Acuera was the name of both an indigenous town and a province or region in central Florida during the 16th and 17th centuries. The indigenous people of Acuera spoke a dialect of the Timucua language. In 1539 the town first encountered Europeans when it was raided by soldiers of Hernando de Soto's expedition. French colonists also knew this town during their brief tenure (1564–1565) in northern Florida.

Late in the 16th century, Acuera came under Spanish influence as it expanded its settlements. Two or three Spanish missions were founded in the Acuera province in the 17th century.

Location

Based on distances between indigenous towns reported by Spanish explorers, anthropologists Jerald T. Milanich and Charles Hudson locate the town of Acuera in central Florida near Lake Weir and Lake Griffin, near the headwaters of the Oklawaha River, a tributary of the St. Johns River. A map produced by Jacques le Moyne, who was part of the late 16th-century French attempt to colonize Florida at Fort Caroline, shows a town called Aquouena (Acuera?) east of Eloquale (Ocale), on a tributary of the St. Johns River. The French also recorded a chief named Acquera being a vassal of Chief Utina.

The 17th-century Spanish missions of San Luis de Acuera and Santa Lucia de Acuera were reported to be at distances from St. Augustine that are consistent with the missions being located near the Oklawaha River and Lake Weir.

In 1836 Lake Weir was identified on an Anglo-American map as "Lake Ware." Milanich and Hudson speculate that "Ware" was derived from "Acuera". Boyer has identified the Hutto/Martin Site, 8MR3447, a little to the north of Lake Weir, as being the site of the 17th-century mission of Santa Lucia de Acuera and the likely site of the town of Acuera recorded in the Ranjel account of the Hernando de Soto entrada.[1]

The territory occupied by the Acuera people in historical times was part of the St. Johns culture. It is characterized by the people's creating shell middens from their refuse, and burial mounds for their dead. They made a "chalky" pottery based on the use of freshwater sponge spicules as a temper, sometimes decorated with check-stamping.[2][3][4][5][6]

Language

"Santa Lucia de Acuera" was one of nine or ten dialects of the Timucua language named by the Franciscan missionary Francisco Pareja in the early 17th century. Pareja regarded the Santa Lucia de Acuera and Tucururu (which may have adjoined Acuera) dialects as the most divergent from what he considered the standard dialect, that of Mocama.[7][8]

Political organization

The province of Acuera may have consisted of several small chiefdoms, including Avino, Eloquale, and Acuera. Utiaca may have been under the chief of Avino, while Piliuco, and possibly Mocoso, were towns under the chief of Acuera. Tucuru may have been under Avino, or may have been independent. The caciques (chiefs) of Tucuru and Eloquale visited St. Augustine earlier than the cacica (female chief) of Acuera did.

Eloquale, a town on the Oklawaha River, may have been a new location for the town of Ocale, which was near the Withlacoochee River when the de Soto expedition stopped there for two weeks in 1539.[9][10] Ocale was also referred to as Cale and Etocale by Spanish chroniclers of the de Soto expedition. After the de Soto expedition stayed in 1539 at the town of Mocoso on Tampa Bay, it may have been relocated to the province of Acuera.[11][12]

European contact

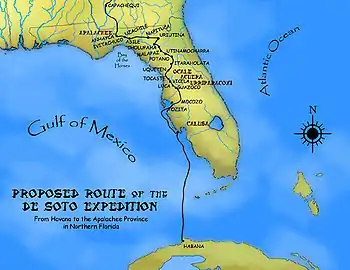

In 1539 Hernando de Soto landed in Tampa Bay with more than 600 men and 200 horses. The expedition intended to live off the land, taking food stored in the towns along their path. De Soto received a report of a large town named Acuera, said to have abundant maize. De Soto's main forces moved north from Tampa Bay to Ocale, where they stopped for two weeks. While at Ocale, de Soto twice sent soldiers to seize maize from Acuera. The Acuera strongly resisted the Spanish incursions. Garcilaso de la Vega, known as El Inca, in his later romanticized and somewhat less than reliable history of the de Soto expedition, portrayed the Acuera as proud and fierce warriors.[13][14][15][16]

With the establishment of Fort Caroline in 1564 by French Huguenots near the mouth of the St. Johns River, the Acuera, along with most other Timucua speakers, came into continuing contact with Europeans. The Spanish drove the French out of Florida the next year and established St. Augustine. During this period the Acuera chiefdom was subject to or associated with the Utina chiefdom, but became independent of Utina as that chiefdom declined in power.

