| 3 Women | |

|---|---|

.png.webp) Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Robert Altman |

| Written by | Robert Altman |

| Produced by | Robert Altman |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Charles Rosher Jr. |

| Edited by | Dennis Hill |

| Music by | Gerald Busby |

Production company | Lion's Gate Films |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 124 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.7 million[1] |

3 Women is a 1977 American psychological drama film written, produced and directed by Robert Altman and starring Shelley Duvall, Sissy Spacek and Janice Rule. Set in a dusty California desert town, it depicts the increasingly bizarre relationship between a woman (Duvall), her roommate and co-worker (Spacek) and an older pregnant woman (Rule).

The story came directly from a dream Altman had, which he adapted into a treatment, intending to film without a screenplay. 20th Century Fox financed the project on the basis of Altman's past work, and a screenplay was completed before filming.

3 Women premiered at the 1977 Cannes Film Festival and earned positive reviews from critics, who particularly praised the performances of the cast (especially Duvall's). Interpretations of the film are centered around its use of psychoanalysis and discussion of identity. It was not a strong box office success despite Hollywood studio financing and distribution. After its theatrical release, the film was unavailable on home video for almost thirty years, until it was released by The Criterion Collection in 2004.

Plot

Pinky Rose, a timid and awkward young woman, starts working at a health spa for the elderly in a small California desert town. She becomes enamored of Millie Lammoreaux, a relentlessly outgoing and self-absorbed co-worker who talks incessantly. Despite their stark personality differences, Pinky and Millie become roommates at the Purple Sage Apartments, owned by a drinking, womanizing, has-been Hollywood stunt double, Edgar Hart, and his wife Willie, a mysterious pregnant woman who rarely speaks and paints striking and unsettling murals.

Millie takes Pinky along on her visits to Dodge City, a local tavern and shooting range also owned by Willie and Edgar, where Millie continues expounding her petty opinions and interests to her new roommate. Millie's babble alienates most of her co-workers, neighbors, acquaintances, and would-be suitors; Pinky is the only person in Millie's orbit who enjoys her advice about dating, fashion, cuisine and interior decorating gleaned from women's magazines.

Tensions begin to rise between Pinky and Millie over their living situation. After a quarrel with Pinky one night, Millie leaves the apartment and returns with a drunken Edgar. Pinky begs Millie to consider Edgar's pregnant wife and not have sex with him. Millie, angry at what she perceives as Pinky's meddling and sabotaging her social life, yells at her and suggests she move out of the apartment. A distraught Pinky jumps off the apartment balcony into the swimming pool.

Pinky survives the suicide attempt but falls into a coma. Millie, feeling responsible, visits her in the hospital daily. When Pinky still fails to wake up, Millie contacts Pinky's parents in Texas, hoping their presence at the hospital will help her regain consciousness. When Pinky wakes up, she does not recognize her parents and furiously demands that they leave. Once sent home to live with Millie again, Pinky copies Millie's mannerisms and behavior—drinking and smoking, sleeping with Edgar, shooting guns at Dodge City—and demands to be called Mildred, both women's birth name.

Millie becomes increasingly frustrated by Pinky's imitative shift in personality and begins to exhibit Pinky's timid and submissive personality herself. One night after Pinky has a bad dream, she shares a bed with Millie platonically. Edgar, soused again, enters their apartment and makes sexual overtures before casually telling them that Willie is about to give birth. Pinky and Millie drive to Edgar and Willie's house, where Willie is alone and in agonizing labor. Her baby is stillborn, as Pinky fails to summon medical help during the delivery as Millie told her to.

Later, Pinky and Millie are working at Dodge City, having again changed roles: Pinky has reverted to her child-like timidity and refers to Millie as her mother, while Millie has assumed Willie's role in running the tavern—even imitating Willie's make-up and attire. A delivery vendor at the tavern refers to Edgar's death from a "gun accident" when talking to Millie, who offers a pat, hollow reply that suggests the three women are complicit in Edgar's murder.

