Scotland (Scots: Scotland; Scottish Gaelic: Alba) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjacent islands, principally in the archipelagos of the Hebrides and the Northern Isles. To the south-east Scotland has its only land border, which is 96 miles (154 km) long and shared with England; the country is surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, the North Sea to the north-east and east, and the Irish Sea to the south. The population in 2022 was 5,436,600 and accounts for 8% of the population of the UK.[10] Edinburgh is the capital and Glasgow is the largest of the cities of Scotland.

The Kingdom of Scotland emerged in the 9th century. In 1603, James VI inherited England and Ireland, forming a personal union of the three kingdoms. On 1 May 1707 Scotland and England combined to create the new Kingdom of Great Britain,[11][12] with the Parliament of Scotland subsumed into the Parliament of Great Britain. In 1999 a Scottish Parliament was re-established, and has devolved authority over many areas of domestic policy.[13] The country has a distinct legal system, educational system, and religious history from the rest of the UK, which have all contributed to the continuation of Scottish culture and national identity within the United Kingdom.[14] Scottish English and Scots are the most widely spoken languages in the country, existing on a dialect continuum with each other.[15] Scottish Gaelic speakers can be found all over Scotland, however is largely spoken natively by select communities on the Hebrides.[16] The number of Gaelic speakers numbers less than 2% of the total population, though state-sponsored revitalisation attempts have led to a growing community of second language speakers.[17]

The mainland of Scotland is broadly divided into three regions: the Highlands, a mountainous region in the north and north-west; the Lowlands, a flatter plain across the centre of the country; and the Southern Uplands, a hilly region along the southern border. The Highlands are the most mountainous region of the UK and contain its highest peak, Ben Nevis, at 4,413 feet (1,345 m).[10] The region also contains many lakes, called lochs; the term is also applied to the many saltwater inlets along the country's deeply indented western coastline. The geography of the many islands is varied. Some, such as Mull and Skye, are noted for their mountainous terrain, while the likes of Tiree and Coll are much flatter.

Etymology

Scotland comes from Scoti, the Latin name for the Gaels.[18] Philip Freeman has speculated on the likelihood of a group of raiders adopting a name from an Indo-European root, *skot, citing the parallel in Greek skotos (σκότος), meaning "darkness, gloom".[19] The Late Latin word Scotia ("land of the Gaels") was initially used to refer to Ireland,[20] and likewise in early Old English Scotland was used for Ireland.[21] By the 11th century at the latest, Scotia was being used to refer to (Gaelic-speaking) Scotland north of the River Forth, alongside Albania or Albany, both derived from the Gaelic Alba.[22] The use of the words Scots and Scotland to encompass all of what is now Scotland became common in the Late Middle Ages.[11]

History

Prehistory

Prehistoric Scotland, before the arrival of the Roman Empire, was culturally divergent.[23]

Repeated glaciations, which covered the entire land mass of modern Scotland, destroyed any traces of human habitation that may have existed before the Mesolithic period. It is believed the first post-glacial groups of hunter-gatherers arrived in Scotland around 12,800 years ago, as the ice sheet retreated after the last glaciation.[24] At the time, Scotland was covered in forests, had more bog-land, and the main form of transport was by water.[25]: 9 These settlers began building the first known permanent houses on Scottish soil around 9,500 years ago, and the first villages around 6,000 years ago. The well-preserved village of Skara Brae on the mainland of Orkney dates from this period. Neolithic habitation, burial, and ritual sites are particularly common and well preserved in the Northern Isles and Western Isles, where a lack of trees led to most structures being built of local stone.[26] Evidence of sophisticated pre-Christian belief systems is demonstrated by sites such as the Callanish Stones on Lewis and the Maes Howe on Orkney, which were built in the third millennium BC.[27]: 38

Early history

The first written reference to Scotland was in 320 BC by Greek sailor Pytheas, who called the northern tip of Britain "Orcas", the source of the name of the Orkney islands.[25]: 10

Most of modern Scotland was not incorporated into the Roman Empire, and Roman control over parts of the area fluctuated over a rather short period. The first Roman incursion into Scotland was in 79 AD, when Agricola invaded Scotland; he defeated a Caledonian army at the Battle of Mons Graupius in 83 AD.[25]: 12 After the Roman victory, Roman forts were briefly set along the Gask Ridge close to the Highland line, but by three years after the battle, the Roman armies had withdrawn to the Southern Uplands.[28] Remains of Roman forts established in the 1st century have been found as far north as the Moray Firth.[29] By the reign of the Roman emperor Trajan (r. 98–117), Roman control had lapsed to Britain south of a line between the River Tyne and the Solway Firth.[30] Along this line, Trajan's successor Hadrian (r. 117–138) erected Hadrian's Wall in northern England[25]: 12 and the Limes Britannicus became the northern border of the Roman Empire.[31][32] The Roman influence on the southern part of the country was considerable, and they introduced Christianity to Scotland.[25]: 13–14 [27]: 38

The Antonine Wall was built from 142 at the order of Hadrian's successor Antoninus Pius (r. 138–161), defending the Roman part of Scotland from the unadministered part of the island, north of a line between the Firth of Clyde and the Firth of Forth.[33] The Roman invasion of Caledonia 208–210 was undertaken by emperors of the imperial Severan dynasty in response to the breaking of a treaty by the Caledonians in 197,[29] but permanent conquest of the whole of Great Britain was forestalled by Roman forces becoming bogged down in punishing guerrilla warfare and the death of the senior emperor Septimius Severus (r. 193–211) at Eboracum (York) after he was taken ill while on campaign. Although forts erected by the Roman army in the Severan campaign were placed near those established by Agricola and were clustered at the mouths of the glens in the Highlands, the Caledonians were again in revolt in 210–211 and these were overrun.[29]

To the Roman historians Tacitus and Cassius Dio, the Scottish Highlands and the area north of the River Forth was called Caledonia.[29] According to Cassius Dio, the inhabitants of Caledonia were the Caledonians and the Maeatae.[29] Other ancient authors used the adjective "Caledonian" to mean anywhere in northern or inland Britain, often mentioning the region's people and animals, its cold climate, its pearls, and a noteworthy region of wooded hills (Latin: saltus) which the 2nd century AD Roman philosopher Ptolemy, in his Geography, described as being south-west of the Beauly Firth.[29] The name Caledonia is echoed in the place names of Dunkeld, Rohallion, and Schiehallion.[29]

The Great Conspiracy constituted a seemingly coordinated invasion against Roman rule in Britain in the later 4th century, which included the participation of the Gaelic Scoti and the Caledonians, who were then known as Picts by the Romans. This was defeated by the comes Theodosius; but Roman military government was withdrawn from the island altogether by the early 5th century, resulting in the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain and the immigration of the Saxons to southeastern Scotland and the rest of eastern Great Britain.[30]

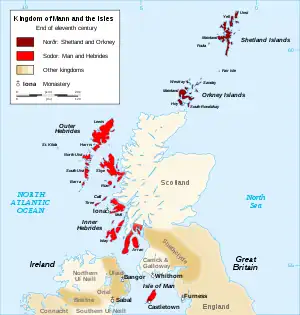

Kingdom of Scotland

Beginning in the sixth century, the area that is now Scotland was divided into three areas: Pictland, a patchwork of small lordships in central Scotland;[25]: 25–26 the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Northumbria, which had conquered southeastern Scotland;[25]: 18–20 and Dál Riata, which included territory in western Scotland and northern Ireland, and spread Gaelic language and culture into Scotland.[34] These societies were based on the family unit and had sharp divisions in wealth, although the vast majority were poor and worked full-time in subsistence agriculture. The Picts kept slaves (mostly captured in war) through the ninth century.[25]: 26–27

Gaelic influence over Pictland and Northumbria was facilitated by the large number of Gaelic-speaking clerics working as missionaries.[25]: 23–24 Operating in the sixth century on the island of Iona, Saint Columba was one of the earliest and best-known missionaries.[27]: 39 The Vikings began to raid Scotland in the eighth century. Although the raiders sought slaves and luxury items, their main motivation was to acquire land. The oldest Norse settlements were in northwest Scotland, but they eventually conquered many areas along the coast. Old Norse entirely displaced Pictish in the Northern Isles.[35]

