| A Conversation with Oscar Wilde | |

|---|---|

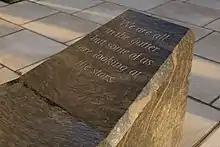

.jpg.webp) The memorial in 2019 | |

| Artist | Maggi Hambling |

| Medium | Bronze, granite |

| Subject | Oscar Wilde |

| Location | London, United Kingdom |

| 51°30′31″N 0°07′33″W / 51.50868°N 0.12589°W | |

A Conversation with Oscar Wilde is an outdoor sculpture by Maggi Hambling in central London dedicated to Oscar Wilde. Unveiled in 1998, it takes the form of a bench-like green granite sarcophagus, with a bust of Wilde emerging from the upper end, with a hand clasping a cigarette.

Creation and unveiling

The memorial was first suggested during the 1980s and early 1990s by fans of Wilde's work, including Derek Jarman. Following Jarman's death in 1994, a committee called "A Statue for Oscar Wilde" was formed to bring a tribute to fruition. The committee, led by Jeremy Isaacs, included the actors Dame Judi Dench and Sir Ian McKellen, and the poet Seamus Heaney.[1]

From sketches submitted by twelve artists, six were chosen to create maquette models of their concepts. Maggi Hambling's "witty and amusing" work was chosen for the memorial. The work is inscribed with a quotation from his play Lady Windermere's Fan: "We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars". Hundreds of individual donors and foundations contributed funds for the project.[1]

The statue is located in central London between Trafalgar Square and Charing Cross Station, behind St Martin's in the Fields church. The unveiling was on 30 November 1998. It was preceded in 1997 by an exhibition at the nearby National Portrait Gallery, bringing together drawings, models and maquettes.[2] The London sculpture was just pipped to the post by the Dublin triptych Oscar Wilde Memorial Sculpture, designed and made by Danny Osborne and unveiled in Wilde's birthplace, Merrion Square, in 1997.[3]

Reception

A Conversation with Oscar Wilde, in which Wilde is depicted laughing and smoking, caused considerable friction.[4] (The work was depicted in Smoke: a global history of smoking.)[5]

Tom Lubbock, chief art critic of The Independent,[6] while acknowledging the need for a memorial in London to Wilde, and commending the project for its "real and proper Victorian public spirit", thoroughly condemned the piece itself, in design and execution, comparing it to a Madame Tussauds waxwork.

We have nothing of the nerve, the folly, the ruin, the glory. We have nothing for history – only the whimsical notion of us chatting cheerfully with this anodyne figment.

He compared the "macaroni tangle of undulating tubey strands" to a sort of cadaver tomb called transi, part of medieval tomb sculpture depicting rotting flesh and the resulting worms, concluding that ultimately the sculpture was not about Wilde or the viewing public, but a reflection of Hambling herself.[7] Isaacs used his right of reply to point out that the sculpture "already evokes more favourable response from the public than any other statue I know in London, with the possible exception of Peter Pan".[8]

Charles Spencer, chief drama critic of The Telegraph, while professing his liking for the artist as a person, wrote how he loathed her sculptures. With respect to A Conversation, he wrote:

Hideous is too gentle a word to describe it. [...] The idea is quite witty [...] but the representation of Wilde is loathsome. He looks even worse than the picture of Dorian Gray in the attic, sporting Medusa-like snakes of hair and a vile, degenerate grin. Even Wilde, the master of the aphorism, might have been stumped for words to describe it.[9]

The sculpture was one of five works or events considered in The Resurrection of Oscar Wilde: A Cultural Afterlife, along with "the consecration of a window in Wilde's honour in Poet's Corner, Peter Tatchell's campaign for a Royal Pardon, the 1997 film Wilde [...] and the public gatherings on the centenary of his death."[10]

Both Lubbock and Spencer pointedly advised their readers not to vandalise the sculpture. However, the cigarette has been repeatedly removed by members of the public (sawn off and replaced, according to Philip Ardagh)[11] in what has been called "the most frequent act of vandalism/veneration done to a public statue in London".[12]

References

- 1 2 "London's Wilde tribute". BBC News. 30 November 1998. Archived from the original on 21 May 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ↑ Lambirth, Andrew (23 May 1997). "Wilde at heart". The Independent. Archived from the original on 18 May 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ↑ "Oscar Wilde Memorial Sculpture". Dublin City Council. Archived from the original on 16 May 2018. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ↑ Hambling, Maggi (May 2010). "Making the Waves Crash: A Conversation with Maggi Hambling". The Art Book. 17 (2): 15–17. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8357.2010.01092.x.

- ↑ Gilman, Sander L.; Xun, Zhou, eds. (2004). Smoke : A Global History of Smoking. London: Reaktion. p. 275. ISBN 978-1-86189-2-003.

- ↑ Jackson, Kevin (10 January 2011). "Tom Lubbock obituary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 18 May 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ↑ Lubbock, Tom (1 December 1998). "It's got to go". The Independent. Archived from the original on 18 May 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ↑ "Right of Reply: Jeremy Isaacs". The Independent. 3 December 1998. Archived from the original on 18 May 2018.

- ↑ Spencer, Charles (22 September 2009). "Maggi Hambling's sculptures I'd love to smash". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 25 June 2015. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ↑ "The Resurrection of Oscar Wilde: A Cultural Afterlife". The Lutterworth Press. Archived from the original on 18 May 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ↑ Ardagh, Philip (2007). Philip Ardagh's book of absolutely useless lists, absurd facts, lies, half-truths, thoughts, suggestions and musings for every day of the year. London: Macmillan Children's. p. 468. ISBN 9780230700505.

- ↑ Jenkins, Terence (2016). The Most Dangerous Woman in Europe: (And Other Londoners). p. 17. ISBN 9781785893186.

External links

- Oscar Wilde – Adelaide Street, London, UK at Waymarking.com

- Statue: Oscar Wilde reclining at LondonRemembers.com