| Spanish Civil War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the interwar period | |||||||

Clockwise from top-left: Members of the XI International Brigade at the Battle of Belchite; Granollers after being bombed by the Aviazione Legionaria in 1938; Bombing of an airfield in Spanish Morocco; Republican soldiers at the siege of the Alcázar; Nationalist soldiers operating an anti-aircraft gun; The Lincoln Battalion | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

1936 strength:[1]

–1,546 Canadians

|

1936 strength:[4]

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| c. 400,000–450,000 total killed[note 1] | |||||||

| History of Spain |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

- Treaty of Versailles 1919

- Polish–Soviet War 1919

- Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye 1919

- Treaty of Trianon 1920

- Treaty of Rapallo 1920

- Franco-Polish alliance 1921

- March on Rome 1922

- Corfu incident 1923

- Occupation of the Ruhr 1923–1925

- Mein Kampf 1925

- Second Italo-Senussi War 1923–1932

- Dawes Plan 1924

- Locarno Treaties 1925

- Young Plan 1929

- Great Depression 1929

- Japanese invasion of Manchuria 1931

- Pacification of Manchukuo 1931–1942

- January 28 incident 1932

- Geneva Conference 1932–1934

- Defense of the Great Wall 1933

- Battle of Rehe 1933

- Nazis' rise to power in Germany 1933

- Tanggu Truce 1933

- Italo-Soviet Pact 1933

- Inner Mongolian Campaign 1933–1936

- German–Polish declaration of non-aggression 1934

- Franco-Soviet Treaty of Mutual Assistance 1935

- Soviet–Czechoslovakia Treaty of Mutual Assistance 1935

- He–Umezu Agreement 1935

- Anglo-German Naval Agreement 1935

- December 9th Movement

- Second Italo-Ethiopian War 1935–1936

- Remilitarization of the Rhineland 1936

- Spanish Civil War 1936–1939

- Italo-German "Axis" protocol 1936

- Anti-Comintern Pact 1936

- Suiyuan campaign 1936

- Xi'an Incident 1936

- Second Sino-Japanese War 1937–1945

- USS Panay incident 1937

- Anschluss Mar. 1938

- May Crisis May 1938

- Battle of Lake Khasan July–Aug. 1938

- Bled Agreement Aug. 1938

- Undeclared German–Czechoslovak War Sep. 1938

- Munich Agreement Sep. 1938

- First Vienna Award Nov. 1938

- German occupation of Czechoslovakia Mar. 1939

- Hungarian invasion of Carpatho-Ukraine Mar. 1939

- German ultimatum to Lithuania Mar. 1939

- Slovak–Hungarian War Mar. 1939

- Final offensive of the Spanish Civil War Mar.–Apr. 1939

- Danzig Crisis Mar.–Aug. 1939

- British guarantee to Poland Mar. 1939

- Italian invasion of Albania Apr. 1939

- Soviet–British–French Moscow negotiations Apr.–Aug. 1939

- Pact of Steel May 1939

- Battles of Khalkhin Gol May–Sep. 1939

- Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact Aug. 1939

- Invasion of Poland Sep. 1939

The Spanish Civil War (Spanish: Guerra Civil Española)[note 2] was fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republicans and the Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the left-leaning Popular Front government of the Second Spanish Republic, and consisted of various socialist, communist, separatist, anarchist, and republican parties, some of which had opposed the government in the pre-war period.[10] The opposing Nationalists were an alliance of Falangists, monarchists, conservatives, and traditionalists led by a military junta among whom General Francisco Franco quickly achieved a preponderant role. Due to the international political climate at the time, the war had many facets and was variously viewed as class struggle, a religious struggle, a struggle between dictatorship and republican democracy, between revolution and counterrevolution, and between fascism and communism.[11] According to Claude Bowers, U.S. ambassador to Spain during the war, it was the "dress rehearsal" for World War II.[12] The Nationalists won the war, which ended in early 1939, and ruled Spain until Franco's death in November 1975.

