| 21 cm Haubitze M1891 | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) A 21 cm Turmhaubitze captured by the 1st/7th Gordon Highlanders, 51st Division at Flesquieres. 24 November, 1917. | |

| Type | Howitzer |

| Place of origin | |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1891-1918 |

| Used by | |

| Wars | World War I |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Krupp |

| Designed | 1891 |

| Manufacturer | Krupp |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | Barrel: 3,520 kg (7,760 lb) Carriage: 5,740 kg (12,650 lb) Complete:9,260 kg (20,410 lb)[1] |

| Barrel length | 2.4 m (7 ft 10 in) L/11.8 |

| Shell | Separate loading charges and projectiles. |

| Shell weight | 93–140 kg (205–309 lb)[1] |

| Caliber | 209.3 mm (8.24 in) |

| Breech | Horizontal sliding-block |

| Recoil | None |

| Carriage | Box trail |

| Elevation | 0 to +44°[2] |

| Muzzle velocity | 300 m/s (980 ft/s) |

| Maximum firing range | 6.9 km (4.3 mi)[3] |

The 21 cm Haubitze M1891 or (21 cm Howitzer Model 1891) in English was a fortress gun built by Krupp that armed the forts of several European countries before World War I. Two countries that bought the M1891 were Belgium and Romania. In Belgian service it was designated Obusier de 21c.A.[4] and in Romanian service it was designated Obuzierul Krupp, calibrul 210 mm, model 1891.[5]

History

During the second half of the 1800s, several military conflicts changed the balance of power in Europe and set off an arms race leading up to World War I. A company that profited from this arms race was the Friedrich Krupp Company of Essen Germany and several European countries were armed with Krupp artillery. Some customers like Belgium, Italy, Romania, and Russia imported and built Krupp designs under license while others like the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria lacking industrial capacity imported Krupp weapons.[6] In addition to Krupp, one of the most profitable companies during this period was the Grüsonwerke of Magdeburg Germany that specialized in casting large components like armored gun turrets. Grüson turrets armed with Krupp guns became a common feature of European fortifications built during the second half of the 1800s and their success led to Krupp purchasing the Grüsonwerke in 1892.[6]

Design

.JPG.webp)

The 21 cm Haubitze M1891 was a short-barreled breech-loading built-up gun of steel construction. The gun had an early form of horizontal sliding-block breech and it fired separate loading charges and projectiles. Grüsonwerke turrets were large diameter low-profile cast turrets that mounted either cannons or machine guns.[6] The muzzle of the gun fit into a socket at the front of the turret and elevation varied between +4° to +35° depending on the type of gun used and 360° of traverse.[5] By mounting the gun in a socket the majority of the gun could be protected by the turret with only a small part of the muzzle exposed. Beneath the turret, there were traverse and elevation mechanisms for the turret and there were tunnels that connected the turrets to the fort and ammunition bunkers.[6]

World War I

Belgium

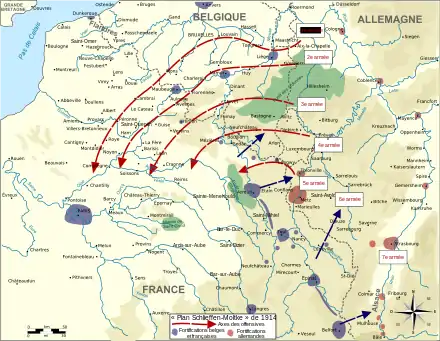

At the outbreak of World War I the Germans put their Schlieffen Plan into motion which featured a wide left hook that was supposed to advance through neutral Belgium into Northern France and envelope Paris from the rear and win the war before the Russians could mobilize their forces to the East.[7] However, their plan was dependent on the Belgians allowing Germany to cross their territory unopposed and Great Britain not honoring its treaty obligations to defend Belgium's neutrality.[8][9]

The Belgian and Romanian fortifications were designed by the Belgian military architect Henri Alexis Brialmont. Brialmont chose 15–21 cm (5.9–8.3 in) guns to arm his forts because he believed that if they could withstand enemy artillery of that size they would be effective. Brialmont assumed that larger siege artillery would be too heavy to transport and too expensive for an attacker to have in sufficient numbers. However, this assumption failed to take into account that forged nickle steel artillery was much lighter than cast bronze or cast iron artillery and although siege artillery was heavy and expensive it was still sufficiently mobile. It also failed to take into account that Germany had heavy mortars like the 25 cm schwerer Minenwerfer that were light, mobile and numerous.[4]

Belgian Forts armed with one Obusier de 21c.A. per Grüson turret included:

18 turrets in the Liège forts.

