The Duke of Suárez | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Suárez in 1979 | |

| Prime Minister of Spain | |

| In office 5 July 1976 – 26 February 1981 | |

| Monarch | Juan Carlos I |

| Deputy | Manuel Gutiérrez Mellado |

| Preceded by | Fernando de Santiago (Acting) |

| Succeeded by | Leopoldo Calvo Sotelo |

| President of the Liberal International | |

| In office 26 April 1989 – 22 April 1992 | |

| Preceded by | Giovanni Malagodi |

| Succeeded by | Otto Graf Lambsdorff |

| President of the Democratic and Social Centre | |

| In office 2 October 1982 – 26 May 1991 | |

| Preceded by | Party established |

| Succeeded by | Rafael Calvo Ortega |

| President of the Union of the Democratic Centre | |

| In office 21 October 1978 – 9 February 1981 | |

| Preceded by | Party established |

| Succeeded by | Agustín Rodríguez Sahagún |

| Minister-Secretary General of the Movimiento Nacional | |

| In office 12 December 1975 – 6 July 1976 | |

| Preceded by | Ignacio García López |

| Succeeded by | José Solís Ruiz |

| Deputy Secretary General of the Movimiento Nacional | |

| In office 21 March 1975 – 2 July 1975 | |

| Preceded by | Antonio García Rodríguez-Acosta |

| Succeeded by | Antonio Chozas Bermúdez |

| Director General of RTVE | |

| In office 14 May 1969 – 25 June 1973 | |

| Preceded by | Jesús Aparicio-Bernal |

| Succeeded by | Rafael Orbe |

| Civil Governor of the Province of Segovia | |

| In office 31 May 1968 – 7 November 1969 | |

| Preceded by | Juan Murillo de Valdivia |

| Succeeded by | Mariano Pérez-Hickman |

| Member of the Congress of Deputies | |

| In office 22 July 1977 – 26 October 1991 | |

| Constituency | Madrid |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Adolfo Suárez González 25 September 1932 Cebreros, Ávila, Second Spanish Republic |

| Died | 23 March 2014 (aged 81) Madrid, Spain |

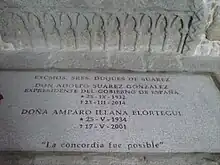

| Resting place | Cathedral of Ávila |

| Political party | Democratic and Social Centre (1982–1991) |

| Other political affiliations | FET y de las JONS (1958–1977) Union of the Democratic Centre (1977–1982) |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 5 including Adolfo |

| Parent(s) | Hipólito Suárez Guerra Herminia González Prados |

| Alma mater | Salamanca University |

| Occupation | Jurist |

| Signature | |

Adolfo Suárez González, 1st Duke of Suárez (Spanish pronunciation: [aˈðolfo ˈswaɾeθ]; 25 September 1932 – 23 March 2014) was a Spanish lawyer and politician. Suárez was Spain's first democratically elected prime minister since the Second Spanish Republic and a key figure in the country's transition to democracy after the dictatorship of Francisco Franco.

When Spain was still an autocratic regime, he was appointed prime minister by King Juan Carlos in 1976, hoping that his government could bring about democracy. At the time of his appointment, he was not a well-known figure, making many political forces skeptical of his government. However, he oversaw the end of the Francoist Cortes, and the legalisation of all political parties (including the Communist Party of Spain, a particularly difficult move). He led the Union of the Democratic Centre and won the 1977 general election. In 1981, he resigned and founded the party Democratic and Social Centre (CDS), which was elected to the Cortes numerous times. He retired from politics in 1991 and from public life in 2003, due to Alzheimer's disease.