In the ninth century, the Norse threat allowed a Gael named Kenneth I (Cináed mac Ailpín) to seize power over Pictland, establishing a royal dynasty to which the modern monarchs trace their lineage, and marking the beginning of the end of Pictish culture.[25]: 31–32 [36] The kingdom of Cináed and his descendants, called Alba, was Gaelic in character but existed on the same area as Pictland. By the end of the tenth century, the Pictish language went extinct as its speakers shifted to Gaelic.[25]: 32–33 From a base in eastern Scotland north of the River Forth and south of the River Spey, the kingdom expanded first southwards, into the former Northumbrian lands, and northwards into Moray.[25]: 34–35 Around the turn of the millennium, there was a centralization in agricultural lands and the first towns began to be established.[25]: 36–37

In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, much of Scotland was under the control of a single ruler. Initially, Gaelic culture predominated, but immigrants from France, England and Flanders steadily created a more diverse society, with the Gaelic language starting to be replaced by Scots; and a modern nation-state emerged from this. At the end of this period, war against England started the growth of a Scottish national consciousness.[37]: 37-39 [38]: ch 1 David I (1124–1153) and his successors centralised royal power[37]: 41–42 and united mainland Scotland, capturing regions such as Moray, Galloway, and Caithness, although he could not extend his power over the Hebrides, which had been ruled by various Scottish clans following the death of Somerled in 1164.[37]: 48–49 In 1266, Scotland fought the short but consequential Scottish-Norwegian War which saw the reclamation of the Hebrides after the strong defeat of King Haakon IV and his forces at the Battle of Largs.[39] Up until that point, the Hebrides had been under Norwegian Viking control for roughly 400 years and had developed a distinctive Norse–Gaelic culture that saw many Old Norse loanwords enter the Scottish Gaelic spoken by islanders, and through successive generations the Norse would become almost completely assimilated into Gaelic culture and the Scottish clan system. After the conflict, Scotland had to affirm Norwegian sovereignty of the Northern Isles, however they were later integrated into Scotland in the 15th century. Scandinavian culture in the form of the Norn language survived for a lot longer than in the Hebrides, and would strongly influence the local Scots dialect on Shetland and Orkney.[40] Later, a system of feudalism was consolidated, with both Anglo-Norman incomers and native Gaelic chieftains being granted land in exchange for serving the king.[37]: 53–54 The relationship with England was complex during this period: Scottish kings tried several times, asometimes with success, to exploit English political turmoil, followed by the longest period of peace between Scotland and England in the mediaeval period: from 1217–1296.[37]: 45-46

Wars of Scottish Independence

The death of Alexander III in March 1286 broke the succession line of Scotland's kings. Edward I of England arbitrated between various claimants for the Scottish crown. In return for surrendering Scotland's nominal independence, John Balliol was pronounced king in 1292.[37]: 47 [41] In 1294, Balliol and other Scottish lords refused Edward's demands to serve in his army against the French. Scotland and France sealed a treaty on 23 October 1295, known as the Auld Alliance. War ensued, and John was deposed by Edward who took personal control of Scotland. Andrew Moray and William Wallace initially emerged as the principal leaders of the resistance to English rule in the Wars of Scottish Independence,[42] until Robert the Bruce was crowned king of Scotland in 1306.[43] Victory at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314 proved the Scots had regained control of their kingdom. In 1320 the world's first documented declaration of independence, the Declaration of Arbroath, won the support of Pope John XXII, leading to the legal recognition of Scottish sovereignty by the English Crown. [44]: 70, 72

A civil war between the Bruce dynasty and their long-term rivals of the House of Comyn and House of Balliol lasted until the middle of the 14th century. Although the Bruce faction was successful, David II's lack of an heir allowed his half-nephew Robert II, the Lord High Steward of Scotland, to come to the throne and establish the House of Stewart.[44]: 77 The Stewarts ruled Scotland for the remainder of the Middle Ages. The country they ruled experienced greater prosperity from the end of the 14th century through the Scottish Renaissance to the Reformation,[45]: 93 despite the effects of the Black Death in 1349[44]: 76 and increasing division between Highlands and Lowlands.[44]: 78 Multiple truces reduced warfare on the southern border.[44]: 76, 83

Union of the Crowns

_-_James_VI_and_I_(1566%E2%80%931625)%252C_King_of_Scotland_(1567%E2%80%931625)%252C_King_of_England_and_Ireland_(1603%E2%80%931625)_-_PG_2172_-_National_Galleries_of_Scotland.jpg.webp)

The Treaty of Perpetual Peace was signed in 1502 by James IV of Scotland and Henry VII of England. James married Henry's daughter, Margaret Tudor.[46] James invaded England in support of France under the terms of the Auld Alliance and became the last monarch in Great Britain to die in battle, at Flodden in 1513.[47] The war with England during the minority years of Mary, Queen of Scots between 1543 and 1551 is known as the Rough Wooing.[48] In 1560, the Treaty of Edinburgh brought an end to the Siege of Leith and recognized the Protestant Elizabeth I as Queen of England.[45]: 112 The Parliament of Scotland met and immediately adopted the Scots Confession, which signalled the Scottish Reformation's sharp break from papal authority and Roman Catholic teaching.[27]: 44 The Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots, was forced to abdicate in 1567.[49]

In 1603, James VI, King of Scots inherited the thrones of the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Ireland in the Union of the Crowns, and moved to London.[50] This was a so called personal union as despite having the same monarch the kingdoms retained their own parliaments, laws and other institutions. The first Union Jack was designed at James's behest, to be flown in addition to the St Andrew's Cross on Scots vessels at sea. James VI and I intended to create a single kingdom of Great Britain, but was thwarted in his attempt to do so by the Parliament of England, which supported the wrecking proposal that a full legal union be sought instead, a proposal to which the Scots Parliament would not assent, causing the king to withdraw the plan.[51]

With the exception of a short period under the Protectorate, Scotland remained a separate state in the 17th century, but there was considerable conflict between the crown and the Covenanters over the form of church government.[52]: 124 The military was strengthened, allowing the imposition of royal authority on the western Highland clans. The 1609 Statutes of Iona compelled the cultural integration of Hebridean clan leaders.[53]: 37–40 In 1641 and again in 1643, the Parliament of Scotland unsuccessfully sought a union with England which was "federative" and not "incorporating", in which Scotland would retain a separate parliament.[54] The issue of union split the parliament in 1648.[54]

After the execution of the Scottish king at Whitehall in 1649, amid the Wars of the Three Kingdoms and its events in Scotland, Oliver Cromwell, the victorious Lord Protector, imposed the British Isles' first written constitution – the Instrument of Government – on Scotland in 1652 as part of the republican Commonwealth of England, Scotland, and Ireland.[54] The Protectorate Parliament was the first Westminster parliament to include representatives nominally from Scotland. The monarchy of the House of Stuart was resumed with the Restoration in Scotland in 1660. The Parliament of Scotland sought a commercial union with England in 1664; the proposal was rejected in 1668.[54] In 1670 the Parliament of England rejected a proposed political union with Scotland.[54] English proposals along the same lines were abandoned in 1674 and in 1685.[54] The Scots Parliament rejected proposals for a political union with England in 1689.[54] Jacobitism, the political support for the exiled Catholic Stuart dynasty, remained a threat to the security of the British state under the Protestant House of Orange and the succeeding House of Hanover until the defeat of the Jacobite rising of 1745.[54] In 1698, the Company of Scotland attempted a project to secure a trading colony on the Isthmus of Panama. Almost every Scottish landowner who had money to spare is said to have invested in the Darien scheme.[55][56]

Treaty of Union

After another proposal from the English House of Lords was rejected in 1695, and a further Lords motion was voted down in the House of Commons in 1700, the Parliament of Scotland again rejected union in 1702.[54] The failure of the Darien Scheme bankrupted the landowners who had invested, though not the burghs. Nevertheless, the nobles' bankruptcy, along with the threat of an English invasion, played a leading role in convincing the Scots elite to back a union with England.[55][56] On 22 July 1706, the Treaty of Union was agreed between representatives of the Scots Parliament and the Parliament of England. The following year, twin Acts of Union were passed by both parliaments to create the united Kingdom of Great Britain with effect from 1 May 1707[57] with popular opposition and anti-union riots in Edinburgh, Glasgow, and elsewhere.[58][59] The union also created the Parliament of Great Britain, which succeeded both the Parliament of Scotland and the Parliament of England, which rejected proposals from the Parliament of Ireland that the third kingdom be incorporated in the union.[54]

With trade tariffs with England abolished, trade blossomed, especially with Colonial America. The clippers belonging to the Glasgow Tobacco Lords were the fastest ships on the route to Virginia. Until the American War of Independence in 1776, Glasgow was the world's premier tobacco port, dominating world trade.[60] The disparity between the wealth of the merchant classes of the Scottish Lowlands and the ancient clans of the Scottish Highlands grew, amplifying centuries of division.

