| 2002 Malagasy political crisis (Krizy politika Malagasy 2002) | |

|---|---|

| Date | January 8, 2002 – July 5, 2002 |

| Location | |

| Caused by |

|

| Goals |

|

| Methods | Demonstrations, Riots, General strikes |

| Resulted in |

|

The 2002 Malagasy Political Crisis (Malagasy: Krizy Politika Malagasy 2002) covers the period of mass protests and violent conflict following a dispute over the results of the 2001 Malagasy presidential election. It took place in Madagascar between January-July 2002 and ended with the swearing-in of President Marc Ravalomanana and flight of former president Didier Ratsiraka.

Main Candidates

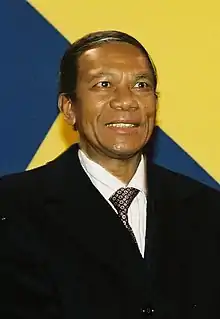

Didier Ratsiraka

Didier Ratsiraka announced his candidacy for president on 26 June, 2001.[1] A formal naval officer, Ratsiraka first came to power in 1975 and ruled Madagascar as president from 1975 to 1992 before losing to Albert Zafy in the 1992-93 Malagasy presidential election. He returned to office after defeating Zafy in the 1996 Malagasy presidential elections, and was the incumbent candidate at the time of the 2001 election. When Ratsiraka announced his presidency, there were no serious challengers and he was widely expected to win another term.[1]

Marc Ravalomanana

Business tycoon Marc Ravalomanana was a political newcomer at the time of the 2001 election. Owner of Tiko, the country's dominant dairy products provider, he had served as mayor of Madagascar's capital Antananarivo since 1999 but had not held national office before the 2001 elections.[1] However, by October 2001 he led Ratsiraka in the polls, thanks in part to his reputation as a successful businessman and to his use of Tiko distribution networks to subtly push campaign slogans.[1][2] In December, Norbert Ratsirahonana, the presidential candidate of the AVI, had withdrawn from the race and endorsed Ravalomanana, which provided bases of support for Ravalomanana outside of his core territories in the capital.[1]

Ravalomanana was also a member of Madagascar's merina ethnic group, which occupies the highlands on the interior of the country. While many merina candidates in preceding elections had been disadvantaged by their ethnic origin, Ravalomanana was not, nor did the post-election violence become organized upon explicitly ethnic lines.[2]

December 2001 Election

Changes to Electoral Process

On 3 September, 2001, Ratsiraka used his presidential authority to enact several changes to the election process. First, he decreed that individuals had to register their candidacy for president by 27 October of that year and simultaneously raised the registration fee, which had the effect of locking out smaller parties and independent candidates that couldn't raise the additional funds within the short timeframe. He also restricted the period for campaigning from 25 November to 15 December and blocked news agencies not aligned with the incumbent government from covering the election. Finally, he prohibited campaign slogans or promotional materials such as posters from being displayed on public buildings or commercial products such as those sold by Ravalomanana's Tiko brand.[2]

Balloting

Ballots for the presidential election were cast on 16 December 2001. The first districts to report were the capital and major metropolitan areas. Ravalomanana took nearly 80% in Antananarivo and a majority in the other urban areas.[1] While there were few irregularities reported with the actual casting of the ballots, the counting of the votes became a source of major controversy. Under Article 47 of Madagascar's constitution, if a candidate is unable to secure an absolute majority in the first round of voting the election proceeds to a runoff between the two candidates with the most votes.[3] Ravalomanana and Ratsiraka were the clear frontrunners, but whether Ravalomanana had secured the necessary majority to avoid a runoff election was heavily disputed.[1]

For the first time in Madagascar's history, non-governmental services were able to conduct their own vote counts.[4] Besides the National Electoral Council (CNE) of the Ministry of the Interior, two other groups provided counts for the 2001 elections: The Committee to Elect Marc Ravalomanana (KMMR), and the Consortium of Election Observers (CNOE), a non-partisan, non-governmental group.[2] However, under pressure from Ratsiraka the CNE had halted the parallel count process with only two thirds of the ballots counted.[2] In the end, the three groups reported widely different counts (see table below). Ravalomanana's camp was able to dispute the results in part because of a network of helicopters and all-terrain vehicles that retrieved copies of the results from remote polling stations and fed them into a central computer system.[4] Because his own figures differed so widely from the government's official tally, Ravalomanana pressed the High Constitutional Court (HCC), the sole body empowered to certify election results, to release the tallies from the individual polling stations to the public.[2][5]

