The history of abolitionism in Brazil goes back to the first attempt to abolish indigenous slavery in Brazil, in 1611, to its definitive abolition by the Marquis of Pombal, in 1755 and 1758, during the reign of King Joseph I, and to the emancipation movements in the colonial period, particularly the 1798 Bahian Conspiracy, whose plans included the eradication of slavery. After the Independence of Brazil (1822), the discussions on this subject extended throughout the Empire period, acquiring relevance from 1850 onwards and a truly popular character from 1870 onwards, culminating with the signing of the Golden Law on May 13, 1888, which abolished slavery in Brazil.

Imperial period

José Bonifácio de Andrada e Silva, in his famous representation to the Constituent Assembly of 1823,[1] had already called slavery a "deadly cancer that threatened the foundations of the nation".

Councilor Antônio Rodrigues Veloso de Oliveira was one of the first abolitionist voices in newly independent Brazil. In the words of historian Antônio Barreto do Amaral: "In his 'Memórias para o melhoramento da Província de São Paulo, aplicável em grande parte às demais províncias do Brasil' (Memoirs for the improvement of the São Paulo Province, applicable in large part to the other provinces of Brazil), presented to Prince João VI in 1810, and published by the author in 1822, after enumerating and criticizing the acts of the Captains Generals that contributed to hindering the development of São Paulo, he went on to deal with the servile element and free immigration, which could contribute to the coming of European populations plagued by the ravages of Napoleon's wars. Councilor Veloso de Oliveira proposed that in the impossibility of establishing migratory currents, the slave trade should continue. However, he also proposed that the slavery of imported individuals should be restricted to ten years and that slaves' children in Brazil should be born free."[2]

During the Regency Period, since November 7, 1831, the Chamber of Deputies had approved and the Regency had promulgated the Feijó Law, which prohibited the trafficking of African slaves into the country, but this law was not enforced.

In March 1845, the term of the last treaty signed between Brazil and the United Kingdom expired, and the British government decreed, in August, the Aberdeen Act. Named after Lord Aberdeen of the Foreign Office, the act gave the British Admiralty the right to arrest slave ships, even in Brazilian territorial waters, and to judge their captains. Through the act, British captains were empowered to moor Brazilian ships on the high seas and check whether they were carrying slaves. If they did, they had to dispose of the cargo, returning the slaves to Africa, or transferring it to British ships.

Criticized in the United Kingdom itself for pretending to make England the "moral guardian of the world," in Brazil, the Aberdeen Act provoked panic in slave traders and landowners. The immediate consequence of the act was the significant and paradoxical increase in the slave trade, due to the anticipation of slave purchases before the definitive prohibition and, especially, the great increase in the price of slaves. Caio Prado Júnior says that in 1846, 50,324 slaves entered Brazil, and in 1848, 60,000. It is estimated that until 1850, the country received 3.5 million African captives.

British ships chased suspicious vessels, while the British navy invaded territorial waters and threatened to block ports. There were incidents, exchanges of fire in Paraná. Some captains, before being boarded, threw their human cargo into the ocean. They were farmers or landowners, all slaveholders.

The provinces protested, because at that time in Brazil, slavery was something natural, integrated into the routine and customs, seen as a necessary and legitimate institution. An intensely unequal society depended on slaves to maintain itself.

Yielding to pressure, Dom Pedro II took an important step: his cabinet prepared a bill, presented to the parliament by Minister of Justice Eusébio de Queirós, which adopted effective measures for the extinction of the slave trade. Converted into Law No. 581 of September 4, 1850, its article 3 determined that:

The owner, the captain or master, the pilot, the boatswain and the overloader are guilty of the crime of importing or attempting to import slaves. The crew and those who help in the unloading of slaves in Brazilian territory are accomplices, as well as those who contribute to hide them from the authority's knowledge, or to subtract them from apprehension at sea, or in the act of unloading and being pursued.

One of its articles determined the trial of offenders should be done by the Admiralty, thus passing on to the imperial government the power to judge, which had previously been conferred on local judges.

There were so many protests that, in July 1852, Eusébio de Queirós had to appear before the Chamber of Deputies to appeal for a change in public opinion. He recalled that many farmers in the north faced financial difficulties, unable to pay their debts to the traffickers. Many had mortgaged their properties to speculators and large traffickers – including many Portuguese – to obtain funds to buy more captives. He also recalled that, if such a large quantity of African slaves continued to enter the Empire, there would be an imbalance between the categories of the population – free and slave – threatening the former. The so-called "good society" would be exposed to "very serious dangers", since the imbalance had already provoked numerous rebellions (such as that of Malê revolt, in Salvador in 1835).

