| 825th Tank Destroyer Battalion | |

|---|---|

| Active | 1942–1945 |

| Disbanded | 1945 |

| Country | USA |

| Allegiance | Army |

| Size | Battalion |

| Part of | Independent unit |

| Equipment | 3-inch Gun M5 |

| Engagements | World War II *Battle of the Bulge |

The 825th Tank Destroyer Battalion was a tank destroyer battalion of the United States Army active during the Second World War. It was organized as a towed battalion, with 3" anti-tank guns, and initially saw service during the Battle of Normandy as a rear-area security unit. Parts of the unit were sent into combat as part of an ad hoc task force on 16 December 1944, on the northern flank of the Ardennes Offensive, where it defended Amblève river bridges at Malmedy and Stavelot. It returned to security duties at the end of January 1945, and served in rear areas for the remainder of the war.

Early service

The battalion was activated in August 1942, and organized as a "towed" battalion with 3" anti-tank guns in July 1943.[1] It sailed for the United Kingdom in May 1944 aboard the Queen Elizabeth, landed at Utah Beach on 29 July 1944, and was assigned to guarding rear areas of Third Army in the Cotentin Peninsula.[2] After the breakout in August, it continued security duties, but with the start of the Ardennes Offensive in December it was moved to the front and committed to combat.[3]

Ardennes

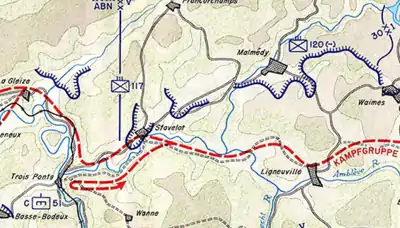

On 18 December 1944, Company A of the battalion was placed under the command of Task Force Hansen, an ad hoc force built around the 99th Infantry Battalion and the 526th Armored Infantry Battalion, both independent battalions held in First Army reserve.[4] The 99th was an unusual unit; it was composed mostly of first or second-generation Norwegian-Americans, or Norwegian nationals who had made their way to America after the occupation of Norway.[5] The task force was assigned to defend the town of Malmedy and the downstream crossings over the Amblève river at Stavelot and Trois-Ponts. Roads through Malmedy and Stavelot ran north to Spa, where the First Army headquarters were located along with large supply dumps, while roads through Trois-Ponts, and Stavelot, led westward towards the Meuse river, a strategic objective of the German advance.[6] The first platoon of Company A from the 825th, with four 3-inch anti-tank guns, was attached to Company A of the 526th and assigned to defend Stavelot, while the second and third platoons accompanied another company of the 526th to block the roads into Malmedy from the south.[7]

The German 1st SS Panzer Division had been assigned to break out to the west towards the Meuse, via Trois-Points, while the 12th SS Panzer Division was to push north over the Amblève via Malmedy.[8] The German commanders were unaware of the fuel dumps at Spa, but believed there were fuel supplies in Stavelot, making it a critical target for 1st SS Panzer.[9] The lead units of the division skirted Malmedy on 17 December and pushed towards Stavelot, but fighting in Ligneuville, along the line of march, delayed them and they did not arrive at the town until nightfall. At this point, the town was almost entirely undefended; it contained a small squad of engineers, who had laid a minefield near the bridge. However, it was filled with traffic moving westwards from the supply dumps, and this gave the impression of a strong force being present; when three German tanks probed towards the bridge and encountered the minefield, they pulled back in the belief the town was heavily defended.[10]

The 825th and the infantry they were supporting arrived that night, and took up positions around dawn on the 18th. The force was split, with half on the south bank of the river and half on the north. As the southern force was attempting to deploy, firing broke out as they met the advancing point of the 1st SS. Both 3-inch guns and their half-tracks were knocked out but some of the personnel were able to retreat across the bridge.[11][12] During the attack into the town, a gun from the 825th engaged a Tiger II heavy tank of SS Heavy Panzer Battalion 101; the shell hit the turret and did little damage, but caused the vehicle to reverse into a building in an attempt to escape. The building collapsed, trapping the tank underneath the rubble and putting it out of action.[13] The force in the town held off the attack for several hours, but eventually, around midday, was forced to retreat towards Malmedy.[14] The German force pushed through Stavelot and advanced towards Trois-Ponts; in the belief that an infantry division was following closely behind them, they left only a light guard in the town. It was attacked that evening by elements of the 30th Infantry Division, and after fighting through the night and into the next morning, was securely in American hands.[15]

