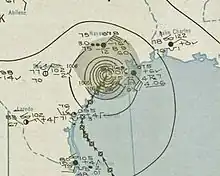

Surface weather analysis of the storm on August 28 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | August 24, 1945 |

| Dissipated | August 29, 1945 |

| Category 3 hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 115 mph (185 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 963 mbar (hPa); 28.44 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 3 |

| Damage | $20.1 million (1945 USD) |

| Areas affected | Texas |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1945 Atlantic hurricane season | |

The 1945 Texas hurricane was a slow-moving tropical cyclone which paralleled the Texas Gulf Coast, causing extensive damage in late-August 1945. The fifth tropical storm and second hurricane of the annual hurricane season, the storm formed out of an area of disturbed weather which had been situated over the Bay of Campeche on August 24. In favorable conditions, the system quickly intensified as it steadily moved northward, attaining hurricane intensity later that day. As it approached the coast, however, the hurricane quickly slowed in forward motion, allowing it time to intensify off the Texas coast. After reaching major hurricane status,[nb 1] the storm reached peak intensity on August 26 as a minimal Category 3 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 115 miles per hour (185 km/h). Later that day, the cyclone executed a slight curve toward the Texas coast, and early the next day made landfall near Seadrift at peak intensity. Once inland, it quickly weakened, and degenerated into a remnant low on August 29 over Central Texas. The storm was the first major hurricane to form in the Gulf of Mexico since 1941.

The hurricane's slow movement and strong intensity was a catalyst for extensive and damaging impacts in Texas. Prior to making landfall, thousands of people were ordered to evacuate from cities along coastal regions. Upon making landfall, the storm brought strong winds, which caused widespread power outages and infrastructural damage. A peak gust of 135 mph (217 km/h) measured in Collegeport, Texas. Northeast of Houston, Texas, a tornado killed a person after traveling for 22 mi (35 km). At the coast, the hurricane produced a strong storm surge which swept and damaged port cities. Port Lavaca, Texas was inundated by a 15 ft (4.6 m) storm surge, which at the time was the third highest ever recorded in the state. Damage in the port alone was estimated to be as high as $1 million.[nb 2] The strong wave action killed two people when it capsized a fishing vessel. Further inland, the storm produced torrential rainfall, which was also aided by the hurricane's slow movement. Rainfall peaked at 19.6 in (500 mm) in Hockley, Texas. The heavy rains caused extensive crop damage, particularly to cotton and rice crops. Damage to cotton in the Corpus Christi, Texas area alone was estimated at $1.5 million. Overall, the hurricane caused $20.1 million in damage, mostly to crops, and three deaths.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

Towards the end of August 1945, an area of squally weather persisted in the Bay of Campeche, near the Gulf Coast of Mexico. After a prolonged period of marginal development, the cluster of thunderstorms began to quickly organize beginning on August 24.[2] According to HURDAT – the official database listing positions and intensities of Atlantic tropical cyclones dating back to 1851 – the disturbance became sufficiently organized to be classified as a tropical storm by 0000 UTC on August 24. At the time, the storm already maintained maximum sustained winds of 45 mph (72 km/h). Initially, the tropical storm moved generally northward at approximately 18 mph (29 km/h), but gradually slowed as it neared the United States Gulf Coast. Quickly developing past tropical cyclogenesis, the system reached the equivalent of a modern-day Category 1 hurricane at 0600 UTC on August 25.[3] Its forward motion continued to slow until it moved nearly stationary at roughly 5 mph (8.0 km/h), which allowed the system to remain a tropical cyclone for an extended period of time, despite its proximity to the coast.[2] The hurricane's intensity continued to quickly increase, and by 1200 UTC on August 26, the storm had attained major hurricane status, the equivalent of a modern-day Category 3 hurricane.[3]

