| 60th Guards Rifle Division | |

|---|---|

| Active | 1943–1946 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Division |

| Role | Infantry |

| Engagements | Operation Little Saturn Operation Gallop Third Battle of Kharkov Donbas Strategic Offensive (August 1943) Battle of the Dniepr Nikopol–Krivoi Rog Offensive Uman–Botoșani Offensive First Jassy-Kishinev Offensive Second Jassy-Kishinev Offensive Vistula-Oder Offensive Battle of Berlin |

| Decorations | |

| Battle honours | Pavlograd |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Maj. Gen. Dmitrii Petrovich Monakhov Maj. Gen. Vasilii Pavlovich Sokolov |

The 60th Guards Rifle Division was formed as an elite infantry division of the Red Army in January, 1943, based on the 2nd formation of the 278th Rifle Division, and served in that role until after the end of the Great Patriotic War.

The division was formed in the 3rd Guards Army of Southwestern Front and immediately continued operations in the Soviet winter counteroffensive. In the spring of the year the Front was forced over to the defensive, but by August the division was part of the 1st Guards Army, fighting into the Donbas and towards the Dniepr River, winning a battle honor in the process. From late October into late November the 60th Guards helped force several crossings of that river in the Zaporozhe area and several dozen personnel were awarded the gold star as Heroes of the Soviet Union. During the winter it took part in the fighting around Krivoi Rog in the Dniepr bend, now as part of the 6th Army in the redesignated 3rd Ukrainian Front. In May, 1944 as it reached the Romanian border the division was assigned to the 32nd Rifle Corps of 5th Shock Army and it would remain under those commands for the duration of the war. In August the 60th Guards took part in the offensive that drove Romania out of the Axis and then was moved with its Army northward to join the 1st Belorussian Front. In its third winter offensive it advanced across Poland and eastern Germany to the Oder River, and then continued the assault into the northern sector of Berlin in April, 1945.

Following the German surrender the division formed part of the Allied occupation force in the city, including guarding Spandau Prison after the Nuremberg trials. The division was disbanded in December 1946.

Formation

The 60th Guards officially received its Guards title on January 3. Once the division completed its reorganization its order of battle was as follows:

- 177th Guards Rifle Regiment (from 851st Rifle Regiment)

- 180th Guards Rifle Regiment (from 853rd Rifle Regiment)

- 185th Guards Rifle Regiment (from 855th Rifle Regiment)

- 132nd Guards Artillery Regiment (from 847th Artillery Regiment)[1]

- 65th Guards Antitank Battalion (later 65th Guards Self-Propelled Artillery Battalion)

- 75th Guards Antiaircraft Battery (until May 10, 1943)

- 63rd Guards Reconnaissance Company

- 72nd Guards Sapper Battalion

- 91st Guards Signal Battalion

- 69th Guards Medical/Sanitation Battalion

- 64th Guards Chemical Defense (Anti-gas) Company

- 67th Guards Motor Transport Company

- 58th Guards Field Bakery

- 57th Guards Divisional Veterinary Hospital

- 1688th Field Postal Station

- 1114th Field Office of the State Bank

The 177th Guards Rifle Regiment was originally designated as the 178th, but this number had already been allocated to the 58th Guards Rifle Division a few days earlier.[2] Col. Dmitrii Petrovich Monakhov remained in command of the division and was promoted to the rank of major general two days later. The division did not complete its reorganization as a Guards division and receive its banner until February 13.[3]

Operation Little Saturn

On January 8 the commander of Southwestern Front, Col. Gen. N. F. Vatutin, reported to the STAVKA on his plans to further develop the winter counteroffensive:

The enemy along the Morozovskii and Shakhty axes is completing the withdrawal of his defeated forces behind the Northern Donets... The 3rd Guards Army, additionally reinforced with the 2nd and 23rd Tank Corps and the 346th Rifle Division, is to launch its main attack with the forces of the 59th and 60th Guards Rifle Divisions, the 266th Rifle Division, the 94th Rifle Brigade, and the 23rd and 24th Tank Corps... along the front Sharpaevka - Gusynka toward the front Verkhnyaya Tarasovka - Glubokii, and then in the direction of Gundorovskaya and Krasnyi Sulin.

