historians John W. Diers and Aaron Isaacs, "The company won "The War of St. Paul" and its fare increases, but its obstinacy did nothing to improve its fortunes, as more and more streetcar riders became automobile owners".[50] Indeed, the company reached its peak in the 1920s in terms of revenue and ridership before entering into a decline brought on by the increased usage of the automobile.[51] The company would last until 1970,[2] when its assets were transferred to its public successor, Metro Transit.[10] Organized labor activities among public transit workers in the cities would continue for the next several decades, and in 1934, the workers succeeded in establishing union recognition under the Amalgamated Transit Workers Union, the new name of the International Amalgamated Association of Street and Electric Railway Employees.[10] In 2011, a novel by noted Twin Cities author and journalist Larry Millett was published that took place during the streetcar strike.[10]

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 Diers & Isaacs 2007, p. 3.

- 1 2 Diers & Isaacs 2007, p. 4.

- 1 2 Diers & Isaacs 2007, p. 5.

- ↑ Diers & Isaacs 2007, pp. 5–6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Woltman 2017.

- 1 2 3 Diers & Isaacs 2007, p. 99.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Diers & Isaacs 2007, p. 100.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Millikan 1986, p. 10.

- 1 2 3 Chrislock 1991, p. 187.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Nathanson 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Millikan 2001, p. 125.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Reicher 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Diers & Isaacs 2007, p. 101.

- ↑ "Car Men United For Freedom and U. S. Conditions". Minneapolis Labor Review. September 28, 1917. p. 1.

- ↑ Millikan 2001, pp. 18–20.

- 1 2 3 Millikan 2001, p. 102.

- 1 2 3 DeCarlo 2017.

- ↑ PBS 2016.

- ↑ Jorgenson 2009.

- 1 2 Millikan 1986, p. 4.

- ↑ Millikan 2001, p. 50.

- ↑ Millikan 1986, pp. 4, 6.

- 1 2 Millikan 2001, p. 124.

- ↑ Millikan 2001, pp. 124, 272.

- ↑ Millikan 1986, p. 6.

- ↑ Millikan 1986, pp. 4–5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Millikan 1986, p. 11.

- ↑ Millikan 1986, pp. 11–12.

- 1 2 Wingerd 2001, p. 185.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Millikan 1986, p. 12.

- ↑ Wingerd 2001, p. 184.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Cameron 2016.

- ↑ Millikan 2001, pp. 127–128.

- ↑ Millikan 2001, p. 128.

- ↑ Millikan 1986, pp. 12–13.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Millikan 1986, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Millikan 1986, p. 15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Millikan 1986, p. 14.

- 1 2 "Trouble Mon. Night Blamed on Deputies" (PDF). Minneapolis Labor Review. December 7, 1917. p. 1.

- ↑ "Organized Labor Took No Part in Street Car Riot" (PDF). THE MINNESOTA UNION ADVOCATE. December 28, 1917.

- ↑ Millikan 1986, pp. 15–16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Millikan 1986, p. 16.

- 1 2 Chrislock 1991, p. 198.

- ↑ Millikan 2001, p. 133.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Millikan 1986, p. 17.

- ↑ Millikan 2001, p. 134.

- 1 2 Wingerd 2001, p. 211.

- ↑ Chrislock 1991, p. 182.

- ↑ Millikan 2001, p. 197.

- ↑ Diers & Isaacs 2007, p. 102.

- ↑ Diers & Isaacs 2007, pp. 4–7.

Sources

- Cameron, Linda A. (April 20, 2016) [February 29, 2016]. "Twin Cities Streetcar Strike, 1917". MNopedia. Minnesota Historical Society. Archived from the original on December 1, 2022. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- Chrislock, Carl H. (1991). Watchdog of Loyalty: The Minnesota Commission of Public Safety During World War I. Saint Paul, Minnesota: Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-87351-264-0.

- DeCarlo, Peter J. (November 8, 2017) [January 20, 2015]. "Minnesota Home Guard". MNopedia. Minnesota Historical Society. Archived from the original on December 7, 2022. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- Diers, John W.; Isaacs, Aaron (2007). Twin Cities by Trolley: The Streetcar Era in Minneapolis and St. Paul. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-1-4529-1295-0.

- Dobbs, Farrell (2004) [1972]. Teamster Rebellion (2nd ed.). New York City: Pathfinder Press. LCCN 2004101521.

- Jorgenson, Ron (August 26, 2009). "75th anniversary of the Minneapolis truck drivers' strike–Part one". World Socialist Web Site. International Committee of the Fourth International. Archived from the original on December 1, 2021. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- Millikan, William (Spring 1986). "Defenders of Business: The Minneapolis Civic and Commerce Association versus Labor during W.W. I". Minnesota History. Saint Paul, Minnesota: Minnesota Historical Society Press. 50 (1): 2–17. ISSN 0026-5497. JSTOR 20178970.

- Millikan, William (2001). A Union Against Unions: The Minneapolis Citizens Alliance and Its Fight Against Organized Labor, 1903–1947. Saint Paul, Minnesota: Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-87351-499-6.

- Nathanson, Iric (September 2, 2011). "'The Magic Bullet' and the 1917 streetcar strike". MinnPost. Archived from the original on July 21, 2020. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- "Prairie Pulse 1330: Todd Sando; Twin Cities Streetcar Strike". PBS. June 3, 2016. Archived from the original on March 1, 2023. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- Reicher, Matt (November 25, 2019) [June 23, 2014]. "Minnesota Commission of Public Safety". MNopedia. Minnesota Historical Society. Archived from the original on January 22, 2023. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- Wingerd, Mary Lethert (2001). Claiming the City: Politics, Faith, and the Power of Place in St. Paul. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8885-6.

- Woltman, Nick (December 5, 2017) [December 2, 2017]. "How the 1917 streetcar riots shook St. Paul and reshaped Minnesota politics". St. Paul Pioneer Press. Archived from the original on December 6, 2022. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

Further reading

- Cameron, Linda A. (February 17, 2017) [February 22, 2016]. "Twin City Rapid Transit Company and Electric Streetcars". MNopedia. Minnesota Historical Society. Archived from the original on December 10, 2022. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- "Street Railway Company strike". Minnesota Historical Society. Archived from the original on March 1, 2023. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- "Minnesota Legacy Short | Street Car Strike of 1917". PBS. Archived from the original on March 1, 2023. Retrieved March 1, 2023.