| 7th Anti-Tank Regiment | |

|---|---|

_M10_in_Italy.jpg.webp) An M10 tank destroyer of 7th Anti-Tank Regiment in Italy, 1 August 1944 | |

| Active | 1939–1945 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Anti-Tank Artillery |

| Size | Regiment |

| Part of | 2nd New Zealand Division |

| Engagements | Second World War |

| Insignia | |

| Distinguishing Patch | .svg.png.webp) |

| Vehicle Marking | .svg.png.webp) |

The 7th Anti-Tank Regiment was an anti-tank artillery regiment of the New Zealand Military Forces raised during the Second World War. It saw service as part of the 2nd New Zealand Division during the Greek, North African, Tunisian and Italian campaigns, before being disbanded in December 1945.

Formation

At the beginning of the Second World War, New Zealand intended to raise an anti-tank regiment, but did not possess any anti-tank guns with which to properly train the gunners. It was therefore decided in late 1939 to initially form and train an anti-tank battery in the United Kingdom from New Zealanders already present there.[1] This was 34 Battery, formed at Aldershot, and it later joined the First Echelon, 2nd New Zealand Expeditionary Force (2NZEF), in Egypt in April 1940.[2] Meanwhile, a further three batteries were formed in New Zealand. One of these, 33 Battery, travelled with the Third Echelon, 2NZEF, and joined 34 Battery in September for further training in Egypt.[3] The other two, 31 and 32 Batteries, were sent to the UK for training and only joined the rest of the regiment in February 1941.[4] Now assembled, 7th Anti-Tank Regiment became part of the New Zealand Division and consisted of an HQ battery and four anti-tank batteries. The anti-tank batteries were further broken down into three troops,[Note 1] each armed with four 2-pounder anti-tank guns. In the case of 34 Battery, the guns were mounted onto 30-cwt trucks, known as portées.[5]

Greece

Italy had tried to invade Greece in October 1940, but had so far failed to be victorious. The British Government anticipated that Germany would intervene and decided to send a commonwealth military force, known as W Force, to support Greece.[6] In April 1941, 7th Anti-Tank Regiment and the rest of the New Zealand Division were tasked with defending part of the Aliakmon Line. The German invasion began on 6 April and quickly broke through the Greek defenders near Florina, threatening the left flank of W force. The New Zealand Division was forced to pull back to the Olympus line on 8 April.[7] 31, 32 and 33 Batteries were distributed among the 4th, 5th and 6th New Zealand Infantry Brigades respectively and were subsequently engaged in a series of battles at Servia and Olympus passes.[8] On the night of the 17/18th the New Zealand Division was order to withdraw to Thermopylae.[9] 34 Battery, operating with the divisional cavalry, helped to cover the withdrawal and knocked out the regiment's first enemy tank on 18 April.[10] At least two further enemy tanks were also knocked out that day by L troop during another rear guard action at Tempe.[11]

With the worsening situation in Greece, a decision had been made on 21 April to evacuate the commonwealth forces from Greece. Initially the start date for the evacuation was set for the night of 28/29, but after the surrender of Greece on 23 April, it was brought forward to the night of 24/25 [12] The withdrawal would not be complete before 7th Anti-Tank Regiment was engaged in a further attack by the Germans on 24 April. The 25 remaining 2-pounder guns (of the original 48)[13] were placed in defensive positions on the high ground around Molos[14] and at least 12 German tanks were knocked out.[15] After the battle, the New Zealand Division withdrew to the evacuation beaches. 7th Anti-Tank Regiment was finally evacuated to Crete by HMS Havock on 28 April.[16] During the Battle of Greece, the regiment had lost 19 killed, 22 wounded and 75 taken prisoner.[17]

North Africa

Reorganisation

Although the majority of the New Zealand Division would take part in the Battle of Crete, 7th Anti-Tank Regiment was evacuated to Egypt prior to the battle.[18] In Egypt the regiment acquired new 2-pounder gun portées (previously only 34 Battery had portées) and was brought up to strength with reinforcements. A fourth troop was also added to each battery,[Note 2] but, unlike the first three troops, were instead equipped with 18-pounder guns converted to be used in the anti-tank role.[19] In September 1941 the New Zealand Division took over the Baggush Box, a defensive position on the Libyan coast. Training would nonetheless continue until November in anticipation of an offensive against the Germans and Italians in Libya.[20]