During the month the division was paired with the 203rd Rifle Division to form Group Monakhov. Vatutin further reported on January 30 that the Group was tying down Axis forces along the sector Nizhnii Vishnevetskii to Kalitvenskaya and coming under repeated counterattacks by up to a battalion of infantry supported by 10-18 tanks and 4-6 bombers.[4]

By the beginning of February the 3rd Guards Army held a bridgehead over the Northern Donets south of Voroshilovgrad from which it broke out on February 12 in a drive to liberate that city. By February 20 the division was on the right (north) flank of the Army north of Pervomaisk, facing elements of the German XXX Army Corps. General Vatutin reported that the 60th and 61st Guards Divisions, 279th Rifle Division and 229th Rifle Brigade had conducted a regrouping overnight and into the morning before going over to the attack at 1600 hours from the Kripaki and Smelyi front towards Krivorozhe.[5] However, on the same day the German 4th and 1st Panzer Armies began the counteroffensive that would become the Third Battle of Kharkov. While this was primarily aimed at Voronezh Front, Southwestern Front also faced attacks and the overall crisis made any further Soviet advance impossible.[6] In the general crisis the 60th Guards was reassigned to the 19th Rifle Corps in 1st Guards Army and on February 28 it was reported as having withdrawn from the Malaia Kamyshevakha and Sukhaia Kamenka line to the Dmitrievka, Brazhevka, Suligovka and Dolgenkaia regions to organize a defense along that line. The Corps soon formed a second defensive line as well and was able to hold there as the main German offensive rolled northward.[7]

Into Ukraine

On March 1 the division was transferred to the 6th Guards Rifle Corps, still in 1st Guards Army. It remained in that Corps until June, when it became a separate division under Army command and was still there in early August when the Donbas Offensive began on the 13th.[8] It helped 1st Guards Army force a crossing of the Donets but was soon transferred to the 67th Rifle Corps of the 12th Army, which had been in the Front reserves. Under these commands it drove across the eastern Ukrainian plains towards Dniepropetrovsk and the Dniepr bend.[9][10] During this advance, on September 18, while serving in 12th Army's 66th Rifle Corps, the 60th Guards was awarded the honorific "Pavlograd" in recognition of its role in the second liberation of that city.[11]

By the beginning of October the division was under direct command of 12th Army, which was reduced to just four rifle divisions.[12] It had just run up against a bridgehead that the German forces were attempting to hold on the east bank of the Dniepr east of Zaporozhe. The STAVKA demanded that this bridgehead be eliminated as quickly as possible. The Front commander, Army Gen. R. Ya. Malinovsky, asked for and was granted the use of the 8th Guards Army for this purpose, stating that with it he could take the objective "in two days". The attack began at 2200 hours on the night of October 13 with 8th Guards in the center, 12th Army advancing from the north and 3rd Guards Army from the south. Malinovsky met his deadline with time to spare as 1st Panzer Army's forces abandoned Zaporozhe, destroying the dam and the railway bridge as they withdrew to the west bank.[13] On October 14 the division was awarded the Order of the Red Banner in recognition of its general meritorious service.[14]

Dniepr Operations

..gif)

Meanwhile much of the rest of Southwestern Front (redesignated as 3rd Ukrainian Front on October 20) liberated Dnepropetrovsk and Dneprodzerzhinsk.[15] The 60th Guards now faced Khortytsia, the largest island in the Dniepr at 12.5 km (7.8 mi) long and 2.5 km (1.6 mi) wide, dividing the river into two channels. On the night of October 24/25 the 185th Guards Regiment, led by Lt. Col. Semyon Mikhailovich Vilkhovsky, the 177th Guards Regiment, and the 5th Separate Penal Battalion, crossed to the island and established a bridgehead on its southern and southeastern end. This position was hit by savage German counterattacks and after three days was no longer tenable; the Soviet forces were withdrawn to the east bank.[16]