On 21 December, elements of the battalion were engaged outside Malmedy, when a German force from Panzer Brigade 150 using captured American vehicles attempted to break towards the town; three tanks, two M4 Shermans and a Panzer IV, were destroyed and a number of prisoners taken. This appears to have been the last action fought by the 825th as part of Task Force Hansen.[16] Around this point, twelve men were detached to guard a signal station which linked 12th Army Group to the forces in the Ardennes. After several days operation near the enemy lines, the station was attacked and shut down on 24 December; the detachment of the 825th covered the retreat of the signallers with their equipment, successfully falling back to their own lines.[17]

Later service

From 12 to 16 January 1945, Company A of the 825th was attached to 30th Infantry Division.[18] Following this, the battalion was withdrawn from combat and assigned to rear-area security duties.[19] Whilst in the rear area, it was re-equipped with M10 GMC tank destroyers.[20]

Notes

- ↑ Nafziger, p. 3

- ↑ Letter from a man of the unit quoted in Letters from the Front, "American Voices", PBS.

- ↑ Yeide, p. 281

- ↑ Askegaard, p. 27. Askegaard gives the attached unit as B Company of the 825th; Hammons and Mitchell give it as A Company. All three are contemporary sources.

- ↑ "99th Infantry Battalion (Separate)". Archived from the original on 2 October 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ↑ Cole, pp. 259–260

- ↑ Askegaard, p. 27

- ↑ Peiper, pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Peiper, p. 8.

- ↑ Cole, pp. 264–266

- ↑ Gill (1992). p. 88.

- ↑ A photograph of the destroyed guns – still linked to the half-tracks towing them – can be seen here Archived 11 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine; an account of one of the crewmen taken prisoner is in Hammons.

- ↑ The Battle 16–18 December: Advance and Loss of Organization. A set of photographs showing the tank in situ, and the location of the gun, can be seen here.

- ↑ Cole, p. 266

- ↑ Cole, pp. 337–338. Cole notes that the attack was supported by elements of the "823rd Tank Destroyer Battalion"; this unit was operating in the area in co-operation with 30th Infantry Division, and was equipped with a mixture of three-inch guns and M10 GMC tank destroyers (Denny, p. 57). Given the similarities in name and in equipment, it is possible that some references to the 823rd confuse it for the 825th, and vice versa.

- ↑ Askegaard, pp. 27–8. Cole (pp. 359–360) describes the guns as from the 823rd (see earlier note) but as it was operating in conjunction with the 99th, it seems likely that Askegaard is correct and this was the 825th.

- ↑ "The inconspicuous radio relay Archived 21 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine", by Col. Kenneth Shiflet, in Army Communicator; see also Cole p. 425.

- ↑ 30th Infantry Division in the ETO Archived 7 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Center for Military History.

- ↑ Yeide, p. 281

- ↑ Nafziger, p. 3

References

- Yeide, Harry (2007). The tank killers: a history of America's World War II tank destroyer force. Casemate. ISBN 978-1-932033-80-9.

- Askegaard, Charles J. (2007). "99th Infantry Battalion (Separate) After Action Report, 17–31 December 1944". WWII Journal (3): 27–28. ISBN 9781576381656.

- Peiper, Joachim (2007). "1st SS Panzer Regiment (11–24 December 1944): Interview". WWII Journal (3): 6–12. ISBN 9781576381656.

- Gill, Lonnie (1992). Tank Destroyer Forces, WWII. Turner Publishing Company. ISBN 0-938021-93-1.

- Hammons, James A. (2009). "A Night in the Potato Bin". Centre de Recherches et d'Informations sur la Bataille des Ardennes. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- Cole, Hugh M. (1965). The Ardennes: Battle of the Bulge. Washington DC: US Army Center for Military History. Archived from the original on 13 November 2008. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- Nafziger, George F. (1991). "American Tank Destroyer Formations 1941–1945" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

Further reading

- Highway : A History of the 825th Tank Destroyer Battalion. Michael Sheridan, 1945.

- Mitchell, Charles A. (2002). "Action at Stavelot: 17–18 December 1944". Centre de Recherches et d'Informations sur la Bataille des Ardennes. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- Denny, Bryan E. (2003). The Evolution and Demise of U.S. Tank Destroyer Doctrine in the Second World War'. Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Army Command and General Staff College. Archived from the original on 8 April 2013.

- Tankdestroyer.net (Web based United States tank destroyer forces information resource) Tankdestroyer.net