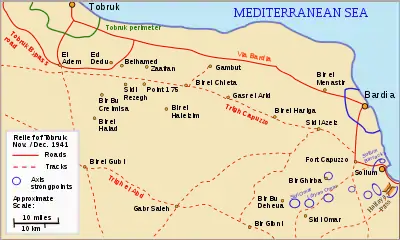

Operation Crusader

Operation Crusader was the planned offensive to lift the siege of Tobruk. The New Zealand Division was assigned to XIII Corps, tasked with cutting off the axis formations along the northern part of the Libyan frontier. Meanwhile, the armoured units of XXX Corps were to advance west from the southern portion of the frontier, engage and destroy the armoured units of the Afrika Korps, and link up with the 70th Division defending Tobruk.[21] As in Greece, 31, 32 and 33 Batteries were allotted to the 4th, 5th and 6th brigades respectively. 34 Battery was dispersed, with P and N troops assigned to the divisional cavalry, and O and Q troops held by the division.[22]

The offensive began on 18 November 1941 and by the 21st, the New Zealand Division had swung around behind the Italian 55th (Savona) Division and moved north east, cutting the Via Balbia and encircling the port of Bardia.[23] Late on the 21st orders were sent for 6th Brigade to advance west to Sidi Rezegh, where the support group of 7th Armoured Division had been surrounded. The next day 4th Brigade were also sent west to capture Gambut.[24] On the 22nd, 6th Brigade began the day by inadvertently overrunning the Afrika Korps headquarters. K troop, with 25th Battalion, was then sent northwest to take point 175 and L troop, with 26th Battalion, was sent southwest towards Sidi Rezegh.[25] The New Zealanders linked up with the 5th South African Brigade and were in position in time for a major attack by the 21st Panzer Division. During the battle, L troop, in what the official history describes as “an anti-tank action that must rank among the finest in the war”, and broadly verified by German reports, knocked out 24 enemy tanks.[26][27] During the night of the 26th/27th two guns from N troop (detached from the divisional cavalry), along with 19th Battalion and a squadron of 44th Royal Tank Regiment finally linked up with units from the Tobruk garrison at El Duda.[28]

Meanwhile, the German 21st and 15th Panzer Divisions had launched a daring attack hooking around the XXX Corps units at the frontier.[29] 5th Brigade and two squadrons of the divisional cavalry had remained around Bardia and now faced an armoured attack from the east. On the morning of the 27th the divisional cavalry spotted some 40 enemy tanks heading towards 5th Brigade headquarters at Sidi Aziz. It was too late for the brigade HQ to move, but the anti-tank guns from the divisional cavalry (two guns from each of N and P troops) decided to help defend the position. The defence was forlorn and the position quickly overrun. All four guns were quickly knocked out and the survivors from 34 Battery were taken prisoner (along with the rest of the headquarters).[30]

4th and 6th Brigades would experience heavy fighting over the coming days. The divisional headquarters at Zaafran was also subject to attacks. Lieutenant Colonel Oakes, the commander of 7th Anti-Tank Regiment, would lead “B Group” (an ad hoc group of soldiers from O and Q troops, and half a troop from 14th Light AA Regiment acting as infantry) in defending the headquarters.[31] On the 30th, 15th Panzer Division launched a major attack. The guns of 33 Battery were poorly organised and 6th Brigade was overrun.[32] Having taken heavy casualties, the New Zealand Division withdrew from the battle on the night of the 1/2 December, returning to Baggush without incident.[33] A and B troops with 18th Battalion, and 2 guns from N troops with part of 19th Battalion were split off from the rest of the division during the fighting on 1 December and forced to withdraw west into Tobruk.[34] These units helped to defend Tobruk until they returned to the New Zealand Division in late-December.[35]

During Operation Crusader, 7th Anti-Tank Regiment had lost 49 killed, 76 wounded and 61 taken prisoner – roughly a quarter of the regiment's strength. Among the dead was Oakes, who was killed by artillery fire on 30 November.[36] In January 1942, Bardia would be captured by the allies, freeing 1171 commonwealth prisoners,[37] included most of the men from 34 Battery who had been captured at Sidi Aziz.[36]

Mersa Matruh

Following Operation Crusader, the New Zealand Division was withdrawn to Syria as a precaution against a possible German invasion through Turkey.[38] In June the allied forces in Libya were defeated at the Battle of Gazala and forced to retreat. The New Zealand Division was rapidly redeployed back to Egypt and help hold the Mersa Matruh line.[39] Unfortunately 7th Anti-Tank Regiment was not ready for combat. The regiment was undergoing a reorganisation in which it would be rearmed with 64 new 6-pounder anti-tank guns. It had not received any of the new guns, nor had any of its personnel completed the 6-pouder training course. The regiment was, however, able to liberate five 6-pounders from the anti-tank school where the men were being trained. 34 Battery also had no guns at all, having already returned its 2-pounders to the ordnance depot, and had to be left in reserve until it could be rearmed.[40]