The hurricane executed a slight curve to the northeast later that day, causing it to move inland over the Texas coast.[3] Initially, the major hurricane was analyzed to have made landfall early on August 27 over Port Aransas with winds of 140 mph (225 km/h), equivalent to a modern-day Category 4 hurricane.[2][3] However, a reanalysis was conducted on the system, and concluded that it had only attained Category 3 intensity before making landfall at 1200 UTC that day. The reanalysis moved the landfall point closer to Seadrift as well.[3] At the time, the storm had maximum sustained winds confined within an area about 10 miles (16 km) from the hurricane's center. The reanalysis also concluded that the storm contained a minimum central pressure of 963 millibars (28.44 inHg) at landfall.[4] Once inland, the hurricane slowly weakened, but maintained hurricane intensity until 1200 UTC on August 28. After further weakening to a tropical depression by 0000 UTC the next day, the disturbance dissipated over the Texas interior at 1800 UTC on August 29.[2][3]

Preparations and impact

Upon classification as a hurricane by the former United States Weather Bureau (USWB) on August 25, a hurricane warning was issued for coastal areas between Corpus Christi and Brownsville, Texas, and between Galveston, Texas and Lake Charles, Louisiana. At the time, the storm was forecast to make landfall between Port O'Connor and Freeport, Texas.[5] However, all small craft offshore from the mouth of the Rio Grande and Burrwood, Louisiana were warned to remain in port or return to the coast. All other shipping in the western Gulf of Mexico were advised to exercise extreme caution.[6] Despite having just formed, forecasters already suggested that it would be potentially the most destructive storm of the hurricane season thus far.[7] As a result of the storm's intensity and repeated warnings, thousands evacuated potentially affected coastal regions.[8] In Freeport, Texas, 20,000 people evacuated.[9] Mustang Island was fully evacuated prior to the storm impacting land.[10] Throughout the hurricane's early developmental stages, reconnaissance flights were periodically made into the storm to gather data.[11]

Though situated on the opposite side of the Gulf of Mexico as Florida, tropical moisture extending from the hurricane caused torrential rainfall in the state. In St. Petersburg, the heavy rains set a 30-year record and flooded low-lying areas. Inundated streets blocked traffic and delayed transit bus routes. In Booker and Salt Creeks, the floodwaters backed up sewage systems. Though there were no deaths as a result of the floods, two people were rescued by police after their house was surrounded by water. Telecommunications in the Tampa Bay Area were delayed for up to two hours due to damage sustained to communication lines as a result of the rains. Despite its nearby proximity, effects in Tampa, Florida were much less severe, with only small showers and gusts never exceeding 25 mph (40 km/h).[11]

Upon making landfall on the Texas coast late on August 27, the hurricane caused a wide swath of destruction, and was considered one of the worst hurricanes to impact the state in at least 25 years. A 400 mi (645 km) wide swath of land experienced moderate to severe impacts during the storm.[12] Strong winds were reported in various locations, with a peak gust of 135 mph (217 km/h) measured in Collegeport, Texas.[8] At a weather station in Naval Air Station Corpus Christi, a wind gust of 101 mph (163 km/h) was measured. Across Corpus Christi, the strong winds knocked down communication and power lines, causing widespread power outages. Thus, all local radio stations were off air for a period of time. However, power was quickly restored within an hour after cutoff. Winds within the city peaked at 75 mph (121 km/h).[13] Damage in the city was estimated to be below $100,000.[14] Further south in Port Isabel, Texas, winds peaked at 76 mph (122 km/h). However, in nearby Brownsville, Texas, damage associated with the hurricane.[13] In El Campo, Texas, strong winds blew the roof off of a local hospital. Thus, 30 patients were evacuated to hospitals in Wharton, Texas.[12] Power in Wharton was temporarily knocked out for a short time.[15] As the storm progressed further inland, additional damage was reported. In Bay City, Texas, gusts uprooted trees and scattered debris over the city streets. Heavy rains there inundated roads under as much as 2 ft (0.61 m) of water. As a result, only one highway remained open. In Rockport, Texas, additional homes were unroofed, with damages estimated at $500,000.[9] Offshore, the hurricane produced strong waves which caused coastal impacts. In Port Aransas, Texas, waves inundated roads to a depth of 4 ft (1.2 m).[13] The strong waves later separated the port from the mainland, and destroyed or damage all buildings and structures there, causing an estimated $750,000 in damage there.[16][17] Power in Port Aransas was disrupted during the night of August 27. At Aransas Pass, surf was as high as automotive running boards.[13] At Port Lavaca, Texas, the tide rose up to 15 ft (4.6 m) above normal, inundating the coastal city and forcing the coastline to retreat 50 ft (15 m) from its initial position.[8] At the time, the measured storm surge was only the third highest recorded in Texas history, behind peak measurements taken during the 1900 Galveston hurricane and 1919 Florida Keys hurricane.[18] Damage estimates for Port Lavaca ranged from $750,000–$1 million.[16] Offshore of Port Isabel, the strong waves capsized a fishing vessel, killing all two of its crew members.[13]

