Abdelghani Bousta | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | February 18, 1949 |

| Died | September 21, 1998 (aged 49) |

| Nationality | Moroccan |

| Occupation | Politician |

Abdelghani Bousta (18 February 1949 – 21 September 1998), was a Moroccan politician who opposed the monarchical power of his country. Like many of his fellow fighters at the time, his democratic views in favour of the separation of powers and taking absolute power away from King Hassan II forced him into exile for over twenty years.

He often quoted Max Frich, who once said: "he who fights might lose; he who gives up the fight has already lost".

1949-1969: birth and studies

Bousta was born on 18 February 1949 in Marrakesh. In 1957, after Morocco gained independence, he gave his first speech, with the support of his school. In his speech, he expressed how urgent it was for all Moroccans to be involved in the construction of a freed and free Moroccan and how the whole country should get together to do so.

In 1965, aged 16, he passed his scientific baccalauréat. He then went on to study at the École Mohammadia d'ingénieurs (EMI) in Rabat. During that time, he took part in student protest movements and in university strikes. He became an electronics engineer at the age of 20.

He then went to Grenoble in France to study for a postgraduate certificate (DEA), specialising in industrial system controls at the Institut Polytechnique de Grenoble (IPG).

1969-1973: politics

When he arrived in Grenoble, he joined the National Union of Popular Forces (Union nationale des forces populaires - UNFP) and was very active in the party and in the National Union of Moroccan students (Union nationale des étudiants du Maroc - UNEM).

In 1971, he joined the trend that chose to fight with weapons, which was led by Mohamed Basri (also known as le Fquih).

Once he had gained his degree in industrial control systems, and defended his thesis, he returned to Morocco in 1972 where he became the head of dams for South Morocco.

1973: 3 March and life in hiding

The March 1973 events, which were mainly organised by Mohamed Basri, forced him into hiding and then exile. At the beginning of 1973, after the two military coups in 1971 and 1972, there was a period of armed actions against national establishments in some towns and countries in Morocco.

At the beginning of March 1973, some UNFP activists crossed the border between Algeria and Morocco and reach the Atlas to carry out substantial armed action against the Moroccan regime. They were surrounded on 3 March 1973 by the police. Several of them, including Mahmoud Bennouna, Assekour Mohamed and Brahim Tizniti, were killed. Other activists risked their lives trying to reach Algeria.

After the events, many activists were arrested and eight were sentenced to death and executed on 1 November 1973, the day of Eid al-Adha. They were: Omar Dahkoun, Abdellah Ben Mohamed, Aît Lahcen, Barou M'Barek, Bouchakouk Mohamed, Hassan Idrissi, Moha Nait Berri and Taghjite Lahcen.

From May 1973 to September 1974, Abdelghani Bousta lived in hiding. During this time, he realised the mistakes made when the March 1973 events were organised. In 1975, he wrote a critical analysis of UNFP on behalf of the Option Révolutionnaire (Revolutionary option) movement, harshly criticising the events and the leaders: “[…] the March 1973 events helped shed light on the internal contradictions of the Party and show the true nature of its leaders: putschist and adventurous leaders who did not see any problem in sacrificing dozens of activists in a hazardous battle.”

1974-1994: exile in Paris

Abdelghani chose to go into exile in Paris in September 1974.

After the founding congress of the Socialist union of popular forces (Union socialiste des forces populaires) in 1975, he considered that the Party leaders were taking a step backwards: he believed that they were not simply changing the name of the party (USPF instead of UNFP) but more importantly giving up fundamental principles. With a number of other activists, he decided to found a school of thought as a political alternative, which criticised populist and putschist decisions and activities on the one hand and opportunistic and reformist trends on the other.

1975-1983: the Option révolutionnaire movement

On 1 May 1975, the El Ikhtiar Attaouri (revolutionary option) movement was founded, mainly instigated by Abdelghani. In 1976, he started a monthly magazine with the same name. The many articles he wrote helped train many activists, including some political prisoners. He coordinated the movement's activities and played an active part in determining its leanings, its activities, and its different positions, in the monthly magazine and in several brochures (e.g. the Sahara issue, critical analysis of the Mouvement de Libération Nationale (National liberation movement) and UNFP).

In 1977 he co-founded the Trois Continents association, which welcomed many Arab activists (Syrians, Algerians, Palestinians...). They published the first issue of a magazine in support of the Third-World, which aimed at being in line with the revolutionary views of Mehdi Ben Barka. Unfortunately, as early as the first issue, the magazine could not be published because its financing had to be withdrawn.

He then founded the Centre Averroès (Ibn Ruchd) and supervised the translation of several books into Arabic: The commander of the faithful by J. Watherbury, Le fellah marocain, détenteur du trône by Rémi Leveau, Maroc, Impérialisme et Immigration by A. Baroudi.