On 26 June, the New Zealand Division moved to Minqar Qaim and the next day was attacked by the 21st Panzer Division.[41] During the fighting, twelve new 6-pounder guns arrived and were distributed amongst 31, 32 and 33 Batteries. The 6-pounders were still covered in grease (used to protect the guns from corrosion during transportation at sea) and many lacked gun sights.[42] By the end of the day the New Zealanders were encircled and forced to make a dramatic break out during the night. The breakout was successful and required all motorised transport, including the portées of 7th Anti-Tank Regiment, to help carry the infantry east.[43]

First El Alamein

Following the breakout at Minqar Qaim the New Zealand Division redeployed to the El Alamein line.[41] By July, 7th Anti-tank Regiment had received a further 22 6-pounder guns, but still operated a number of 2-pounders.[44] In mid-July the 2nd New Zealand Division[Note 3] took part in Operation Bacon. The plan was to capture Ruweisat Ridge and then advance into the enemy's rear. [46] 4th Brigade, with 31 Battery, was on the left and 5th Brigade, with 33 Battery, was on the right. [47] The New Zealanders advanced on the evening of 14 July and by morning had taken the ridge and captured 2000 Italians. The 15th Panzer Division then launched a counter-attack towards 4th Brigade. [46] The portées of 31 Battery were exposed, many were knocked out and the remaining guns were forced to pull back. The withdrawal of the anti-tank guns and the failure of the 2nd Armoured Brigade to arrive meant that most of 19th and 20th Battalions were forced to surrender.[48] The German counter-attack also extended to the left of 5th Brigade, where K troop had all of its guns knocked out and the surviving men were forced to surrender, along with most of 22nd Battalion.[49] A follow-up attack was made on the evening of 21 July against the El Mreir depression by 6th Brigade, with 32 Battery and two troops from 31 Battery.[50] In a repeat of Ruweisat Ridge, the infantry captured the objective but 2nd Armoured Brigade failed to arrive and consolidate the position. When the 21st Panzer Division counter-attacked at dawn on the 22nd, many of the anti-tank guns were knocked out and much of 6th Brigade was forced to surrender.[51] Due to the losses incurred, 32 Battery was temporarily disbanded and any survivors were dispersed amongst the rest of the regiment.[52]

Following first El Alamein, the front descended into a stalemate. During the lull the only notable action by the New Zealanders was a counter-attack against a last ditch offensive by the Axis forces at Alam el Halfa on 3 September.[53] Although 7th Anti-Tank Regiment took a number of casualties during the battle from artillery and minefields, it did not fire a single shot and was not seriously engaged.[54]

Second El Alamein

.jpg.webp)

After months of preparation, rearmament and reinforcement, Eighth Army launched Operation Lightfoot against the Axis forces on the evening of 23 October 1942. 32 and 33 Batteries were assigned to 5th and 6th Brigades respectively, and led the advance in the New Zealand sector towards Miteirya Ridge. [55] 31 Battery and 9th Armoured Brigade (under the command of 2nd New Zealand Division) then followed up to consolidate the position. The New Zealanders were relieved on the night of the 27th/28th in order to reorganise for the next attack, Operation Supercharge.[56]

In the meantime, 34 Battery, which had previously been held in reserve, was loaned to the Australian 20th Brigade to assist in their attack against a position known as Thompson's post. [57] 34 Battery returned on the evening of the 30/31st and, along with E troop of 31 Battery, was assigned to the British 151st Brigade.[Note 4] On 2 November, the 2nd New Zealand Division attacked towards the Rahman Track with 151st and 152nd Brigades. The 9th Armoured Brigade, with the rest of 31 Battery, then passed though the infantry and engaged a large number of Axis anti-tank guns.[58] In the ensuing battle, 31 Battery took approximately 30% casualties, while most of 9th Brigade's tanks were knocked out. [59]

Operation Supercharge proved to be a success and the Axis forces were forced into retreat. 31, 32 and 33 Batteries remained with their respective brigades during the pursuit across Libya, while 34 Battery returned to the divisional reserve. 7th Anti-Tank Regiment's casualties for the second battle of El Alamein were 11 killed and 59 wounded. [60][61]

