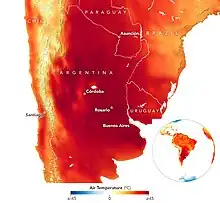

Temperatures in the Southern Cone on 11 January 2022 | |

| Type | Heat wave |

|---|---|

| Areas |

|

| Start date | 10 January 2022 |

| End date | 26 January 2022 |

| Losses | |

| Deaths | 3 |

In mid-January 2022, the Southern Cone had a severe heat wave, which made the region for a while the hottest place on earth, with temperatures exceeding those of the Middle East.[1][2] This extreme weather event was associated with the Atlantic anticyclone,[3] a particularly intense La Niña phenomenon in the Pacific Ocean, and the regional effects of climate change.[4][5]

Several cities had high temperatures over 40 °C (104 °F), setting records for hot days.[6] In addition, thousands of hectares were destroyed by wildfires across the region.[7][8]

By country

Argentina

On January 10, the temperatures were "particularly anomalous" in the south of the Pampas region and the north of Patagonia.[9] According to the Servicio Meteorológico Nacional (SMN), that day maximum temperature records were broken in Tres Arroyos 40.7 °C (105.3 °F) and Coronel Pringles 39.6 °C (103.3 °F), along with other records that ranged between 40 °C (104 °F) and 43 °C (109 °F) in the region. However, a few days later those same marks were surpassed, with 41.8 °C (107.2 °F) in Tres Arroyos and 40.1 °C (104.2 °F) in Coronel Pringles.[10]

On January 11, Buenos Aires reached 41.1 °C (106.0 °F), which was the second maximum temperature at the moment since there are systematic records.[11] That day almost 45.0 °C (113.0 °F) were registered in San Juan, a few tenths of the monthly record for January.[12] On January 12 the city saw 3 heat-related deaths.[13] On January 14, Buenos Aires reached 41.5 °C (106.7 °F), which became the second highest temperature recorded, surpassing that recorded three days earlier.[14]

During the wave, new electric energy consumption records were set at the national level, above 28,000 MW.[15] On January 11, a massive blackout affected 700,000 users in the north of Buenos Aires and Greater Buenos Aires.[16] To avoid blackouts, the Argentine government asked the industrial sector to reduce energy demand between January 13 and 14, with the aim of being able to provide energy to the home network.[17] In addition, it decreed teleworking for two days for public employees and urged provincial governments to take similar measures.[18] During the most intense week of the heat wave, Argentina imported energy from Brazil and Uruguay.[19]

In the midst of the heat wave, and after important fires registered in the previous weeks, especially in Patagonia, the national government declared a fire emergency throughout the country for one year.[20] Fires were recorded in the grasslands and wooded area near Canning and Tristán Suárez, in Ezeiza, which affected some 130 hectares.[21] In Corrientes, a series of wildfires took place, which consumed around 800,000 hectares, which is equivalent to approximately ten percent of the province.[22]

Uruguay

Initially, the Uruguayan Institute of Meteorology (INUMET) issued an alert for the heat wave in the north, center and west of the country, but on January 13 it was extended to the entire country.[23] That day, the maximum temperature of 42.5 °C (108.5 °F) was reached in the northern city of Salto, being the hottest January day since 1961.[24][25] On January 14, Florida reached 44 °C (111 °F), the highest temperature ever recorded in the country, matching a 1943 record.[26] 14 of the 19 departments of the country reached a temperature above 40 °C (104 °F) during the wave.[27]

The heat wave affected the generation of wind power due to the lack of wind, which resulted in 50% of the electrical energy having to be generated with the thermal power stations of the National Administration of Power Plants and Electrical Transmissions (UTE).[28] On January 14, a blackout affected around 25,000 electricity network users in the Canelones, Montevideo and Treinta y Tres departments.[29] On that day the country's energy consumption record was broken, reaching 2,139 MW.[30]

After four days of heat wave, the National Directorate of Firefighters reported more than 100 active fires in different parts of the country, such as Paysandú and Rio Negro.[31][32][33] This weather event intensified the drought, which had triggered a declaration of "agricultural emergency" in December 2021.[34][35] In addition, it caused the death of 400,000 chickens, for an estimated value of 1.5 million dollars,[36] due to this, the Ministry of Livestock, Agriculture and Fisheries declared the "poultry emergency".[37]