Cast

- Shelley Duvall as Mildred "Millie" Lammoreaux

- Sissy Spacek as Mildred "Pinky" Rose

- Janice Rule as Willie Hart

- Robert Fortier as Edgar Hart

- Ruth Nelson as Mrs. Rose

- John Cromwell as Mr. Rose

- Sierra Pecheur as Ms. Bunweil

- Craig Richard Nelson as Dr. Maas

- Maysie Hoy as Doris

- Belita Moreno as Alcira

- Leslie Ann Hudson as Polly

- Patricia Ann Hudson as Peggy

- Beverly Ross as Deidre

Production

Development

Director Robert Altman conceived of the idea for 3 Women while his wife was being treated in a hospital, and he was afraid that she would die.[2] During a restless sleep, he had a dream in which he was directing a film starring Shelley Duvall and Sissy Spacek in an identity theft story, against a desert backdrop.[3] He woke up mid-dream, jotted notes on a pad, and went back to sleep, receiving more details.[2]

Upon waking up, he wanted to make the film, although the dream had not provided him with a complete storyline. Altman consulted author Patricia Resnick to develop a treatment, drawing up 50 pages, initially with no intent to write a full screenplay.[3] Ingmar Bergman's 1966 film Persona was also an influence on the film.[4]

Altman secured approval from 20th Century Fox, which supported the project on the basis of the success of his 1970 film MASH.[3] Studio manager Alan Ladd Jr. also found the story idea interesting, and respected the fact that Altman consistently worked within his budget in past films, as this was before Altman's 1980 film version of Popeye considerably exceeded its initially approved budget.[5]

Filming

The film was shot in Palm Springs, including the apartment scenes, and Desert Hot Springs, California.[6][7] Although a screenplay was completed, actresses Duvall and Spacek employed much improvisation, particularly in Duvall's silly ramblings and advice on dating.[3] Altman also credited Duvall with drawing up her character's recipes and diary.[8]

For Willie's paintings, the filmmakers employed artist Bodhi Wind, whose real name was Charles Kuklis.[9] The cinematographer, Charles Rosher Jr., worked with the intense sunlight in the California desert.[10]

During the shooting of one scene, Duvall's skirt got caught in a car door. Assistant director Tommy Thompson called for a cut. However, Altman stated he "loved" the accident, and had Duvall intentionally catch her dress and skirt in the door in several scenes.[11]

Themes and interpretations

Altman has said the film is about "empty vessels in an empty landscape".[12] Writer Frank Caso identified themes of the film as including obsession, schizophrenia and personality disorder, and linked the film to Altman's earlier films That Cold Day in the Park (1969) and Images (1972), declaring them a trilogy. Caso states critics have argued the dreamer in the film is Willie, since she says she had a dream at the end of the film, and Pinky had the "dream within a dream".[13]

Psychiatrist Glen O. Gabbard and Krin Gabbard believed 3 Women could best be understood through psychoanalysis and the study of dreams. In theory, a person dreaming can shift from one character into another within the dream. The three titular characters in the film represent the psyche of one person.[6] Whereas Pinky is the child among the three, Millie is the sexually awakened young woman and the pregnant Willie is the mother figure.[14] The Gabbard siblings interpreted Pinky, post-coma, as transforming into Millie, while Millie became more of a mother figure to her.[15] Altman equated the death of Willie's child to the murder of Edgar, which the three title characters appear to all have participated in.[16] Author David Greven agreed psychoanalysis could be used, but saw the relationship between Millie and Pinky as one of mother and daughter, respectively, with Willie at the end of the film being the "grandmotherly figure" who defends Pinky from Millie's scornful mothering. Greven wrote the film also demonstrated a focus on strong female characters.[17]

The setting is also a key feature in the film, with Joe McElhaney arguing the California landscapes "come to represent something much larger than a 'mere' location".[18] He states it is "a space of death but also one of creation".[19]