Buoyed by initial results and KMMR counts, Ravalomanana supporters began to celebrate in the capital, and by 4 January 2002 tens of thousands of individuals were taking to the streets to demand that their candidate be recognized as the winner.[1]

| Vote Share (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Election Service | Ravalomanana | Ratsiraka |

| CNE | 46.6 | 40.4 |

| KMMR | 52.2 | 35.7 |

| CNOE | 50.5 | 37.7 |

Election Aftermath

Standoff over Results

In the midst of the growing tension over the election results, Ratsiraka continued to insist that he would abide by whatever decision the High Constitutional court handed down.[2] Pro-Ravalomanana demonstrators became embroiled in violent interactions with the police, and on 7 January 2002 at least 20 people were injured and a child was reportedly killed by police tear gas.[6][7] Crowds of at least 100,000 people were reported.[5]

On 16 January 2002, the HCC ordered that the CNE undertake a closed-door recount of the votes without oversight from candidate representatives or the CNOE.[2] Ravalomanana immediately objected, arguing that the CNE was biased in favor of Ratsiraka, but the recount went ahead anyways. The new CNE total gave Ravalomanana 46.11% of the vote to Ratsiraka's 40.89%.[2] On 25 January 2002 the HCC certified this recount and ruled that a runoff would take place between Ratsiraka and Ravalomanana on 24 February 2002.[1]

The following day Ravalomanana called for a general strike in the capital to protest this ruling, which then began the following Monday, 28 January 2002.[2] This strike involved between 500,000-1,000,000 people and shut down banks, businesses, and international flights from the capital.[2][8] The United Nations Security Council took note of the situation and issued and appeal for both sides to respect the rule of law and engage in a constitutionally-sound election process.[1] Amara Essy, Secretary General to the Organization of African Unity (OAU), made a similar appeal.[1]

On 4 February 2002, Ravalomanana reiterated his unwillingness to participate in a runoff, at which point most of the capital's populace had become engaged in the strike.[1] The World Bank and the IMF estimated that the strike was costing Madagascar's economy between $8 and $14 million a day.[9][10]

By 7 February 2002, Ratsiraka's supporters had begun to blockade the capital by constructing barricades on the main routes to the country's largest port city of Toamasina.[1] This blockade would continue for some months, until almost the end of the crisis.[11]

Ravalomanana Declares Himself President

On 20 February 2002 Ravalomanana announced his intention to declare himself president before a crowd of roughly half a million people, contending that all legal options available to him had been exhausted.[1] He formally declared himself president on 22 February 2002 before a large crowd of supporters, clergy, and judges.[1] In response, Ratsiraka declared a state of emergency in the capital and instituted martial law, placing General Léon-Claude Raveloarison in charge.[2] However, this did little to impede the formation of Ravalomanana's rival government, with Ravalomanana filling out his cabinet appointments by 2 March 2002, with Jaques Sylla, a former foreign minister, as prime minister.[12] While General Raveloarison had ordered his soldiers to defend ministerial buildings and block Ravalomanana's appointees from entering, large crowds accompanying the ministers induced the soldiers on the ground to step aside and Ravalomanana's appointees entered their offices without major incident.[8]

Ratsiraka fled to Toamasina, and on 5 March, 2002, five out of six provincial governors signed an agreement to maintain the blockade of the landlocked Antananarivo, depriving the city of oil and food imports, and designate Toamasina as the country's new capital.[1][2] Ratsiraka also initiated a campaign of violence and intimidation against Ravalomanana's supporters in the coastal regions, and on 14 March 2002 several pro-Ravalomanana merina were killed in Toamasina by security forces.[2]

The supply situation in Antananarivo worsened in early April when paratroopers aligned with Ratsiraka blew up bridges to sever the main three roads into Antananarivo, prompting Ravalomanana to declare the country to be in "a state of war" on 4 April 2002.[11]

Dakar Summits

Ravalomanana and Ratsiraka finally met in person in Dakar, Senegal on 18 April 2002 to sign the Dakar Agreement.[1] This document called for a recount of the first-round votes and a run-off election between the two most popular candidates (not necessarily Ravalomanana and Ratsiraka) in the event a candidate failed to achieve a majority. A transitional government would be appointed by a 'High Transition Council' to oversee the country in the interim period if a runoff was deemed necessary. Moreover, the document called for the blockade of the capital to be lifted and the associated barricades destroyed.[1]