The cacica (female chief) of Acuera went to St. Augustine in 1597 to render obedience to Spain. Most of the other Timucua chiefdoms had also done so by this time, and had requested missionaries be sent to their provinces. However, a rebellion in Guale that occurred shortly before the Acuera submission to Spain resulted in almost all missionaries being withdrawn from Spanish Florida. Acuera sent laborers to St. Augustine during the period from 1597 to 1602. People from Acuera also went to St. Augustine to trade deer skins, chestnuts, and pots.[17][18][19]

Missions

The mission of San Blas de Habino was established after 1610 to serve the towns of Avino, Tucuru and Utiaca, which were on the lower to middle Oklawaha River, at intervals of one-and-a-half to two leagues apart.[20][21] The Spanish may have regarded this area as part of the Acuera province, or Avino may have been an alternate name for Acuera. The mission of San Blas de Habino probably was abandoned by the late 1620s.

The mission of Santa Lucia de Acuera was established by 1627, when Father Pareja named one of the dialects of the Timucua language after the mission. The mission of San Luis de Eloquale[Footnote 1] was noted in a Spanish report in 1630. Both missions may have been established by the 1620s. No missions in Acuera province appear in Spanish records after the Timucuan Rebellion of 1656, but the Acuera appear to have remained in their traditional territory throughout the rest of the seventeenth century.[22][23]

In the late 1620s the Spanish resettled the indigenous people of Utiaca at the mission of San Diego de Helaca (or Laca) on the east side of the St. Johns River, where the route from St. Augustine to the western Timucuan missions crossed the river.[Footnote 2] They were probably needed there to serve the river crossing, as the original inhabitants, the Agua Dulce people, were greatly reduced in numbers. Epidemics of new infectious diseases, which were endemic among the Europeans, caused high mortality rates and severely affected Timucua mission communities in the 1650s. Following the Timucua rebellion of 1656, the Spanish consolidated missions closer to the road connecting St. Augustine to the Apalachee Province. Their efforts to maintain missions in Acuera province stopped after the 1656 rebellion.

Even at the height of the Spanish founding missions in Acuera province, the Acuera were virtually unique among the Timucua peoples in that they appear to have created a "parallel" system of religious authority to that of the missionaries. Their traditional religious leaders, who had substantial followings, openly practiced their beliefs.[24][25] Historical and recent archaeological evidence suggests that conversion to Catholicism may have been limited to either the chiefly class or to refugees from other Timucuan groups forced into missions.[26][27][28]

After the Timucuan Rebellion in 1656, the Acuera seem to have either defied or not been subject to the order of Spanish governor Diego de Rebolledo to consolidate along the Camino Real.[29][30] During the latter half of the seventeenth century, Spanish records indicate the Acuera maintained a traditional religious and political system, with multiple towns and villages.[31] Calesa, nephew of the Acuera chief Jabahica, was tried in 1678 by the Governor of Florida for multiple murders (he was accused of six, and admitted in court to three). Boyer has argued that these killings had a religious and social significance to the Acuera.[32] The Acuera last appeared in Spanish records in 1697, in a report that (non-Christian) Acuera living in a village with the Ayapaja, under a single chief, had left the village to "live in the woods".[33][34][35][36]

The indigenous people living in mission villages along the road between St. Augustine and the western Timucuan provinces, and later, Apalachee Province, were subject to labor drafts. Workers were required to carry produce from the western Timucuam provinces and Apalachee to St. Augustine, and also to work in the town of St. Augustine. Residents of those villages, escaping such labor duties, fled southward into the Acuera, Agua Dulce and Mayaca provinces (by the 1640s the Spanish referred to those provinces as a group as the Diminiyuti or Ibiniyuti Province [ibiniuti was Timucuan for "water land"]). In 1648, the cacique of the Utiaca fled with part of his people from San Diege de Helaca and returned to Acuera Province.[37][38]

Footnotes

- ↑ "Eloquale" may be an alternate form of "Ocale" or "Etocale". The town of Ocale was located near the Withlacoochee River when it was visited by Hernando de Soto in 1539, but may have been moved to the Oklawaha River by the early 17th century. It was located about two leagues from the mission of Santa Lucia de Acuera. The town of Mocoso, located on Tampa Bay when it was visited by de Soto in 1539, may have also been relocated to Acuera Territory.(Hann: 135. Worth 1: 71, 95.)