Libya and Tunisia

Following the battle at El Alamein, Eight Army pursued the Axis forces across Libya. In mid-December, the New Zealanders tried to outflank and trap the Germans at El Agheila. Although engaged by 5th Brigade, only the guns of E troop were appropriately located to provide support and the German tanks escaped.[62] The regiment rested at Nofaliya from late-December and received a batch of new 17-pounder anti-tank guns, rearming one troop of each battery.[63] In January 1943, the regiment moved to Tripoli and was later deployed to defend the south and south-west of Medenine from a spoilingattack by the 10th Panzer Division on 6 March. Although 52 tanks were knocked out in the battle, none were accredited to 7th Anti-Tank Regiment.[64] Later the New Zealanders outflanked the Mareth line and forced the Axis forces into retreat once more. A noteworthy event during the pursuit was the disablement of a Tiger Tank by A troop of 31 Battery.[65] The Axis forces in Tunisia finally surrendered on 13 May 1943 and the regiment returned to Egypt.[66]

Italy

.jpg.webp)

Following recuperation in Egypt, the 2nd New Zealand Division was redeployed to Italy in October 1943.[67] The 17-pounders of 34 Battery covered the crossing of the Sangro river, pre-emptively destroying buildings which could be used as defensive positions by the Germans.[68] The regiment was otherwise mostly employed in menial tasks such as ammunition transport for the field regiments or providing small infantry detachments to garrison and patrol quiet parts of the front line. The 2nd New Zealand Division was moved to Cassino in mid-January 1944, but 7th Anti-Tank Regiment would continue much of the same roles.[69]

Following the breakthrough of the Gustav line in May 1944, the regiment's strength was altered. C, G, L and P troops were detached from their former batteries and merged into a new fifth battery, 39 Battery, equipped with 4.2 inch mortars. Later in June, A and D troops of 31 Battery were reequipped with M10 tank destroyers, while 33 Battery began to receive formal infantry training with the expectation that they would likely continue to receive intermittent employment as infantry.[70]

During the advance to the Gothic Line in June and July, 7th Anti-Tank Regiment would provide fire support to the infantry brigades, with the M10s being employed as assault guns and in the indirect fire role. Only twice did the regiment engage enemy tanks:[71] a Tiger tank was hit three times by a 17-pounder of Q troop, but was able to withdraw,[72] while a 17-pounder from M troop destroyed a Panzer IV – the only tank destroyed by the regiment in the entire Italian campaign.[73]

The reduced need for anti-tank support meant that the regiment underwent a further reorganisation in October 1944. 31, 32 and 33 Batteries were reduced to two troops[Note 5], one troop equipped with M10s and one with 17-pounders, while the obsolete 6-pounder guns were dropped from the establishment. 39 Battery was redesignated as 34 Battery and the original 34 Battery was disbanded, many of its men being transferred to the Divisional Cavalry Regiment (which was being reorganised as an infantry battalion).[71]

The regiment would spend the winter in defensive positions watching over the Senio river. In February 1945, the 17-pounders received high explosive ammunition, which made them much more effective against unarmoured targets and able to be used in the indirect fire role.[74] The spring offensive began on 9 April and meant that 7th Anti-Tank Regiment would finally be engaged in a set piece battle in Italy. 31, 32 and 33 Batteries were assigned to the 9th, 5th and 6th Brigades respectively. 5th and 6th Brigades initially lead the advance, but each brigade would in turn be rotated into reserve. 34 Battery was split into two sub-batteries, with one sub battery assigned to which ever of the two brigades were leading the advance.[75] The New Zealanders advanced into the Po Valley throughout April. The crossing of the river Po was led by 9th Brigade with 31 Battery and a sub battery of 34 Battery, although the M10 troop had to be left behind due to a lack of heavy bridging equipment.[76] The leading elements of 31 and 34 Batteries arrived in Trieste on 2 May, the same day as the German Surrender in Italy.[77]

Disbandment

The 2nd New Zealand Division initially remained in the Trieste area, but moved to Umbria in August 1945. Following the surrender of Japan on 2 September, 7th Anti-Tank Regiment rapidly reduced in size, although a few men were transferred to 25 Battery, which went to Japan as part of J Force (the New Zealand occupation force of Japan). On 1 December the remaining men were merged into the 4th Field Regiment and 7th Anti-Tank Regiment was formally disbanded on 18 December 1945. [78] During the war, the regiment lost a total of 154 men killed in action or died of wounds.[79]

Notes

- Footnotes

- ↑ The batteries were lettered sequentially, excluding the letter I, and with an extra letter reserved for a fourth troop, i.e. 31 Battery (A, B, C troops), 32 Battery (E, F, G troops), 33 Battery (J, K, L troops), 34 Battery (N, O, P troops).[5]