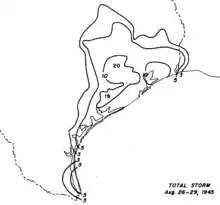

The hurricane's slow movement parallel to the Texas coast resulted in torrential rainfall, peaking at 19.6 in (500 mm) near Hockley over a period of a little over three days.[19] The excessive precipitation helped increase monthly rainfall amounts in the region to three times above average.[20] Cotton and rice crops were badly damaged during the storm.[12] The American Crop Growers Association estimated that up to 20% of the rice crop was lost during the stom.[16] Damage to unpicked cotton in the Corpus Christi area alone totaled to $1,500,000.[21] In Houston, the heavy rains halted traffic and increased flood risk to property near the city's bayous. Precipitation in the city peaked at 15.65 in (398 mm) in a 24-hour period.[12] However, the Barker Dam prevented a large scale flooding event in the city.[22] A gust of 55 mph (89 km/h) collapsed a suburban residence, killing the occupant inside.[12] Approximately 8 mi (13 km) north-northeast of Houston, an F3 tornado formed and traversed for 22 mi (35 km) across the northern suburbs of the city,[2] killing a person and causing 15 injuries.[23] The tornado also had a path width of 75 yd (69 m), and damage to property was estimated at $35,000.[2][24] Heavy rainfall from the storm was reported as far west as San Antonio, Texas.[25] Overall, the hurricane caused $20.1 million in damages, with $14 million attributable to agricultural losses, $5.883 million to infrastructural damage, and $250,000 to cattle and poultry losses. Despite the large swath of devastation, only three people were killed due to the extensive precautionary measures taken before the storm.[2]

After the hurricane passed, the American Red Cross and other relief agencies began to survey damage and assist in repair and rehabilitation activities. Red Cross personnel in the central coastal area assisted 15,000 refugees with food and care necessities. Robert Edison, then-director of the Midwest sector of the agency, requested 5,000,000 ft (1,500,000 m) of lumber and 52 tons (47 tonnes) of steel.[21] The Salvation Army, stationed in Houston, issued an appeal for clothing materials. State health department and agency crews were dispatched to check water and other sanitation facilities.[17]

See also

Notes

- ↑ A major hurricane is a storm that ranks as Category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane scale.[1]

- ↑ All damage totals are in 1945 United States dollars unless otherwise noted.