- ↑ The mission village of San Diego was apparently moved sometime before 1689 to the nearby site of Salamototo. The mission village of San Diego, both at Helaca and at Salamototo, was populated with people moved from abandoned missions in Acuera, Agua Dulce and Mayaca provinces.(Worth 2: 100)

See also

References

- ↑ Boyer,III, Willet. "The Hutto/Martin Site of Marion County, Florida, 8MR3447: Studies at an Early Contact/Mission Site". The Florida Anthropologist Volume 70(3:122-139) 2017.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) On-line as "The Hutto/Martin Site of Marion County, Florida, 8MR3447: Studies at an Early Contact/Mission Site". academia.edu. 7 December 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2017. - ↑ Boyer 2009: 47

- ↑ Hann 1996: 12, 13

- ↑ Milanich and Hudson: 94, 96, 131

- ↑ Milanich 1995: 82, 170, 176

- ↑ Boyer 2010

- ↑ Hann 1996: 6, 12

- ↑ Milanich 1995: 82

- ↑ Boyer, Willet A. III (2009). "Missions to the Acuera: An Analysis of the Historic and Archaeological Evidence for European Interaction With a Timucuan Chiefdom". The Florida Anthropologist. 62 (1–2): 45–56. ISSN 0015-3893. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- ↑ Boyer, Willet A. III (2010). The Acuera of the Oklawaha River Valley: Keepers of Time in the Land of the Waters (PDF) (dissertation). University of Florida. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ↑ Hann 2003: 135

- ↑ Worth 1: 65, 66, 95

- ↑ Boyer 2009: 46

- ↑ Hann 1996: 12

- ↑ Milanich and Hudson: 71-73, 81-87, 96, 133

- ↑ Milanich 1995: 132

- ↑ Hann 1996: 147, 163

- ↑ Milanich 1995: 89

- ↑ Worth 1: 22, 25, 50, 52, 54

- ↑ Boyer 2009

- ↑ Boyer 2010

- ↑ Boyer 2009

- ↑ Boyer 2010

- ↑ Boyer 2009

- ↑ Boyer 2010

- ↑ Boyer 2009

- ↑ Boyer 2010

- ↑ Boyer 2017

- ↑ Worth 2

- ↑ Boyer 2010

- ↑ Boyer 2010

- ↑ Boyer 2010

- ↑ Boyer 2009: 46, 47, 49

- ↑ Hann 1996: 13, 174, 178, 190-91, 240-41, 244

- ↑ Worth 1: 63, 65, 69, 71

- ↑ Worth 2: 31-32

- ↑ Milanich 1995: 170

- ↑ Worth 2: 25, 31, 32, 100

Works cited

- Boyer, Willet A. III (2009). "Missions to the Acuera: An Analysis of the Historic and Archaeological Evidence for European Interaction With a Timucuan Chiefdom". The Florida Anthropologist. 62 (1–2): 45–56. ISSN 0015-3893. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- Boyer, Willet A. III (2010). The Acuera of the Oklawaha River Valley: Keepers of Time in the Land of the Waters (PDF) (dissertation). University of Florida. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- Boyer, Willet A. (2017) Boyer,III, Willet. "The Hutto/Martin Site of Marion County, Florida, 8MR3447: Studies at an Early Contact/Mission Site". The Florida Anthropologist Volume 70(3:122-139) 2017.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) On-line as "The Hutto/Martin Site of Marion County, Florida, 8MR3447: Studies at an Early Contact/Mission Site". academia.edu. 7 December 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2017. - Hann, John H. (1996). A History of the Timucua Indians and Missions. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1424-7.

- Hann, John H. (2003). Indians of Central and South Florida 1513-1763. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2645-8.

- Milanich, Jerald T., Charles Hudson (1993). Hernando de Soto and the Indians of Florida. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1170-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Milanich, Jerald T. (1995). Florida Indians and the Invasion from Europe. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1636-3.

- Oppermann, Michael (February 16, 2009). "Searching for a mission". Ocala Star-Banner. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- Worth, John E. (1998). Timucuan Chiefdoms of Spanish Florida Volume 1 Assimilation. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1574-X.

- Worth, John E. (1998). Timucuan Chiefdoms of Spanish Florida Volume 2 Resistance and Destruction. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1575-8.