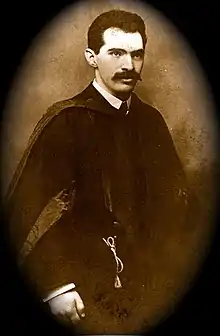

Abraham Wolf (1876 – 19 May 1948) was a Russian-born English historian, philosopher, writer, and rabbi.[1] Born to a shopkeeper and his wife, Wolf simultaneously studied mental and moral philosophy at the University of London and Semitic studies at the Jews' College. He later attended St John's College on a Jews' College scholarship and his dissertation was published by Cambridge University Press in 1905.[2]

Wolf is credited with introducing the history of science to University College London,[3] where he lectured as Professor of Logic and Scientific Method from 1920 to 1941.[4][5] Wolf was a scientific rationalist who embraced ideas held by Baruch Spinoza—many of whose works Wolf translated into English—and Maimonides. Wolf's 1915 collection of lectures on Friedrich Nietzsche was "one of the earliest English discussions of the thinker".[6]

Wolf was the co-editor of the 14th edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica, published in 1929.[7] Two volumes of his A History of Science, Technology, and Philosophy in the 16th and 17th Centuries, written with the assistance of University College astronomer Angus Armitage,[8] were published in 1935; two further volumes, A History of Science, Technology, and Philosophy in the 18th Century, were published two years later.[9] He was also a rabbi at the Manchester Reform Synagogue and a frequent contributor to the Jewish Quarterly Review. However, he would experience a tension between his beliefs in Reform Judaism and science,[2] and he eventually resigned from the rabbinate in 1907.[10] By 1933, Wolf had ceased to write anything noteworthy on Judaism, having devoted himself to philosophy and secular scholarship.[11]

From 1942 until his death in 1948, he was an honorary associate of the Rationalist Press Association.[12] In 1950, Wolf's private collection of books by and about Spinoza—which took forty-five years to amass and was then the largest collection of its kind in the world—was transferred to UCLA.[13][14]

References

Citations

- ↑ Haberman 1991, p. 267.

- 1 2 Haberman 1991, p. 269.

- ↑ Smeaton 1997, p. 25.

- ↑ Howson 2011, p. 496.

- ↑ Piercey 2005, p. 1162.

- ↑ Piercey 2005, p. 1164.

- ↑ Edmund 2005, p. 460.

- ↑ Smeaton 1978, p. 99.

- ↑ Piercey 2005, p. 1163.

- ↑ Haberman 1991, pp. 288–289.

- ↑ Haberman 1991, p. 290.

- ↑ Haberman 1991, p. 268.

- ↑ Brisman 1969, p. 47.

- ↑ Zeidberg, David S. "The Abraham Wolf Spinoza Collection". UCLA Library. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

Sources

- Brisman, Shimeon (1969). "The Jewish Studies Collection at UCLA". In Solomon Grayzel (ed.). Jewish Book Annual. Vol. 27. Jewish Book Council of America.

- Edmund, Norman W. (2005). End the Biggest Educational and Intellectual Blunder in History. Scientific Method Publishing Company. ISBN 9780963286666.

- Haberman, Jacob (1991). "Abraham Wolf: A Forgotten Jewish Reform Thinker". The Jewish Quarterly Review. University of Pennsylvania Press. 81 (3/4): 267–304. doi:10.2307/1455321. JSTOR 1455321.

- Howson, Susan (2011). Lionel Robbins. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139003544. ISBN 9781139501095.

- Piercey, Robert (2005). "Wolf, Abraham". In Stuart Brown (ed.). Dictionary of Twentieth-Century British Philosophers. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781441192417.

- Smeaton, William A. (1978). "Angus Armitage". The British Journal for the History of Science. Cambridge University Press. 11 (1): 99–100. doi:10.1017/S0007087400016204.

- Smeaton, William A. (1997). "History of Science at University College London: 1919–47". The British Journal for the History of Science. Cambridge University Press. 30 (1): 25–28. doi:10.1017/S0007087496002877. JSTOR 4027897.

External links

Works related to Abraham Wolf at Wikisource

Works related to Abraham Wolf at Wikisource