In November the headquarters of 12th Army was disbanded and its forces came under command of 6th Army.[17] The German Army Group South continued to hold another east-bank bridgehead based on Nikopol. In order to outflank and eliminate this position the 3rd Ukrainian Front again planned to force the Dniepr to the north. On the night of November 26/27 the 60th Guards advanced onto Khortytsia along with the 333rd Rifle Division to its south and both divisions staged a crossing to the west bank under strong German artillery and machine gun fire. Vilkhovsky's 185th Guards Regiment again led the way and established a small bridgehead near the village of Razumovka, 20 km (12 mi) south of Zaporozhe. This success allowed the rest of the Division to cross and over the following days the 60th and the 333rd Divisions carved out a deep bridgehead despite several German counterattacks with armor support. In recognition of his leadership and courage, on February 22, 1944 Lt. Col. Vilkhovsky was made a Hero of the Soviet Union.[18]

Among the many soldiers of the Division who became Heroes of the Soviet Union during the Dniepr operations was Lt. Afanasii Petrovich Shilin, the chief of intelligence of the 132nd Guards Artillery Regiment. During the initial crossing to Khortytsia on October 24/25 his radio station was destroyed during a German counterattack but he then led his men in an assault in which he personally killed seven German soldiers. He then recrossed the river and returned with a replacement radio and also led a telephone line to his position on the island. Shilin went on to lead the fighting against the German counterattacks until the island was evacuated. On February 22, 1944 he was made a Hero of the Soviet Union for his part in these actions. In January 1945, during the Vistula-Oder Offensive, Shilin would again distinguish himself in close combat and was made a Hero of the Soviet Union for the second time, a very unusual distinction for a junior officer.[19]

In December the 60th Guards returned to 66th Rifle Corps, which included all four divisions in 6th Army.[20] On December 29 General Monakhov handed his command to Maj. Gen. Vasilii Pavlovich Sokolov. Monakhov went on to command the 28th Guards Rifle Corps before dying of wounds on February 18, 1944. Meanwhile, Sokolov remained in command of the 60th Guards into the postwar.

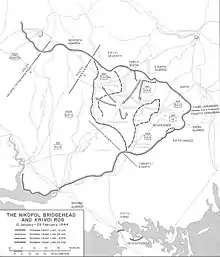

Nikopol-Krivoi Rog Offensive

3rd Ukrainian Front's first effort to renew the drive on Krivoi Rog began on January 10, led mainly by 46th Army, but made only modest gains at considerable cost and was halted on the 16th. The offensive was renewed on January 30 after a powerful artillery preparation against the positions of the XXX Army Corps on the same sector of the line, but this was met with a counter-barrage that disrupted the attack. A new effort the next day, backed by even heavier artillery and air support, made progress but still did not penetrate the German line. The Nikopol bridgehead had been weakened by transfers to other sectors and 4th Ukrainian Front drove a deep wedge into its south end. On February 4 the German 6th Army ordered the bridgehead to be evacuated.[21] The 60th Guards was by now again a separate division in 6th Army.[22]

During February the 6th Army was strengthened and the division was assigned to the 32nd Rifle Corps, joining the 259th and 266th Rifle Divisions.[23] It would remain in this Corps for the duration. The battle for Krivoi Rog continued until the end of that month. On March 4 all four of the Ukrainian fronts began a new offensive into western Ukraine. By March 20 the 3rd Ukrainian had reached the Southern Bug River.[24] During this advance the 32nd Corps was transferred to the 46th Army.[25]