Release

The film opened in New York City in April 1977.[20] The film was also screened at the Cannes Film Festival in May 1977, which was where Altman first admitted to Ladd the film was based on his dream.[21]

On home video, the film never had a VHS release, and Altman said the film negative was beginning to deteriorate until it was repaired and remastered.[22] However, The Criterion Collection released the film on DVD in 2004, with a director's commentary.[22] Criterion re-released the film on Blu-ray in 2011.[23]

Reception

Critical reception

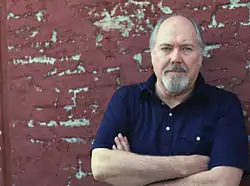

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

The film has an 85% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes, based on 53 reviews,[24] and has received generally positive reviews from critics.[25] Roger Ebert gave the film four stars, calling the first half "a funny, satirical, and sometimes sad study of the community and its people," and adding the film then turns into "masked sexual horror".[26] Ebert added 3 Women to his Great Movies list in 2004, calling it "Robert Altman's 1977 masterpiece" and stating Duvall's expressions are "a study in unease".[4]

Vincent Canby, writing for The New York Times, called 3 Women a "funny, moving" film, and Millie "one of the most memorable characterizations Mr. Altman has ever given us," giving credit to Duvall as well.[20] Molly Haskell, in New York, ranked the film as the second best of the year, describing it as "ambitious, pretentious, gentle, goofy and mesmerizing".[27] Texas Monthly critics Marie Brenner and Jesse Kornbluth stated Altman had a likely desire to be the "American Bergman," calling 3 Women "an attempt at equaling Bergman's Persona".[28]

Brenner and Kornbluth credited Duvall for an "extraordinary performance," but lamented the second-half shedding a documentary style.[29] Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times wrote, "It needed no proving, but on the evidence of his '3 Women,' Robert Altman is identifiable anew as one of the most fluent, imaginative, individual and magical film-makers working here or anywhere else."[30] Gene Siskel gave the film two-and-a-half out of four stars, saying he still didn't understand it after seeing it twice. "The ultimate meaning of 'Three Women' may be known only to writer-director Altman," Siskel wrote. "After all, it was his dream. I didn't find enough threads of sanity to keep me interested in the film's final sequences."[31]

Writing for The New Yorker, Michael Sragow remarked "In the Robert Altman canon, no picture is stranger—and more fascinating—than this 1977 phantasmagoria," adding it is "full of images so rich that they transcend its metaphoric structure," praising Duvall.[32]

Accolades

| Award | Date of ceremony | Category | Recipient(s) | Result | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Academy Film Awards | March 16, 1978 | Best Actress | Shelley Duvall | Nominated | [33] |

| Cannes Film Festival | May 13 – 27, 1977 | Palme d'Or | Robert Altman | Nominated | [34] |

| Best Actress | Shelley Duvall | Won | |||

| Los Angeles Film Critics Association | December 19, 1977 | Best Actress | Won | [35] | |

| National Society of Film Critics Awards | December 19, 1977 | Best Actress | Runner-up | [36] | |

| Best Supporting Actress | Sissy Spacek | Runner-up | |||

| New York Film Critics Circle | January 29, 1978 | Best Actress | Shelley Duvall | Runner-up | [37] |

| Best Supporting Actress | Sissy Spacek | Won | |||

References

- ↑ Kilday, Gregg (September 8, 1976). "A Dream Movie From Altman". Los Angeles Times. p. E10.

- 1 2 Altman 2000, p. 194.

- 1 2 3 4 Sterritt, David (2004). "3 Women: Dream Project". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- 1 2 Ebert, Roger (26 September 2004). "3 Women". Rogerebert.com. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ↑ Armstrong 2011, p. 10.

- 1 2 Gabbard & Gabbard 1999, p. 223.

- ↑ McElhaney 2015, p. 154.

- ↑ Altman, Robert (2004). Robert Altman's 3 Women (DVD). The Criterion Collection.

