| 1st Parliament of Great Britain | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

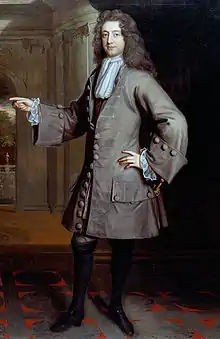

John Smith, Speaker | |||||

| Overview | |||||

| Term | 23 October 1707 – 14 April 1708 | ||||

| House of Commons | |||||

| Members | 558 MPs | ||||

| Speaker of the House of Commons | John Smith | ||||

| House of Lords | |||||

| Lord Keeper of the Great Seal | William Cowper | ||||

| Sessions | |||||

| |||||

The first Parliament of the Kingdom of Great Britain was established in 1707 after the merger of the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland. It was in fact the 4th and last session of the 2nd Parliament of Queen Anne suitably renamed: no fresh elections were held in England or in Wales, and the existing members of the House of Commons of England sat as members of the new House of Commons of Great Britain. In Scotland, prior to the union coming into effect, the Scottish Parliament appointed sixteen peers (see representative peers) and 45 Members of Parliaments to join their English counterparts at Westminster.

Legal background to the convening of the 1st Parliament

Under the Treaty of Union of the Two Kingdoms of England and Scotland it was provided:

III. THAT the United Kingdom of Great Britain be Represented by one and the same Parliament to be stiled the Parliament of Great Britain.

...

XXII. THAT ... A Writ do issue ... Directed to the Privy Council of Scotland, Commanding them to Cause ... forty five Members to be elected to sit in the House of Commons of the Parliament of Great Britain ... in such manner as by a subsequent Act of the present session of the Parliament of Scotland shall be settled ... And that if her Majesty, on or before the first day of May next, on which day the Union is to take place shall Declare ... That it is expedient that the ... Commons of the present Parliament of England, shall be members ... of the first Parliament of Great Britain, for and on the part of England ... and the members of the House of Commons of the said Parliament of England and the forty five Members for Scotland ... shall be ... the first Parliament of Great Britain ...

Queen Anne did declare it to be expedient that the existing House of Commons of England sit in the first Parliament of Great Britain.

The Parliament of Scotland duly passed an Act settling the manner of electing the sixteen peers and forty five commoners to represent Scotland in the Parliament of Great Britain. A special provision for the 1st Parliament of Great Britain was "that the Sixteen Peers and Forty five Commissioners for Shires and Burghs shall be chosen by the Peers, Barrons and Burghs respectively in this present session of Parliament and out of the members thereof in the same manner that Committees of Parliament are usually now chosen shall be the members of the respective Houses of the said first Parliament of Great Britain for and on the part of Scotland ..."

The Kingdom of Great Britain came into existence on 1 May 1707.

Continuity with English parliament

The last English parliament (Queen Anne's second parliament) officially began on 14 June 1705 and sat for three sessions. The first session met from 25 October 1705 to 19 March 1706, the second from 3 December 1706 to 8 April 1707 and the third from 14 April 1707 to 24 April 1707.

According to a clause of the Act of Union, Anne had until 1 May 1707 to convert the current sitting members of the English parliament into the English members of a British parliament, otherwise she would have to call for fresh elections.

In her closing speech of 24 April 1707, Anne informed the English parliament of her intention to exercise the treaty clause before 1 May and have current members of the English parliament sit in the first British parliament.[1] After the speech, at Anne's command, parliament was prorogued until 30 April. On 29 April, as promised in her speech, Anne invoked the clause of the Act of Union reviving the parliament by proclamation. In another proclamation on 5 June, Anne listed the Scottish members (16 peers and 45 commissioners) by name and, without issuing new writs of summons, the Queen scheduled the first parliament of Great Britain to "meet and be holden" on 23 October 1707.

It was not immediately clear, for the purposes of the 1694 Triennial Act, whether the First Parliament of Great Britain would count as a "new" parliament or as a continuation of the current English parliament that had already sat for two years. Some (e.g. Harley) argued that it was a continuation, as it was not summoned by fresh writs, and thus expected its term would expire 14 June 1708, and it would have to be dissolved and new elections called before the deadline. But others (e.g. Marlborough) argued that because Anne's proclamation of 29 April did not renew the prorogation of the last English parliament (set to expire on 30 April), then the last English parliament was legally defunct and the First British Parliament was new, and the triennial clock was reset. Although it seems that Marlborough's opinion prevailed,[2] it was not tested as ultimately the First British Parliament would sit through only one session and be dissolved in April 1708, before the triennial deadline.