In 1854, the Nabuco de Araújo Law, named after the Minister of Justice from 1853 to 1857, was approved. The last known landings took place in 1856.

Until 1850, immigration had been a spontaneous phenomenon. Between 1850 and 1870, it began to be promoted by the landowners. Coming first from Germany, unsuccessfully, and then from Italy, the immigrants, often deceived and with contracts that made them work in an almost slave-like regime, occupied themselves with rural work in the coffee economy. Because so many returned to their countries, it was necessary for consulates and the entities that protected them, such as some immigration promotion societies, to intervene. There were many regions where slaves were replaced by immigrants. Some cities in 1874 had 80% black rural workers, and in 1899, 7% black workers and 93% white.

In 1850, after the passage of the Eusébio de Queirós Law, slavery began to decline with the end of the slave trade. Progressively, European wage-earning immigrants replaced the slaves in the labor market. But it was only after the Paraguayan War (1864–1870) that the abolitionist movement gained momentum. Thousands of former slaves who returned from the war victorious, many even decorated, ran the risk of returning to their former condition under pressure from their former owners. The social problem became a political issue for the ruling elite of the Second Reign.

The abolition of the slave trade, its low reproduction rate, the various malaria epidemics, the constant escapes of slaves, the multiplication of quilombos, and the freeing of many slaves, including those who fought in the Paraguayan War, contributed significantly to the decrease in the number of slaves in Brazil at the time of the abolition.

Abolitionist campaign

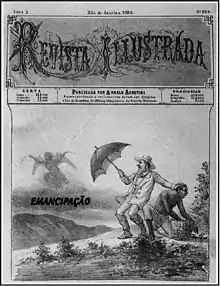

Around 1852, the first abolitionist associations and clubs emerged around the country, such as the Dois de Julho Abolitionist Society (1852), founded by young students from the Bahia Medical School.[3] In 1880, important politicians, such as Joaquim Nabuco and José do Patrocínio, created, in Rio de Janeiro, the Brazilian Society Against Slavery,[3] which stimulated the formation of dozens of similar associations around Brazil. Similarly, Nabuco's newspaper "O Abolicionista", and Angelo Agostini's "Revista Illustrada" served as models for other anti-slavery publications. Lawyers, artists, intellectuals, journalists, and politicians engaged in the movement and raised funds to pay for manumission. Although it is not widely known, the Positivist Church of Brazil, with Miguel Lemos and Raimundo Teixeira Mendes, had an outstanding role in the abolitionist campaign, including by delegitimizing slavery, seen, from then on, as a barbaric and backward way of organizing work and treating human beings.

Historical male characters such as Joaquim Nabuco, José do Patrocínio, José Mariano, André Rebouças, João Clapp, among others, took the lead in the abolitionist movement in much of the historiography produced.[3] With the amalgamation of 13 associations, the Brazilian Abolitionist Confederation was founded on August 13, 1883, and, beginning in 1884, there was an intensification of activism in public spaces and greater institutionalization of the movement.[4][5]

Women's participation was also of great relevance in the struggle for the end of slavery, acting in partnership with historical abolitionists or independently.[3] Noteworthy is the Ave Libertas Society, an abolitionist group founded in Pernambuco in 1884 and led by women, which, in the first year of activity, achieved the alforria of 200 captives.[3][6]

The Brazilian Freemasonry had a prominent participation in the abolitionist campaign, with almost all the main leaders of the abolition being Masons. José Bonifácio, pioneer of the abolition, Eusébio de Queirós, who abolished the slave trade, the Viscount of Rio Branco, responsible for the Rio Branco Law (a free womb law), and the abolitionists Luís Gama, Antônio Bento, José do Patrocínio, Joaquim Nabuco, Silva Jardim and Rui Barbosa were Masons. In 1839, Masons David Canabarro and Bento Gonçalves emancipated slaves during the Ragamuffin War.[7][8]

The students of the Faculty of Law of Recife mobilized and an abolitionist association is founded by students such as Plínio de Lima, Castro Alves, Rui Barbosa, Aristides Spínola, Regueira Costa, among others.

