Active destocking in supply chain management is an active decision to reduce the inventory-to-sales ratio[1] of a company. The inventory can include finished products, raw materials and goods in process. In general, active destocking is done following an autonomous, often financial decision by a company to improve its efficiency, free up cash and reduce its costs. Decisions for active destocking in general are made by financial executives or general managers.

Active destocking should be distinguished from reactive destocking. Reactive destocking is a reduction of the inventory when expected demand goes down. When a company is only doing reactive destocking the inventory-to-sales ratio[1] remains unchanged. Reactive destocking in general is done by the operational managers of the logistical activities, without additional instructions.

The terms active destocking and reactive destocking were first used in an article about the Lehman Wave, published by Dutch researchers in 2009.[2][3]

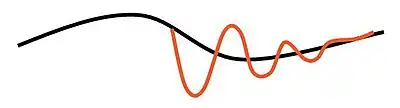

A Lehman wave refers to an economy-wide fluctuation in production and in economic activity with a wavelength of between 12 and 18 months, driven by a sudden major disruption of the economic system. The Lehman wave is a dampened, wave-like fluctuation around equilibrium. The amplitude of the Lehman wave is larger for a business that is further away from its end market than for a business that is closer to its end market, which difference is caused by cumulative destocking of the intermediate supply chain.

The first described Lehman wave was caused by global active destocking and reactive destocking after the financial panic following the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers on September 15, 2008. The Lehman wave can have strong effects on the sales volume and therefore on the profitability of companies higher in the value chain.[4]

As cause of the Lehman wave

The strong dip in the manufacturing industry seen at the end of 2008 was caused by cumulative and synchronized active destocking followed by reactive destocking, triggered by the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers. Said bankruptcy created a sudden peak in the Libor interest rate, causing the banks to recall credit and companies to start freeing up cash by active destocking, so reducing their stocks. When the customers of a company start active destocking it is experienced by said company as lower demand and said company will respond by doing reactive destocking. End markets also responded by going down, but slower and in most markets not so strongly. The drop in end market plus the active and reactive destocking created a damped wave with a large amplitude, the so-called Lehman wave.

Relation between inventory to sales ratio and inventory

When a company takes an active destocking decision, said company expresses the wish to reduce the inventory-to-sales ratio. In practice, the actual inventory can go up before going down, depending on the behavior of the other firms in the supply chain.

Effect on sales

Active destocking explains why some companies can see a strong dip in sales while their end markets are fairly stable. If the supply chain between a company and its end-customer would have a stock depth of "250 days' sales", meaning that it takes at least 250 days for a molecule to travel from a company's warehouse to the final consumer, and if each firm in such a 250-day supply chain decides to do active destocking of 12%, an amount of stock equal to 30 days' sales (a whole month) is taken out of the chain. For a company at the beginning of the supply chain this will result in either a business standstill for a whole month or a 33% decline during three months. This discovery of active destocking and the Lehman wave can have important implications for manufacturing scheduling, inventory management, work force management and budgeting.[5]

Relation with the Lehman wave and bullwhip effect

While the existence of the bullwhip effect has been extensively documented (e.g., Forrester (1961),[6] Sterman (1989),[7] and Lee et al. (1997),[8] Croson and Donohue (2006)[9]), there have been arguments about its existence in the overall economy or in supply chains encompassing numerous companies. Cachon et al. (2007)[10] recently argued that no evidence of the existence of the bullwhip effect could be found. Fransoo and Wouters (2000)[11] and Chen and Lee (2009)[12] argue that in order to observe the bullwhip effect it is crucial to measure it correctly. Both these papers argue that improper aggregation essentially takes away the opportunity to observe the bullwhip effect. In the beer distribution game (Sterman, 1989[7]), the bullwhip effect is created by a single pulse. In Sterman's experiment, this single pulse is an increase in the demand level. In the case of the Lehman wave that started in September 2008, the single pulse is active destocking, in this case a synchronized decrease in the target inventory-over-sales level along the entire supply chain. A reduction of inventories under stable or slightly decreasing sales can only be achieved if purchases are reduced or postponed. As a consequence of the decision to reduce inventory, therefore, many companies substantially reduced their purchases of supplies or raw materials. Obviously, companies further upstream in the supply chain were hit more than companies downstream. Therefore, the Lehman wave can be described as a synchronized bullwhip caused by active destocking, deepened by reactive destocking.

References

- 1 2 "Managing and Accounting for Your Inventory | BizFilings Toolkit". Toolkit.com. Retrieved 2012-08-22.

- ↑ "/ Companies / European companies - 'Lehman wave' set to help track recovery". Ft.com. 2009-12-22. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- ↑ "Responding to the Lehman Wave: Sales Forecasting and Supply Management during the Credit Crisis | Beta". Beta.ieis.tue.nl. 2009-12-07. Archived from the original on 2012-03-07. Retrieved 2012-08-22.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "European-coatings.com". European-coatings.com. Retrieved 2012-08-22.

- ↑ "Lehman Wave". Financecareers.about.com. 2012-08-01. Archived from the original on 2012-11-18. Retrieved 2012-08-22.

- ↑ Forrester, J.W. (1961), Industrial Dynamics. Cambridge: MIT Press, and New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- 1 2 Sterman, J.D. (1989), Modeling Managerial Behavior: Misperceptions of Feedback in a Dynamic Decision Making Experiment, Management Science 35:3, 321-339.

- ↑ Lee, H.L., V. Padmanabhan, and S. Whang (1997), Information Distortion in a Supply Chain: The Bullwhip Effect, Management Science, 43:4, 546-558.

- ↑ Croson, R., and K. Donohue (2006), Behavioral causes of the bullwhip effect and the observed value of inventory information, Management Science, 52:3, 323-336.

- ↑ Cachon, G.P., T. Randall, and G.M. Schmidt (2007), In Search of the Bullwhip Effect, Manufacturing & Service Operations Management 9:4, 457-479.

- ↑ Fransoo, J.C., and M.J.F. Wouters (2000), Measuring the bullwhip effect in the supply chain, Supply Chain Management 5:2, 78-89

- ↑ Chen, L., and H.L. Lee (2009), Information Sharing and Order Variability Control Under a Generalized Demand Model, Management Science 55:5, 781-797.