| 44th Missouri Infantry Regiment | |

|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) 35-star United States flag (1863) | |

| Active | 22 Aug. 1864 – 15 Aug. 1865 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | Union Army |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | Regiment |

| Engagements |

|

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Robert C. Bradshaw |

44th Missouri Infantry Regiment was a infantry unit from Missouri that served in the Union Army during the latter part of the American Civil War. The regiment was organized in August and September 1864 to serve for 12 months, with the tenth company only serving six months. Beginning in November, the unit fought in the Franklin–Nashville Campaign. At the Franklin on 30 November 1864, the regiment suddenly found itself in the center of an extremely bloody fight. In March and April 1865, the regiment was part of the expedition that seized Mobile, Alabama. The soldiers were mustered out of Federal service in mid-August 1865.

Formation

The 44th Missouri Infantry Regiment organized at St. Joseph, Missouri between 22 August to 7 September 1864. Companies A through I were to serve for one year, while Company K was only to serve for six months.[1] The field officers were Colonel Robert C. Bradshaw, Lieutenant Colonel Andrew J. Barr, and Major Roger A. De Bolt. Bradshaw's commission ran from 4 August 1864 and he was from St. Joseph. Barr's commission was dated 28 September and he was from Richmond, Missouri. De Bolt's commission ran from 3 November and he was from Trenton, Missouri. Each infantry company had one captain, one first lieutenant, and one second lieutenant. The adjutant was Hanson H. Ware, the quartermaster was J. M. Hoskinson, and the surgeon was Henry Schoenich.[2] The chaplain was Thomas B. Bratton.[1]

Colonel Bradshaw joined the 25th Missouri Infantry Regiment in June 1861 as a private and rose to the rank of captain before resigning in January 1864. He joined the 87th Enrolled Missouri Militia Regiment on 13 July 1864 with the rank of major and two days later became lieutenant colonel. At the conclusion of hostilities, Bradshaw earned appointment as brevet brigadier general for war service.[3] Lieutenant Colonel Barr was discharged on 15 May 1865 and Major De Bolt was discharged on 12 July 1865.[1]

| Company | Captain | To Rank From |

|---|---|---|

| A | John C. Reid | 10 September 1864 |

| B | William Drumhiller | 3 November 1864 |

| C | Frank G. Hopkins | 3 September 1864 |

| D | William B. Rogers | 10 September 1864 |

| E | Ephraim L. Webb | 4 September 1864 |

| F | Isaac M. Henry | 27 September 1864 |

| G | Anthony L. Bowen | 7 September 1864 |

| H | William D. Fortune | 6 September 1864 |

| I | Anthony Muck | 9 September 1864 |

| K | Nathan A. Winters | 10 September 1864 |

History

Spring Hill and Franklin

After its formation, the 44th Missouri Infantry was attached to the District of Rolla, Department of Missouri through November 1864.[4] The regiment moved to Rolla, Missouri by railroad on 14–18 September and remained there until 6 November. Due to sickness and various duties, the regiment did not have enough time for drill. When the soldiers were notified that they were to serve outside of Missouri, many soldiers expressed dissatisfaction.[5] The unit took part in an expedition from Rolla to Licking, Missouri from 5–9 November. The 44th Missouri Infantry moved to Paducah, Kentucky on 12–16 November. The regiment was briefly attached to Paducah, Department of the Ohio. From Paducah, the unit traveled to Nashville, Tennessee on 24–27 November and to Columbia, Tennessee on 28 November. At this time, the regiment transferred to the XXIII Corps but was not assigned to a brigade.[4] The IV Corps and XXIII Corps were led by John M. Schofield.[6]