The deposed Jacobite Stuart claimants had remained popular in the Highlands and north-east, particularly among non-Presbyterians, including Roman Catholics and Episcopalian Protestants. Two major Jacobite risings launched in 1715 and 1745 failed to remove the House of Hanover from the British throne. The threat of the Jacobite movement to the United Kingdom and its monarchs effectively ended at the Battle of Culloden, Great Britain's last pitched battle.

In the Highlands, clan chiefs gradually started to think of themselves more as commercial landlords than leaders of their people. These social and economic changes included the first phase of the Highland Clearances and, ultimately, the demise of clanship.[61]: 32–53, passim

Industrial age and the Scottish Enlightenment

The Scottish Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution turned Scotland into an intellectual, commercial and industrial powerhouse[62] — so much so Voltaire said "We look to Scotland for all our ideas of civilisation."[63] With the demise of Jacobitism and the advent of the Union, thousands of Scots, mainly Lowlanders, took up numerous positions of power in politics, civil service, the army and navy, trade, economics, colonial enterprises and other areas across the nascent British Empire. Historian Neil Davidson notes "after 1746 there was an entirely new level of participation by Scots in political life, particularly outside Scotland." Davidson also states "far from being 'peripheral' to the British economy, Scotland – or more precisely, the Lowlands – lay at its core."[64]

The Scottish Reform Act 1832 increased the number of Scottish MPs and widened the franchise to include more of the middle classes.[65] From the mid-century, there were increasing calls for Home Rule for Scotland and the post of Secretary of State for Scotland was revived.[66] Towards the end of the century Prime Ministers of Scottish descent included William Gladstone,[67] and the Earl of Rosebery.[68] In the late 19th century the growing importance of the working classes was marked by Keir Hardie's success in the Mid Lanarkshire by-election, 1888, leading to the foundation of the Scottish Labour Party, which was absorbed into the Independent Labour Party in 1895, with Hardie as its first leader.[69] Glasgow became one of the largest cities in the world and known as "the Second City of the Empire" after London.[70] After 1860, the Clydeside shipyards specialised in steamships made of iron (after 1870, made of steel), which rapidly replaced the wooden sailing vessels of both the merchant fleets and the battle fleets of the world. It became the world's pre-eminent shipbuilding centre.[71] The industrial developments, while they brought work and wealth, were so rapid that housing, town-planning, and provision for public health did not keep pace with them, and for a time living conditions in some of the towns and cities were notoriously bad, with overcrowding, high infant mortality, and growing rates of tuberculosis.[72]

While the Scottish Enlightenment is traditionally considered to have concluded toward the end of the 18th century,[73] disproportionately large Scottish contributions to British science and letters continued for another 50 years or more, thanks to such figures as the physicists James Clerk Maxwell and Lord Kelvin, and the engineers and inventors James Watt and William Murdoch, whose work was critical to the technological developments of the Industrial Revolution throughout Britain.[74] In literature, the most successful figure of the mid-19th century was Walter Scott. His first prose work, Waverley in 1814, is often called the first historical novel.[75] It launched a highly successful career that probably more than any other helped define and popularise Scottish cultural identity.[76] In the late 19th century, a number of Scottish-born authors achieved international reputations, such as Robert Louis Stevenson, Arthur Conan Doyle, J. M. Barrie and George MacDonald.[77] Scotland also played a major part in the development of art and architecture. The Glasgow School, which developed in the late 19th century, and flourished in the early 20th century, produced a distinctive blend of influences including the Celtic Revival the Arts and Crafts movement, and Japonism, which found favour throughout the modern art world of continental Europe and helped define the Art Nouveau style. Proponents included architect and artist Charles Rennie Mackintosh.[78]

World wars and Scotland Act 1998

Scotland played a major role in the British effort in the First World War. It especially provided manpower, ships, machinery, fish and money.[79] With a population of 4.8 million in 1911, Scotland sent over half a million men to the war, of whom over a quarter died in combat or from disease, and 150,000 were seriously wounded.[80] Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig was Britain's commander on the Western Front. The war saw the emergence of a radical movement called "Red Clydeside" led by militant trades unionists. Formerly a Liberal stronghold, the industrial districts switched to Labour by 1922, with a base among the Irish Catholic working-class districts. Women were especially active in building neighbourhood solidarity on housing issues. The "Reds" operated within the Labour Party with little influence in Parliament and the mood changed to passive despair by the late 1920s.[81]

During the Second World War, Scotland was targeted by Nazi Germany largely due to its factories, shipyards, and coal mines.[82] Cities such as Glasgow and Edinburgh were targeted by German bombers, as were smaller towns mostly located in the central belt of the country.[82] Perhaps the most significant air-raid in Scotland was the Clydebank Blitz of March 1941, which intended to destroy naval shipbuilding in the area.[83] 528 people were killed and 4,000 homes totally destroyed.[83] Perhaps Scotland's most unusual wartime episode occurred in 1941 when Rudolf Hess flew to Renfrewshire, possibly intending to broker a peace deal through the Duke of Hamilton.[84] Before his departure from Germany, Hess had given his adjutant, Karlheinz Pintsch, a letter addressed to Adolf Hitler that detailed his intentions to open peace negotiations with the British. Pintsch delivered the letter to Hitler at the Berghof around noon on 11 May.[85] Albert Speer later said Hitler described Hess's departure as one of the worst personal blows of his life, as he considered it a personal betrayal.[86] Hitler worried that his allies, Italy and Japan, would perceive Hess's act as an attempt by Hitler to secretly open peace negotiations with the British.

After 1945, Scotland's economic situation worsened due to overseas competition, inefficient industry, and industrial disputes.[87] Only in recent decades has the country enjoyed something of a cultural and economic renaissance. Economic factors contributing to this recovery included a resurgent financial services industry, electronics manufacturing, (see Silicon Glen),[88] and the North Sea oil and gas industry.[89] The introduction in 1989 by Margaret Thatcher's government of the Community Charge (widely known as the Poll Tax) one year before the rest of Great Britain,[90] contributed to a growing movement for Scottish control over domestic affairs.[91]

Following a referendum on devolution proposals in 1997, the Scotland Act 1998[92] was passed by the British Parliament, which established a devolved Scottish Parliament and Scottish Government with responsibility for most laws specific to Scotland.[93] The Scottish Parliament was reconvened in Edinburgh on 4 July 1999.[94] The first to hold the office of first minister of Scotland was Donald Dewar, who served until his sudden death in 2000.[95]

21st century

The Scottish Parliament Building at Holyrood opened in October 2004 after lengthy construction delays and running over budget.[96] The Scottish Parliament's form of proportional representation (the additional member system) resulted in no one party having an overall majority for the first three Scottish parliament elections.

The pro-independence Scottish National Party led by Alex Salmond achieved an overall majority in the 2011 election, winning 69 of the 129 seats available.[97] The success of the SNP in achieving a majority in the Scottish Parliament paved the way for the September 2014 referendum on Scottish independence. The majority voted against the proposition, with 55% voting no to independence.[98] More powers, particularly in relation to taxation, were devolved to the Scottish Parliament after the referendum, following cross-party talks in the Smith Commission.

Since the 2014 referendum, events such as the UK leaving the European Union, despite a majority of voters in Scotland voting to remain a member, has led to calls for a second referendum on independence. In 2022, the Lord Advocate Dorothy Bain argued the case for the Scottish Government to hold another referendum on the issue, with the Supreme Court later ruling against the argument.[99] Following the Supreme Court decision, the Scottish Government stated that it wished to make amendments to the Scotland Act 1998 that would allow a referendum to be held in 2023.[100]

Geography and natural history

The mainland of Scotland comprises the northern third of the land mass of the island of Great Britain, which lies off the north-west coast of Continental Europe. The total area is 30,977 square miles (80,231 km2) with a land area of 30,078 square miles (77,901 km2),[4] comparable to the size of the Czech Republic. Scotland's only land border is with England, and runs for 96 miles (154 km) between the basin of the River Tweed on the east coast and the Solway Firth in the west. The Atlantic Ocean borders the west coast and the North Sea is to the east. The island of Ireland lies only 13 miles (21 km) from the south-western peninsula of Kintyre;[101] Norway is 190 miles (305 km) to the east and the Faroe Islands, 168 miles (270 km) to the north.