The matter of continuity remains ambiguous in the records. The authoritative 19th-century parliamentary historian William Cobbett considered the First British Parliament a new and distinct parliament, and separated it from the Anne's last English parliament.[3] Collections of statute records treat it inconsistently, e.g. the Statutes at Large collections of both Pickering and Ruffhead label the last English session as "5 Anne", and the first British session as "6 Anne" (albeit dating its beginning on 23 October, the date of meeting, and not 29 April, the date of Anne's proclamation).[4] By contrast, the Statutes of the Realm (an official collection) does not differentiate the statute labels, and lists both sessions on the same roll, merged into one, with the last English statute labelled 6 Ann. c. 34 and the first British statute labeled 6 Ann. c. 35.[5]

The ambiguity of continuity mattered to the case of John Asgill, a member of parliament for Bramber, elected in 1705, who was arrested on 12 June 1707 and imprisoned at Fleet Prison for debt. Although this was in the interval between the closure of the English parliament and the opening of the British one, Asgill appealed to parliamentary immunity from arrest on the grounds that he was a member of a current parliament. Asgill's appeal was debated in the British House of Commons shortly after opening. Although the House ended up agreeing, on 16 December, that Asgill had retained immunity in that period ("ought to have the privilege"), they did not explain why, nor declare precisely of which parliament he was a member at the time of his arrest.[6] Nonetheless, two days after ordering his release, the House voted to expel Asgill on different grounds (authoring a blasphemous book).[7]

Dates of the Parliament

Election: On 29 April 1707, the Parliament of Great Britain was proclaimed. The members of the last English House of Commons had been elected between 7 May 1705 and 6 June 1705. The last general election in pre-Union Scotland was in the Autumn of 1702. The Parliament of Scotland met between 6 May 1703 and 25 March 1707.

First meeting and maximum legal term: Parliament first met on 23 October 1707. If continuity is accepted, then the parliament was due to expire, if not sooner dissolved, at the end of the term of three years from the first meeting of the last Parliament of England; which would have been on 14 June 1708.

Dissolution: The first and only session the First British Parliament was prorogued on 1 April 1708. During the recess, it was prorogued again on 13 April and, two days later, on 15 April, parliament was dissolved by proclamation and new writs issued for summons and elections to a new parliament.[8]

Party composition

The concept of party was much looser than it later became. Neither contemporaries or subsequent historians could be absolutely certain of who belonged in which category, however some estimates can be made.

Ambitious noble and gentry families formed themselves into connections of relatives and hangers on. Connections grouped themselves into factions, usually supporting a prominent public figure seeking royal favour and office for himself and his associates. Factions were usually of a Whig or Tory tendency.

Cross-cutting the Whig and Tory division was the Court and Country one. Court Party supporters were those who tended to support the Queen's ministers. Country Party men were inclined to oppose all Ministries.

The party divisions in Scotland were similar to those in England and Wales (although more inclined to Court and Whig than Country and Tory attitudes). Scottish politics also included the Squadrone Volante. This was a group, named after a type of cavalry formation, which had first opposed the Union but developed into moderate supporters of it.

An estimate of the composition of the Parliament of England, after the 1705 election, was Tory 267 and Whig 246.

Summary of the members of Parliament

Key to categories in the following tables: Boro': Borough constituencies, Shire: County constituencies, Univ.: University constituencies, Co.: Co-opted constituency (elected by Parliament), No.: number of constituencies, MPs: number of Members of Parliament, Total consts: Total constituencies

Scotland is being counted here as a single constituency, as all 45 MPs were elected by the last Parliament of Scotland. Monmouthshire (with one borough and two county members) is included in Wales for the purposes of this article, although at this period it was often regarded as part of England.

