Acceptance angle is the maximum angle at which incoming sunlight can be captured by a solar concentrator. Its value depends on the concentration of the optic and the refractive index in which the receiver is immersed. Maximizing the acceptance angle of a concentrator is desirable in practical systems and it may be achieved by using nonimaging optics.

For concentrators that concentrate light in two dimensions, the acceptance angle may be different in the two directions.

Definition

The "acceptance angle" figure illustrates this concept.

The concentrator is a lens with a receiver R. The left section of the figure shows a set of parallel rays incident on the concentrator at an angle α < θ to the optical axis. All rays end up on the receiver and, therefore, all light is captured. In the center, this figure shows another set of parallel rays, now incident on the concentrator at an angle α = θ to the optical axis. For an ideal concentrator, all rays are still captured. However, on the right, this figure shows yet another set of parallel rays, now incident on the concentrator at an angle α > θ to the optical axis. All rays now miss the receiver and all light is lost. Therefore, for incidence angles α < θ all light is captured while for incidence angles α > θ all light is lost. The concentrator is then said to have a (half) acceptance angle θ, or a total acceptance angle 2θ (since it accepts light within an angle ±θ to the optical axis).

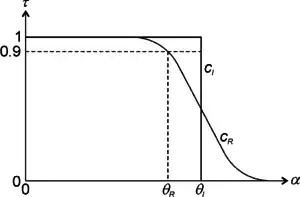

Ideally, a solar concentrator has a transmission curve cI as shown in the "transmission curves" figure. Transmission (efficiency) is τ = 1 for all incidence angles α < θI and τ = 0 for all incidence angles α > θI.

In practice, real transmission curves are not perfect and they typically have a shape similar to that of curve cR, which is normalized so that τ = 1 for α = 0. In that case, the real acceptance angle θR is typically defined as the angle for which transmission τ drops to 90% of its maximum.[1]

For line-focus systems, such as a trough concentrator or a linear Fresnel lens, the acceptance angle is one dimensional, and the concentration has only weak dependence on off-pointing perpendicular to the focus direction. Point focus systems, on the other hand, are sensitive to off-pointing in both directions. In the general case, the acceptance angle in one direction may be different from the other.

Acceptance angle as a tolerance budget

The acceptance angle θ of a concentrator may be seen as a measure of how precisely it must track the sun in the sky. The smaller the θ, the more precise the tracking needs to be or the concentrator will not capture the incoming sunlight. It is, therefore, a measure of the tolerance a concentrator has to tracking errors.

However, other errors also affect the acceptance angle. The "optical imperfections" figure shows this.

The left part of the figure shows a perfectly made lens with good optical surfaces s1 and s2 capturing all light rays incident at an angle α to the optical axis. However, real optics are never perfect and the right part of the figure shows the effect of a badly made bottom surface s2. Instead of being smooth, s2 now has undulations and some of the light rays that were captured before are now lost. This decreases the transmission of the concentrator for incidence angle α, decreasing the acceptance angle. Actually, any imperfection in the system such as:

- tracking inaccuracy

- imperfectly manufactured optics

- optical aberrations

- imperfectly assembled components

- movements of the system due to wind

- finite stiffness of the supporting structure

- deformation due to aging

- other imperfections in the system

contributes to a decrease in the acceptance angle of the concentrator. The acceptance angle may then be seen as a "tolerance budget" to be spent on all these imperfections. At the end, the concentrator must still have enough acceptance to capture sunlight which also has some angular dispersion θS when seen from earth. It is, therefore, very important to design a concentrator with the widest possible acceptance angle. That is possible using nonimaging optics, which maximize the acceptance angle for a given concentration.

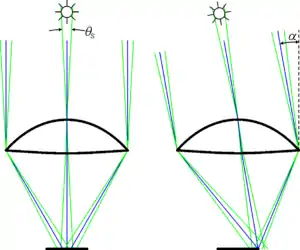

Figure "angular aperture of sunlight" on the right shows the effect of the angular dispersion of sunlight on the acceptance angle.

Sunlight is not a set of perfectly parallel rays (shown in blue), but it has a given angular aperture θS, as indicated by the green rays. If the acceptance angle of the optic is wide enough, sunlight incident along the optical axis will be captured by the concentrator, as shown in the "angular aperture of sunlight" figure. However, for wider incidence angles α some light may be lost, as shown on the right. Perfectly parallel rays (shown in blue) would be captured, but sunlight, due to its angular aperture, is partially lost.

Parallel rays and sunlight are therefore transmitted differently by a solar concentrator and the corresponding transmission curves are also different. Different acceptance angles may then be determined for parallel rays or for sunlight.

Concentration acceptance product (CAP)

For a given acceptance angle θ, for a point-focus concentrator, the maximum concentration possible, Cmax, is given by

- ,

where n is the refractive index of the medium in which the receiver is immersed.[2] In practice, real concentrators either have a lower than ideal concentration for a given acceptance or they have a lower than ideal acceptance angle for a given concentration. This can be summarized in the expression

- ,

which defines a quantity CAP (concentration acceptance product), which must be smaller than the refractive index of the medium in which the receiver is immersed.

For a linear-focused concentrator, the equation is not squared[3]

The Concentration Acceptance Product is a consequence of the conservation of etendue. The higher the CAP, the closer the concentrator is to the maximum possible in concentration and acceptance angle.

See also

- Etendue

- Guided ray, acceptance angle context for optic fibres

References

- ↑ Benitez, Pablo; et al. (26 April 2010). "High performance Fresnel-based photovoltaic concentrator". Optics Express. 18 (S1): A25-40. Bibcode:2010OExpr..18S..25B. doi:10.1364/OE.18.000A25. PMID 20588570.

- ↑ Chaves, Julio (2015). Introduction to Nonimaging Optics, Second Edition. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1482206739.

- ↑ See: http://www.powerfromthesun.net/Book/chapter09/chapter09.html . Note that in this derivation theta is the full angle, not the half-angle defined here.