The territorial extent of Scotland is generally that established by the 1237 Treaty of York between Scotland and the Kingdom of England[102] and the 1266 Treaty of Perth between Scotland and Norway.[12] Important exceptions include the Isle of Man, which having been lost to England in the 14th century is now a crown dependency outside of the United Kingdom; the island groups Orkney and Shetland, which were acquired from Norway in 1472;[103] and Berwick-upon-Tweed, lost to England in 1482

The geographical centre of Scotland lies a few miles from the village of Newtonmore in Badenoch.[104] Rising to 4,413 feet (1,345 m) above sea level, Scotland's highest point is the summit of Ben Nevis, in Lochaber, while Scotland's longest river, the River Tay, flows for a distance of 117 miles (188 km).[10]

Geology and geomorphology

The whole of Scotland was covered by ice sheets during the Pleistocene ice ages and the landscape is much affected by glaciation. From a geological perspective, the country has three main sub-divisions.

The Highlands and Islands lie to the north and west of the Highland Boundary Fault, which runs from Arran to Stonehaven. This part of Scotland largely comprises ancient rocks from the Cambrian and Precambrian, which were uplifted during the later Caledonian orogeny. It is interspersed with igneous intrusions of a more recent age, remnants of which formed mountain massifs such as the Cairngorms and Skye Cuillins. In north-eastern mainland Scotland weathering of rock that occurred before the Last Ice Age has shaped much of the landscape.[105]

A significant exception to the above are the fossil-bearing beds of Old Red Sandstones found principally along the Moray Firth coast. The Highlands are generally mountainous and the highest elevations in the British Isles are found here. Scotland has over 790 islands divided into four main groups: Shetland, Orkney, and the Inner Hebrides and Outer Hebrides. There are numerous bodies of freshwater including Loch Lomond and Loch Ness. Some parts of the coastline consist of machair, a low-lying dune pasture land.

The Central Lowlands is a rift valley mainly comprising Paleozoic formations. Many of these sediments have economic significance for it is here that the coal and iron bearing rocks that fuelled Scotland's industrial revolution are found. This area has also experienced intense volcanism, Arthur's Seat in Edinburgh being the remnant of a once much larger volcano. This area is relatively low-lying, although even here hills such as the Ochils and Campsie Fells are rarely far from view.

The Southern Uplands are a range of hills almost 125 miles (200 km) long, interspersed with broad valleys. They lie south of a second fault line (the Southern Uplands fault) that runs from Girvan to Dunbar.[106][107][108] The geological foundations largely comprise Silurian deposits laid down some 400 to 500 million years ago. The high point of the Southern Uplands is Merrick with an elevation of 843 m (2,766 ft).[11][109][110][111] The Southern Uplands is home to Scotland's highest village, Wanlockhead (430 m or 1,411 ft above sea level).[108]

Climate

The climate of most of Scotland is temperate and oceanic, and tends to be very changeable. As it is warmed by the Gulf Stream from the Atlantic, it has much milder winters (but cooler, wetter summers) than areas on similar latitudes, such as Labrador, southern Scandinavia, the Moscow region in Russia, and the Kamchatka Peninsula on the opposite side of Eurasia. Temperatures are generally lower than in the rest of the UK, with the temperature of −27.2 °C (−17.0 °F) recorded at Braemar in the Grampian Mountains, on 11 February 1895, the coldest ever recorded anywhere in the UK.[112] Winter maxima average 6 °C (43 °F) in the Lowlands, with summer maxima averaging 18 °C (64 °F). The highest temperature recorded was 35.1 °C (95.2 °F) at Floors Castle, Scottish Borders on 19 July 2022.[113]

The west of Scotland is usually warmer than the east, owing to the influence of Atlantic ocean currents and the colder surface temperatures of the North Sea. Tiree, in the Inner Hebrides, is one of the sunniest places in the country: it had more than 300 hours of sunshine in May 1975.[114] Rainfall varies widely across Scotland. The western highlands of Scotland are the wettest, with annual rainfall in a few places exceeding 3,000 mm (120 in).[115] In comparison, much of lowland Scotland receives less than 800 mm (31 in) annually.[116] Heavy snowfall is not common in the lowlands, but becomes more common with altitude. Braemar has an average of 59 snow days per year,[117] while many coastal areas average fewer than 10 days of lying snow per year.[116]

Flora and fauna

Scotland's wildlife is typical of the north-west of Europe, although several of the larger mammals such as the lynx, brown bear, wolf, elk and walrus were hunted to extinction in historic times. There are important populations of seals and internationally significant nesting grounds for a variety of seabirds such as gannets.[118] The golden eagle is something of a national icon.[119]

On the high mountain tops, species including ptarmigan, mountain hare and stoat can be seen in their white colour phase during winter months.[120] Remnants of the native Scots pine forest exist[121] and within these areas the Scottish crossbill, the UK's only endemic bird species and vertebrate, can be found alongside capercaillie, Scottish wildcat, red squirrel and pine marten.[122][123][124] Various animals have been re-introduced, including the white-tailed eagle in 1975, the red kite in the 1980s,[125][126] and there have been experimental projects involving the beaver and wild boar. Today, much of the remaining native Caledonian Forest lies within the Cairngorms National Park and remnants of the forest remain at 84 locations across Scotland. On the west coast, remnants of ancient Celtic Rainforest still remain, particularly on the Taynish peninsula in Argyll, these forests are particularly rare due to high rates of deforestation throughout Scottish history.[127][128]

The flora of the country is varied incorporating both deciduous and coniferous woodland as well as moorland and tundra species. Large-scale commercial tree planting and management of upland moorland habitat for the grazing of sheep and field sport activities like deer stalking and driven grouse shooting impacts the distribution of indigenous plants and animals.[129] The UK's tallest tree is a grand fir planted beside Loch Fyne, Argyll in the 1870s, and the Fortingall Yew may be 5,000 years old and is probably the oldest living thing in Europe.[130][131][132] Although the number of native vascular plants is low by world standards, Scotland's substantial bryophyte flora is of global importance.[133][134]

Demographics

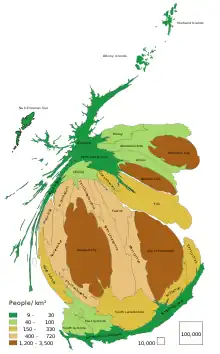

Population

During the 1820s, many Scots migrated from Scotland to countries such as Australia, the United States and Canada, principally from the Highlands which remained poor in comparison to elsewhere in Scotland.[135] The Highlands was the only part of mainland Britain with a recurrent famine.[136] A small range of products were exported from the region, which had negligible industrial production and a continued population growth that tested the subsistence agriculture. These problems, and the desire to improve agriculture and profits were the driving forces of the ongoing Highland Clearances, in which many of the population of the Highlands suffered eviction as lands were enclosed, principally so that they could be used for sheep farming. The first phase of the clearances followed patterns of agricultural change throughout Britain. The second phase was driven by overpopulation, the Highland Potato Famine and the collapse of industries that had relied on the wartime economy of the Napoleonic Wars.[137]

The population of Scotland grew steadily in the 19th century, from 1,608,000 in the census of 1801 to 2,889,000 in 1851 and 4,472,000 in 1901.[138] Even with the development of industry, there were not enough good jobs. As a result, during the period 1841–1931, about 2 million Scots migrated to North America and Australia, and another 750,000 Scots relocated to England.[139] Caused by the advent of refrigeration and imports of lamb, mutton and wool from overseas, the 1870s brought with them a collapse of sheep prices and an abrupt halt in the previous sheep farming boom.[140]

In August 2012, the Scottish population reached an all-time high of 5.25 million people.[141] The reasons given were that, in Scotland, births were outnumbering the number of deaths, and immigrants were moving to Scotland from overseas. In 2011, 43,700 people moved from Wales, Northern Ireland or England to live in Scotland.[141] The most recent census in Scotland was conducted by the Scottish Government and the National Records of Scotland in March 2022.[142] The population of Scotland at the 2022 Census was 5,436,600, the highest ever,[143] beating the previous record of 5,295,400 at the 2011 Census. It was 5,062,011 at the 2001 Census.[144] An ONS estimate for mid-2021 was 5,480,000.[145] In the 2011 Census, 62% of Scotland's population stated their national identity as 'Scottish only', 18% as 'Scottish and British', 8% as 'British only', and 4% chose 'other identity only'.[146]

Over the course of its history, Scotland has long had a tradition of migration from Scotland and immigration into Scotland. In 2021, the Scottish Government released figures showing that an estimated 41,000 people had immigrated from other international countries into Scotland, while an average of 22,100 people had migrated from Scotland.[147] Scottish Government data from 2002 shows that by 2021, there had been a sharp increase in immigration to Scotland, with 2002 estimates standing at 27,800 immigrants. While immigration had increased from 2002, migration from Scotland had dropped, with 2002 estimates standing at 26,200 people migrating from Scotland.[148]

Urbanisation

Although Edinburgh is the capital of Scotland, the largest city is Glasgow, which has just over 584,000 inhabitants. The Greater Glasgow conurbation, with a population of almost 1.2 million, is home to nearly a quarter of Scotland's population.[149] The Central Belt is where most of the main towns and cities of Scotland are located, including Glasgow, Edinburgh, Dundee, and Perth. Scotland's only major city outside the Central Belt is Aberdeen. The Scottish Lowlands host 80% of the total population, where the Central Belt accounts for 3.5 million people.