| Country | Constituencies | Members | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boro' | Shire | Univ. | Co. | Total | Boro' | Shire | Univ. | Scots | Total | |

| 202 | 39 | 2 | — | 243 | 404 | 78 | 4 | — | 486 | |

| Wales | 13 | 13 | — | — | 26 | 13 | 14 | — | — | 27 |

| — | — | — | 1 | 1 | — | — | — | 45 | 45 | |

| Total | 215 | 52 | 2 | 1 | 270 | 417 | 92 | 4 | 45 | 558 |

| Country | Borough constituencies |

Shire and county constituencies |

University const'ies |

Co-opted const'y |

Total consts |

Total MPs | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 MP | 2 MPs | 4 MPs | No. | MPs | 1 MP | 2 MPs | No. | MPs | 2 MPs | MPs | 45 MPs | MPs | |||

| 4 | 196 | 2 | 202 | 404 | — | 39 | 39 | 78 | 2 | 4 | — | — | 243 | 486 | |

| Wales | 13 | — | — | 13 | 13 | 12 | 1 | 13 | 14 | — | — | — | — | 26 | 27 |

| — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | 45 | 1 | 45 | |

| Total | 17 | 196 | 2 | 215 | 417 | 12 | 40 | 52 | 92 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 45 | 270 | 558 |

Speakers and Government

Sidney Godolphin, Lord Treasurer

Sidney Godolphin, Lord Treasurer William Cowper, Lord Chancellor, Speaker of Lords

William Cowper, Lord Chancellor, Speaker of Lords

William Cowper (Lord Cowper), Lord Keeper of the Seal since October 1705, was elevated by Queen Anne on 4 May 1707 to Lord Chancellor and thus sat on the woolsack as the first Lord Speaker of the House of Lords of Great Britain.[9]

On 23 October 1707, John Smith (1655–1723), MP (Whig) for Andover since 1695, was elected the first Speaker of the House of Commons of Great Britain. Smith had been the Speaker of the House of Commons of England since 1705.[10]

When this Parliament took place no office of Prime Minister existed. Government in 1707 has been characterized as a "no party" coalition, a mixture of Tory and Whig ministers, led by a triumvirate consisting of Sidney Godolphin, 1st Earl of Godolphin (the Lord High Treasurer and dominant minister at the time), Robert Harley (Secretary of State) and John Churchill (Duke of Marlborough) (Master-General of the Ordnance) (see Godolphin–Marlborough ministry for more information). There was a severe political crisis in February 1708, when Anne tried to get to get rid of Godolphin (although a Tory, Godolphin was increasingly reliant on the Junto Whigs in parliament, whom Anne could not brook). Anne tried to impose a new slate of ministers headed by Harley, but Godolphin and Marlborough joined forces to resist it, and it was Harley who got ejected instead. Godolphin remained in office in a reconstructed coalition ministry.

The War of the Spanish Succession, which had begun in earnest in 1702, was still on-going for the duration of this parliament, and much of the parliamentary debate during the session relates to the war. Parliament was still in session when James Francis Stuart ("Old Pretender"), with French support, attempted a failed Jacobite landing in Scotland in March 1708. Among the notable acts of the session was the passage of an act (6 Anne c.6) abolishing the Privy Council of Scotland, and thus establishing a single privy council for both England and Scotland. There were other acts to extend jurisdiction of English institutions (e.g. Courts of Exchequer) to Scotland and formalize the procedures for election of Scottish peers and MPs. It also approved the merger of the East India companies and reinstated a single monopoly (which had been broken in 1698) in return for a lump sum fee (6 Anne c.17). It also passed an act (6 Anne c.32) regulating the positions and elections for governor, directors, etc. of the Bank of England (est. 1694).

See also

References

- ↑ "I think it expedient that the Lords of parliament of England, and Commons of the present parliament of England, should be the members of the respective houses of the first parliament of Great Britain, for and on the behalf of England; and therefore I intend within the time limited, to publish a proclamation for the purpose, pursuant to the powers given me by the acts of parliament of both kingdoms, ratifying the treaty of Union" (Anne's speech of 24 April 1707, as published in Cobbett (1810) Parliamentary History of Great Britain, vol. 6: pp. 580–81).

- ↑ Cobbett (1810: pp. 588–89)

- ↑ Cobbett (1810, vol. 6, p. 589).

- ↑ Pickering's Statutes at Large, vol. 11, p. 290

- ↑ See Chronological Table and Index of the Statutes, 1890: p. 76.

- ↑ J. Hatsell (1818) Precedents of Proceedings in the House of Commons, vol. 2, p. 41

- ↑ Cobbett (1810:p. 601)

- ↑ Cobbett (1810: p. 732)

- ↑ Cobbett, 1810: v. 6, p. 909

- ↑ Cobbett, 1810, v.6, p. 589

Sources

- The Treaty of Union of Scotland and England 1707, edited by George S. Pryde (Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd 1950)

- British Historical Facts 1688–1760, by Chris Cook and John Stevenson (The Macmillan Press 1988)