Abd al-Malik ibn Umar ibn Marwan ibn al-Hakam (Arabic: عبد الملك ابن عمر بن مروان بن الحكم, romanized: ʿAbd al-Malik ibn ʿUmar ibn Marwān ibn al-Ḥakam; c. 718– c. 778), also known as al-Marwani, was an Umayyad prince, general and governor of Seville under the first Umayyad emir of al-Andalus (Islamic Spain), Abd al-Rahman I (r. 756–788). He led two major campaigns in 758 and 774, the first against the previous ruler of al-Andalus Yusuf ibn Abd al-Rahman al-Fihri and the second against the rebellious troops of Seville and Beja. His victories solidified the Umayyad emirate's control of western al-Andalus. His descendants continued to play important political and military roles in the Emirate well into the 10th century.

Ancestry

Abd al-Malik ibn Umar was born c. 718.[1] He was a grandson of the Umayyad caliph Marwan I (r. 684–685). His father Umar was the caliph's only son by Zaynab bint Umar. She was a paternal granddaughter of Abu Salama from the prominent Banu Makhzum clan of the Quraysh tribe and a daughter of the Islamic prophet Muhammad's stepson.[2]

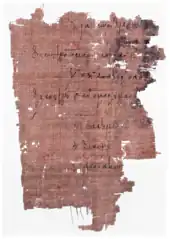

Umar resided in Fustat, the capital of Egypt, a province of the Syria-centred caliphate. His house there was bestowed on him by his half-brother, the governor of Egypt Abd al-Aziz ibn Marwan (r. 685–705).[3] The 'Umar ibn Marwan' mentioned in two Greek papyri from Egypt may be identified with Abd al-Malik's father.[4] Abd al-Malik was initially established in Egypt.[5]

Career

When the Umayyad Caliphate was toppled by the Abbasids in 750 they carried out mass executions of the Umayyad dynasty in Syria, Iraq, Egypt and Arabia. Several, mostly less eminent Umayyads, including Abd al-Malik, escaped to al-Andalus (Islamic Spain).[6] The early Islamic sources hold that he left Egypt and arrived in al-Andalus in 757 or 758. However, modern historian Alejandro García Sanjuán, considers that Abd al-Malik most likely arrived in 754 or 755.[1] He was accompanied by his cousin Juzayy ibn Abd al-Aziz ibn Marwan (d. 757) and their respective children.[7] His distant Umayyad kinsman, a great-great-grandson of Marwan I Abd al-Rahman I,[1] established himself on the peninsula in 755–756 with the support of local Umayyad mawali (non-Arab Muslim freedmen or clients) and friendly Syrian troops in the region and proclaimed himself emir (governor or ruler) in Cordoba.[8] Abd al-Malik was the eldest of the Marwanids in al-Andalus.[1] He is generally credited with counselling Abd al-Rahman to drop the name of the Abbasid caliph al-Mansur (r. 754–775) from the Friday prayer—a traditional acknowledgement of Islamic sovereignty—in 757.[9]

Abd al-Malik gained the confidence of Abd al-Rahman. He became one of the Emir's top generals and a strongman of the nascent Umayyad emirate as it expanded its control over the chiefs of the practically autonomous Arab junds (armies or garrisons) and older-established elites across al-Andalus.[1][9] To assert his authority over the junds of Egypt and Homs based in Beja and Seville, respectively, Abd al-Rahman appointed Abd al-Malik the governor of Seville and the western part of the Iberian Peninsula,[10] and his son, Abd Allah, the governor of Morón.[1] Although permanent command of the Emir's army was given to his two mawali Badr and Abu Uthman Ubayd Allah ibn Uthman, Abd al-Malik was given command of expeditions in 758 and 774.[11] In the first campaign, Abd al-Malik mobilized the jund of Homs and subdued an attempt by the previous ruler of al-Andalus, the Qurayshite emir Yusuf ibn Abd al-Rahman al-Fihri, to regain power.[1]

Abd al-Malik had been replaced by a leader of the Seville jund, Abu al-Sabbah al-Yahsubi, but the latter rebelled against Abd al-Rahman and was dismissed from his post.[5] Abd al-Malik was the only member of Abd al-Rahman's court to advocate for Abu al-Sabbah's execution,[12] reportedly telling the Emir:

Don't let him get away: for he will bring us calamity

Take a firm hand and rid yourself of this sickness.[13]

Abd al-Rahman apparently informed his court that he had already had Abu al-Sabbah executed.[13] The historian Eduardo Manzala Moreno connects this episode to a probable rivalry between Abd al-Malik and his family and Abu al-Sabbah for control of Seville and the jund of Homs.[5] Moreno holds that the ambitions of Abd al-Malik and his family was likely the main cause for the disaffection of the junds in Seville and Beja.[14] In the campaign of 774, Abd al-Malik decisively defeated a wide-scale revolt by the junds, which were led by Abu al-Sabbah's cousins and supporters and who attempted a surprise capture of Cordoba.[15][14] During the campaign, Abd al-Malik ordered the execution of his own son Umayya, the commander of his vanguard, for retreating before the rebels in battle.[1][14] Abd al-Malik's victory sealed the submission of western al-Andalus to the Umayyad emirate.[16] Abd al-Rahman's confidence in Abd al-Malik was also strengthened by the marriage of Abd al-Rahman's son and chosen successor Hisham I (r. 788–796) to Abd al-Malik's daughter Kanza.[1]