In general, only the more accessible and larger islands remain inhabited. Currently, fewer than 90 remain inhabited. The Southern Uplands are essentially rural in nature and dominated by agriculture and forestry.[150][151] Because of housing problems in Glasgow and Edinburgh, five new towns were designated between 1947 and 1966. They are East Kilbride, Glenrothes, Cumbernauld, Livingston, and Irvine.[152]

The largest council area by population is Glasgow City, with Highland being the largest in terms of geographical area.

| Rank | Name | Council area | Pop. | Rank | Name | Council area | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Glasgow  Edinburgh |

1 | Glasgow | Glasgow City | 632,350 | 11 | Kirkcaldy | Fife | 50,370 |  Aberdeen  Dundee |

| 2 | Edinburgh | City of Edinburgh | 506,520 | 12 | Inverness | Highland | 47,790 | ||

| 3 | Aberdeen | Aberdeen | 198,590 | 13 | Perth | Perth and Kinross | 47,350 | ||

| 4 | Dundee | Dundee City | 148,210 | 14 | Kilmarnock | East Ayrshire | 46,970 | ||

| 5 | Paisley | Renfrewshire | 77,270 | 15 | Ayr | South Ayrshire | 46,260 | ||

| 6 | East Kilbride | South Lanarkshire | 75,310 | 16 | Coatbridge | North Lanarkshire | 43,950 | ||

| 7 | Livingston | West Lothian | 56,840 | 17 | Greenock | Inverclyde | 41,280 | ||

| 8 | Dunfermline | Fife | 54,990 | 18 | Glenrothes | Fife | 38,360 | ||

| 9 | Hamilton | South Lanarkshire | 54,480 | 19 | Stirling | Stirling | 37,910 | ||

| 10 | Cumbernauld | North Lanarkshire | 50,530 | 20 | Airdrie | North Lanarkshire | 36,390 | ||

Languages

Scotland has three officially recognised languages: English, Scots, and Scottish Gaelic.[154][155] Scottish Standard English, a variety of English as spoken in Scotland, is at one end of a bipolar linguistic continuum, with broad Scots at the other.[156] Scottish Standard English may have been influenced to varying degrees by Scots.[157][158] The 2011 census indicated that 63% of the population had "no skills in Scots".[159] Others speak Highland English. Gaelic is mostly spoken in the Western Isles, where a large proportion of people still speak it. Nationally, its use is confined to 1% of the population.[160] The number of Gaelic speakers in Scotland dropped from 250,000 in 1881 to 60,000 in 2008.[161]

Immigration since World War II has given Glasgow, Edinburgh, and Dundee small South Asian communities.[162] In 2011, there were an estimated 49,000 ethnically Pakistani people living in Scotland, making them the largest non-White ethnic group.[163] Since the enlargement of the European Union more people from Central and Eastern Europe have moved to Scotland, and the 2011 census indicated that 61,000 Poles live there.[163][164]

There are many more people with Scottish ancestry living abroad than the total population of Scotland. In the 2000 Census, 9.2 million Americans self-reported some degree of Scottish descent.[165] Ulster's Protestant population is mainly of lowland Scottish descent,[166] and it is estimated that there are more than 27 million descendants of the Scots-Irish migration now living in the US.[167][168] In Canada, the Scottish-Canadian community accounts for 4.7 million people.[169] About 20% of the original European settler population of New Zealand came from Scotland.[170]

Religion

Forms of Christianity have dominated religious life in what is now Scotland for more than 1,400 years.[171][172] In 2011 just over half (54%) of the Scottish population reported being a Christian while nearly 37% reported not having a religion.[173] Since the Scottish Reformation of 1560, the national church (the Church of Scotland, also known as The Kirk) has been Protestant in classification and Reformed in theology. Since 1689 it has had a Presbyterian system of church government independent from the state.[11] Its membership dropped just below 300,000 in 2020 (5% of the total population)[174][175][176] The Church operates a territorial parish structure, with every community in Scotland having a local congregation.

Scotland also has a significant Roman Catholic population, 19% professing that faith, particularly in Greater Glasgow and the north-west.[177] After the Reformation, Roman Catholicism in Scotland continued in the Highlands and some western islands like Uist and Barra, and it was strengthened during the 19th century by immigration from Ireland. Other Christian denominations in Scotland include the Free Church of Scotland, and various other Presbyterian offshoots. Scotland's third largest church is the Scottish Episcopal Church.[178]

There are an estimated 75,000 Muslims in Scotland (about 1.4% of the population),[173][179] and significant but smaller Jewish, Hindu and Sikh communities, especially in Glasgow.[179] The Samyé Ling monastery near Eskdalemuir, which celebrated its 40th anniversary in 2007, is the first Buddhist monastery in western Europe.[180]

Education

The Scottish education system has always had a characteristic emphasis on a broad education.[182] In the 15th century, the Humanist emphasis on education cumulated with the passing of the Education Act 1496, which decreed that all sons of barons and freeholders of substance should attend grammar schools to learn "perfyct Latyne", resulting in an increase in literacy among a male and wealthy elite.[183] In the Reformation, the 1560 First Book of Discipline set out a plan for a school in every parish, but this proved financially impossible.[184] In 1616 an act in Privy council commanded every parish to establish a school.[185] By the late seventeenth century there was a largely complete network of parish schools in the lowlands, but in the Highlands basic education was still lacking in many areas.[186] Education remained a matter for the church rather than the state until the Education (Scotland) Act 1872.[187]

Education in Scotland is the responsibility of the Scottish Government and is overseen by its executive agency Education Scotland.[188] The Curriculum for Excellence, Scotland's national school curriculum, presently provides the curricular framework for children and young people from age 3 to 18.[189] All 3- and 4-year-old children in Scotland are entitled to a free nursery place. Formal primary education begins at approximately 5 years old and lasts for 7 years (P1–P7); children in Scotland study National Qualifications of the Curriculum for Excellence between the ages of 14 and 18. The school leaving age is 16, after which students may choose to remain at school and study further qualifications. A small number of students at certain private schools may follow the English system and study towards GCSEs and A and AS-Levels instead.[190]

There are fifteen Scottish universities, some of which are among the oldest in the world.[191][192] The four universities founded before the end of the 16th century – the University of St Andrews, the University of Glasgow, the University of Aberdeen and the University of Edinburgh – are collectively known as the ancient universities of Scotland, all of which rank among the 200 best universities in the world in the THE rankings, with Edinburgh placing in the top 50.[193] Scotland had more universities per capita in QS' World University Rankings' top 100 in 2012 than any other nation.[194] The country produces 1% of the world's published research with less than 0.1% of the world's population, and higher education institutions account for 9% of Scotland's service sector exports.[195][196] Scotland's University Courts are the only bodies in Scotland authorised to award degrees.

Health

.jpg.webp)

Health care in Scotland is mainly provided by NHS Scotland, Scotland's public health care system. This was founded by the National Health Service (Scotland) Act 1947 (later repealed by the National Health Service (Scotland) Act 1978) that took effect on 5 July 1948 to coincide with the launch of the NHS in England and Wales. Prior to 1948, half of Scotland's landmass was already covered by state-funded health care, provided by the Highlands and Islands Medical Service.[198] Healthcare policy and funding is the responsibility of the Scottish Government's Health Directorates. In 2014, the NHS in Scotland had around 140,000 staff.[199]

The total fertility rate (TFR) in Scotland is below the replacement rate of 2.1 (the TFR was 1.73 in 2011[200]). The majority of births are to unmarried women (51.3% of births were outside of marriage in 2012[201]).