References

- ↑ Landsea, Chris (June 2, 2011). "A: Basic Definitions". In Dorst, Neal (ed.). Hurricane Research Division: Frequently Asked Questions. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. A3) What is a super-typhoon? What is a major hurricane ? What is an intense hurricane ?. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Sumner, H.C.; United States Weather Bureau (March 5, 1946). "North Atlantic Hurricanes and Tropical Distruabnces of 1945" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. Washington, D.C.: American Meteorological Society. 74 (1): 1–5. Bibcode:1946MWRv...74....1.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1946)074<0001:MACDFJ>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ Hagen, Andrew B.; Strahan-Sakoskie, Donna; Luckett, Christopher (1 July 2012). "A Reanalysis of the 1944–53 Atlantic Hurricane Seasons—The First Decade of Aircraft Reconnaissance" (PDF). Journal of Climate. Miami, Florida: American Meteorological Society. 25 (13): 4441–4460. Bibcode:2012JCli...25.4441H. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00419.1. S2CID 129284686. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- ↑ "Tropic Hurricane Near Texas Coast". The Evening Independent. New Orleans, Louisiana. Associated Press. August 25, 1945. p. 1. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- ↑ "Hurricane Down South". The Windsor Daily Star. New Orleans, Louisiana. August 25, 1945. p. 4. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- ↑ "Hurricane Headed For U.S. Gulf Coast". The Lewiston Daily Sun. New Orleans, Louisiana. Associated Press. August 24, 1945. p. 1. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Roth, David M; Weather Prediction Center. Texas Hurricane History (PDF). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- 1 2 "Texas Town Being Torn Asunder by Hurricane". Schenectady Gazette. Houston, Texas. Associated Press. August 27, 1945. p. 1. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- ↑ "110-M.P.H. Tropic Hurricane Moves Inland Over Texas". Toronto Daily Star. Corpus Christi, Texas. Associated Press. August 27, 1945. p. 2. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- 1 2 "Storm In Gulf Causes Heavy Rains In City". St. Petersburg Times. August 25, 1945. p. Section 2, Page 11. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Rains Flood Houston But Hurricane Abates". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Houston, Texas. Associated Press. August 28, 1945. p. 1. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Hurricane Hits 200-Mile Coastal Area In Texas; Center At Corpus Christi". St. Petersburg Times. Corpus Christi, Texas. Associated Press. August 27, 1945. p. 1. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- ↑ "Violent Hurricane Moves Slowly Along Coast of Texas". The Free-Lance Star. Corpus Christi, Texas. Associated Press. August 27, 1945. p. 1. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- ↑ Barnard, William C. (August 28, 1945). "Hurricane's Strength Diminishes". The Evening Independent. Houston, Texas. Associated Press. p. 1. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Storm Isolates Eastern Texas". St. Petersburg Times. Houston, Texas. Associated Press. August 29, 1945. pp. 1–2. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- 1 2 "Hurricane Damage May Hit $15,000,000 Mark". The Evening Independent. Houston, Texas. Associated Press. August 29, 1945. p. 13. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- ↑ "Some Maximum Storm Surge Records For Texas Storms". Houston, Texas: Weather Research Center. January 6, 2007. Archived from the original on August 19, 2016. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- ↑ Schoner, R.W.; Molansky, S. "Rainfall Associated With Hurricanes (And Other Tropical Disturbances)" (PDF). United States Weather Bureau's National Hurricane Research Project. p. 28. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- ↑ Jordan, C. R. (August 1, 1945). "River Stages And Floods For August 1945" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. Miami, Florida: American Meteorological Society. 73 (8): 140. Bibcode:1945MWRv...73..140J. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1945)073<0140:RSAFFA>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- 1 2 Alexander, John D. (August 29, 1945). "Hurricane Damage Runs Into Millions". San Jose News. Houston, Texas. United Press. p. 18. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- ↑ "8 Known Dead In Texas Gulf Hurricane". 8 Known Dead in Texas Gulf Hurricane. Houston, Texas. United Press. August 29, 1945. p. 5. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- ↑ Baldwin, J.L. (December 1, 1945). "Preliminary Report Of Tornadoes In The United States During 1945" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. Washington, D.C.: American Meteorological Society. 73 (12): 207–210. Bibcode:1945MWRv...73..207B. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1945)073<0210:PROTIT>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- ↑ Souder, Mary O. (August 1, 1945). "Severe Local Storms For August 1945" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 73 (8): 145–146. Bibcode:1945MWRv...73..145.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1945)073<0145:SLSFA>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- ↑ Keys, William E. (August 26, 1945). "Hurricane Hits Coast Of Texas; Wind At 110 MPH". The Lewiston Daily Sun. Corpus Christi, Texas. Associated Press. pp. 1, 8. Retrieved March 28, 2013.