The war began after the partial failure of the coup d'état of July 1936 against the Republican government by a group of generals of the Spanish Republican Armed Forces, with General Emilio Mola as the primary planner and leader and having General José Sanjurjo as a figurehead. The government at the time was a coalition of Republicans, supported in the Cortes by communist and socialist parties, under the leadership of centre-left President Manuel Azaña.[13][14] The Nationalist faction was supported by a number of conservative groups, including CEDA, monarchists, including both the opposing Alfonsists and the religious conservative Carlists, and the Falange Española de las JONS, a fascist political party.[15] After the deaths of Sanjurjo, Emilio Mola and Manuel Goded Llopis, Franco emerged as the remaining leader of the Nationalist side.

The coup was supported by military units in Morocco, Pamplona, Burgos, Zaragoza, Valladolid, Cádiz, Córdoba, and Seville. However, rebelling units in almost all important cities—such as Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia, Bilbao, and Málaga—did not gain control. Those cities remained under the control of the government, leaving Spain militarily and politically divided. The Nationalists and the Republican government fought for control of the country. The Nationalist forces received munitions, soldiers, and air support from Fascist Italy, Nazi Germany and Portugal, while the Republican side received support from the Soviet Union and Mexico. Other countries, such as the United Kingdom, France, and the United States, continued to recognise the Republican government but followed an official policy of non-intervention. Despite this policy, tens of thousands of citizens from non-interventionist countries directly participated in the conflict. They fought mostly in the pro-Republican International Brigades, which also included several thousand exiles from pro-Nationalist regimes.

The Nationalists advanced from their strongholds in the south and west, capturing most of Spain's northern coastline in 1937. They also besieged Madrid and the area to its south and west for much of the war. After much of Catalonia was captured in 1938 and 1939, and Madrid cut off from Barcelona, the Republican military position became hopeless. Following the fall without resistance of Barcelona in January 1939, the Francoist regime was recognised by France and the United Kingdom in February 1939. On 5 March 1939, in response to an alleged increasing communist dominance of the republican government and the deteriorating military situation, Colonel Segismundo Casado led a military coup against the Republican government, with the intention of seeking peace with the Nationalists. These peace overtures, however, were rejected by Franco. Following internal conflict between Republican factions in Madrid in the same month, Franco entered the capital and declared victory on 1 April 1939. Hundreds of thousands of Spaniards fled to refugee camps in southern France.[16] Those associated with the losing Republicans who stayed were persecuted by the victorious Nationalists. Franco established a dictatorship in which all right-wing parties were fused into the structure of the Franco regime.[15]

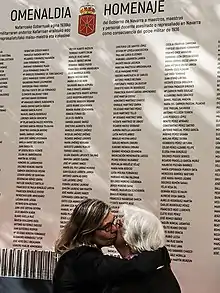

The war became notable for the passion and political division it inspired worldwide and for the many atrocities that occurred. Organised purges occurred in territory captured by Franco's forces so they could consolidate their future regime.[17] Mass executions on a lesser scale also took place in areas controlled by the Republicans,[18] with the participation of local authorities varying from location to location.[19][20]

Background

Absolutism and liberalism

The 19th century was a turbulent time for Spain. Those in favour of reforming the Spanish government vied for political power with conservatives who intended to prevent such reforms from being implemented. In a tradition that started with the Spanish Constitution of 1812, many liberals sought to curtail the authority of the Spanish monarchy as well as to establish a nation-state under their ideology and philosophy. The reforms of 1812 were short-lived as they were almost immediately overturned by King Ferdinand VII when he dissolved the aforementioned constitution. This ended the Trienio Liberal government.[21] Twelve successful coups were carried out between 1814 and 1874.[21] There were several attempts to realign the political system to match social reality. Until the 1850s, the economy of Spain was primarily based on agriculture. There was little development of a bourgeois industrial or commercial class. The land-based oligarchy remained powerful; a small number of people held large estates called latifundia as well as all of the important positions in government.[22] In addition to these regime changes and hierarchies, there was a series of civil wars that transpired in Spain known as the Carlist Wars throughout the middle of the century. There were three such wars: the First Carlist War (1833–1840), the Second Carlist War (1846–1849), and the Third Carlist War (1872–1876). During these wars, a right-wing political movement known as Carlism fought to institute a monarchial dynasty under a different branch of the House of Bourbon descended from Don Infante Carlos María Isidro of Molina.

