The Accession Day tilts were a series of elaborate festivities held annually at the court of Elizabeth I of England to celebrate her Accession Day, 17 November, also known as Queen's Day.[1] The tilts combined theatrical elements with jousting, in which Elizabeth's courtiers competed to outdo each other in allegorical armour and costume, poetry, and pageantry to exalt the queen and her realm of England.[2]

The last Elizabethan Accession Day tilt was held in November 1602; the queen died the following spring. Tilts continued as part of festivities marking the Accession Day of James I, 24 March, until 1624, the year before his death.[3]

Origins

Sir Henry Lee of Ditchley, Queen's Champion, devised the Accession Day tilts, which became the most important Elizabethan court festival from the 1580s.[4] The celebrations are likely to have begun somewhat informally in the early 1570s.[2] By 1581, the Queen's Day tilts "had been deliberately developed into a gigantic public spectacle eclipsing every other form of court festival", with thousands in attendance; the public were admitted for a small charge.[5] Lee himself oversaw the annual festivities until he retired as Queen's Champion at the tilt of 1590, handing over the role to George Clifford, 3rd Earl of Cumberland.[6] Following Lee's retirement, orchestration of the tilts fell to the Earl of Worcester in his capacity of Master of Horse and to the queen's favourite, the Earl of Essex, although Lee remained as a sort of Master of Ceremonies at the request of the queen.[7]

The pageants were held at the tiltyard at the Palace of Whitehall,[8] where the royal party viewed the festivities from the Tiltyard Gallery. The Office of Works constructed a platform with staircases below the gallery to facilitate presentations to the queen.[9]

Participants

Knights

Tilt lists for the Accession Day pageants have survived; these establish that the majority of the participating jousters came from the ranks of the Queen's Gentlemen Pensioners. Entrants included such powerful members of the court as the Earl of Bedford, the Earl of Oxford, the Earl of Southampton, Lord Howard of Effingham,[11] and the Earl of Essex.[12] Many of those participating had seen active service in Ireland or on the Continent, but the atmosphere of romance and entertainment seems to have predominated over the serious military exercises that were medieval tournaments.[13] Sir James Scudamore, a knight who tilted in the 1595 tournament, was immortalised as "Sir Scudamour" in Book Four of The Faerie Queene by Edmund Spenser.

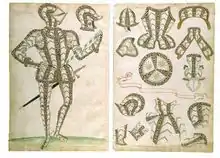

Knights participating in the spectacle entered in pageant cars or on horseback, disguised as some heroic, romantic, or metaphorical figure, with their servants in fancy dress according to the theme of the entry. A squire presented a pasteboard pageant shield decorated with the character's device or impresa to the Queen and explained the significance of his disguise in prose or poetry.[11] Entrants went to considerable expense to devise themes, order armour and costumes for their followers, and in some cases to hire poets or dramatists and even professional actors to carry out their programmes.

Classical, pastoral, and Arthurian settings were typically combined with story lines flattering to the queen, but serious subtexts were common, especially among those who used these occasions to express public contrition or desolation for having aroused the queen's displeasure, or to plead for royal favour.[15] In the painting on the left, Essex wears black (sable) armour, which he wore as part of his 1590 entrance to the tilts. At this particular tilt, Essex entered as the head of a funeral procession, carried on a bier by his attendants. This was meant to atone for his failure to subdue Ireland, but Elizabeth was not impressed and did not forgive him readily.

Poets

Poets associated with court circles who wrote allegorical verses to accompany the knights' presentations include John Davies, Edward de Vere, Philip Sidney[16] and the young Francis Bacon, who composed speeches and helped stage presentations for his patron, the Earl of Essex.[17] Sidney, in particular, as both poet and knight, embodied the chivalric themes of the tilts; a remembrance of Sidney was part of the tilt programme of 1586, the year after his death.[18] Sidney's friend and protégé Sir James Scudamore, who would go on to be one of the primary competitors in the Accession Day tilt in 1595, carried the pennant of Sidney's arms at the age of eighteen.[19] Edmund Spenser wrote of The Faerie Queene, which turns upon the Accession Day festivities as its fundamental structural device: "I devise that the Faery Queen kept her Annuall feast xii. days, upon which xii. severall days, the occasions of the xii. severall adventures hapned, which being undertaken by xii. severall knights, are in these xii. books severally handled and discoursed";[20]

A visitor's account

%252C_Third_Earl_of_Cumberland_MET_DP295743.jpg.webp)

The fullest straightforward account of a Tilt is by Lupold von Wedel, a German traveller who saw the 1584 celebrations:

Now approached the day, when on November 17 the tournament was to be held... About twelve o'clock the queen and her ladies placed themselves at the windows in a long room at Weithol [Whitehall] palace, near Westminster, opposite the barrier where the tournament was to be held. From this room a broad staircase led downwards, and round the barrier stands were arranged by boards above the ground, so that everybody by paying 12d. would get a stand and see the play... Many thousand spectators, men, women and girls, got places, not to speak of those who were within the barrier and paid nothing.