Early life

Adolfo Suárez González was born on 25 September 1932 in Cebreros in the Province of Ávila of Spain,[1] the eldest son of Hipólito Suárez Guerra, a lawyer, and Herminia González Prados.[2][3][4] Both of his parents supported the Republicans during the Spanish Civil War.[5] At the age of 18, Suárez was president of the Ávila chapter of Catholic Action.[1] He studied law at the University of Salamanca, after which he took a job at the municipal government of Ávila in 1955. He subsequently became a member of Opus Dei, and obtained a doctorate at the Central University of Madrid.[6][7] He also worked briefly as a porter at Madrid's Atocha railway station.[1]

Political career

Early career

In 1958, Suárez became the personal secretary of Fernando Herrero Tejedor, the newly appointed civil governor of Ávila. When Tejedor was made deputy secretary-general of the Movimiento Nacional in 1961, Suárez became his chef de cabinet.[1][2][6] He gradually rose through the ranks of the Movimiento. In 1965, Suárez was appointed programme director of the state broadcaster Radio y Televisión Española (RTVE). In 1967, he was elected to the Francoist Cortes.[6] In 1968, Suárez was promoted to civil governor and provincial head of the Movimiento in Segovia.[7] In 1969, he was made director general of RTVE. Under this capacity, he became a close friend to future king Prince Juan Carlos.[1][6]

In March 1975, Herrero Tejedor became secretary-general of the Movimiento while Suárez was appointed deputy secretary-general. Herrero Tejedor was considered a likely candidate for prime minister until his death in a car accident in June.[1] In December, shortly after Francisco Franco's death, Suárez was promoted to secretary-general by prime minister Carlos Arias Navarro, and became a member of Arias's cabinet. In the same year, he also became a founding member of the Spanish People's Union (Unión del Pueblo Español, UDPE).[7]

Premiership

In July 1976, King Juan Carlos requested the resignation of Arias. The relatively obscure Suárez was chosen as the new Prime Minister of Spain, surprising many observers.[6] At the age of 43, he was Spain's youngest prime minister in the 20th century.[7] Due to his Francoist ties, Suárez enjoyed the trust of the political right, while the reformists were dismayed by his appointment.[8][9] Nevertheless, it was noted that due to his age (he turned 7 years old in the year the civil war ended), Suárez was not as strongly associated with the bloody Civil War or the most brutal years of Franco's rule as the older politicians.[2][8]

Within a year of his appointment, Suárez had rapidly introduced reform measures and taken decisive steps in Spain's transition to democracy (La Transición). The Political Reform Act, which permitted universal suffrage and established the basis for a new, bicameral parliament, was passed by a huge majority in the Francoist Cortes in November 1976 and overwhelmingly approved by a referendum in December.[6][9] Suárez managed to placate the conservative military officers, while also reaching out to Felipe González's Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) and later, Santiago Carrillo's Communist Party of Spain (PCE).[6] Between February and April 1977, the PSOE and the PCE were both legalised, trade unions were recognised, and the Movimiento was abolished.[9] The legalisation of the PCE in particular provoked fury in the Spanish military; Suárez responded by sacking hardliners and promoting more liberal officers such as Manuel Gutiérrez Mellado.[5] On 15 June, Suárez led the Union of the Democratic Centre (Unión de Centro Democrático, UCD) to victory in Spain's first free elections in 41 years, and became the first democratically elected prime minister of the post-Francoist Spain.[9]

Suárez's centrist government instituted further democratic reforms. A new constitution, which recognised Spain as a constitutional monarchy, was approved by a referendum in December 1978.[9] In an effort to address separatist tensions and calls for increased local autonomy, Suárez also negotiated the creation of Spain's autonomous communities. Suárez's coalition won the 1979 elections under the new constitution.[6]

Suárez's political power eroded as he struggled to deal with economic recession, mounting violent activity by ETA, calls for further regional autonomy and divisions within his own party. He became increasingly withdrawn from governance, partly due to a chronic dental condition. He survived a motion of no confidence presented by Felipe González and the PSOE in May 1980.[6] In January 1981, trailing in the polls behind the PSOE and faced with a revolt within the UCD, Suárez announced his resignation as prime minister.[2] A month later, as parliament took the vote to confirm Suárez's successor Leopoldo Calvo-Sotelo, Lieutenant-Colonel Antonio Tejero and around 200 Civil Guards stormed the chamber in an attempted coup and held the lawmakers hostage for some 22 hours.[7] Suárez, along with two other parliamentarians, exhibited defiance by remaining calmly seated during the panic.[6] The 23-F coup attempt ("El Tejerazo") failed as it was opposed by Spain's main newspaper El País (who managed to get a special edition in favor of the constitution issued and distributed on the evening of the coup attempt) and denounced by King Juan Carlos I in a televised address. Meanwhile promised military support for the coup failed to materialise – with few exceptions, most notably Jaime Milans del Bosch who led pro-coup troops in Valencia.[7]