- 2 turrets at Flémalle, Loncin, Pontisse, Barchon, Fléron, and Boncelles.

- 1 turret at Hollogne, Lantin, Liers, Evegnée, Chaudfontaine, and Embourg.

13 turrets in the Namur forts.

- 2 turrets at St Héribert, Suarlée, Cognelée, and Andoy.

- 1 turret at Malonne, Emines, Marchovelette, Maizeret, and Dave.[4]

To clear the way for their left hook Germany deployed heavy siege guns such as the Škoda 305 mm Mörser M.1911 and the Krupp 420 mm (17 in) Big Bertha to attack the forts blocking Germany's path through Belgium. While the Belgian forts delayed Germany's advance through Belgium they could not stop it and the majority of their forts were besieged and destroyed.[10]

Germany

The majority of military planners before the First World War were wedded to the concept of fighting an offensive war of rapid maneuver which before mechanization meant a focus on cavalry and light horse artillery firing shrapnel shells. Although the majority of combatants had heavy field artillery before the outbreak of the First World War, none had adequate numbers of heavy guns in service, nor had they foreseen the growing importance of heavy artillery once the Western Front stagnated and trench warfare set in.[11]

The theorists hadn't foreseen that trenches, barbed wire, and machine guns had robbed them of the mobility they had been counting on. Since aircraft of the period were not yet capable of carrying large-diameter bombs the burden of delivering heavy firepower fell on the artillery. The combatants scrambled to find anything that could fire a heavy shell and that meant emptying the fortresses and scouring the depots for guns held in reserve. It also meant converting coastal artillery and naval guns to siege guns by either giving them simple field carriages or mounting the larger pieces on rail carriages.[11]

The race to the sea created a front line that stretched from Switzerland to the English Channel required more guns and a combination of production shortfalls and higher than expected artillery losses during the first year of World War I meant Germany faced a shortage of artillery and ammunition. Fortunately, Germany had captured large stocks of enemy artillery and ammunition during the first two years of World War I. However, Germany's dependence on using captured artillery with non-standard ammunition strained Germany's logistics in the long run.[12]

One type of Kriegsbeute or (war booty) in English was the M1891s that were salvaged from wrecked Belgian forts. The gun barrels were placed on a simple box trail carriage made from riveted steel plates and there were two large spoked cast iron wheels at the front. The carriage had a cutout behind the breech to allow 0° to +44° of elevation.[2] Like many of its contemporaries, it did not have a recoil mechanism. There was also no gun shield or traversing mechanism and the gun had to be levered into position to aim. For prolonged use, a spot of ground could be leveled and a wooden firing platform could be laid for the gun. A set of ramps were then placed behind the wheels and when the gun fired the wheels rolled up the ramp and returned to battery by gravity. A drawback of this system was the gun had to be re-aimed each time which lowered the rate of fire. The converted gun was given the designation 21 cm Turmhaubitze M1891 or 21 cm Turret Howitzer M1891 in English and armed German heavy artillery units. Its nearest German equivalent would be the 21 cm Mörser 99 which fired a projectile of roughly the same weight to a similar range but the M1891 was twice as heavy.

Romania

Romania also had forts equipped with Grüson turrets armed with M1891 guns. Before their entry into World War I on the side of the allies Romania had thirty-six M1891 guns. Romania had forts to the South along their border with Bulgaria, to the East along their border with Russia, and a ring of forts surrounding Bucharest.[13] After seeing how Belgium's forts were destroyed by the Germans in 1914 the Romanian Army began removing their guns from their forts and converting them into mobile field artillery.[14][15][16] Before entering World War I thirteen M1891 guns were removed from Romanian fortifications and placed on locally built garrison mounts to serve as heavy field artillery. The guns lacked a recoil mechanism, gun shield or traversing mechanism and the gun had to be levered into position to aim. The simple carriage had an axle at the front that could be fitted with large diameter wheels for transport and removed once in place. A small set of wheels at the front of the carriage were used for aiming the guns.[5]

Surviving guns

Photo Gallery

.jpg.webp) German officers inspect a destroyed Belgian M1891 gun turret.