Glorious Revolution and First Republic

In 1868, popular uprisings led to the overthrow of Queen Isabella II of the House of Bourbon. Two distinct factors led to the uprisings: a series of urban riots and a liberal movement within the middle classes and the military (led by General Joan Prim), which was concerned about the ultra-conservatism of the monarchy. In 1873, Isabella's replacement, King Amadeo I of the House of Savoy, abdicated due to increasing political pressure, and the short-lived First Spanish Republic was proclaimed.[23][24] The Republic was marred with political instability and conflicts and was quickly overthrown by a coup d'état by General Arsenio Martínez Campos in December 1874, after which the Bourbons were restored to the throne in the figure of Alfonso XII, Isabella's son.[25]

Restoration

After the restoration, Carlists and anarchists emerged in opposition to the monarchy.[26][27] Alejandro Lerroux, Spanish politician and leader of the Radical Republican Party, helped to bring republicanism to the fore in Catalonia—a region of Spain with its own cultural and societal identity in which poverty was particularly acute at the time.[28] Conscription was a controversial policy that was eventually implemented by the government of Spain. As evidenced by the Tragic Week in 1909, resentment and resistance were factors that continued well into the 20th century.[29]

Spain was neutral in World War I. Following the war, wide swathes of Spanish society, including the armed forces, united in hopes of removing the corrupt central government of the country in Madrid, but these circles were ultimately unsuccessful.[30] Popular perception of communism as a major threat significantly increased during this period.[31]

Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera

In 1923, a military coup brought Miguel Primo de Rivera to power. As a result, Spain transitioned to government by military dictatorship.[32] Support for the Rivera regime gradually faded, and he resigned in January 1930. He was replaced by General Dámaso Berenguer, who was in turn himself replaced by Admiral Juan Bautista Aznar-Cabañas; both men continued a policy of rule by decree. There was little support for the monarchy in the major cities. Consequently, much like Amadeo I nearly sixty years earlier, King Alfonso XIII of Spain relented to popular pressure for the establishment of a republic in 1931 and called municipal elections for 12 April of that year. Left-wing entities such as the socialist and liberal republicans won almost all the provincial capitals and, following the resignation of Aznar's government, Alfonso XIII fled the country.[33] At this time, the Second Spanish Republic was formed. This republic remained in power until the culmination of the civil war five years later.[34]

Second Republic

The revolutionary committee headed by Niceto Alcalá-Zamora became the provisional government, with Alcalá-Zamora himself as president and head of state.[35] The republic had broad support from all segments of society.[36] In May, an incident where a taxi driver was attacked outside a monarchist club sparked anti-clerical violence throughout Madrid and south-west portion of the country. The slow response on the part of the government disillusioned the right and reinforced their view that the Republic was determined to persecute the church. In June and July, the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) called several strikes, which led to a violent incident between CNT members and the Civil Guard and a brutal crackdown by the Civil Guard and the army against the CNT in Seville. This led many workers to believe the Spanish Second Republic was just as oppressive as the monarchy, and the CNT announced its intention of overthrowing it via revolution.[37]

Constituent Cortes and left-wing government (1931-1933)

Elections in June 1931 returned a large majority of Republicans and Socialists.[25] With the onset of the Great Depression, the government tried to assist rural Spain by instituting an eight-hour day and redistributing land tenure to farm workers.[38][39] The rural workers lived in some of the worst poverty in Europe at the time and the government tried to increase their wages and improve working conditions. This estranged small and medium landholders who used hired labour. The Law of Municipal Boundaries forbade the hiring of workers from outside the locality of the owner's holdings. Since not all localities had enough labour for the tasks required, the law had unintended negative consequences, such as sometimes shutting out peasants and renters from the labour market when they needed extra income as pickers. Labour arbitration boards were set up to regulate salaries, contracts and working hours; they were more favourable to workers than employers and thus the latter became hostile to them. A decree in July 1931 increased overtime pay and several laws in late 1931 restricted whom landowners could hire. Other efforts included decrees limiting the use of machinery, efforts to create a monopoly on hiring, strikes and efforts by unions to limit women's employment to preserve a labour monopoly for their members. Class struggle intensified as landowners turned to counterrevolutionary organisations and local oligarchs. Strikes, workplace theft, arson, robbery and assaults on shops, strikebreakers, employers and machines became increasingly common. Ultimately, the reforms of the Republican-Socialist government alienated as many people as they pleased.[40]