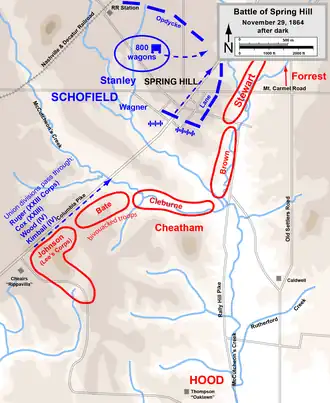

On 22 November 1864, Schofield learned that John Bell Hood's Confederate Army of Tennessee was advancing north into Tennessee from Florence, Alabama. The Union commander started a hasty withdrawal of his 22,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry from Pulaski, Tennessee to Columbia.[7] On 24 November, Schofield's army reached Columbia and took up defensive positions.[8] On the morning of 29 November, Hood's army established a foothold on the north bank of the Duck River east of Columbia and began crossing with the goal of cutting off Schofield's army from Nashville.[9] In the Battle of Spring Hill, Hood's maneuver brought 19,000 Confederate troops against 6,000 Federals in Schofield's rear. Believing he would capture the Union troops in the morning, Hood went to bed, not realizing his plan would miscarry.[10] When Schofield became aware of the situation and retreated, his army made a desperate night march past the Confederate army.[11] The 44th Missouri came into action for the first time at Spring Hill, holding a blocking position while most of the army marched past. The regiment formed part of the rearguard until 10:00 am the following day.[12] During the retreat to Franklin, a Union veteran noticed that the new recruits discarded their unneeded possessions along the roadside, "Pocket bibles, book marks, pots of jam, whiskbrooms, euchre decks, poker chips, love letters, night shirts".[13]

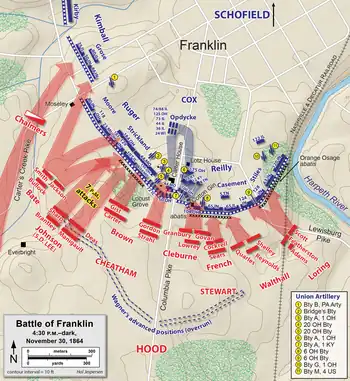

The 44th Missouri fought in the Battle of Franklin on 30 November 1864.[4] Angry at the missed opportunity the previous day and over the objections of his generals, Hood ordered a massed assault.[14] Meanwhile, the Federal troops improved an old line of entrenchments that covered the southern side of Franklin. Soon the earthworks were 5 ft (1.5 m) high and 4 ft (1.2 m) thick, with a ditch. Because there was a gap at the Columbia Pike, the Union soldiers built a second entrenchment about 70 yd (64 m) behind the first and only 100 yd (91 m) long.[15] The 44th Missouri Infantry was posted behind this second breastwork near the Columbia Pike and the Carter House.[16] Out in front of the Union fortifications were two brigades from George D. Wagner's division. Despite pleas from his brigadiers to pull back, Wagner misconstrued his instructions and insisted that his two brigades hold their ground "at the point of bayonet".[17]

Hood's 20,000 charging infantry hit Wagner's two brigades, routing them and sending the soldiers fleeing back toward the main Federal lines. The stampeding troops blocked the fire of the Union soldiers in the trenches and the pursuing Confederates quickly seized a 200 yd (183 m) section of fortifications. Three Federal regiments in the front line and parts of two others from the second line joined the rout of Wagner's two brigades. Emerson Opdycke commanded Wagner's third brigade which was positioned in reserve 200 yd (183 m) north of the Carter House. When the mob of fleeing Union soldiers swept past them, Opdycke's regiments spontaneously charged and recaptured the second line. Once there, Opdycke's men were joined by rallied soldiers of the routed regiments so that they were formed four or five ranks deep. Men in the rear ranks loaded and passed their weapons forward; the front rank fired and passed them back.[18][note 1] When more Confederate brigades appeared, they tried to rush the second line but were stopped with heavy losses. A Union soldier in the second line saw a field officer of the 44th Missouri jump on top of the breastworks and call for a counterattack before being immediately shot down.[19] This officer was probably Colonel Bradshaw who was hit by seven bullets but survived. The counterattack failed with 35 privates killed and the survivors retreating to the second line, unable to retrieve the wounded. At midnight, the regiment silently left the trenches and retreated to Nashville.[20]