- ↑ The new troops were lettered D, H, M and Q for 31, 32, 33 and 34 batteries respectively.[19]

- ↑ The New Zealand Division was redesignated as the 2nd New Zealand Division on 8 July 1942 in order to confuse the enemy on the number of allied divisions present in Egypt.[45]

- ↑ 151st and 152nd Brigades had been assigned to the 2nd New Zealand Division for Operation Supercharge. 152nd Brigade had its own anti-tank support from 244 Battery, Royal Artillery.[58]

- ↑ The troops were also relettered sequentially, i.e. 31 Battery (A, B troops), 32 Battery (C, D troops), 33 Battery (E, F troops), 34 Battery (G, H, J, K troops).[71]

- Citations

- ↑ Historical Publications Branch 1949, pp. 208–212.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, p. 8.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, p. 12.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, pp. 8–11.

- 1 2 Murphy 1966, p. 22.

- ↑ "Greece and Crete, 1941". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Archived from the original on 2013-07-18. Retrieved 2022-01-02.

- ↑ McClymont 1959, p. 167.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, pp. 28–40.

- ↑ McClymont 1959, p. 282.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, p. 54.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, pp. 61–62.

- ↑ McClymont 1959, pp. 367–368.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, p. 74.

- ↑ McClymont 1959, p. 356.

- ↑ McClymont 1959, p. 393.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, p. 99.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, p. 101.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, p. 109.

- 1 2 Murphy 1966, pp. 178–179.

- ↑ Murphy 1961, p. 31.

- ↑ Cox 2015, p. 39.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, p. 182.

- ↑ Cox 2015, pp. 61–63.

- ↑ Murphy 1961, pp. 135–136.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, p. 199.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, pp. 205–208.

- ↑ Murphy 1961, p. 170.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, p. 232.

- ↑ Cox 2015, p. 105.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, pp. 242–246.

- ↑ Murphy 1961, p. 256.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, pp. 262–263.

- ↑ Cox 2015, p. 143.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, pp. 287.

- ↑ Cox 2015, p. 151.

- 1 2 Murphy 1966, pp. 296.

- ↑ Cox 2015, p. 154.

- ↑ Scoullar 1955, pp. 22–27.

- ↑ Latimer 2002, pp. 52–53.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, pp. 307–315.

- 1 2 Latimer 2002, p. 54.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, p. 319.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, p. 327.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, p. 334.

- ↑ Scoullar 1955, p. 198.

- 1 2 Latimer 2002, p. 67.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, p. 342.

- ↑ Scoullar 1955, p. 287-290.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, pp. 343–345.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, p. 350.

- ↑ Scoullar 1955, p. 364.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, p. 352.

- ↑ Latimer 2002, pp. 110–113.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, p. 368.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, p. 381.

- ↑ Latimer 2002, p. 239.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, pp. 398–401.

- 1 2 Latimer 2002, pp. 279–280.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, p. 408.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, p. 397.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, p. 421.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, pp. 443–444.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, p. 451.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, p. 471.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, p. 495.

- ↑ "Tunisia and victory". nzhistory.govt.nz. Retrieved 2022-02-01.

- ↑ "The Italian Campaign". nzhistory.govt.nz. Retrieved 2022-02-02.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, p. 526.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, pp. 515–590.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, pp. 590–592.

- 1 2 3 Murphy 1966, pp. 666–667.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, pp. 625.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, pp. 630–631.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, pp. 680–685.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, pp. 703–721.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, p. 722.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, p. 729.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, pp. 735–738.

- ↑ Murphy 1966, pp. 760–764.

References

- Documents Relating to New Zealand’s Participation in the Second World War 1939―45: Volume 1. Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–45. Wellington: Historical Publications Branch. 1949.

- Cox, P. (2015). Desert War: The Battle of Sidi Rezegh. Auckland: Exisle Publishing. ISBN 978-1-921966-70-5.

- Latimer, J. (2002). Alamein. London: John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-6203 1.

- McClymont, W. G. (1959). To Greece. Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–45. Wellington: Historical Publications Branch.

- Murphy, W. E. (1961). The Relief of Tobruk. Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–45. Wellington: Historical Publications Branch.

- Murphy, W. E. (1966). 2nd New Zealand Divisional Artillery. Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–45. Wellington: Historical Publications Branch.

- Scoullar, J. L. (1955). Battle For Egypt. Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–45. Wellington: Historical Publications Branch.