In São Paulo, the work of the ex-slave and one of the greatest heroes of the abolitionist cause, the lawyer Luís Gama, directly responsible for the liberation of more than a thousand captives, stands out. The Emancipating Society of São Paulo was also created in the capital city of São Paulo, with the participation of political leaders, farmers, college professors, journalists and, especially, students.

The country was seized by the abolitionist cause and, in 1884, Ceará and Amazonas abolished slavery in their territories. In the last years of slavery in Brazil, the abolitionist campaign became radicalized with the thesis "Abolition without compensation" launched by journalists, liberal professionals, and politicians who did not own rural properties.

The abolitionist laws

Rio Branco Law

The Liberal Party publicly committed itself to the cause of child birth as of that date, but it was the office of the Viscount of Rio Branco, of the Conservative Party, that enacted the first abolitionist law, the Rio Branco Law, on September 28, 1871. In defense of the law, the Viscount of Rio Branco presents slavery as an "injurious institution," less for the slaves and more for the country, especially for its external image.

After 21 years without any governmental measure regarding the end of slavery, the Rio Branco Law, better known as the Free Womb Law, was voted, which considered all children of slaves born from its publication, and intended to establish an evolutionary stage between slave labor and the free labor regime, without, however, causing abrupt changes in the economy or in society. In the Chamber of Deputies, the bill received 65 votes in favor and 45 against. Of these, 30 were from deputies from the three coffee provinces: Minas Gerais, São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. In the Imperial Senate, there were 33 votes in favor and 7 against. Among the votes against, 5 were from senators from the coffee provinces.[9]

According to the law, the slaves' children (called ingenuous) had two options: they could either stay with their mothers' masters until they reached the age of majority (21) or they could be handed over to the government. In practice, the slave owners kept the ingenuous on their properties, treating them as if they were slaves. In 1885, of the 400,000 ingenuous, only 118 were handed over to the government – the owners opted to free sick, blind, and physically handicapped slaves.

On the other hand, the Rio Branco Law had the merit of exposing the evils of slavery in the press and in public acts. In the 1890s, about half a million children were freed when they would have been entering productive age.[9]

The law declared free the children of slave women born from its date. The infant mortality rate among slaves increased, because, in addition to the terrible living conditions, the neglect of newborns grew. The financial aid foreseen by the Free Womb Law for farmers to pay for the expenses of raising their babies was never provided to the farmers:

- §1 of Law No. 2,040: The said minor children will remain in the power and under the authority of their mothers' masters, who will have the obligation of raising and caring for them until the age of 8. When the slave's child reaches this age, the mother's master will have the option of either receiving compensation of 600 thousand réis from the State, or of using the services of the minor until the age of 21. In the first case, the Government will receive the minor and dispose of him or her in accordance with this law.

Joaquim Nabuco wrote in 1883:

Abolitionism is first of all a political movement, for which, no doubt, interest in the slaves and compassion for their fate powerfully concur, but which is born from a different thought: that of rebuilding Brazil on free labor and the union of races in freedom.

— Joaquim Nabuco

Sexagenarian Law

From 1887 on, abolitionists began to act in the countryside, often helping mass escapes, sometimes causing farmers to be forced to hire their former slaves on a salaried basis. In 1887, several towns freed their slaves; their freedom was usually conditional on the provision of services (which, in some cases, implied servitude to other family members).

Ceará and Amazonas freed their slaves in 1885. Ceará's decision increased the pressure of public opinion on the imperial authorities. In 1885, the government gave in a little more and enacted the Saraiva-Cotegipe Law, which regulated the "gradual extinction of the servile element."[10]

The Saraiva-Cotegipe Law became known as the Sexagenarian Law. Born from a project of the deputy from Bahia, Rui Barbosa, this law freed all slaves over 60 years old, through financial compensation to their poorer owners to help these former slaves. However, this part of the law was never fulfilled and the slave owners were never compensated. Slaves who were between 60 and 65 years old were to "render services for 3 years to their masters and after the age of 65 they would be freed".