Life expectancy for those born in Scotland between 2012 and 2014 is 77.1 years for males and 81.1 years for females.[202] This is the lowest of any of the four countries of the UK.[202] The number of hospital admissions in Scotland for diseases such as cancer was 2,528 in 2002. Over the next ten years, by 2012, this had increased to 2,669.[203] Hospital admissions for other diseases, such as coronary heart disease (CHD) were lower, with 727 admissions in 2002, and decreasing to 489 in 2012.[203]

Government and politics

Scotland is part of the United Kingdom, a constitutional monarchy whose current sovereign is Charles III.[204] The monarchy uses a variety of styles, titles and other symbols specific to Scotland, most of which originated in the pre-Union Kingdom of Scotland. These include the Royal Standard of Scotland, the royal coat of arms, and the title Duke of Rothesay, which is traditionally given to the heir apparent. There are also distinct Scottish Officers of State and Officers of the Crown, and the Order of the Thistle, a chivalric order, is specific to the country.[205]

The Parliament of the United Kingdom and the Parliament of Scotland are the country's primary legislative bodies. The UK Parliament is sovereign and therefore has supremacy over the Scottish Parliament,[206] but generally restricts itself to legislating over reserved matters: primarily taxes, social security, defence, international relations, and broadcasting.[207] There is a convention the UK Parliament will not legislate over devolved matters without the Scottish Parliament's consent.[208] Scotland is represented in the House of Commons, the lower chamber of the UK Parliament, by 59 Members of Parliament (out of a total of 650).[209] They are elected to single-member constituencies under the first-past-the-post system of voting. The Scotland Office represents the British government in Scotland and represents Scottish interests within the government.[210] The Scotland Office is led by the Secretary of State for Scotland, who sits in the Cabinet of the United Kingdom.[211] The Conservative MP Alister Jack has held the position since July 2019.[211]

The Scottish Parliament is a unicameral legislature with 129 members (MSPs): 73 of them represent individual constituencies and are elected on a first-past-the-post system, and the other 56 are elected in eight different electoral regions by the additional member system. MSPs normally serve for a five-year period.[212] The largest party since the 2021 Scottish Parliament election, has been the Scottish National Party (SNP), which won 64 of the 129 seats.[213] The Scottish Conservatives, Scottish Labour, the Scottish Liberal Democrats and the Scottish Greens also have representation in the current Parliament.[213] The next Scottish Parliament election is due to be held on 7 May 2026.[214] The Scottish Government is led by the First Minister, who is nominated by MSPs and is typically the leader of the largest party in the Parliament. Other ministers are appointed by the first minister and serve at their discretion.[215] Since March 2023 the first minister has been Humza Yousaf, the leader of the SNP.

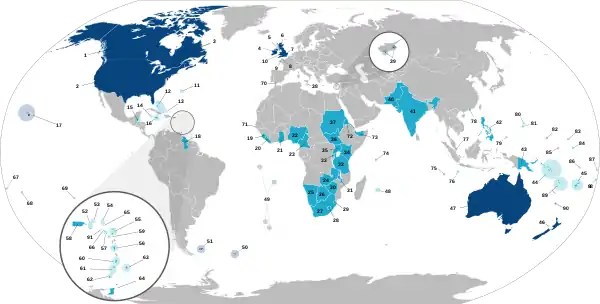

Diplomacy and relations

Within the UK, the First Minister is a member of the Heads of Government Council, the body which facilitates intergovernmental relations between the Scottish Government, UK Government, Welsh Government, and Northern Ireland Executive.[216] Foreign policy is a reserved matter and primarily the responsibility of the Foreign Office, a department of the UK Government.[217] Nevertheless, the Scottish Government may promote Scottish interests abroad and encourage foreign investment in Scotland.[218] The First Minister, Cabinet Secretary for Culture, Tourism and External Affairs,[219] and the Minister for International Development and Europe all have portfolios which include foreign affairs.[220][221]

Scotland's international network consists of two Scotland Houses, one in Brussels and the other in London, seven Scottish Government international offices, and over thirty Scottish Development International offices in other countries globally. Both Scotland Houses are independent Scottish Government establishments, whilst the seven Scottish Government international offices are based in British embassies or British High Commission offices.[222] The Scottish Government, along with the other devolved governments of the United Kingdom, pay the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office an annual charge to be able to access facilities and support in the Embassy or High Commission in which the Scottish international offices are based. The Scottish Government's international network allows Scottish Government ministers to engage with other international governments and bodies in relation to the government's policy objectives as well as that of Scottish businesses. Additionally, the international network of the Scottish Government acts as a mechanism to promote and strengthen the Scottish economy by creating opportunities for Scottish businesses to increase export sales of Scottish products, whilst working with their current, and any future, foreign investors to establish and maintain Scottish jobs in the goods sector.[222]

Scotland is a member of the British–Irish Council and the British–Irish Parliamentary Assembly, both of which are intended to foster collaboration between the legislative bodies of the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland.[223][224] The Scottish Government has a network of offices in Beijing, Berlin, Brussels, Copenhagen, Dublin, London, Ottawa, Paris, and Washington, D.C, which promote Scottish interests in their respective areas.[225] The nation has historic ties to France as a result of the 'Auld Alliance', a treaty signed between the Kingdom of Scotland and Kingdom of France in 1295 to discourage an English invasion of either country.[226] The alliance effectively ended in the sixteenth century, but the two countries continue to have a close relationship, with a Statement of Intent being signed in 2013 between the Scottish Government and the Government of France.[227] In 2004 the Scotland Malawi Partnership was established, which co-ordinates Scottish activities to strengthen existing links with Malawi, and in 2021, the Scottish Government and Government of Ireland signed the Ireland-Scotland Bilateral Review, committing both governments to increased levels of co–operation on areas such as diplomacy, economy and business.[222][228][229] Scotland also has historical and cultural ties with the Scandinavian countries.[230][231] Scottish Government policy advocates for stronger political relations with the Nordic and Baltic countries, which has resulted in some Nordic-inspired policies being adopted such as baby boxes.[232][233] Representatives from the Scottish Parliament attended the Nordic Council for the first time in 2022.[234]

Devolution and independence

Devolution—the granting of central government powers to a regional government[235]– gained increasing popularity as a policy in the United Kingdom the late twentieth century; it was described by John Smith, then Leader of the Labour Party, as the "settled will of the Scottish people".[236] The Scottish Parliament and Scottish Government were subsequently established under the Scotland Act 1998; the Act followed a successful referendum in 1997 which found majority support for both creating the Parliament and granting it limited powers to vary income tax.[237] The Act enabled the new institutions to legislate in all areas not explicitly reserved by the UK Parliament.[238]

Two more pieces of legislation, the Scotland Acts of 2012 and 2016, gave the Scottish Parliament further powers to legislate on taxation and social security;[239] the 2016 Act also gave the Scottish Government powers to manage the affairs of the Crown Estate in Scotland.[240] Conversely, the United Kingdom Internal Market Act 2020 constrains the Scottish Parliament's autonomy to regulate goods and services,[241][242] and the academic view is that this undermines devolution.[248]

The 2007 Scottish Parliament elections led to the Scottish National Party (SNP), which supports Scottish independence, forming a minority government. The new government established a "National Conversation" on constitutional issues, proposing a number of options such as increasing the powers of the Scottish Parliament, federalism, or a referendum on Scottish independence from the United Kingdom. The three main unionist opposition parties–Scottish Labour, the Scottish Conservatives, and the Scottish Liberal Democrats–created a separate commission to investigate the distribution of powers between devolved Scottish and UK-wide bodies while not considering independence.[249] In August 2009 the SNP proposed a bill to hold a referendum on independence in November 2010, but was defeated by opposition from all other major parties.[250][251][252]

The 2011 Scottish Parliament election resulted in an SNP an overall majority in the Scottish Parliament, and on 18 September 2014 a referendum on Scottish independence was held.[253] The referendum resulted in a rejection of independence, by 55.3% to 44.7%.[254][255] During the campaign, the three main parties in the British Parliament–the Conservatives, Labour, and the Liberal Democrats–pledged to extend the powers of the Scottish Parliament.[256][257] An all-party commission chaired by Robert Smith, Baron Smith of Kelvin was formed,[257] which led to the Scotland Act 2016.[258]

Following the European Union Referendum Act 2015, the 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum was held on 23 June 2016 on Britain's membership of the European Union. A majority in the United Kingdom voted to withdraw from the EU, while a majority within Scotland voted to remain a member.[259] The first minister, Nicola Sturgeon, announced the following day that as a result a new independence referendum was "highly likely".[260][259] On 31 January 2020, the United Kingdom formally withdrew from the European Union. Because constitutional affairs are reserved matters under the Scotland Act, the Scottish Parliament would again have to be granted temporary additional powers under Section 30 to hold a legally binding vote.[261][262][263]

Local government

For local government purposes Scotland is subdivided into 32 single-tier council areas.[264] The areas were established in 1996, and their councils are responsible for the provision of all local government services. Decisions are made by councillors, who are elected at local elections every five years. The leader of the council is typically a councillor from the party with the most seats; councils also have a civic head, typically called the provost or lord provost, who represents the council on ceremonial occasions and chairs council meetings.[265] Community Councils are informal organisations that represent smaller subdivisions within each council area.[266]

Police Scotland and the Scottish Fire and Rescue Service cover the entire country. For healthcare and postal districts, and a number of other governmental and non-governmental organisations such as the churches, there are other long-standing methods of subdividing Scotland for the purposes of administration.

