Abbott districts are school districts in New Jersey that are provided remedies to ensure that their students receive public education in accordance with the state constitution. They were created in 1985 as a result of the first ruling of Abbott v. Burke, a case filed by the Education Law Center. The ruling asserted that public primary and secondary education in poor communities throughout the state was unconstitutionally substandard.[1] The Abbott II ruling in 1990 had the most far-reaching effects, ordering the state to fund the (then) 28 Abbott districts at the average level of the state's wealthiest districts. The Abbott District system was replaced in 2007 by the New Jersey Schools Development Authority.

There are now 31 "Abbott districts" in the state, which are now referred to as "SDA Districts" based on the requirement for the state to cover all costs for school building and renovation projects in these districts under the supervision of the New Jersey Schools Development Authority.[2] The term "Abbott district" is still in common use since the Abbott districts receive very high funding levels for K-12 and are the only districts in New Jersey where the state pays for Pre-K for all students.

Since the original ruling in 1985, New Jersey increased spending such that Abbott district students received 22% more per pupil (at $20,859) vs. non-Abbott districts (at $17,051) in 2011.[3] 60% of New Jersey's education aid goes to the Abbotts.[4]

One evaluation concluded that the effect on academic achievement in Abbott districts was greater in lower grades and declined in subsequent grades, until there was no effect in high school. The achievement gap in math test scores for fourth graders narrowed from 31 points in 1999 to 19 points in 2007, and on reading tests from 22 points in 2001 to 15 points in 2007. The gap in eighth grade math narrowed less, from 30 points in 2000 to 26 points in 2008, and did not change in reading. The gap did not narrow in high school.[5] In addition, a 2012 study by the New Jersey Department of Education determined that score gains in the Abbotts were no higher than score gains in high-poverty districts that did not participate in the Abbott lawsuit and therefore received much less state money.[6]

History

Abbott districts are school districts in New Jersey covered by a series of New Jersey Supreme Court rulings, begun in 1985,[7] that found that the education provided to school children in poor communities was inadequate and unconstitutional and mandated that state funding for these districts be equal to that spent in the wealthiest districts in the state.

The Court in Abbott II[8] and in subsequent rulings,[9] ordered the State to assure that these children receive an adequate education through implementation of certain reforms, including standards-based education supported by parity funding. It include various supplemental programs and school facilities improvements, including to Head Start and early education programs. The Head Start and NAACP were represented by Maxim Thorne as amici curiae in the case.[10]

The part of the state constitution that is the basis of the Abbott decisions requires that:

[t]he Legislature shall provide for the maintenance and support of a thorough and efficient system of free public schools for the instruction of all the children in the State between the ages of five and eighteen years.[11]

The Abbott designation was formally eliminated in the School Funding Reform Act of 2008, but the designation and special aid were restored in 2011 when the NJ Supreme Court blocked the Christie administration from making any aid cuts to the Abbott districts while allowing cuts to other districts.[12]

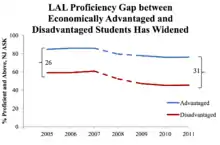

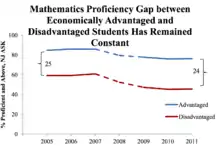

There is limited evidence that the legal actions have improved student learning outcomes in the Abbott districts.[13] Instead, despite 40 years of increased funding, the gaps between Abbott Schools and the suburban counterparts has widened significantly.[6]

Criteria

The Court in the Abbott II ruling of 1990 explicitly limited the Abbott programs and reforms to a class of school districts identified as "poorer urban districts" or "special needs districts." In 1997, these districts became known as "Abbott districts." The Court identified the specific factors used to designate districts as "Abbott districts." These districts:

- must be those with the lowest socio-economic status, thus assigned to the lowest categories on the New Jersey Department of Education's District Factor Groups (DFG) scale;

- "evidence of substantive failure of thorough and efficient education;" including "failure to achieve what the DOE considers passing levels of performance on the High School Proficiency Assessment (HSPA);"

- have a large percentage of disadvantaged students who need "an education beyond the norm;"

- existence of an "excessive tax [for] municipal services" in the locality where the district is located.[14]

Using these factors, the Court in Abbott II identified 28 districts as Abbott districts. The Court also gave the New Jersey Legislature or the Commissioner of Education the authority to classify additional districts as Abbott districts based on these factors, which would then entitle the children to the Abbott programs and reforms. In 1998, the legislature classified 3 additional districts, bringing the 2009 total of Abbott districts to 31.