Jassy-Kishinev Offensives

By the beginning of April the 46th Army was approaching the Dniestr River, the border with the Romanian-held territory of Moldova. On April 8 General Malinovsky ordered the Army to advance as quickly as possible to a wide sector north and south of Tiraspol with the objective of forcing a crossing of the river and capturing several German strongholds on the west bank in support of 37th Army's advance on Chișinău. By early on April 11 the Army was pursuing disorganized German forces across the river with 32nd Corps on its left (south) flank; it reached the river late in the day opposite Olănești with the 60th Guards in the second echelon. Its immediate objective was to capture this stronghold but faced several formidable problems in doing so. The Dniestr's floodplain extended up to 5 km (3.1 mi) east of the eastern bank and was largely under water, while the floodplain on the west bank was less than 1 km (0.62 mi) wide and was dominated by high ground of 150m-175m. Despite this the Corps began preparing to cross the next morning. In this effort the 259th and 266th Divisions seized meagre footholds near Olănești but the flooded ground on the east bank hindered and sometimes totally prevented the forward movement of heavy weapons, equipment and ammunition. The offensive was halted before the 60th Guards was committed.[26]

General Malinovsky now made plans to renew the offensive on April 19. 46th Army would attack in support of 5th Shock Army's assault on the fortified village of Cioburciu even though it was still facing both strong enemy resistance and deep waters across its front. 32nd Corps faced the 153rd Field Training Division of the German XXIX Army Corps. In the event the inclement weather and associated logistical issues forced the Army to postpone its attack until April 25. When it finally began the 266th Division managed to advance up to 3 km (1.9 mi) just north of Purcari but nowhere did the advance reach the vital high ground and the offensive ended in stalemate.[27]

By now the 2nd Ukrainian Front was also stalled on the Târgu Frumos axis towards Iași. Malinovsky was ordered to continue the push towards Chișinău sometime between May 15-17. In preparation the 3rd Ukrainian carried out a complex regrouping of its forces to concentrate the 8th Guards and 5th Shock Armies north of Grigoriopol. As part of this movement the 32nd Rifle Corps, now consisting of the 60th Guards, 259th and 416th Rifle Divisions, was transferred to 5th Shock; it would remain in this Army for the duration. The regrouping was carried out one rifle corps at a time, given the terrain and logistic restraints, and the 32nd Corps did not begin its move to the north until about May 10. Before the Corps could arrive the 8th Guards Army faced heavy counterattacks by German armor, and the 34th Guards Rifle Corps of 5th Shock Army was almost wiped out in the "bottle" loop of the Dniestr north of Grigoriopol. The best the 32nd Corps could do was to cover the remnants of the defeated divisions as they escaped east of the river. 3rd Ukrainian Front now went over to the defensive.[28]

Second Jassy-Kishinev Offensive

Over the following months the Front rebuilt and replenished its forces to prepare for a new offensive that would divide the German 6th Army from the Romanian 3rd Army, eliminating the latter and capturing Chișinău before advancing into pre-war Romania. While the overall offensive was set to begin on August 20, 5th Shock Army was not part of the Front's shock group and in the first days was to make holding attacks against elements of 6th Army. When the time came 5th Shock's commander, Lt. Gen. N. E. Berzarin, planned to launch its main attack with the 32nd Rifle Corps along a 6km-wide breakthrough front from Puhăceni to Speia; the Corps was facing elements of the German 294th and 320th Infantry Divisions. The attack was supported by the 266th Rifle Division and was planned on a daily schedule of advances. The Corps began its regrouping into the assault front on the night of August 20/21 and completed it by the end of the next day.[29]

5th Shock began its attack during the night of August 22/23 as the Axis Chișinău grouping was facing encirclement by the shock groups of 3rd and 2nd Ukrainian Fronts. 32nd Corps advanced on the city from the east although the 26th Rifle Corps reached it first by the end of the 23rd. At the same time the 32nd Corps forced a crossing of the Byk River and cut the railroad between Bender and Chișinău. The Army was ordered to continue its advance through the night, capture the city the next day and push forward to a line from Starke Dragusanu to Pozhoren by 1500 hours. Chișinău was officially cleared by 0400 hours.[30] Two regiments of the 60th Guards were awarded honorifics on this date:

"KISHINEV... 177th Guards Rifle Regiment (Lt. Colonel Kosov, Vasilii Nikolaevich)... 132nd Guards Artillery Regiment (Major Zemlyanskii, Vladimir Afanasevich)... The troops who participated in the liberation of Kishinev, by the order of the Supreme High Command of 24 August 1944, and a commendation in Moscow, are given a salute of 24 artillery salvoes from 324 guns."[31]

Three units of the division would be awarded decorations on September 7 for their parts in the battles for Bender and Chișinău: the 180th Guards Rifle Regiment received the Order of the Red Banner; the 185th Guards Rifle Regiment was given the Order of Bogdan Khmelnitsky, 2nd Degree; and the 72nd Guards Sapper Battalion was granted the Order of the Red Star.[32]

Over the following days 5th Shock was involved in the fighting to eliminate the now-encircled Chișinău grouping. By the end of August 24 it had reached the right bank of the Botna River, with the 32nd Corps on a line from Bardar to Khanul Veke. The encircled forces planned to break out to the west on the night of August 24/25. In order to counter this the Army was ordered to maintain its advance, with the 32nd Corps bending its left flank as far as Mericheni. About 37,000 German troops were within the pocket and while several thousands were able to escape at least temporarily the German 6th and the Romanian 3rd Armies had been effectively destroyed.[33]

In the aftermath of the offensive the 5th Shock Army was moved to the Reserve of the Supreme High Command. While there the 65th Guards Antitank Battalion was reequipped with SU-76 vehicles, becoming the 65th Guards Self-Propelled Artillery Battalion. In October the Army came under the command of the 1st Belorussian Front, where it would remain for the duration.[34][35]

Into Poland and Germany

In preparation for the Vistula-Oder Offensive in January 1945 the 5th Shock Army was moved into the bridgehead on the west bank of the Vistula at Magnuszew that had been seized by 8th Guards Army the previous August. The Army, supported by the artillery of the 2nd Guards Tank Army, was to break through the German main defensive zone on a 6km-wide front between Wybrowa and Stszirzina and secure the passage of 2nd Guards Tank through the breach. It was then to develop its attack in the general direction of Branków, Goszczyn and Błędów on the first day. Once the breakthrough was made the armor units and subunits in direct support of the Army's infantry were to unite as a mobile detachment to seize the second German defensive zone from the march.[36]

The offensive began at 0855 hours on January 14 with a reconnaissance-in-force following a 25-minute artillery preparation by all the Front's artillery. On the 5th Shock's and 8th Guards' sectors this quickly captured 3-4 lines of German trenches. The main forces of these armies took advantage of this early success and began advancing behind a rolling barrage, gaining as much as 12–13 km (7.5–8.1 mi) during the day and through the night before going over to the pursuit on January 15.[37] Two days later the 60th Guards took part in the liberation of the towns of Sochaczew, Skierniewice and Łowicz; in recognition of this on February 19 the 177th Guards Rifle Regiment would receive the Order of the Red Banner while the 65th Guards Self-Propelled Artillery Battalion was awarded the Order of Bogdan Khmelnitsky, 3rd Degree.[38]

During January 18-19 the Front's mobile forces covered more than 100 km (62 mi) while the combined-arms armies advanced 50–55 km (31–34 mi). On January 26 the Front commander, Marshal G. K. Zhukov, informed the STAVKA of his plans to continue the offensive. 5th Shock Army would attack in the general direction of Neudamm and then force the Oder River in the area of Alt Blessin before continuing to advance towards Nauen. On January 28 the 2nd Guards Tank and 5th Shock Armies broke through the Pomeranian Wall from the march and by the end of the month reached the Oder south of Küstrin and seized a bridgehead 12 km (7.5 mi) in width and up to 3 km (1.9 mi) deep. This would prove to be the limit of 5th Shock's advance until April.[39]