Post-premiership

In 1982, Suárez founded the Democratic and Social Centre (Centro Democrático y Social, CDS) party, which never achieved the success of UCD, though Suárez and its party were important elements in the Liberal International, joining it in 1988, leading to it being renamed Liberal and Progressive International, and Suárez became President of the Liberal International in 1988.[10] He retired from active politics in 1991, for personal reasons.[6]

In 1981, Suárez was raised into the Spanish nobility by King Juan Carlos of Spain and given the hereditary title of "Duque de Suárez" (Duke of Suárez), together with the title Grande de España (English: Grandee of Spain) following his resignation as Prime Minister and in recognition of his role in the transition to democracy. Suárez was awarded the Príncipe de Asturias a la Concordia in September 1996 for his role in Spain's early democracy. On 8 June 2007, during the celebration of the 30th anniversary of the first democratic elections, King Juan Carlos appointed Suárez the 1,193rd Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece.[11] He was also a member of the Club de Madrid, an independent organization (based in Madrid) that is composed of more than 80 former democratic Prime Ministers and Presidents. The group works to strengthen democratic governance and leadership.[12]

Illness and death

On 31 May 2005, Suárez's son, Adolfo Suárez Illana, announced on Spanish television that his father was suffering from Alzheimer's disease. The announcement followed speculation about Suárez's health in the Spanish media. On 21 March 2014, his son announced that his death from neurological deterioration was imminent.[13] Suárez then died as a result of a respiratory infection on 23 March 2014 in a clinic in Madrid.[14] Suarez was given a state funeral and was buried in the cloister of Ávila Cathedral.[15]

Pope Francis shared his condolences, saying: "In fraternal suffrage with you all, I make fervent prayers to the Lord for the eternal rest of this esteemed and feature figure of the recent history of Spain."[16]

On 26 March 2014, the Spanish government decided to rename the Madrid-Barajas Airport to Adolfo Suárez Madrid–Barajas Airport in honour of his service to the country.[17]

Family

Suárez married María del Amparo Illana Elórtegui in 1961. She died from cancer on 17 May 2001.[18] Their eldest daughter, María del Amparo ("Mariam") Suárez Illana (1962–2004), died of breast cancer on 6 March 2004, following an 11-year illness.[19] Both of her younger sisters also suffered from the same illness.[20] She was the mother of two children, Alejandra Romero Suárez (born 1990), herself the current holder of her grandfather's dukedom, and Fernando Romero Suárez (born 1993).[19]

Suarez' youngest daughter, María Sonsoles Suárez Illana (born 1967), became a TV news anchor for Antena 3. From 1992 to 1994 she was married to José María Martínez-Bordiú y Bassó de Roviralta (a nephew of Cristóbal Martínez-Bordiú, the son-in-law of Francisco Franco); the couple was without issue. In 2012 she married the Mozambican musician Paulo Wilson, and they separated in 2017.[20]

Suárez's eldest son, Adolfo Suárez Illana, is a politician, lawyer, and is heavily involved with the world of bullfighting and has two sons. Suárez had two more children, his daughter Laura and his son Francisco Javier; both remain unmarried.