Since the 1990s no district has been removed from the Abbott list. Hoboken remains on the list despite its gentrification.

Performance

The program improved achievement in early grades, but not in upper grades. Early education programs including free preschool helped close part of the gaps for Fourth graders whose performance gap "narrowed from 31 points in 1999 to 19 points in 2007, and on state reading tests from 22 points in 2001 to 15 points in 2007."[5] However, as students advanced in grade, their relative performance gains were lost, such that high school students showed no improvement at all and one expert, the Assistant Commissioner at the New Jersey Department of Education from 2002 to 2007 said that the program had not eliminated the effects of poverty. "When you get to middle school, eighth grade, high school – forget about it. This has been a huge failure."[5]

A 2012 New Jersey Department of Education study notes that between 1973 (the time of the legal decision) and 2010 the average per-pupil expenditure in those districts had nearly tripled to $18,850, or $3,200 more than the State average (excluding the former-Abbotts) and $3,100 more than the State's wealthiest districts. In total, more than $40B in additional funding has been provided to the schools. Despite "more than adequate" funding, the achievement gap between economically advantaged and disadvantaged students persists or has widened.[6]

When measuring college readiness, Abbott districts fare poorly relative to other areas despite higher than average spending per pupil. During the 2011-2012 school year:

- Newark spent approximately $17,553 per-pupil, but only 9.8% of its SAT test takers met the College-Readiness Benchmark in 2009-2010.

- Camden spent approximately $19,204 per-pupil, but only 1.4% of its test takers met the Benchmark.

- Asbury Park spent $23,940 per-pupil but none of its SAT test takers in 2009-2010 met the Benchmark.

In 2011, there was a 38% gap between white and African American students on college readiness, up from 35% in 2006. The gap for Hispanic students rose from 28% to 30% in the same period.[6]

Public opinion

In 2008, a Fairleigh Dickinson University PublicMind poll surveyed New Jersey residents about their awareness of and attitudes towards the Abbott decisions; 57% of voters reported that they had heard or read "nothing at all" about the Abbott decisions. Only 12% of voters responded that they had read or heard "a great deal" about the Abbott decisions.[15] The survey also found that, despite a seeming lack of knowledge about the Abbott decisions, voters in New Jersey largely approved of the court decisions with 55% of the public approving and 28% disapproving.[15] Dr. Peter Woolley, Executive Director of the PublicMind Poll, explained the results by stating, "voters don't know the details but they agree with the principles."[15]

Districts

The following 31 school districts were currently identified as Abbott districts:[16]

- Asbury Park Public Schools (Asbury Park)

- Bridgeton Public Schools (Bridgeton)

- City of Burlington Public School District (Burlington City)

- Camden City Public Schools (Camden)

- East Orange School District (East Orange)

- Elizabeth Public Schools (Elizabeth)

- Garfield Public Schools (Garfield)

- Gloucester City Public Schools (Gloucester City)

- Harrison Public Schools (Harrison)

- Hoboken Public Schools (Hoboken)

- Irvington Public Schools (Irvington)

- Jersey City Public Schools (Jersey City)

- Keansburg School District (Keansburg)

- Long Branch Public Schools (Long Branch)

- Millville Public Schools (Millville)

- Neptune Township Schools (Neptune Township)

- New Brunswick Public Schools (New Brunswick)

- Newark Public Schools (Newark)

- Orange Board of Education (Orange)

- Passaic City School District (Passaic)

- Paterson Public Schools (Paterson)

- Pemberton Township School District (Pemberton Township)