There are eight cities in Scotland: Aberdeen, Dundee, Dunfermline, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Inverness, Stirling and Perth.[267] City status in the United Kingdom is conferred by the monarch through letters patent.[268]

Military

As part of the United Kingdom, the British Armed Forces are the armed forces of Scotland. Of the money spent on UK defence, about £3.3 billion can be attributed to Scotland as of 2018/2019.[269] Scotland had a long military tradition predating the Treaty of Union with England. Following the Treaty of Union in 1707, the Scots Army and Royal Scots Navy merged with their English counterparts to form the Royal Navy and the British Army, which together form part of the British Armed Forces.[270][271] The Atholl Highlanders, Europe's only remaining legal private army, did not join the Scots Army or Royal Scots Navy in merging with English armed forces, remaining a private army not under the command of the British Armed Forces.[272]

Numerous Scottish regiments have at various times existed in the British Army. Distinctively Scottish regiments in the British Army include the Scots Guards, the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards and the 154 (Scottish) Regiment RLC, an Army Reserve regiment of the Royal Logistic Corps. In 2006, as a result of the Delivering Security in a Changing World white paper, the Scottish infantry regiments in the Scottish Division were amalgamated to form the Royal Regiment of Scotland.[273] As a result of the Cameron–Clegg coalition's Strategic Defence and Security Review 2010, the Scottish regiments of the line in the British Army infantry, having previously formed the Scottish Division, were reorganised into the Scottish, Welsh and Irish Division in 2017. Before the formation of the Scottish Division, the Scottish infantry was organised into a Lowland Brigade and Highland Brigade.[274]

Because of their topography and perceived remoteness, parts of Scotland have housed many sensitive defence establishments.[275][276][277] Between 1960 and 1991, the Holy Loch was a base for the US fleet of Polaris ballistic missile submarines.[278] Today, Her Majesty's Naval Base Clyde, 25 miles (40 kilometres) north-west of Glasgow, is the base for the four Trident-armed Vanguard-class ballistic missile submarines that comprise the Britain's nuclear deterrent.

Scotland's Scapa Flow was the main base for the Royal Navy in the 20th century.[279] As the Cold War intensified in 1961, the United States deployed Polaris ballistic missiles, and submarines, in the Firth of Clyde's Holy Loch. Public protests from CND campaigners proved futile. The Royal Navy successfully convinced the government to allow the base because it wanted its own Polaris submarines, and it obtained them in 1963. The RN's nuclear submarine base opened with four Resolution-class Polaris submarines at the expanded Faslane Naval Base on the Gare Loch. The first patrol of a Trident-armed submarine occurred in 1994, although the US base was closed at the end of the Cold War.[280]

A single front-line Royal Air Force base is located in Scotland. RAF Lossiemouth, located in Moray, is the most northerly air defence fighter base in the United Kingdom and is home to four Eurofighter Typhoon combat aircraft squadrons, three Poseidon MRA1 squadrons, and a full–time, permanently based RAF Regiment squadron. [281]

Law and order

Scots law has a basis derived from Roman law,[282] combining features of both uncodified civil law, dating back to the Corpus Juris Civilis, and common law with medieval sources. The terms of the Treaty of Union with England in 1707 guaranteed the continued existence of a separate legal system in Scotland from that of England and Wales.[283] Prior to 1611, there were several regional law systems in Scotland, most notably Udal law in Orkney and Shetland, based on old Norse law. Various other systems derived from common Celtic or Brehon laws survived in the Highlands until the 1800s.[284] Scots law provides for three types of courts responsible for the administration of justice: civil, criminal and heraldic. The supreme civil court is the Court of Session, although civil appeals can be taken to the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom (or before 1 October 2009, the House of Lords). The High Court of Justiciary is the supreme criminal court in Scotland. The Court of Session is housed at Parliament House, in Edinburgh, which was the home of the pre-Union Parliament of Scotland with the High Court of Justiciary and the Supreme Court of Appeal currently located at the Lawnmarket. The sheriff court is the main criminal and civil court, hearing most cases. There are 49 sheriff courts throughout the country.[285] District courts were introduced in 1975 for minor offences and small claims. These were gradually replaced by Justice of the Peace Courts from 2008 to 2010.

For three centuries the Scots legal system was unique for being the only national legal system without a parliament. This ended with the advent of the Scottish Parliament in 1999, which legislates for devolved matters.[286] Many features within the system have been preserved. Within criminal law, the Scots legal system is unique in having three possible verdicts: "guilty", "not guilty" and "not proven".[287] Both "not guilty" and "not proven" result in an acquittal, typically with no possibility of retrial in accordance with the rule of double jeopardy. A retrial can hear new evidence at a later date that might have proven conclusive in the earlier trial at first instance, where the person acquitted subsequently admits the offence or where it can be proved that the acquittal was tainted by an attempt to pervert the course of justice. Scots juries, sitting in criminal cases, consist of fifteen jurors, which is three more than is typical in many countries.[288]

The Lord Advocate is the chief legal officer of the Scottish Government and the Crown in Scotland. The Lord Advocate is the head of the systems in Scotland for the investigation and prosecution of crime, the investigation of deaths as well as serving as the principal legal adviser to the Scottish Government and representing the government in legal proceedings.[289] They are the chief public prosecutor for Scotland and all prosecutions on indictment are conducted by the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service in the Lord Advocate's name on behalf of the Monarch.[289] The officeholder is one of the Great Officers of State of Scotland. The current Lord Advocate is Dorothy Bain, who was nominated by First Minister Nicola Sturgeon and appointed in June 2021.[290] The Lord Advocate is supported by the Solicitor General for Scotland.[291]

Since 2013, Scotland has had a unified police force known as Police Scotland. The Scottish Prison Service (SPS) manages the prisons in Scotland, which collectively house over 8,500 prisoners.[292] The Cabinet Secretary for Justice and Home Affairs is responsible for the Scottish Prison Service within the Scottish Government.

Economy

Scotland has a Western-style open mixed economy closely linked with the rest of the UK and the wider world. Scotland is one of the leading financial centres in Europe, and is the largest financial centre in the United Kingdom outside of London.[294] Edinburgh is the financial services centre of Scotland, with many large finance firms based there, including: Lloyds Banking Group, the Bank of Scotland, the Government-owned Royal Bank of Scotland and Standard Life.[295] Edinburgh was ranked 15th in the list of world financial centres in 2007, but fell to 37th in 2012, following damage to its reputation,[296] and in 2016 was ranked 56th out of 86.[297] Its status had returned to 17th by 2020.[298] Traditionally, the Scottish economy was dominated by heavy industry underpinned by shipbuilding in Glasgow, coal mining and steel industries. Petroleum related industries associated with the extraction of North Sea oil have also been important employers from the 1970s, especially in the north-east of Scotland. De-industrialisation during the 1970s and 1980s saw a shift from a manufacturing focus towards a more service-oriented economy. The Scottish National Investment Bank was established by the Scottish Government in 2020, which uses public money to fund commercial projects across Scotland with the hope that this seed capital will encourage further private investment, to help develop a fairer, more sustainable economy. £2 billion of taxpayers money was earmarked for the bank.[299]