Few slaves reached this age, and those who arrived were already unable to guarantee their livelihood, even more because they had to compete with European immigrants. Moreover, in the census of 1872, which made the first general registration of slaves, many farmers had increased the age of their slaves to evade the 1872 registration, hiding the inbreds introduced by smuggling after the Eusébio de Queirós Law. Numerous robust and still young blacks were legally sexagenarians, being freed, in this case, by the Sexagenarian Law, still in working condition. The landowners would still try to annul the liberation, claiming to have been cheated because they were not compensated as promised by the law. The recently uncovered areas in the west region of São Paulo proved to be more disposed to the total emancipation of the slaves: rich and prosperous, they already exerted a great attraction on immigrants, and were better prepared for the regime of wage labor.

The escapes and the quilombos of the last slavery years in Brazil

The enslaved blacks and mulattos also began to participate more actively in the struggle, fleeing the farms and seeking freedom in the cities, especially after 1885, when corporal punishment of runaway slaves was prohibited when they were recaptured. Law No. 310, of October 15, 1886, revoked article 60 of the 1830 Criminal Code and Law No. 4, of June 10, 1835, in the part in which they imposed the penalty of scourging, and determined that "to the slave defendant, will be imposed the same penalties decreed by the Criminal Code and other legislation in force for any other offenders".

In the interior of São Paulo, led by the mulato Antônio Bento and his caifazes (a group of abolitionists), thousands of them escaped from the farms and settled in the Jabaquara Quilombo, in Santos. At this point, the abolitionist campaign became mixed with the republican campaign and gained an important reinforcement: the Brazilian Army publicly asked not to be used anymore to capture the fugitives. In the last years of slavery in Brazil, the abolitionist campaign adopted the slogan "Abolition without compensation". From abroad, especially from Europe, there were appeals and manifestos favorable to the end of slavery.

These mass escapes of slaves to the city of Santos generated violence, which was denounced in the debates on the Golden Law on November 9, 1888 in the General Chamber, by Representative General Andrade Figueira, who accused the São Paulo police (Public Force) and politicians of being conniving with these escapes, which led the São Paulo slave owners to free their slaves to avoid further violence:

The slaves fled en masse, damaging not only major economic interests, but also public safety interests: there were deaths, there were injuries, there was invasion of localities, there was terror poured out on every family, and that important province for many months remained in the most afflicting terror. Fortunately, the landowners of São Paulo understood that, in the face of the inaction of the Public Force, it would be better to capitulate before the disorder, so they gave freedom to the slaves.

— Andrade Figueira[11]

In the same vein, Joaquim Manuel de Macedo wrote in his book "As Vítimas-Algozes", denouncing the complicity of small commercial establishments, called venda, in the receiving of goods stolen from the farms by slaves and quilombolas:

The "venda" doesn't sleep: at late hours of the night the Quilombolas come, the runaway slaves and those holed up in the forests, bringing the tribute of their depredations on the neighboring or distant plantations to the venda owner, who collects the second harvest of what he didn't sow, and who always has in reserve for the Quilombolas food resources that they cannot do without, and also, not infrequently, gunpowder and lead for resistance in the case of attacks on the Quilombos.

— Joaquim Manuel de Macedo

Golden Law

.tif.jpg.webp)

On May 13, 1888, the imperial government yielded to pressure and Princess Isabel de Bragança signed the Golden Law, which extinguished slavery in Brazil. The decision displeased the farmers, who demanded compensation for the loss of "their goods". As they did not receive it, they joined the republican movement. By abandoning slavery, the Empire lost a pillar of political support.

The end of slavery, however, did not improve the social and economic condition of former slaves. Without schooling or a defined profession, for most of them the simple legal emancipation did not change their subordinate condition, nor did it help to promote their citizenship or social ascension. About the negative consequences of abolition without support to the slaves, in the book "1º Centenário de Antônio Prado", published in 1942, Everardo Valim Pereira de Souza made this analysis:

According to Antônio Prado's prediction, when the "13 of May Law" was quickly enacted, its effects were the most disastrous. The ex-slaves, used to the guardianship and curatorship of their former masters, scattered from the farms to "try their lives" in the cities; a life that consisted of: liquor by the gallon, misery, crime, illness and premature death. Two years after the decree of the law, maybe half of the new free element had already disappeared! The farmers could hardly find any "sharecroppers" willing to take care of the crops. All services were disorganized; so great was the social breakdown. The only part of São Paulo that suffered less was that which had already received some foreign immigration in advance; the Province as a whole lost almost its entire coffee crop for lack of pickers!