_before_it_was_burned_by_Republicans.jpg.webp)

_after_it_was_burned_by_Republicans.jpg.webp)

Republican Manuel Azaña became prime minister of a minority government in October 1931.[43][44] Fascism remained a reactive threat and it was facilitated by controversial reforms to the military.[45] In December, a new reformist, liberal, and democratic constitution was declared. It included strong provisions enforcing a broad secularisation of the Catholic country, which included the abolition of Catholic schools and charities, a move which was met with opposition.[46] At this point, once the constituent assembly had fulfilled its mandate of approving a new constitution, it probably should have arranged for regular parliamentary elections and adjourned. However, fearing the increasing popular opposition, the Radical and Socialist majority postponed the regular elections, prolonging their time in power for two more years. Diaz's republican government initiated numerous reforms to, in their view, modernize the country. In 1932, the Jesuits, who were in charge of the best schools throughout the country, were banned, and their property was confiscated. The army was reduced. Landowners were expropriated. Home rule was granted to Catalonia, with a local parliament and a president of its own.[47] In June 1933, Pope Pius XI issued the encyclical Dilectissima Nobis, "On Oppression of the Church of Spain", raising his voice against the persecution of the Catholic Church in Spain.[48]

Right-wing government (1933-1936)

In November 1933, the right-wing parties won the general election.[49] The causal factors were increased resentment of the incumbent government caused by a controversial decree implementing land reform[50] and by the Casas Viejas incident,[51] and the formation of a right-wing alliance, Spanish Confederation of Autonomous Right-wing Groups (CEDA). Another factor was the recent enfranchisement of women, most of whom voted for centre-right parties.[52] According to Stanley G. Payne and Jesús Palacios Tapias, left Republicans attempted to have Niceto Alcalá Zamora cancel the electoral results but did not succeed. Despite CEDA's electoral victory, president Alcalá-Zamora declined to invite its leader, Gil Robles, to form a government fearing CEDA's monarchist sympathies and proposed changes to the constitution. Instead, he invited the Radical Republican Party's Alejandro Lerroux to do so. Despite receiving the most votes, CEDA was denied cabinet positions for nearly a year.[53][54]

Events in the period after November 1933, called the "black biennium", seemed to make a civil war more likely.[55] Alejandro Lerroux of the Radical Republican Party (RRP) formed a government, reversing changes made by the previous administration[56] and granting amnesty to the collaborators of the unsuccessful uprising by General José Sanjurjo in August 1932.[57][58] Some monarchists joined with the then fascist-nationalist Falange Española y de las JONS ("Falange") to help achieve their aims.[59] Open violence occurred in the streets of Spanish cities, and militancy continued to increase,[60] reflecting a movement towards radical upheaval, rather than peaceful democratic means as solutions.[61] A small insurrection by anarchists occurred in December 1933 in response to CEDA's victory, in which around 100 people died.[62] After a year of intense pressure, CEDA, the party with the most seats in parliament, finally succeeded in forcing the acceptance of three ministries. The Socialists (PSOE) and Communists reacted with an insurrection for which they had been preparing for nine months.[63] The rebellion developed into a bloody revolutionary uprising, against the existing order. Fairly well armed revolutionaries managed to take the whole province of Asturias, murdered numerous policemen, clergymen, and civilians, and destroyed religious buildings including churches, convents, and part of the university at Oviedo.[64] Rebels in the occupied areas proclaimed revolution for the workers and abolished existing currency.[65] The rebellion was crushed in two weeks by the Spanish Navy and the Spanish Republican Army, the latter using mainly Moorish colonial troops from Spanish Morocco.[66] Azaña was in Barcelona that day, and the Lerroux-CEDA government tried to implicate him. He was arrested and charged with complicity. In fact, Azaña had no connection with the rebellion and was released from prison in January 1935.[67]

In sparking an uprising, the non-anarchist socialists, like the anarchists, manifested their conviction that the existing political order was illegitimate.[68] The Spanish historian Salvador de Madariaga, an Azaña supporter and an exiled vocal opponent of Francisco Franco, wrote a sharp criticism of the left's participation in the revolt: "The uprising of 1934 is unforgivable. The argument that Mr Gil Robles tried to destroy the Constitution to establish fascism was, at once, hypocritical and false. With the rebellion of 1934, the Spanish left lost even the shadow of moral authority to condemn the rebellion of 1936."[69]