The defeat at Franklin cost Hood's army 6,252 casualties, including about 1,750 killed. Union casualties numbered 2,326, mostly due to Wagner's blunder.[21] Second Lieutenants Benjamin Kirgan of F Company and Samuel Warner of K Company were killed in action at Franklin. First Lieutenant James Dunlap of E Company was mortally wounded and died 11 December 1864.[2][1] One source listed the 44th Missouri's losses as 67 killed, 43 wounded, and 39 captured, for a total of 149 casualties at Franklin.[22] The Official Army Register of the Volunteer Force of the United States Army listed the regiment's losses at Franklin as eight killed, 23 wounded, and 111 missing.[1]

Nashville and Mobile

The 44th Missouri Infantry transferred to 2nd Brigade, 3rd Division, (Detachment) Army of the Tennessee, Army of the Cumberland from December 1864 to February 1865.[4] At the Battle of Nashville on 15–16 December 1864, the regiment was led by Lieutenant Colonel Barr. The 2nd Brigade was commanded by Colonel Leander Blanden, the 3rd Division by Colonel Jonathan Baker Moore, and the (Detachment) Army of the Tennessee by Andrew Jackson Smith.[23] On 16 December, Schofield asked for reinforcements for his XXIII Corps so Smith sent the 3rd Division to his support.[24] That afternoon, Smith's 1st and 2nd Divisions assaulted and broke Hood's lines, capturing 4,273 Confederates and 24 guns.[25] Only one of the XXIII Corps brigades came into action that day.[26]

The 44th Missouri Infantry participated in the pursuit of Hood's army to Columbia and Pulaski on 17–28 December 1864. By the time the regiment reached Pulaski, two-thirds of the soldiers were barefooted. Nevertheless, the troops were ordered to march 60 mi (97 km) through ice and snow to Clifton, Tennessee where they arrived on 2 January 1865 with their feet in bad condition. The unit was transported on the steamer Clara Poe on 9–11 January to Eastport, Mississippi where it camped until 6 February. The soldiers participated in a short expedition to Corinth, Mississippi. From Eastport, the regiment moved via river transport to New Orleans where it arrived on 21 February.[27] Company K was mustered out on 22 March 1865.[1]

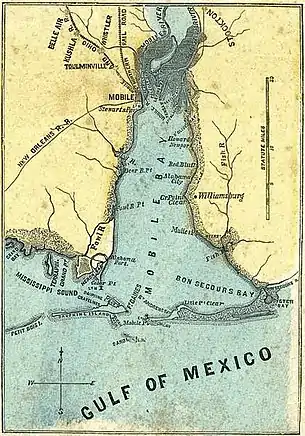

The 44th Missouri participated in the campaign against Mobile, Alabama and its defenses from 11 March–12 April 1865.[4] The regiment departed by ship from New Orleans on 11 March and reached Dauphin Island on 14 February. After three day, the unit boated to Cedar Point where it stayed until 22 February. The regiment then took ship to Fish River where it landed on 23 February.[27] The unit took part in the siege and Battle of Spanish Fort on 26 March–8 April 1865. From February to August 1865, the 44th Missouri belonged to the 1st Brigade, 3rd Division, XVI Corps, Military Division West Mississippi.[4] In the campaign, the 44th Missouri was led by Captain Hoskins. The 1st Brigade was led by Colonel Moore, the 3rd Division was commanded by Brigadier General Eugene Asa Carr, and the XVI Corps by A. J. Smith. The other units in Moore's brigade were the 33rd Wisconsin, 72nd Illinois, and 95th Illinois Infantry Regiments.[28]

After the fall of Mobile, the 44th Missouri marched to Montgomery, Alabama where it arrived on 25 April. From there it traveled to Tuskegee, Alabama which it occupied until July 19. It moved to Vicksburg, Mississippi which it reached on 28 July. After two days the regiment embarked for St Louis where it arrived on 4 August. The regiment was mustered out of service on 15 August 1865, having traveled 5,703 mi (9,178 km) of which 747 mi (1,202 km) were on foot.[27]