The Option révolutionnaire movement spread abroad, not only to the Netherlands, Belgium, Spain, Italy, Germany and France but also to Libya and Algeria. The encounters led to ideological and political debates. Action programmes were set up to criticise the Moroccan regime and Moroccan politics, and develop activist links with the different left-wing Moroccan trends. At the same time, it became more and more obvious that he and Mohamed Basri were starting to disagree.

On 30 March 1982, the Option révolutionnaire movement publicly declared that any national and international political declarations made by Mohamed Basri did not express the views of the movement. As Mohamed Basri kept on making such declarations, the movement released a statement on 2 February 1983 clearly saying that they were breaking off their relationship with him.

In 1983, the Alikhtiar Attaouri magazine wrote: ‘The Option Révolutionnaire movement has always fought the reformist-adventurous trend of the Party. […] It has always considered that reformism and adventurism are intertwined”.

1984: dissolution of the Option révolutionnaire movement

In 1983 most of the activists of the national administrative commission of the Union socialiste des forces populaires (USFP-CAN, which later became PADS) voted against the party executives and broke off from them. According to them, the party executives were making compromising decisions which went against the fundamental principles of the party.

Abdelghani Bousta then suggested dissolving the Option Révolutionnaire movement, which meant that many activists joined USPF-CAN, which he represented abroad.

1989: founding of the Centre marocain pour la coopération et les droits de l'homme (Moroccan centre for cooperation and human rights)

In 1986 he founded Alwatane (the Nation) magazine, which dealt with the topics of liberation, development and socialism in Morocco and other Arab countries.

The development of cooperation and friendship relationships with the international progressive movement, particularly in Europe, led him to create the Centre marocain pour la coopération et les droits de l'homme (CMCDH) with other fellow activists.

1993: founding congress of PADS

In 1993 the founding congress of PADS (Parti de l'Avant-garde démocratique socialiste – Socialist democratic avant-garde party), formerly the USFP-CAN, took place; exiled activists were able to take part over the phone.

On this occasion, Abdelghani Bousta made a speech to the PADS congress on behalf of the exiled activists, in which he said: “Though we are far apart and circumstances separate us today, be assured that we are with you. […] We are experiencing this historical moment and this great change of direction in the splendid development of our Party. This change of direction shows that our party is firmly rooted in its elaborate fundamental principles, which have been developed and fine-tuned by generations of sincere activists. […] Our people has fought many battled and uprisings, shed many tears and drops of blood to see our aims and aspirations triumph.”

From this date on, he was the PADS representative for foreign affairs in his capacity as a member of the national executive board and the central committee. He spread the views of his party by creating the magazine La lettre du Maroc, the organ of the PADS abroad, in September 1993. He took part in many congresses in France, Spain, Portugal... and chaired conferences and workshops about human rights and the political situation in Morocco.

1994: Return from exile and creation of Droits pluriels

Following the general amnesty in 1994, and after much hesitation, he decided to return to Morocco from time to time, so as to help his comrades develop and strengthen the ideological, political, economic and strategic aspects of the Party.

He regularly took part in central committee meetings and made concrete suggestions about action programmes, wrote analytical articles in the Party newspaper (Attarik), giving a critical history of the national movement and the UNFP, and writing about the principles and foundations of the constitution of a united democratic front.

In October 1995 he wrote an explicit internal memorandum in which he resigned from the national board of PADS, whilst still remaining a member of the central committee.

From then on, his main concern was to write a political history of Morocco and of the Moroccan political movement, and UNFP in particular. At the same time, he and his family worked on gathering all the texts written by Ben Barka. By analysing the politics of Ben Barka, he wanted to give a clear analysis of present politics. Furthermore, being deeply committed, he intended to take part in the next congress of his party in 1999, by making ideological and political contributions.

In July 1996, he was diagnosed with a form of cancer which was particularly advanced for his age (47), but which was maybe brought on by the vicissitudes of exile, disillusion and deep deception. Despite his illness, for more than two years, he started writing texts which were to remain unfinished, and he often helped write, publish and broadcast Droits pluriels; he also took part in conferences and workshops.

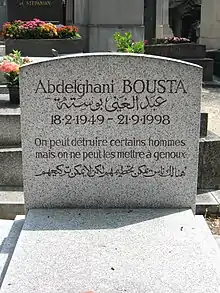

He died on 21 September 1998, and was buried at Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. He wished to experience the year 2000 with new technology, and created a website about Morocco and human rights, which he called Maroc-Réalités.[1] One of the main aims of the site was to gather texts written by martyrs and democrats, especially Mehdi Ben Barka. He simply could not imagine that no voice would remain to speak out against injustice, and hoped that one day, the future would be brighter.

Notes

Free text taken from Maroc Réalités - Abdelghani Bousta - English Biography [2]