In 2022, Scotland's gross domestic product (GDP), including offshore oil and gas, was estimated at £211.7 billion.[7] In 2021, Scottish exports in goods and services (excluding intra-UK trade) were estimated to be £50.1 billion.[300] Scotland's primary goods exports are mineral fuels, machinery and transport, and beverages and tobacco.[301] The country's largest export markets in goods are the European Union, Asia and Oceania, and North America.[301] Whisky is one of Scotland's more known goods of economic activity. Exports increased by 87% in the decade to 2012[302] and were valued at £4.3 billion in 2013, which was 85% of Scotland's food and drink exports.[303] It supports around 10,000 jobs directly and 25,000 indirectly.[304] It may contribute £400–682 million to Scotland, rather than several billion pounds, as more than 80% of whisky produced is owned by non-Scottish companies.[305] A briefing published in 2002 by the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) for the Scottish Parliament's Enterprise and Life Long Learning Committee stated that tourism accounted for up to 5% of GDP and 7.5% of employment.[306]

Scotland was one of the industrial powerhouses of Europe from the time of the Industrial Revolution onwards, being a world leader in manufacturing.[307] This left a legacy in the diversity of goods and services which Scotland produces, from textiles, whisky and shortbread to jet engines, buses, computer software, investment management and other related financial services.[308] In common with most other advanced industrialised economies, Scotland has seen a decline in the importance of both manufacturing industries and primary-based extractive industries. This has been combined with a rise in the service sector of the economy, which has grown to be the largest sector in Scotland.[309]

Income and poverty

.jpg.webp)

The average weekly income for workplace based employees in Scotland is £573,[310] and £576 for residence based employees.[310] Scotland has the third highest median gross salary in the United Kingdom at £26,007 and is higher than the overall UK average annual salary of £25,971.[311] With an average of £14.28, Scotland has the third highest median hourly rate (excluding overtime working hours) of any of the countries of the United Kingdom, and like the annual salary, is higher than the average UK figure as a whole.[311] The highest paid industries in Scotland tend of be in the utility electricity, gas and air conditioning sectors,[311] with industries like tourism, accommodation and food and drink tend to be the lowest paid.[311] The top local authority for pay by where people live is East Renfrewshire (£20.87 per hour).[311]

The top local authority for pay based on where people work are; East Ayrshire (£16.92 per hour). Scotland's cities commonly have the largest salaries in Scotland for where people work.[311] 2021/2022 date indicates that there were 2.6 million dwellings across Scotland, with 318,369 local authority dwellings.[312] Typical prices for a house in Scotland was £195,391 in August 2022.[313]

Between 2016 and 2020, the Scottish Government estimated that 10% of people in Scotland were in persistent poverty following housing costs, with similar rates of persistent poverty for children (10%), working-age adults (10%) and pensioners (11%).[314] Persistent child poverty rates had seen a relatively sharp drop, however, the accuracy of this was deemed to be questionable due to a number of various factors such as households re-entering the longitudinal sample allowing data gaps to be filled.[314] The Scottish Government introduced the Scottish Child Payment in 2021 for low income families with children under six years of age in an attempt to reduce child poverty rates, with families receiving a payment of roughly £1,040 per year.[315] As of October 2023, 10% of the Scottish population were estimated to be living in poverty.[316]

Currency

Although the Bank of England is the central bank for the UK, three Scottish clearing banks issue Sterling banknotes: the Bank of Scotland, the Royal Bank of Scotland and the Clydesdale Bank. The issuing of banknotes by retail banks in Scotland is subject to the Banking Act 2009, which repealed all earlier legislation under which banknote issuance was regulated, and the Scottish and Northern Ireland Banknote Regulations 2009.[317]

The value of the Scottish banknotes in circulation in 2013 was £3.8 billion, underwritten by the Bank of England using funds deposited by each clearing bank, under the Banking Act 2009, to cover the total value of such notes in circulation.[318]

Infrastructure and transportation

.jpg.webp)

Scotland has five international airports operating scheduled services to Europe, North America and Asia, as well as domestic services to England, Northern Ireland and Wales.[319] Highlands and Islands Airports operates eleven airports across the Highlands, Orkney, Shetland and the Western Isles, which are primarily used for short distance, public service operations, although Inverness Airport has a number of scheduled flights to destinations across the UK and mainland Europe.[320] Edinburgh Airport is currently Scotland's busiest airport handling over 13 million passengers in 2017.[321] It is also the UK's 6th busiest airport. The airline Loganair has its headquarters at Glasgow Airport and markets itself as Scotland's Airline.[322]

Network Rail owns and operates the fixed infrastructure assets of the railway system in Scotland, while the Scottish Government retains overall responsibility for rail strategy and funding in Scotland.[323] Scotland's rail network has 359 railway stations and around 1,710 miles (2,760 km) of track.[324] In 2018–19 there were 102 million passenger journeys on Scottish railways.[325]

The Scottish motorways and major trunk roads are managed by Transport Scotland. The remainder of the road network is managed by the Scottish local authorities in each of their areas.

Regular ferry services operate between the Scottish mainland and outlying islands. Ferries serving both the inner and outer Hebrides are principally operated by the state-owned enterprise Caledonian MacBrayne.[326][327] Services to the Northern Isles are operated by Serco. Other routes, such as southwest Scotland to Northern Ireland, are served by multiple companies.[328] DFDS Seaways operated a freight-only Rosyth – Zeebrugge ferry service, until a fire damaged the vessel DFDS were using.[329] A passenger service was also operated between 2002 and 2010.[330]

Science, technology and energy

Scotland's primary sources for energy are provided through renewable energy (61.8%), nuclear (25.7%) and fossil fuel generation (10.9%).[331] Whitelee Wind Farm is the largest on–shore wind farm in the United Kingdom, and was Europe's largest on–shore wind farm for a period of time.[332] Tidal power is an emerging source of energy in Scotland. The MeyGen tidal stream energy plant in the north of the country is claimed to be the largest tidal stream energy project in the world.[333] In Scotland, 98.6% of all electricity used was from renewable sources. This is minus net exports.[331] Between October 2021 and September 2022 63.1% of all electricity generated in Scotland was from renewable sources, 83.6% was classed as low carbon and 14.5% was from fossil fuels.[334] The Scottish Government has a target to have the equivalent of 50% of the energy for Scotland's heat, transport and electricity consumption to be supplied from renewable sources by 2030.[335]

Scotland's inventions and discoveries are said to have revolutionised human technology and have played a major role in the creation of the modern world. Such inventions – the television, the telephone, refrigerators, the MRI scanner, flushing toilets and the steam engine – are said to have been possible by Scotland's universities and parish schools, together with the commitment Scots had to education during the Scottish Enlightenment.[336] Alexander Fleming is responsible for the discovery of the world's first broadly effective antibiotic substance, which he named penicillin, earning him a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945.[337][338][339] Modern Scottish inventions – the Falkirk Wheel and the Glasgow Tower – hold world records for being the only rotating boat lift and the tallest fully rotating freestanding structure in the world respectively.[340][341]

Scotland's space industry is a world leader in sustainable space technology,[342][343] and, according to the UK Space Agency, there are 173 space companies currently operating in Scotland as of May 2021.[344] These include spacecraft manufacturers, launch providers, downstream data analyzers, and research organisations.[345] The space industry in Scotland is projected to generate £2billion in income for Scotland's space cluster by 2030.[342] Scottish space industry jobs represent almost 1 in 5 of all UK space industry employment.[346] In addition to its space industry, Scotland is home to two planned spaceports – Sutherland spaceport and SaxaVord Spaceport – with launch vehicles such as the Orbex Prime from Scottish–based aerospace company Orbex expected to be launched from Sutherland.[347]

Culture and society

Scottish music

Scottish music is a significant aspect of the nation's culture, with both traditional and modern influences. A famous traditional Scottish instrument is the Great Highland bagpipe, a woodwind reed instrument consisting of three drones and a melody pipe (called the chanter), which are fed continuously by a reservoir of air in a bag. The popularity of pipe bands—primarily featuring bagpipes, various types of snares and drums, and showcasing Scottish traditional dress and music—has spread throughout the world. Bagpipes are featured in holiday celebrations, parades, funerals, weddings, and other events internationally. Many military regiments have a pipe band of their own. In addition to the Great Highland pipes, several smaller, somewhat quieter bellows-blown varieties of bagpipe are played in Scotland, including the smallpipes and the Border pipes.

Scottish popular music has gained an international following, with artists such as Lewis Capaldi, Amy Macdonald, KT Tunstall, Nina Nesbitt, Chvrches, Gerry Cinnamon and Paolo Nutini gaining international success. DJ Calvin Harris was one of the most streamed artists on Spotify in 2023.[348][349] Musical talent in Scotland is recognised via the Scottish Music Awards, Scottish Album of the Year Award, the Scots Trad Music Awards and the BBC Radio Scotland Young Traditional Musician award.

Literature and media