German officers inspect a destroyed Belgian M1891 gun turret. A Belgian turret at Fort Loncin destroyed by a 42 cm (17 in) projectile from a Big Bertha siege gun.

A Belgian turret at Fort Loncin destroyed by a 42 cm (17 in) projectile from a Big Bertha siege gun. A Belgian M1891 turret at Fort Loncin. An explosion in the ammunition bunker threw the turret into the air and it landed upside down in its own pit largely intact.

A Belgian M1891 turret at Fort Loncin. An explosion in the ammunition bunker threw the turret into the air and it landed upside down in its own pit largely intact. A 21 cm Turmhaubitze captured by the 1st/7th Gordon Highlanders, 51st Division at Flesquieres. 24 November 1917.

A 21 cm Turmhaubitze captured by the 1st/7th Gordon Highlanders, 51st Division at Flesquieres. 24 November 1917. A Romanian M1891 on a garrison mount (right).

A Romanian M1891 on a garrison mount (right).

References

- 1 2 "Romanian fortress guns data". www.bulgarianartillery.it. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

- 1 2 "Das Gerät der schweren Artillerie vor, in und nach dem Weltkrieg". www.digitalniknihovna.cz. Retrieved 2021-04-20.

- ↑ "Ob. 21 c.A. Mod. 1889". www.passioncompassion1418.com. Retrieved 2021-04-20.

- 1 2 3 "Obusier de 21c.A.Krupp (manchonné et fretté)". www.passioncompassion1418.com. Archived from the original on 2021-01-27. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

- 1 2 3 "Romanian Artillery in 1916". www.bulgarianartillery.it. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

- 1 2 3 4 Jäger, Herbert (2001). German artillery of World War One. Marlborough: Crowood Press. pp. 96–104. ISBN 1-86126-403-8. OCLC 50842313.

- ↑ Foley, Robert T. (2007). German strategy and the path to Verdun : Erich von Falkenhayn and the development of attrition, 1870-1916. Cambridge, UK. pp. 77–78. ISBN 978-0-521-84193-1. OCLC 778889553.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "German Request for Free Passage through Belgium, and the Belgian Response, 2–3 August 1914". www.firstworldwar.com. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ↑ World War I — 1914 Opening Campaigns Archived 2015-04-03 at the Wayback Machine Kennedy Hickman.

- ↑ Tuchman, Barbara W. (2012). The guns of August; The proud tower. Margaret MacMillan. New York, NY: Library of America. pp. 191–214. ISBN 978-1-59853-145-9. OCLC 731911132.

- 1 2 Hogg, Ian (2004). Allied artillery of World War One. Ramsbury: Crowood. pp. 129–134 & 218. ISBN 1861267126. OCLC 56655115.

- ↑ Fleischer, Wolfgang (2015). German artillery : 1914-1918. Barnsley. pp. 13–15. ISBN 978-1-4738-2398-3. OCLC 893163385.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "Romanian fortifications". www.bulgarianartillery.it. Retrieved 2021-04-22.

- ↑ Daniel Popa (December 10, 2005). "Forturile Bucureștiului, transformate în ciupercării, depozite și cimitire" [The Forts of Bucharest, Transformed into Mushroom-Growing Facilities, Deposits and Cemeteries]. România Liberă (in Romanian). Retrieved June 26, 2008.

- ↑ Ciprian Plăiașu (September 11, 2012). "'Cetății' Bucureștiului i se refuză recunoașterea istorică" [Bucharest 'Citadel' Denied Historic Recognition]. Adevărul (in Romanian). Retrieved September 11, 2012.

- ↑ Vlad Ignat (December 28, 2012). "Fortificațiile din jurul Capitalei" [The Fortifications around the Capital]. Adevărul (in Romanian). Retrieved December 29, 2012.

- ↑ "210mm FORTIFICATION GUN KRUPP | 3DHISTORY.DE". 3dhistory.de. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

- ↑ "46 German WWI 210mm Howitzer". www.militarymuseums.info. Retrieved 2021-04-21.