However, the promises made by this document fell through almost immediately as the provincial governors refused to lift the barricades and Ravalomanana refused to relinquish his claim to the presidency.[1] Ratsiraka also made clear his opposition to a recount when he returned to Madagascar on 28 April 2002.[1]

On 29 April 2002, the HCC announced that Ravalomanana had won the first round of voting with 51.46 percent of the vote to Ratsiraka's 35.9 percent.[1] Despite protests from Ratsiraka's camp and the OAU, Ravalomanana was sworn in again on 4 May 2002 with diplomatic representatives from France, the United States, and other select countries in attendance.[1] On 10 May 2002 Norway became the first country to formally recognize Ravalomanana's government.[1]

On 7 June 2002, Ravalomanana appointees formally assumed control of the armed forces and he ordered them to begin preparations to end the blockade of Antananarivo. With both sides gearing up for armed conflict, Ravalomanana and Ratsiraka met again in Dakar on 8 June 2002.[1] However, no agreement was reached as a result of this summit and both men soon returned to Madagascar.[1]

Ravalomanana Secures Power

On 13 June 2002 Ratsiraka and his immediate family flew to Paris, France with the stated purpose of spending several days there before negotiations resumed.[13] Despite his protests that he would soon return to the country, Ratsiraka's trip played havoc with his supporters' morale, and Ravalomanana's troops were able to lift several key barricades, once again opening the capital to vital supplies.[1][14] Ratsiraka returned to Madagascar on 23 June 2002, but the tide was rapidly turning against him.[15] The United States recognized Ravalomanana's government on 26 June 2002 and gave him control of Madagascar's currency assets held by the Federal Reserve.[16] On 3 July, 2002, France followed suit, and Ratsiraka fled Madagascar for the Seychelles on 5 July 2002.[17] [18] On 7 July 2002 Ravalomanana's forces entered Toamasina without resistance, signaling an end to the immediate crisis.[1]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 Cornwell, Richard (1 April 2003). "Madagascar: Stumbling at the First Hurdle?". Institute for Security Studies. ISS Paper 68: 1–16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Marcus, Richard (August 2004). "Political Change in Madagascar: Populist democracy or neopatrimonialism by another name?". Institute for Security Studies. ISS Paper 89: 5.

- ↑ "Madagascar: Constitution of August 19, 1992 (1998 Version)". Retrieved 2022-05-10.

- 1 2 Randrianja, Solofo (2003). "'Be Not Afraid, Only Believe': Madagascar 2002". African Affairs. 102 (407): 309–329. doi:10.1093/afraf/adg006. ISSN 0001-9909. JSTOR 3518681.

- 1 2 "Madagascar protests halted". 2002-01-11. Retrieved 2022-03-31.

- ↑ "'Child killed' in Madagascar protests". 2002-01-07. Retrieved 2022-03-31.

- ↑ "More Madagascar protests". 2002-01-08. Retrieved 2022-04-28.

- 1 2 "Madagascar general strike in support of Marc Ravolomanana, 2002 | Global Nonviolent Action Database". nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu. Retrieved 2022-03-31.

- ↑ Herbert, Ross (1 January 2002). "Madagascar avoidable disaster, test case for African diplomacy". South African Institute of International Affairs. Country Report No. 10: 1–41 – via Africa Portal.

- ↑ "Thousands Protest Against Madagascar Election Results - 2002-02-06". VOA. Retrieved 2022-04-28.

- 1 2 "Madagascar on the brink of civil war". the Guardian. 2002-04-05. Retrieved 2022-03-31.

- ↑ "World Briefing | Africa: Madagascar: 'President' Appoints 'Cabinet'". The New York Times. Reuters. 2002-03-02. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-03-31.

- ↑ "Embattled Ratsiraka arrives in France". 2002-06-14. Retrieved 2022-03-31.

- ↑ "Key Madagascar blockade lifted". 2002-06-13. Retrieved 2022-03-31.

- ↑ "Madagascar rival leader returns". 2002-06-23. Retrieved 2022-04-01.

- ↑ "U.S. Declares a Winner in Disputed Election in Madagascar". The New York Times. Reuters. 2002-06-27. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-04-01.

- ↑ "France backs Ravalomanana". 2002-07-03. Retrieved 2022-04-01.

- ↑ "Madagascar's former leader quits". 2002-07-05. Retrieved 2022-04-01.