Battle of Berlin

At the start of the Berlin operation the 5th Shock was one of four combined-arms armies that made up the main shock group of 1st Belorussian Front. The Army deployed within the Küstrin bridgehead along a 9km-wide front between Letschin and Golzow and was to launch its main attack on its left wing on a 7 km (4.3 mi) sector closer to the latter place. The 32nd Corps had the 60th Guards and 295th Divisions in the first echelon and the 416th in the second. All three divisions had between 5,000 and 6,000 personnel on strength. The Army had an average of 43 tanks and self-propelled guns on each kilometre of the breakthrough front.[40]

In the days just before the offensive the 3rd Shock Army was secretly deployed into the bridgehead which required considerable regrouping and covering operations by elements of 5th Shock. The Army then occupied jumping-off positions for a reconnaissance-in-force by battalions of five of its divisions, including the 60th Guards and 295th Divisions, which began early on the morning of April 14. After stubborn fighting the battalion of the 60th Guards, having advanced 1.5 km (0.93 mi), captured the railway platform 1 km (0.62 mi) southeast of Zechin. The next day these reconnaissance battles continued along the entire front. The forces of the division, along with those of the 94th Guards and 266th Rifle Divisions, overcame German resistance and advanced from 1 km (0.62 mi) to 3 km (1.9 mi) and reached a line from marker 8.2 to marker 8.7 to the house southeast of Buschdorf. In the course of these two days of limited fighting the Front's troops had advanced as much as 5 km (3.1 mi), ascertained and partly disrupted the German defensive system, and had overcome the thickest zone of minefields. The German command was also misled as to when the main offensive would occur.[41]

In the event that offensive began the following day. 5th Shock attacked at 0520 hours, following a 20-minute artillery preparation and with the aid of 36 searchlights. 32nd Corps advanced 8 km (5.0 mi) and by the end of the day had reached the east bank of the Alte Oder. As a whole the Army broke through all three positions of the main German defensive zone, reached the second defensive position, and captured 400 prisoners. On April 17 the Corps assisted the 1st Mechanized Corps in forcing the Alte Oder and went on to occupy a line from the west bank of the Stafsee to northeast of Hermersdorf. This advance penetrated the second defensive position. The next day 5th Shock resumed its offensive at 0700 hours, following a 10-minute artillery preparation. 32nd Corps was now supported by a brigade of 11th Tank Corps and advanced another 3 km (1.9 mi) during the day. During April 19 the Corps was involved in heavy fighting with units of the 11th SS Panzergrenadier Division Nordland which had been committed from reserve. Despite heavy counterattacks supported by groups of 10-12 tanks the Corps advanced 9 km (5.6 mi) and broke through the third German defensive zone, reaching the northwestern tip of the Scharmützelsee.[42]

32nd Rifle Corps, along with two brigades of 11th Tank Corps, completed its breakthrough of the third zone during the night. On April 20 it continued attacking to the west with all its divisions deployed. Having repulsed four counterattacks by German tanks and infantry it advanced 7 km (4.3 mi). The next day the 5th Shock broke into the clear and 32nd Corps covered 23 km (14 mi), captured Strausberg in cooperation with elements of the 26th Guards Rifle Corps and by the end of the day entered the northeastern outskirts of Berlin in the area of the Marzahn and Wuhlgarten suburbs. During April 22 the Corps advanced up to 1.5 km (0.93 mi) into the city and was fighting in the eastern part of Friedrichsfelde, breaking through the city's interior defense line. The next day it reached the east bank of the Spree following an advance of another 3 km (1.9 mi). During April 26 the 26th Guards and 32nd Corps fought along the north bank of the Spree, advancing in fighting about 600m and by the end of the day reached the Kaiserstrasse and Alexanderstrasse. During the next day the two corps, following furious fighting, were able to advance no more than 400-500m along a narrow 500m sector, and on April 28 managed to clear just several blocks.[43] But by now the German position in Berlin was much more than hopeless and after the capitulation on May 2 the 180th Guards Rifle Regiment (Maj. Kyzov, Demyan Vasilevich), 185th Guards Rifle Regiment (Lt. Col. Milov, Pavel Ivanovich) and the 65th Guards Self-Propelled Artillery Battalion (Maj. Filippovich, Ivan Fedorovich) were granted its name as an honorific.[44]