Honours

Decorations

National

Spain

Spain

1,193rd Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece (8 June 2007).[21]

1,193rd Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece (8 June 2007).[21] Collar of the Order of Charles III (Posthumously) (24 March 2014).[22]

Collar of the Order of Charles III (Posthumously) (24 March 2014).[22] Grand Cross of the Order of Charles III (23 June 1978).[23]

Grand Cross of the Order of Charles III (23 June 1978).[23] Grand Cross of the Order of Isabella the Catholic (29 September 1973).[24]

Grand Cross of the Order of Isabella the Catholic (29 September 1973).[24]_GC.svg.png.webp) Grand Cross of the Order of Civil Merit (18 July 1969).[25]

Grand Cross of the Order of Civil Merit (18 July 1969).[25] Grand Cross of the Civil Order of Alfonso X, the Wise (1 April 1970).[26]

Grand Cross of the Civil Order of Alfonso X, the Wise (1 April 1970).[26] Commander's Cross of the Civil Order of Alfonso X, the Wise (1 April 1967).[27]

Commander's Cross of the Civil Order of Alfonso X, the Wise (1 April 1967).[27]_pasador.svg.png.webp) Grand Cross of the Order of Naval Merit (1 April 1972).[28]

Grand Cross of the Order of Naval Merit (1 April 1972).[28] Grand Cross of the Order of Cisneros (18 July 1972).[29]

Grand Cross of the Order of Cisneros (18 July 1972).[29] Grand Cross of the Order of the Yoke and the Arrows (4 July 1975).[30]

Grand Cross of the Order of the Yoke and the Arrows (4 July 1975).[30]_pasador.svg.png.webp) Grand Cross of the Military Merit with White Decoration (14 September 1970).[31]

Grand Cross of the Military Merit with White Decoration (14 September 1970).[31]

Foreign

Portugal:

Portugal:

Grand Cross of the Order of Christ (20 April 1978).[32]

Grand Cross of the Order of Christ (20 April 1978).[32] Grand Cross of the Order of Liberty (22 February 1996).[32]

Grand Cross of the Order of Liberty (22 February 1996).[32]

Awards

- Gold Medal of Segovia (17 November 1969).[33]

- Gold Medal of Ávila (12 February 1981). Received on 9 June 2005.[34]

- Adopted Son of Ávila (12 February 1981). Received on 9 June 2005.[34]

- Alfonso X the Wise International Prize in Toledo (21 October 1994).[35]

- Gold Medal of Madrid (30 November 1995). Received on 10 November 1998.[36][37]

- Honorary Degree by the Complutense University of Madrid (28 May 1996).[38]

- Prince of Asturias Concord Award (13 September 1996).[39]

- Coexistence Award of Ceuta (30 April 1999).[40][41]

- Gold Medal of Castilla y León (22 March 1997).[42]

- Medal of Honor of Madrid (15 May 2011).[43]

- Adopted Son of Madrid (Posthumous, 27 March 2014).[44]

Arms

|

Coat of arms bore as knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece. |

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Spain's Election Victor". The New York Times. 17 June 1977. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Minder, Raphael (23 March 2014). "Adolfo Suárez Dies at 81; Led Spain Back to Democracy". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ↑ Fernández, Carlos (25 February 2005). "Republicano y padre de presidente". La Voz de Galicia (in Spanish). Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ↑ Garcia Abad, José (23 July 2006). "LA MUJER QUE HIZO A SUÁREZ". El Mundo (in Spanish). Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- 1 2 "Spain's democracy man". The Economist. 29 March 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Preston, Paul (23 March 2014). "Adolfo Suárez obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Adolfo Suárez - obituary". The Telegraph. 23 March 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- 1 2 Langer, Emily (23 March 2014). "Adolfo Suarez, former Spanish prime minister, dies at 81". The Washington Post. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fotheringham, Alasdair (23 March 2014). "Adolfo Suarez: Spain's first democratically elected Prime Minister who oversaw the transition from the country's Franco years". The Independent. Archived from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ↑ Roberts, Geoffrey K.; Hogwood, Patricia (2003), The Politics Today companion to West European politics, Manchester University Press, p. 137

- ↑ BOE 07-06-09, Spanish official journal. Retrieved 9 June 2007.