Death and legacy

Abd al-Malik died in c. 778.[1] His decisive victories on behalf of Abd al-Rahman were key to the establishment of the Umayyad emirate in al-Andalus.[17] His sons Abd Allah, Ibrahim and al-Hakam all served as viziers of Abd al-Rahman.[1] Abd al-Malik left numerous descendants recorded by the sources, including several who served as viziers or quwwad (army leaders).[18] A branch of the family settled in Seville and the western areas of the peninsula.[14] As Umayyads, members of Abd al-Malik's family viewed themselves as equals to the ruling emirs in Cordoba.[17]

Abd al-Malik's grandson al-Abbas ibn Abd Allah served as the governor of Beja under Hisham I.[14][19] Another descendant, Ahmad ibn al-Bara ibn Malik ibn Abd Allah, was appointed governor of Zaragoza by Emir al-Mundhir (r. 886–888), but was suspected of disloyalty and assassinated by order of al-Mundhir's successor Abd Allah (r. 888–912).[17][20] The wider family in Seville joined the rebellion against Abd Allah but relocated to Cordoba when the troops of Seville surrendered to Emir Abd al-Rahman III in 913.[17] Thereafter, several served as governors, generals and viziers.[17] Another of Abd al-Malik's descendants, Ahmad ibn Ishaq al-Qurashi,[lower-alpha 1] was a pretender to the Umayyad Caliphate in al-Andalus in the 10th century.[18][22]

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Sanjuán, Alejandro García. "Abd al-Malik b. 'Umar b. Marwan". Diccionario biográfico español (DB~e) (in Spanish). Madrid: Real Academia de la Historia. Archived from the original on 30 January 2022. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ↑ Ahmed 2010, p. 90.

- ↑ Hilloowala 1998, p. 208.

- ↑ Morelli 1998, pp. 220–221.

- 1 2 3 Moreno 1998, p. 102.

- ↑ Kennedy 1996, pp. 30–32.

- ↑ James 2012, p. 97.

- ↑ Kennedy 1996, p. 31.

- 1 2 Kennedy 1996, p. 32.

- ↑ Kennedy 1996, p. 35.

- ↑ Hernández 1998, p. 68.

- ↑ Moreno 1998, pp. 102–103.

- 1 2 James 2012, p. 104.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Moreno 1998, p. 103.

- ↑ Kennedy 1996, pp. 35–36.

- ↑ Kennedy 1996, p. 36.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fierro 2011, p. 109.

- 1 2 Moreno 1998, p. 103, note 48.

- ↑ Castro 2010, p. 199.

- ↑ Kennedy 1996, pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Uzquiza Bartolomé 1994, p. 460.

- ↑ Moreno 1991, p. 356.

Bibliography

- Ahmed, Asad Q. (2010). The Religious Elite of the Early Islamic Ḥijāz: Five Prosopographical Case Studies. Oxford: University of Oxford Linacre College Unit for Prosopographical Research. ISBN 978-1-900934-13-8.

- Castro, Antonio Arjona (2010). Historia de Córdoba en el califato omeya (in Spanish). Córdoba: Almuzara. ISBN 978-84-929-24-17-2.

- Fierro, Maribel (2011). "The Battle of the Ditch (al-Khandaq) of the Cordoban Caliph ʿAbd al-Raḥmān III". In Ahmed, Asad Q.; Sadeghi, Benham; Bonner, Michael (eds.). The Islamic Scholarly Tradition: Studies in History, Law, and Thought in Honour of Professor Michael Allen Cook. Leiden and Boston: Brill. pp. 107–130. ISBN 978-90-04-19435-9.

- Hernández, Miguel Cruz (1998). "The Social Structure of al-Andalus during the Muslim Occupation (711–755) and the Founding of the Umayyad Monarchy". In Marin, Manuela (ed.). The Formation of al-Andalus, Part 1: History and Society. New York: Ashgate Publishing. pp. 51–84. ISBN 978-0-86078-708-2.

- Hilloowala, Yasmin (1998). The History of the Conquest of Egypt, being a Partial Translation of Ibn 'Abd al-Hakam's Futuh Misr and an Analysis of this Translation (PDF) (Thesis). The University of Arizona.

- James, David (2012). A History of Early Al-Andalus: The Akhbar Majmu'a. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-66943-6.

- Kennedy, Hugh (1996). Muslim Spain and Portugal: A Political History of al-Andalus (First ed.). London: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-0-582-49515-9.

- Morelli, Federico (1998). "P. Vindob. G 42920 e la φιλοτιμία di 'Umar b. Marwán". Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik (in Italian). 121: 219–221. JSTOR 20190217.

- Moreno, Eduardo Manzano (1991). La frontera de al-Andalus en época de los Omeyas. Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. ISBN 9788400071950.

- Moreno, Eduardo Manzano (1998). "The Settlement and Organisation of the Syrian Junds in al-Andalus". In Marin, Manuela (ed.). The Formation of al-Andalus, Part 1: History and Society. New York: Ashgate Publishing. pp. 85–114. ISBN 978-0-86078-708-2.

- Uzquiza Bartolomé, Aránzazu (1994). "Otros Linajes Omeyas en al-Andalus". In Marín, Manuela (ed.). Estudios onomástico-biográficos de Al-Andalus: V (in Spanish). Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. pp. 445–462. ISBN 84-00-07415-7.