| "A Sequel to the Yellow Millet Dream" | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Short story by Pu Songling | |||

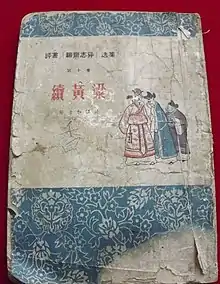

19th-century illustration from Xiangzhu liaozhai zhiyi tuyong (Liaozhai Zhiyi with commentary and illustrations; 1886) | |||

| Original title | 续黄粱 (Xu Huangliang) | ||

| Translator | Herbert Giles | ||

| Country | China | ||

| Language | Chinese | ||

| Genre(s) | Chuanqi | ||

| Publication | |||

| Published in | Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio | ||

| Publication type | Anthology | ||

| Publication date | c. 1740 | ||

| Published in English | 2008 | ||

| Chronology | |||

| |||

"A Sequel to the Yellow Millet Dream" (simplified Chinese: 续黄粱; traditional Chinese: 續黃粱; pinyin: Xù Huángliáng), also translated as "Dr Tsêng's Dream", is a short story written by Chinese author Pu Songling in Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio (1740). The story revolves around an ambitious scholar whose dreams of becoming prime minister apparently come true, and his subsequent fall from grace. Inspired by previous works of the same genre, "A Sequel to the Yellow Millet Dream" was received favourably by literary critics.

Plot

At a famous Buddhist temple in Hebei, Fujian scholar Zeng Xiaolian (曾孝廉) is patronisingly told by a geomancer that "for about twenty years, he would serve in peace and tranquility as prime minister";[1] an ego-stoked Zeng takes this to be true. Just afterwards the increasingly heavy rain forces Zeng and his fellow scholar compatriots to hole up at the monks' quarters, where Zeng discusses his potential Cabinet much to his friends' entertainment.[2]

Zeng retires to bed and is suddenly woken up by a pair of royal messengers who inform him that the Emperor requests his audience. Thereafter he is appointed prime minister, a position he abuses to his advantage by oppressing his foes and rewarding his familiars and family.[3] After the death of two of his favourite palace performers, Zeng coerces a village girl's family into selling her as a concubine.[4] Zeng's antics and arrogant personality later earn him the enmity of government officials but he is the least bothered.[4]

Academician Bao Shangshu[lower-alpha 1] writes an open letter to the palace, in which he decries Zeng's crimes and calls for his removal from office. While the Emperor gives Zeng the benefit of doubt the first time, multiple complaints by officials succeeding Bao's letter seal Zeng's doom. He is exiled to Yunnan and has his property confiscated. Palace guards take away his concubine too and Zeng is forced to flee with his wife.[5] On the run, he encounters a group of bandits who wish to punish Zeng for the wrongs he committed. Despite his protests, he is beheaded and sent to Hell, where he experiences a more intense round of torture.[6]

Zeng is sentenced to be reborn as a beggar girl who endures a bitter life of hardship, only to be sold off as a concubine to the Gu family.[7] Gu's wife, who naturally has a vendetta against her, subjects her to further abuse. One day, bandits storm into Gu's bedroom and murder him.[8] Gu's wife walks in afterwards and instantly accuses the concubine as the perpetrator; she is brutally tortured and sentenced to death by lingchi.[9]

Zeng is jolted awake and realises he is still at the monks' quarters with his friends – an observant veteran monk meditating on his bed infers what Zeng has experienced, and advises him to cultivate himself.[9] Enlightened, Zeng vows to change his materialistic and selfish ways, and disappears into the mountains.[9]

Background

Starting from the third century, early Chinese writers were already questioning the significance of their existence through creative expression, such as in the fifth-century compilation A New Account of the Tales of the World, where Liu Yiqing writes of "Yang Lin's World inside a Pillow", or Shen Chichi's Tang dynasty chuanqi "Life inside a Pillow", argued to be the most "complete form (of the genre)" prior to Pu's effort.[10]