- ↑ "Suárez, Adolfo". World Leadership Alliance. Archived from the original on 23 March 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ↑ Cué, Francesco Manetto, Carlos E. (21 March 2014). "El hijo de Adolfo Suárez sobre su padre: "El desenlace es inminente"". El País. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Fallece Adolfo Suárez, el presidente de la Transición, El Mundo, 23 March 2014

- ↑ "Adolfo Suárez reposa ya en Ávila bajo el epitafio 'La concordia fue posible'". El Mundo (in Spanish). EFE. 26 March 2014. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- ↑ "Telegrama de pésame del Papa Francisco por la muerte de Adolfo Suárez". Revista Ecclesia (in Spanish). 27 March 2014. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- ↑ "El aeropuerto de Madrid se llama desde hoy Adolfo Suárez". El Mundo (in Spanish). 24 March 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ↑ "Fallece Amparo Illana, esposa de Adolfo Suárez". El País. 18 May 2001.

- 1 2 "Mariam Suárez, una luchadora contra el cáncer". El País (in Spanish). 7 March 2004. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- 1 2 "Sonsoles Suárez, la hija del expresidente Adolfo Suárez, se separa de su marido Paulo Wilson". El País (in Spanish). 10 November 2017. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- ↑ "Boletín Oficial del Estado 07-06-09, Spanish Official Journal" (PDF). Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ "Boletín Oficial del Estado 14-03-24, Spanish Official Journal" (PDF). Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ Boletín Oficial del Estado 78-06-23, Spanish Official Journal (accessed on 23 December 2011)

- ↑ Spanish: Boletín Oficial del Estado 73-09-29, Spanish Official Journal (accessed on 23 December 2011)

- ↑ Spanish: Boletín Oficial del Estado 69-07-18, Spanish Official Journal (accessed on 23 December 2011)

- ↑ Spanish: Boletín Oficial del Estado 71-04-05, Spanish Official Journal (accessed on 23 December 2011)

- ↑ Spanish: Boletín Oficial del Estado 67-04-01, Spanish Official Journal (accessed on 23 December 2011)

- ↑ Spanish: Boletín Oficial del Estado 72-04-01, Spanish Official Journal (accessed on 24 March 2014)

- ↑ Spanish: Boletín Oficial del Estado 72-07-18, Spanish Official Journal (accessed on 23 December 2011)

- ↑ Spanish: Boletín Oficial del Estado 75-07-04, Spanish Official Journal (accessed on 23 December 2011)

- ↑ Spanish: Boletín Oficial del Estado 70-09-15, Spanish Official Journal (accessed on 23 December 2011)

- 1 2 "CIDADÃOS ESTRANGEIROS AGRACIADOS COM ORDENS PORTUGUESAS – Página Oficial das Ordens Honoríficas Portuguesas". www.ordens.presidencia.pt. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ Medalla de Oro de la provincia de Segovia concedida a su Alteza Real Don Juan de Borbón y Battenberg (1991). Segovia. Provincial Council of Segovia. ISBN 84-86789-35-4.

- 1 2 Ávila, Diario de (24 March 2014). "La "deuda histórica" de Ávila a Suárez". Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ "Adolfo Suárez 1932 – 2014". El País. 27 January 2017. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ "ABC (Madrid) – 12/11/1998, p. 71 – ABC.es Hemeroteca". hemeroteca.abc.es. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ "ABC (Madrid) – 01/12/1995, p. 12 – ABC.es Hemeroteca". hemeroteca.abc.es. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ "Adolfo Suárez 1932 – 2014". El País. 27 January 2017. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ Cuartas, Javier (14 September 1996). "Adolfo Suárez premio Príncipe de Asturias por su aportación a la "concordia democrática"". El País. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ "Con Adolfo Suárez se va el primer galardonado por la Fundación Premio Convivencia". Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ "Suárez, González y Roca hablarán de "España desde la Constitución"". El País. 30 April 1999. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ "Adolfo Suárez, profeta en su tierra". www.leonoticias.com. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ "Adolfo Suárez recibirá la Medalla de Honor de Madrid y Aznar y González la de oro". Europa Press. 30 March 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ "El Pleno municipal designa a Adolfo Suárez como Hijo Adoptivo". Europa Press. 27 March 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ (in Spanish) Adolfo Suárez, AMPA Súarez, p. 5 . Retrieved 24 March 2014.

External links

- Biography by CIDOB Archived 31 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish)

- Tribute to Adolfo Suárez: Guestbook