Postwar

When the fighting stopped the men and women of the division shared the full title of 60th Guards, Pavlograd, Order of the Red Banner Division. [Russian: 60-я гвардейская стрелковая Павлоградская Краснознамённая дивизия.] On May 28 the division was awarded the Order of Suvorov, 2nd Degree, for its part in the capture of Berlin.[45] On May 29 General Sokolov was made a Hero of the Soviet Union.[46] The division was disbanded in December 1946,[47] along with much of the 5th Shock Army.[48] A company from the 185th Guards Rifle Regiment may have been used to form the 137th Separate Commandant's Guard Battalion of the Soviet Military Administration in Germany, which was later expanded into the 6th Separate Motor Rifle Brigade. The latter officially inherited the traditions of the 185th Guards in 1982 and became the 6th Separate Guards Motor Rifle Brigade.[49]

References

Citations

- ↑ Charles C. Sharp, "Red Guards", Soviet Guards Rifle and Airborne Units 1941 to 1945, Soviet Order of Battle World War II, Vol. IV, Nafziger, 1995, p. 69

- ↑ Perechen No. 5; see Bibliography

- ↑ Sharp, "Red Guards", p. 69

- ↑ Soviet General Staff, Rollback, ed. & trans. R. W. Harrison, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2015, Kindle ed., Part VI, sections 8, 20

- ↑ David. M. Glantz, After Stalingrad, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2011, pp. 150, 162

- ↑ John Erickson, The Road to Berlin, Weidenfeld and Nicolson Ltd., London, UK, 1983, pp. 49-54

- ↑ Glantz, After Stalingrad, pp. 185, 189, 194

- ↑ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1943, pp. 65, 113, 138, 164, 196

- ↑ Sharp, "Red Guards", p. 69

- ↑ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1943, p. 225

- ↑ http://www.soldat.ru/spravka/freedom/1-ssr-5.html. In Russian. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ↑ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1943, p. 253

- ↑ Erickson, The Road to Berlin, pp. 138-39

- ↑ Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967a, p. 217.

- ↑ Soviet General Staff, The Battle of the Dnepr, ed. & trans. R. W. Harrison, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2018, pp. 77, 80

- ↑ http://www.warheroes.ru/hero/hero.asp?Hero_id=11758. In Russian; English translation available. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ↑ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1943, p. 310

- ↑ http://www.warheroes.ru/hero/hero.asp?Hero_id=11758. In Russian; English translation available. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ↑ http://www.warheroes.ru/hero/hero.asp?Hero_id=3. In Russian: English translation available. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ↑ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1944, p. 19

- ↑ Earl F. Ziemke, Stalingrad to Berlin, Center of Military History United States Army, Washington, DC, 1968, pp. 240-42

- ↑ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1944, p. 48

- ↑ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1944, p. 78

- ↑ Ziemke, Stalingrad to Berlin, pp. 273-75, 277, 282-83

- ↑ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1944, p. 109

- ↑ Glantz, Red Storm Over the Balkans, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 2007, pp. 113, 133-35, 137

- ↑ Glantz, Red Storm Over the Balkans, pp. 143-44, 146-47, 157-58

- ↑ Glantz, Red Storm Over the Balkans, pp. 284-85, 287, 293, 304-14

- ↑ Soviet General Staff, The Iasi-Kishinev Operation, ed. & trans. R. W. Harrison, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2017, pp. 52-53, 83

- ↑ Soviet General Staff, The Iasi-Kishinev Operation, pp. 120-21, 123, 127

- ↑ http://www.soldat.ru/spravka/freedom/1-ssr-3.html. In Russian. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- ↑ Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967a, pp. 485–87.