— Everardo Vallim Pereira de Souza[12]

The Golden Law was the crowning achievement of the first national mobilization of public opinion, in which politicians and poets, slaves, freedmen, students, journalists, lawyers, intellectuals and workers participated.

May 13 (once a national holiday during the Old Republic), because of Princess Isabel (daughter of Emperor Dom Pedro II), became the "freedom granting May 13", and highlights the support given by many white people of the time to the abolition of slavery.

The militants of the current black movement in Brazil evoke another May 13, which sees the abolition on May 13, 1888, as a soft coup aimed at curbing the advancement of the black population, which was, at the time, an oppressed minority.

In a third approach, May 13 is seen as a popular conquest. This is the focus of modern debates, which face the black problem as a national problem. The whole process of abolition in Brazil was slow and ambiguous, because, as José Murilo de Carvalho states: "Society was marked by values of hierarchy, of inequality; marked by the absence of the values of freedom and participation; marked by the absence of citizenship", and José Murilo also shows that it was not only large landowners who owned slaves. The same historian also says:

It was a society in which slavery as a practice, if not as a value, was widely accepted. Slaves were owned not only by the sugar and coffee barons. The small farmers of Minas Gerais, the small businessmen and bureaucrats of the cities, the secular priests and religious orders also owned slaves. Even more: the freedmen owned them. Blacks and mulattos who escaped slavery bought their own slaves if they had the resources. The penetration of slavery went even deeper: there are recorded cases of slaves who owned slaves. Slavery penetrated into the slave head itself. If it is true that no one in Brazil wanted to be a slave, it is also true that many accepted the idea of owning a slave.

— José Murilo de Carvalho

The same author also writes, commenting on the "burden of prejudices that structure our society, block mobility, and impede the construction of a democratic nation":

The battle of abolition, as some abolitionists realized, was a national battle. This battle continues today and is the task of the nation. The struggle of blacks, the most direct victims of slavery, for full citizenship must be seen as part of this larger struggle. Today, as in the 19th century, there is no possibility of escaping outside the system. There is no quilombo possible, not even a cultural one. The struggle is everyone's and it is inside the monster.

— José Murilo de Carvalho

The original document of the Golden Law, signed by Princess Isabel, is currently in the collection of the Brazilian National Archives in the city of Rio de Janeiro.

Compensation to former slave owners

Although the total abolition of slavery only happened in 1888, with the Golden Law, the laws of the Free Womb (Law No. 2,040, of 1871) and of the Sexagenarians (Law No. 3,270, of 1885) already provided for indemnities from the slave owners in case of liberation of the slaves they owned.

In Perdigão Malheiro's understanding: "if slavery owes its existence and preservation exclusively to positive law, it is evident that positive law can extinguish it. The obligation to indemnify is not strict, according to absolute or Natural law; it is only equitable as a consequence of the positive law itself, which acquiesced to the fact and gave it force as if it were a true and legitimate property; this fictitious property is rather a toleration by the law for special reasons of public order than the recognition of a right that has its basis and foundation in the eternal laws. In the trial, one should always decide as favorably as possible to freedom. So that only those on whom there is a clear right of ownership should be declared slaves and kept as such; and even then, if it is not possible, strictly or at least in equity and in favor of liberty, to exempt them from captivity, if only by means of compensation to the master."[13]

The Free Womb Law states, in its article 1, §1, that the children of slave women up to 8 incomplete years of age are the property of their mothers' owners. After the age of 8, the masters can choose between freeing the child and receiving an indemnity of 600 thousand réis from the State, or using the services of the child until the age of 21. In article 8 of the same Law, it is determined that all slaves should be registered with a declaration of name, sex, status, fitness for work and filiation.[14]

Following what was decided about the slave registration, the Sexagenarian Law, in its article 1, §3, stipulates the value of each slave according to his age, varying from 200 thousand réis to 900 thousand réis, being the value of female slaves 25% lower. Paragraph 8 of the same article deals with the indemnification of the masters in case the registration of the slaves is not done, if it is the obligation of any of their employees, since the unregistered slaves would be automatically freed. Article 3 deals with the indemnity of the masters based on the list value of the slaves, and a percentage of the value would be deducted from their price according to the time it took for the slave to be freed from his registration, varying from 2% deduction if freed in the first year, to 12% deduction if freed from the eleventh year onwards. In the case of slaves between the ages of 60 and 65, according to article 3, §10, the compensation to the masters for their alforria is in the form of service for a period of 3 years. After the age of 65, the slaves are freed from any obligation to the master upon their alforria.[10] Article 4, §4, makes it explicit, however, that the regalia to indemnity for the slaves' alforria will cease with the extinction of slavery, which occurred with the Abolition of Slavery in 1888.