Casualties

The regiment lost four officers and 61 enlisted men killed or mortally wounded in action. Five officers and 168 enlisted men died by disease, for a total of 238 deaths.[4][note 2]

| Action | Officers Killed | Enlisted Killed | Officers Wounded | Enlisted Wounded | Officers Missing | Enlisted Missing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring Hill | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Franklin | 2 | 6 | 3 | 20 | 0 | 111 |

| Nashville | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Spanish Fort | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

See also

Notes

- Footnotes

- ↑ According to Sword's map (page 200), the two second line units were the 44th Missouri and the 183rd Ohio Infantry. Joining Opdycke's brigade in the counterattack were one Tennessee and two Kentucky regiments.

- ↑ The 61 enlisted men listed as killed or mortally wounded by Dyer cannot be reconciled with the eight killed listed in the Official Army Register.

- Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Official Army Register 1867, p. 133.

- 1 2 3 Annual Report 1866, pp. 274–275.

- ↑ Boatner 1959, p. 78.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Dyer 1908, p. 1337.

- ↑ Annual Report 1866, p. 275.

- ↑ Sword 1992, p. 448.

- ↑ Sword 1992, pp. 82–83.

- ↑ Sword 1992, pp. 93–94.

- ↑ Sword 1992, pp. 97–98.

- ↑ Sword 1992, pp. 130–139.

- ↑ Sword 1992, pp. 141–143.

- ↑ Annual Report 1866, p. 276.

- ↑ Sword 1992, p. 162.

- ↑ Sword 1992, p. 179.

- ↑ Sword 1992, pp. 163–164.

- ↑ Sword 1992, p. 200.

- ↑ Sword 1992, pp. 189–190.

- ↑ Sword 1992, pp. 199–206.

- ↑ Sword 1992, pp. 207–211.

- ↑ Annual Report 1866, pp. 276–277.

- ↑ Sword 1992, pp. 269–271.

- ↑ Werner 2013.

- ↑ Battles & Leaders 1987, p. 472.

- ↑ Sword 1992, p. 351.

- ↑ Sword 1992, pp. 373–376.

- ↑ Sword 1992, p. 378.

- 1 2 3 Annual Report 1866, p. 277.

- ↑ Jordan 2019, p. 229.

References

- Annual Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Missouri. Jefferson City, Mo.: Emory S. Foster Public Printer. 1866. pp. 274–277. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. Vol. 4. Secaucus, N.J.: Castle. 1987 [1883]. ISBN 0-89009-572-8.

- Boatner, Mark M. III (1959). The Civil War Dictionary. New York, N.Y.: David McKay Company Inc. ISBN 0-679-50013-8.

- Dyer, Frederick H. (1908). A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion: 44th Missouri Infantry. Des Moines, Iowa: Dyer Publishing Co. p. 1337. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- Jordan, Daniel W. III (2019). Operational Art and the Campaign for Mobile, 1864-1865: A Staff Ride Handbook (PDF). Fort Leavenworth, Kan.: Combat Studies Institute Press, US Army Combined Arms Center. ISBN 9781940804545. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- "Official Army Register of the Volunteer Force of the United States Army, Part VII". Washington, D.C.: Secretary of War. 1867. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- Werner, Bob (2013). "Missouri in the Civil War – the 44th Missouri Infantry". ourgrampascivilwar. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- Sword, Wiley (1992). The Confederacy's Last Hurrah: Spring Hill, Franklin, and Nashville. New York, N.Y.: University Press of Kansas for HarperCollins. ISBN 0-7006-0650-5.

Further reading

- Dyer, Frederick H. (2016) [1908]. A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion: 44th Regiment Missouri Infantry. Civil War Archive. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

External links

- Gertner, Larry (2019). "44th Missouri Infantry". Historical Marker Database. Retrieved July 29, 2020. This link shows the 44th Missouri historical marker.