- ↑ Soviet General Staff, The Iasi-Kishinev Operation, pp. 127, 134-37

- ↑ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1944, pp. 299, 315

- ↑ Sharp, "Red Guards", p. 69

- ↑ Soviet General Staff, Prelude to Berlin, ed. & trans. R. W. Harrison, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2016, pp. 40, 55, 573-75. Note this source misidentifies the Army as 5th Guards on p. 573.

- ↑ Soviet General Staff, Prelude to Berlin, pp. 72-73

- ↑ Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967b, pp. 230–31.

- ↑ Soviet General Staff, Prelude to Berlin, pp. 76, 82, 589-90. Note this source misidentifies the Army as 5th Guards at one point on p. 82.

- ↑ Soviet General Staff, The Berlin Operation 1945, ed. & trans. R. W. Harrison, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2016, Kindle ed., ch. 11

- ↑ Soviet General Staff, The Berlin Operation 1945, Kindle ed., ch. 12

- ↑ Soviet General Staff, The Berlin Operation 1945, Kindle ed., ch. 12

- ↑ Soviet General Staff, The Berlin Operation 1945, Kindle ed., ch. 15, 20

- ↑ http://www.soldat.ru/spravka/freedom/5-germany.html. In Russian. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- ↑ Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967b, p. 270.

- ↑ http://www.warheroes.ru/hero/hero.asp?Hero_id=3629. In Russian; English translation available. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ↑ Tsapayev & Goremykin 2014, pp. 463–465.

- ↑ Feskov et al. 2013, p. 382.

- ↑ Tolstykh, Viktor (23 June 2016). "Краткая история 6 гв. омсбр – 1962-1997 гг" [A Brief History of the 6th Guards Separate Motor Rifle Brigade, 1962–1997]. 10otb.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 28 May 2017.

Bibliography

- Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union (1967a). Сборник приказов РВСР, РВС СССР, НКО и Указов Президиума Верховного Совета СССР о награждении орденами СССР частей, соединениий и учреждений ВС СССР. Часть I. 1920 - 1944 гг [Collection of orders of the RVSR, RVS USSR and NKO on awarding orders to units, formations and establishments of the Armed Forces of the USSR. Part I. 1920–1944] (PDF) (in Russian). Moscow. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-03-27. Retrieved 2020-05-12.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union (1967b). Сборник приказов РВСР, РВС СССР, НКО и Указов Президиума Верховного Совета СССР о награждении орденами СССР частей, соединениий и учреждений ВС СССР. Часть II. 1945 – 1966 гг [Collection of orders of the RVSR, RVS USSR and NKO on awarding orders to units, formations and establishments of the Armed Forces of the USSR. Part II. 1945–1966] (in Russian). Moscow.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Feskov, V.I.; Golikov, V.I.; Kalashnikov, K.A.; Slugin, S.A. (2013). Вооруженные силы СССР после Второй Мировой войны: от Красной Армии к Советской [The Armed Forces of the USSR after World War II: From the Red Army to the Soviet: Part 1 Land Forces] (in Russian). Tomsk: Scientific and Technical Literature Publishing. ISBN 9785895035306.

- Grylev, A. N. (1970). Перечень № 5. Стрелковых, горнострелковых, мотострелковых и моторизованных дивизии, входивших в состав Действующей армии в годы Великой Отечественной войны 1941-1945 гг [List (Perechen) No. 5: Rifle, Mountain Rifle, Motor Rifle and Motorized divisions, part of the active army during the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945] (in Russian). Moscow: Voenizdat. pp. 184-85

- Main Personnel Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union (1964). Командование корпусного и дивизионного звена советских вооруженных сил периода Великой Отечественной войны 1941–1945 гг [Commanders of Corps and Divisions in the Great Patriotic War, 1941–1945] (in Russian). Moscow: Frunze Military Academy. pp. 320-21

- Tsapayev, D.A.; et al. (2014). Великая Отечественная: Комдивы. Военный биографический словарь [The Great Patriotic War: Division Commanders. Military Biographical Dictionary] (in Russian). Vol. 5. Moscow: Kuchkovo Pole. ISBN 978-5-9950-0457-8.