Debates in the Chamber of Deputies

On August 23, 1871, before the publication of the Free Womb Law (promulgated on the following month, guaranteeing freedom to the children of slaves born in Brazil), the Senate decided, in a plenary session, to authorize the release of the nation's slaves, whose services were given in usufruct to the Crown, regardless of compensation.

The last years before the abolition of slavery were tumultuous in the Chamber of Deputies. Trying to speed up the emancipation process, bills were introduced to encourage the end of slavery through compensation. On July 15, 1884, Congressman Antônio Felício dos Santos presented Bill No. 51 "making provision for the re-registration of all slaves until July 1885, leaving free those who were not registered and whose value would be arbitrated according to the process of the law for liberation by the emancipation fund."[15] The emancipation fund sought to gather, in a pecuniary manner, resources to obtain as many manumissions as possible. The indemnity would ensure the legitimacy of private property, a principle denied after the Abolition Law was promulgated, by declassifying the slave as an object, a property. This fund was created by the Free Womb Law, in its article 3. The bill proposed by Deputy Antônio Felício dos Santos had, therefore, as its primary function, the end of slavery, for the simple fact that if the required new registration was not carried out, the slave owner would lose possession of the slave, leaving him only the just compensation, provided for by the emancipation fund.

The abolitionist movement suffered opposition from the slave society in the Chamber. On September 3, 1884, the deputy and first-secretary, Leopoldo Augusto Diocleciano de Melo e Cunha, proceeds to testify on Decree No. 9,270 prepared by the then Minister and Secretary of State for the Affairs of the Empire Filipe Franco de Sá, which reads as follows: "Using the attribution given to me by the Political Constitution of the Empire in article 101, §5, and having heard the Council of State, I decide to dissolve the Chamber of Deputies and convene another one, which will meet extraordinarily on March 1 of the next year." The reason for this dissolution was the oppositions created by Bill No. 48, which sought the implementation of new taxes to increase the Emancipation Fund and granted freedom to slaves over 60 years old without compensation.

The dissolution of the Chamber of Deputies sought to curb the abolitionist movements that were taking shape, but the opposition could not contain the liberal ideas.

A last attempt to ensure the right to indemnity after slavery was proposed on May 24, 1888[16] with the intention of establishing, as well described in its preamble: "complementary provisions to Law No. 3,353 of May 13, 1888, which extinguished slavery". Deputy Antônio Coelho Rodrigues sent, to the Chamber of Deputies, Bill No. 10, which ordered the government to indemnify, in public debt bonds, the losses resulting from the extinction of the servile element. This bill was not even deliberated, since it went against what had already been established in the Golden Law, the Sexagenarian Law, and the Free Womb Law.

After the prohibition of slavery

On December 14, 1890, by decree, in a proposal made by Joaquim Nabuco in 1888, Rui Barbosa, sworn in as Minister of Finance, requested the destruction of all the registration books, documents and papers relating to slavery in the Ministry of Finance, so as to prevent any research at that time and after it aimed at compensating former slave owners. However, this decision was only made effective on May 13, 1891, during the administration of Tristão de Alencar Araripe, who, in the minutes of the meeting that culminated in such destruction, ordered an analysis of the slave situation from the legal point of view a year earlier, and the abolitionist tendencies at that time. Rui Barbosa saw slavery as the greatest of Brazil's problems, and would not tolerate any compromise regarding its end, following the example of the Free Womb and Sexagenarian Laws: if slavery is to cease to exist, let it be completely extinguished. The Minister affirmed that if anyone was to be compensated, it should be the former slaves themselves. However, knowing the impossibility of this happening, the idea of burning his collection was initiated.[17]

Compensation to former slaves

A plan of indemnification for the freedmen was mentioned by Princess Isabel in a letter sent to the Viscount of Santa Vitória on August 11, 1889.[18] The plan involved the use of funds donated by the then Viscount, which would come from his bank. The starting date for the proceedings was supposed to be the inauguration of the new legislature on November 20, 1889, and the princess intended to execute it with the help of influential abolitionists in the government and in the media such as Joaquim Nabuco and José do Patrocínio. The original letter is currently in the collection of the Imperial Museum of Brazil and is part of the documents ceded to the museum by the Visconde de Mauá Museum.[19] A copy of the letter is also in the collection of the Araraquara City Council since September 05, 2019 by determination of Opinion No. 392/2019 of the Commission of Justice, Legislation and Writing of the legislative house.