- Perth Amboy Public Schools (Perth Amboy)

- Phillipsburg School District (K-12 from Phillipsburg, 9-12 from Alpha, Bloomsbury (in Hunterdon County), Greenwich Township, Lopatcong Township and Pohatcong Township)

- Plainfield Public School District (Plainfield)

- Pleasantville Public Schools (K-12 from Pleasantville, 9-12 from Absecon)

- Salem City School District (Salem, New Jersey)

- Trenton Public Schools (Trenton)

- Union City School District (Union City)

- Vineland Public Schools (Vineland)

- West New York School District (West New York)

See also

- San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 1 (1973), a U.S. Supreme Court case that held that a school-financing system based on local property taxes was not an unconstitutional violation of the Fourteenth Amendment's equal protection clause.

- Gannon v. Kansas, also known as Gannon v. State, a similar school funding lawsuit.

- The Mount Laurel doctrine, a series of New Jersey Supreme Court cases requiring municipalities to provide affordable housing.

- Latino Action Network v. New Jersey, a school desegregation lawsuit filed in 2018

- Serrano v. Priest (California)

References

- ↑ "The History of Abbott v. Burke". Archived from the original on October 18, 2012. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- ↑ "What are SDA Districts?". New Jersey Schools Development Authority. Archived from the original on May 2, 2012. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

SDA Districts are 31 special-needs school districts throughout New Jersey. The districts were renamed after the elimination of the Abbott designation through passage of the state's new School Funding Formula in January 2008.

- ↑ "New Taxpayers' Guide to Education Spending Provides, for the First Time, Complete Total Per-Pupil Cost; Outlines Actual Cost of Educating Students for Greater Accountability". State of New Jersey Department of Education. May 20, 2011. Archived from the original on December 4, 2011. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- ↑ Wichert, Bill (December 1, 2011). "Chris Christie claims 31 former Abbott districts receive 70 percent of the state aid". PolitiFact New Jersey. Archived from the original on July 20, 2015. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- 1 2 3 "New Jersey's Decades-Long School Finance Case: So, What's the Payoff?". Teachers College of Columbia University. November 19, 2009. Archived from the original on August 9, 2014. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cerf, Christopher C. (February 23, 2012). "Education Funding Report" (PDF). Nj.gov. New Jersey Department of Education. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 1, 2015. Retrieved December 21, 2015.

- ↑ Abbott v. Burke, 100 N.J. 269, 495 A.2d 376 (1985) ("Abbott I").

- ↑ Abbott v. Burke, 119 N.J. 287, 575 A.2d 359 (1990) ("Abbott II").

- ↑ Abbott v. Burke, 136 N.J. 444, 643 A.2d 575 (1994) (Abbott III); Abbott v. Burke, 149 N.J. 145, 693 A.2d 417 (1997) (Abbott IV).

- ↑ "Abbott VIII" (PDF). Education Law Center. 2015. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ↑ N.J. Const. art. VIII, § 4, P 1.

- ↑ Megerian, Chris (May 24, 2011). "Christie says he won't fight N.J. Supreme Court order to add $500M in funding for poor school districts". The Star-Ledger. Archived from the original on May 27, 2011. Retrieved May 25, 2011.

- ↑ See the opposing views in Hanushek, Eric A., and Alfred A. Lindseth. 2009. Schoolhouses, courthouses, and statehouses: Solving the funding-achievement puzzle in America's public schools. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, and in Goertz, Margaret E., and Michael Weiss. 2007. "Money Order in the Court: The Promise and Pitfalls of Redistributing Educational Dollars through Court Mandates: The Case of New Jersey." In Annual Meeting of the American Education Finance Association. Baltimore, MD.

- ↑ Abbott II, 119 N.J. at 342.

- 1 2 3 Fairleigh Dickinson University's PublicMind Poll "Voters Unfamiliar with Abbott and Mount Laurel" Archived 2011-06-29 at the Wayback Machine press release (June 25, 2008)

- ↑ Abbott School Districts Archived 2016-10-07 at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Education. Accessed June 15, 2016.