See also

References

- ↑ "Southern Hemisphere Scorchers". earthobservatory.nasa.gov. 14 January 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ "América comenzó el 2022 con temperaturas récord y en el sur se espera "la madre de todas las olas de calor"". www.ellitoral.com. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ↑ "Ola de calor asociada a un bloqueo atmosférico por el anticiclón del Atlántico". Nuestroclima (in Spanish). 11 January 2022. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ↑ "La fuerte ola de calor en Sudamérica que pone en alerta a varios países de la región" (in Spanish). BBC News Mundo. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ↑ ElPais (11 January 2022). "Olas de calor: Uruguay en una zona muy caliente". Diario EL PAIS Uruguay (in Spanish). Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ↑ "'Another hellish day': South America sizzles in record summer temperatures". The Guardian. Buenos Aires. Reuters. 14 January 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ "Buenos Aires hits 106 degrees amid severe South American heat wave". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ "Una ola de calor extremo afecta desde la Patagonia al norte de Argentina". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 10 January 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ "Una ola de calor extremo afecta desde la Patagonia hasta el norte de Argentina". www.efe.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ "La ola de calor rompe récords y entra en su etapa más extrema". El Orden de Pringles (in Spanish). Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ TÉLAM. "CABA registró 41.1º, la segunda temperatura más alta desde 1906". www.telam.com.ar (in Spanish). Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ "San Juan lideró el ranking mundial de ciudades más calurosas". www.eldiariodecarlospaz.com.ar (in Spanish). Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ "Los problemas cardíacos y el golpe de calor, el coctel mortal de tres sanjuaninos fallecidos". Tiempo de San Juan (in Spanish). 14 January 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ "La temperatura en CABA llegó a los 41.5° y fue el segundo día más caluroso desde 1906". Todo Noticias (in Spanish). 15 January 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ "BNamericas - Argentina registra pico de demanda eléctrica..." BNamericas.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ "Ola de calor: la demanda eléctrica marcó un nuevo récord histórico y hay miles de usuarios sin luz". Todo Noticias (in Spanish). 13 January 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ Bonelli, Matías (13 January 2022). "Ola de calor: industrias reducen consumo eléctrico y temen que se transforme "en algo habitual"". www.cronista.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ "Para ahorrar energía, el Gobierno manda a los empleados públicos a trabajar desde sus casas". LA NACION (in Spanish). 13 January 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ "Onda de calor na América do Sul pode elevar temperaturas a quase 50 graus". BBC News Brasil (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ "El Gobierno declara la emergencia ígnea en medio de la ola de calor y los incendios en la Patagonia". LA NACION (in Spanish). 12 January 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ "Extinguieron los cinco focos de incendio en Ezeiza y fueron afectadas 130 hectáreas por el fuego". www.ambito.com. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ TÉLAM. "Corrientes: el calor extremo y las sequías generaron nuevos focos de incendios". www.telam.com.ar (in Spanish). Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ Observador, El. "Inumet extendió la alerta por ola de calor a todo el país". El Observador. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ Observador, El. "Salto alcanzó los 42,5°C y rompió el récord histórico de temperatura en enero en Uruguay". El Observador. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ "Temperatures easing in South America heatwave". BBC News. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ "Florida registró 44°C este viernes igualando el récord absoluto de Uruguay registrado en enero de 1943". 970 Universal (in Spanish). 14 January 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ diaria, la (14 January 2022). "Ola de calor: Florida registró un récord histórico de temperatura". la diaria (in Spanish). Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ Observador, El. "Ola de calor afecta generación eólica y parque térmico trepa al 50%". El Observador. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ ElPais (14 January 2022). "Cortes de luz afectaron a unos 25.000 clientes de UTE en Montevideo, Canelones y Treinta y Tres". Diario EL PAIS Uruguay (in Spanish). Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ "Uruguay rompió este viernes el pico histórico de consumo de energía". Telenoche (in Spanish). Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ ElPais (15 January 2022). ""Con la lluvia cambió completamente el panorama", dijo el vocero de Bomberos". Diario EL PAIS Uruguay (in Spanish). Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ EFEverde, Redacción (12 January 2022). "Ola de calor en Uruguay enciende las alarmas ante reproducción de incendios". EFEverde (in Spanish). Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ "A seis meses de los incendios forestales de Río Negro y Paysandú, vecinos y productores afectados se proponen prevenir situaciones similares a futuro". la diaria (in Spanish). 29 June 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ "La ola de calor rompe récords de temperaturas y acentúa sequía en Uruguay". SWI swissinfo.ch (in Spanish). 14 January 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ Observador, El. "Cuáles son los departamentos en emergencia agropecuarias y los apoyos del gobierno". El Observador. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ ElPais (17 January 2022). "Por ola de calor murieron cerca de 400.000 gallinas; "Es histórico", dijo productor". Diario EL PAIS Uruguay (in Spanish). Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ diaria, la (18 January 2022). "MGAP declaró emergencia avícola luego de que por la ola de calor murieran al menos 200.000 aves ponedoras de huevo". la diaria (in Spanish). Retrieved 30 July 2022.