- ↑ Niemi 2016.

- ↑ McElhaney 2015, p. 151.

- ↑ Zuckoff 2010, pp. 321–322.

- ↑ Mazur 2011, pp. 13.

- ↑ Caso 2015.

- ↑ Gabbard & Gabbard 1999, pp. 223–224.

- ↑ Gabbard & Gabbard 1999, p. 227.

- ↑ Gabbard & Gabbard 1999, p. 230.

- ↑ Greven 2013, p. 236.

- ↑ McElhaney 2015, p. 150.

- ↑ McElhaney 2015, p. 153.

- 1 2 Canby, Vincent (11 April 1977). "Altman's '3 Women' a Moving Film; Shelley Duvall in Memorable Role". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ↑ Zuckoff 2010, p. 320.

- 1 2 Clements, Marcelle (30 May 2004). "Film/DVD; '3 Women' Coming of Age At 27". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ↑ Wilkins, Budd (20 October 2011). "3 Women". Slant Magazine. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ↑ "3 Women (1977)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ↑ Cook 2002, p. 96.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (15 March 1977). "3 Women". Rogerebert.com. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ↑ Haskell, Molly (26 December 1977). "Choice and Prime". New York. p. 82.

- ↑ Brenner, Marie; Kornbluth, Jesse (June 1977). "Altman Stays Serious". Texas Monthly. p. 118.

- ↑ Brenner, Marie; Kornbluth, Jesse (June 1977). "Altman Stays Serious". Texas Monthly. p. 120.

- ↑ Champlin, Charles (April 27, 1977). "Altman Magic in '3 Women'". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 1.

- ↑ Siskel, Gene (June 14, 1977). " 'Three Women': What's the meaning of this, Mr. Altman?". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 7.

- ↑ Sragow, Michael. "3 Women". The New Yorker. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ↑ "Actress in 1978". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ↑ "Festival de Cannes: A Child in the Crowd". festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on 27 September 2012. Retrieved 2009-05-10.

- ↑ "Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards (1977)". IMDb.

- ↑ "'Annie Hall' Picked as Best of '77 By National Film Critics Society". The New York Times. 20 December 1977. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ↑ Maslin, Janet (22 December 1977). "Critics' Circle Picks 'Annie Hall'". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

Bibliography

- Altman, Robert (2000). Robert Altman: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 1578061873.

- Armstrong, Rick (2011). Robert Altman: Critical Essays. McFarland & Company Publishers. ISBN 978-0786486045.

- Caso, Frank (2015). "Strange Interlude". Robert Altman: In the American Grain. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1780235523.

- Cook, David A. (2002). Lost Illusions: American Cinema in the Shadow of Watergate and Vietnam, 1970-1979. University of California Press. ISBN 0520232658.

- Gabbard, Glen O.; Gabbard, Krin (1999). Psychiatry and the Cinema (Second ed.). Washington, D.C. and London: American Psychiatric Press, Inc. ISBN 0880489642.

- Greven, David (2013). Psycho-Sexual: Male Desire in Hitchcock, De Palma, Scorsese, and Friedkin. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0292742024.

- Mazur, Eric Michael (2011). Encyclopedia of Religion and Film. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-31333-072-8.

- McElhaney, Joe (2015). "3 Women: Floating Above the Awful Abyss". In Danks, Adrian (ed.). A Companion to Robert Altman. Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 978-1118338957.

- Niemi, Robert (2016). "3 Women (1977)". The Cinema of Robert Altman: Hollywood Maverick. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231176279.

- Zuckoff, Mitchell (2010). Robert Altman: The Oral Biography. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0307387912.

External links

- 3 Women at IMDb

- 3 Women at AllMovie

- 3 Women at Rotten Tomatoes

- 3 Women at the American Film Institute Catalog

- 3 Women at the TCM Movie Database

- A Dream Team: Patricia Resnick on 3 Women – an essay by Sam Wasson at The Criterion Collection