During the whole time of the tournament all those who wished to fight entered the list by pairs, the trumpets being blown at the time and other musical instruments. The combatants had their servants clad in different colours, they, however, did not enter the barrier, but arranged themselves on both sides. Some of the servants were disguised like savages, or like Irishmen, with the hair hanging down to the girdle like women, others had horses equipped like elephants, some carriages were drawn by men, others appeared to move by themselves; altogether the carriages were very odd in appearance. Some gentlemen had their horses with them and mounted in full armour directly from the carriage. There were some who showed very good horsemanship and were also in fine attire. The manner of the combat each had settled before entering the lists. The costs amounted to several thousand pounds each.

When a gentleman with his servants approached the barrier, on horseback or in a carriage, he stopped at the foot of the staircase leading to the queen's room, while one of his servants in pompous attire of a special pattern mounted the steps and addressed the queen in well-composed verses or with a ludicrous speech, making her and her ladies laugh. When the speech was ended he in the name of his lord offered to the queen a costly present... Now always two by two rode against each other, breaking lances across the beam... The fête lasted until five o'clock in the afternoon...[21]

See also

Notes

- ↑ which was elevated into a Protestant feast day by adding it to the Anglican Church calendar: "All over England the Queen's subjects expressed their joy in her Government by prayers and sermons, bell-ringing, bonfires and feasting", notes Roy C. Strong, "The Popular Celebration of the Accession Day of Queen Elizabeth I" Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 21.1/2 (January 1958:86-103) p 87; see also, whereon sttod a lyon and a dragon, supporters Strong (1984):19 and Hutton 1994:146-151

- 1 2 Strong 1977, p. 129-133

- ↑ Strong (1987):137-138; Young, p. 208

- ↑ Festivities surrounding installations of the Order of the Garter were less frequent, less elaborate and less public.

- ↑ Strong 1977, p. 133, & 1984:51

- ↑ The ceremonial transfer is described in detail in Yates, p. 102-103

- ↑ Yates, p. 104

- ↑ except in 1593, when they were relocated to the grounds of Windsor Castle due to an outbreak of plague in London; see Young, p. 122, 169.

- ↑ Young, p. 119-122

- ↑ Young p. 136

- 1 2 Strong 1977, p. 135

- ↑ Hutton 1994, p. 146-151

- ↑ Strong (1984):51

- ↑ The armet shown was made by restorer Daniel Tachaux in 1915 to replace the missing original, and faithfully reproduces the style's distinctive high visor.

- ↑ Young, p. 167-77

- ↑ 'Two Songs for an Accession Day Tilt', in Sir Philip Sidney: The Major Works, Oxford University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-19-284080-0

- ↑ 'A Conference of Pleasure' (speeches composed for the Earl of Essex for the Queen’s Accession Day Tilt, 1594): 'In Praise of Knowledge', 'In Praise of Fortitude', 'In Praise of Love', 'In Praise of Truth'; 'The Device of the Indian Prince' (Speeches composed for the Earl of Essex for the Queen’s Accession Day Tilt, 1594): 'Squire', 'Hermit', 'Soldier', 'Statesman'. Dates of Francis Bacon's works, retrieved 29 November 2007 Archived October 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine; and see Strong (1987), p. 137

- ↑ Yates, p.100

- ↑ Atherton, Ian. Ambition and Failure in Stuart England: The Career of John, First Viscount Scudamore, Manchester University Press, 1999. p.34

- ↑ Letter from Spenser to Sir Walter Raleigh quoted in Roy C. Strong 1958:86.

- ↑ SHAFE Archived December 3, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, New Series IX (1895)pp. 258-9, quoted Strong, 1984, Yates Astrea etc

References

- Hutton, Ronald: The Rise and Fall of Merry England: The Ritual Year 1400-1700, Oxford University Press, 1994, ISBN 978-0-19-820363-6

- Strong, Roy: The Cult of Elizabeth: Elizabethan Portraiture and Pageantry, Thames and Hudson, 1977, ISBN 0-500-23263-6

- Strong, Roy; Art and Power; Renaissance Festivals 1450-1650, 1984, The Boydell Press, ISBN 0-85115-200-7

- Yates, Frances A.: Astraea: The Imperial Theme in the Sixteenth Century, Routledge & Keegan Paul, 1975, ISBN 0-7100-7971-0

- Young, Alan: Tudor and Jacobean Tournaments, Sheridan House, 1987, ISBN 0-911378-75-8