With the Proclamation of the Republic on November 15, 5 days before the beginning of the new legislature, the possibility of executing the plan was exhausted. The subsequent burning of the registration books and tax collection books of former slaves determined by an order of the then Minister of Finance Rui Barbosa on December 14, 1890 also prevented any reimbursement to the freedmen.[20] Records such as these are also used today by countries with a history of slavery so that people can identify their ancestors.[21][22] Although this event was of paramount importance for preventing former slave owners from obtaining compensation,[23] it is currently regarded by some researchers as a crucial factor generating the "erasure of black memory" and constant among the central elements of the patterns of disrespect towards black groups in Brazil.[24][25]

Post-abolition

.jpg.webp)

If on the one hand the abolition of slavery represented a great ethical and humanitarian achievement, on the other hand it proved problematic, because in many ways, the situation of the freedmen worsened. Since the government did not organize any program for their integration into society, they were left to their own devices. In the context of a white dominant society deeply steeped in racism, discrimination continued to manifest itself at all levels. The vast majority of freedmen remained marginalized and deprived of access to health, education, vocational training, and citizenship. Many lost their jobs and their homes and were forced to migrate in search of new jobs, which were generally precarious and difficult. Misery became commonplace. The post-abolition period was the beginning of a long and arduous process of struggle for rights, dignity, recognition, and inclusion, which to this day is still not concluded.[26][27]

See also

References

- ↑ Senado Federal (2012). "Representação de José Bonifácio". A abolição no Parlamento: 65 anos de luta (1823–1888). Vol. 1. pp. 30–47.

- ↑ Amaral (2006). Dicionário de História de São Paulo. p. 21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Barreto, Maria Renilda N.; Silva, Wladimir Barbosa (2014). "Mulheres e Abolição: Protagonismo e Ação". Revista da ABPN (in Portuguese). Vol. 6, no. 14. pp. 50–62.

- ↑ Alonso, Angela (2011). "Associativismo avant la lettre: as sociedades pela abolição da escravidão no Brasil oitocentista". Sociologias (in Portuguese). 13 (28): 116–199. doi:10.1590/S1517-45222011000300007. ISSN 1517-4522 – via SciELO.

- ↑ Alonso, Angela (2014). "O abolicionismo como movimento social". Novos Estudos CEBRAP (in Portuguese) (100): 115–127. doi:10.1590/S0101-33002014000300007. ISSN 0101-3300 – via SciELO.

- ↑ Ferreira (1999). Suaves amazonas: mulheres e abolição da escravatura no nordeste. ISBN 978-85-7315-153-4.

- ↑ Castellani (2001). A Maçonaria na Década da Abolição e da República.

- ↑ Castellani (2007). A Ação Secreta da Maçonaria na Política Mundial.

- 1 2 Senado Federal (2000). Sociedade e História do Brasil – Do cativeiro à liberdade. p. 23.

- 1 2 "Saraiva-Cotegipe Law". Law No. 3,270 of September 28, 1885 (in Portuguese).

- ↑ Câmara dos Deputados (1888). Annaes do Parlamento Brazileiro (in Portuguese). Vol. 1. Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional. p. 52.

- ↑ Souza (1946). 1º Centenário do Conselheiro Antônio Prado.

- ↑ Malheiro (2008). A Escravidão no Brasil (PDF). Vol. 1.

- ↑ "Rio Branco Law". Law No. 2,040 of September 28, 1871 (in Portuguese).

- ↑ Silva Neto (2003). A construção da democracia: síntese histórica dos grandes momentos da Câmara dos Deputados, das Assembléias Nacionais Constituintes do Congresso Nacional.

- ↑ Senado Federal (2012). A abolição no Parlamento: 65 anos de luta (1823–1888). Vol. 2.

- ↑ Mota; Ferreira (2010). Os juristas na formação do Estado-Nação Brasileiro (1850–1930).