Most notable, and one of the oldest, of the lot is the "Dream of the Yellow Millet" (黃粱夢) by Ma Zhiyuan. In Ma's work, Lü Dongbin daydreams for a perceived period of eighteen years but wakes up to discover that in actuality only a few minutes (long enough for a millet to be cooked) have passed.[11] The story's popularity has led to subsequent stories being colloquially labelled as "yellow millet" tales.[12] While Pu's fictitious narrative references Ma's writing, Nienhauser writes that it borrows more elements from "Du Zichun" (杜子春传) than it does the original "Dream of the Yellow Millet".[13]

Originally titled "Xu Huangliang" (续黄粱) and collected in Pu Songling's Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio (Liaozhai; 1740), the story was one of the first two Liaozhai entries translated by British sinologist Herbert Giles into English (alongside "The Raksha Country and the Sea Market") prior to the publication of Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio in 1880.[14] Giles titled the story "Dr Tsêng's Dream".[15] Subsequent translators of the story have included Sidney L. Sondergard, who included "A Sequel to the Yellow Millet Dream" in Strange Tales from Liaozhai (2008).[16]

Themes

The central theme of "A Sequel to the Yellow Millet Dream" is materialism, with the emboldened message of "moral conscience over the consciousness of the transience of human life";[10] Chang and Chang (1998) posit that the dream experienced by Zeng is a metaphor for the impermanence of life.[10] The original "ethos (of the Yellow Millet Dream)" is not conveyed in Pu's story, however he does refer to it in an appended statement to criticise "the universality of humanity's ruthless and foolish quest for fame and success".[10]

Reception

Chun-shu Chang and Shelley Hsueh-lun Chang highlight Pu's breaking away from convention, in that "A Sequel to the Yellow Millet Dream" is not a "simple allegory (of life)", comparing it to similar works by preceding writers which they deem as "one-dimensional" with "no intellectual signpost or imagery" and "unsophisticated plots and simple narratives".[10] By contrast, Pu "(goes beyond) the basic story plot and themes set down by Chen Shi-shi" and "enlarges the plot" by adding tiers to the protagonist's dream.[10] Likewise, Mei-Kao Kow lauds Pu for expanding upon his predecessors' efforts, while pointing out the story's similarity to a story from Taiping Guangji.[17] Sondergard describes the story as a demonstration of Pu's contempt for "unworthy" pseudo-scholars like the "smug" Zeng.[16]

See also

References

Notes

Citations

- ↑ Sondergard 2008, p. 710.

- ↑ Sondergard 2008, p. 712.

- ↑ Sondergard 2008, p. 713.

- 1 2 3 Sondergard 2008, p. 714.

- ↑ Sondergard 2008, p. 717.

- ↑ Sondergard 2008, p. 718.

- ↑ Sondergard 2008, p. 719.

- ↑ Sondergard 2008, p. 721.

- 1 2 3 Sondergard 2008, p. 722.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Chang & Chang 1998, p. 175.

- ↑ Katz 1999, p. 184.

- ↑ Katz 1999, p. 185.

- ↑ Nienhauser 2010, p. 66.

- ↑ Wang 2017, p. 62.

- ↑ Giles 1880, p. 387.

- 1 2 Sondergard 2008, p. 7.

- ↑ Kow 2009, p. 91.

Bibliography

- Chang, Chun-shu; Chang, Shelley Hsueh-lun (1998). Redefining History: Ghosts, Spirits, and Human Society in Pʻu Sung-ling's World, 1640–1715. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-10822-0.

- Giles, Herbert A. (1880). Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio. London: Thos de la Rue & Co.

- Katz, Paul R. (1999). Images of the Immortal: The Cult of Lü Dongbin at the Palace of Eternal Joy. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2170-8.

- Kow, Mei-Kao (2009). 明清小说与中国文化丛论: 辜美高卷 [A discussion of Ming and Qing dynasty tales and Chinese culture] (in Chinese). Singapore Youth Publications. ISBN 978-981-08-3329-9.

- Nienhauser, William H. (2010). Tang Dynasty Tales: A Guided Reader. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-4287-28-9.

- Sondergard, Sidney (2008). Strange Tales from Liaozhai. Jain Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-89581-051-9.

- Wang, Shengyu (August 2017). Chinese Enchantment: Reinventing Pu Songling's Classical Tales in the Realm of World Literature (PhD thesis). University of Chicago.