- ↑ Fonseca (2009). Políticas Públicas e Ações Afirmativas. pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Mesquita (2009). O "Terceiro Reinado": Isabel de Bragança, A Imperatriz que Não Foi. pp. 123–124.

- ↑ Skidmore (1976). Preto no Branco: Raça e Nacionalidade no Pensamento Brasileiro. pp. 220–221.

- ↑ "Online slave registers from Curaçao allow descendants to find ancestors". DutchNews. August 17, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ↑ "Suriname: registers totslaafgemaakten (Slavenregisters), 1826–1863". Nationaal Archief (in Dutch). Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ↑ Godoy, Arnaldo Sampaio de Moraes (September 13, 2015). "Rui Barbosa e a polêmica queima dos arquivos da escravidão". Conjur (in Portuguese). Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- ↑ Duarte, Evandro Piza; Carvalho Neto, Menelick de; Scotti, Guilherme (2015). "Ruy Barbosa e a Queima dos Arquivos: As Lutas pela Memória da Escravidão e os Discursos dos Juristas". Universitas Jus (in Portuguese). 26 (2). doi:10.5102/unijus.v26i2.3553. ISSN 1982-8268.

- ↑ Habeas Corpus No. 82,424 (Court case) (in Portuguese). STF. 2004.

- ↑ Rios, Ana Maria; Mattos, Hebe Maria (2004). "O pós-abolição como problema histórico: balanços e perspectivas". Topoi (in Portuguese). 5 (8): 170–198. doi:10.1590/2237-101X005008005 – via SciELO.

- ↑ Maia, Beatriz (May 14, 2018). "Cinco visões sobre os 130 anos da abolição". Jornal da Unicamp (in Portuguese).

Bibliography

- Amaral, Antônio Barreto (2006). Dicionário de História de São Paulo (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Imprensa Oficial.

- Barbosa, Rui, Emancipação dos Escravos (1884) Relatório sobre o Projeto N.º 48 das Comissões Reunidas de Orçamento e Justiça Civil da Câmara dos Deputados. Rio de Janeiro: Tipografia Nacional.

- Câmara dos Deputados (1888). Annaes do Parlamento Brazileiro (in Portuguese). Vol. 1. Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional.

- Castellani, José (2001). A Maçonaria na Década da Abolição e da República (in Portuguese). A Trolha.

- Castellani, José (20017. A Ação Secreta da Maçonaria na Política Mundial (in Portuguese). Landmark.

- Ferreira, Luzilá Gonçalves (1999). Suaves amazonas: mulheres e abolição da escravatura no nordeste (in Portuguese). Recife: UFPE. ISBN 978-85-7315-153-4.

- Fonseca, Dagoberto José (2009). Políticas Públicas e Ações Afirmativas (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Selo Negro.

- Malheiro, Agostinho Marques Perdigão (2008). A Escravidão no Brasil (in Portuguese). Vol. 1. Rio de Janeiro: Typografia Nacional.

- Mesquita, Maria Luiza de Carvalho (2009). O “Terceiro Reinado”: Isabel de Bragança, A Imperatriz que Não Foi (in Portuguese). Vassouras: Universidade Severino Sombra.

- Mota, Carlos Guilherme; Ferreira, Gabriela Nunes (2010). Os juristas na formação do Estado-Nação Brasileiro (1850–1930) (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Saraiva. ISBN 978-85-02-08750-7.

- Senado Federal (2000). Sociedade e História do Brasil – Do cativeiro à liberdade (in Portuguese). Brasília: Instituto Teotônio Vilela.

- Senado Federal (2012). A abolição no Parlamento: 65 anos de luta (1823–1888) (in Portuguese). Vol. 1. Brasília: Senado Federal.

- Senado Federal (2012). A abolição no Parlamento: 65 anos de luta (1823–1888) (in Portuguese). Vol. 2. Brasília: Senado Federal.

- Silva Neto, Casimiro Pedro da (2003). A construção da democracia: síntese histórica dos grandes momentos da Câmara dos Deputados, das Assembléias Nacionais Constituintes do Congresso Nacional (in Portuguese). Btrasília: Camara dos Deputados.

- Skidmore, Thomas Elliot (1976). Preto no Branco: Raça e Nacionalidade no Pensamento Brasileiro (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra.

- Souza, Everardo Vallim Pereira de (1946). 1º Centenário do Conselheiro Antônio Prado (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Revista dos Tribunais.

.svg.png.webp)