Reversals of land reform resulted in expulsions, firings, and arbitrary changes to working conditions in the central and southern countryside in 1935, with landowners' behaviour at times reaching "genuine cruelty", with violence against farmworkers and socialists, which caused several deaths. One historian argued that the behaviour of the right in the southern countryside was one of the main causes of hatred during the Civil War and possibly even the Civil War itself.[70] Landowners taunted workers by saying that if they went hungry, they should "Go eat the Republic!"[71][72] Bosses fired leftist workers and imprisoned trade union and socialist militants, and wages were reduced to "salaries of hunger".[73]

In 1935, the government led by the Radical Republican Party went through a series of crises. After a number of corruption scandals, President Niceto Alcalá-Zamora, who was hostile to this government, called another election.

Popular Front's victory and escalation

The Popular Front narrowly won the 1936 general election. The revolutionary left-wing masses took to the streets and freed prisoners. In the thirty-six hours following the election, sixteen people were killed (mostly by police officers attempting to maintain order or to intervene in violent clashes) and thirty-nine were seriously injured. Also, fifty churches and seventy conservative political centres were attacked or set ablaze.[74] Manuel Azaña was called to form a government before the electoral process had ended. He shortly replaced Zamora as president, taking advantage of a constitutional loophole. Convinced that the left was no longer willing to follow the rule of law and that its vision of Spain was under threat, the right abandoned the parliamentary option and began planning to overthrow the republic, rather than to control it.[75]

PSOE's left wing socialists started to take action. Julio Álvarez del Vayo talked about "Spain' being converted into a socialist Republic in association with the Soviet Union". Francisco Largo Caballero declared that "the organized proletariat will carry everything before it and destroy everything until we reach our goal".[76] The country had rapidly become anarchic. Even the staunch socialist Indalecio Prieto, at a party rally in Cuenca in May 1936, complained: "we have never seen so tragic a panorama or so great a collapse as in Spain at this moment. Abroad, Spain is classified as insolvent. This is not the road to socialism or communism but to desperate anarchism without even the advantage of liberty".[76] The disenchantment with Azaña's ruling was also voiced by Miguel de Unamuno, a republican and one of Spain's most respected intellectuals who, in June 1936, told a reporter who published his statement in El Adelanto that President Manuel Azaña should commit suicide "as a patriotic act".[77]

Laia Balcells observes that polarisation in Spain just before the coup was so intense that physical confrontations between leftists and rightists were a routine occurrence in most localities; six days before the coup occurred, there was a riot between the two in the province of Teruel. Balcells notes that Spanish society was so divided along Left-Right lines that the monk Hilari Raguer stated that in his parish, instead of playing "cops and robbers", children would sometimes play "leftists and rightists".[78] Within the first month of the Popular Front's government, nearly a quarter of the provincial governors had been removed due to their failure to prevent or control strikes, illegal land occupation, political violence and arson. The Popular Front government was more likely to prosecute rightists for violence than leftists who committed similar acts. Azaña was hesitant to use the army to shoot or stop rioters or protestors as many of them supported his coalition. On the other hand, he was reluctant to disarm the military as he believed he needed them to stop insurrections from the extreme left. Illegal land occupation became widespread—poor tenant farmers knew the government was disinclined to stop them. By April 1936, nearly 100,000 peasants had appropriated 400,000 hectares of land and perhaps as many as 1 million hectares by the start of the civil war; for comparison, the 1931–33 land reform had granted only 6,000 peasants 45,000 hectares. As many strikes occurred between April and July as had occurred in the entirety of 1931. Workers increasingly demanded less work and more pay. "Social crimes"—refusing to pay for goods and rent—became increasingly common by workers, particularly in Madrid. In some cases, this was done in the company of armed militants. Conservatives, the middle classes, businessmen and landowners became convinced that revolution had already begun.[79]

Prime Minister Santiago Casares Quiroga ignored warnings of a military conspiracy involving several generals, who decided that the government had to be replaced to prevent the dissolution of Spain.[80] Both sides had become convinced that, if the other side gained power, it would discriminate against their members and attempt to suppress their political organisations.[81]

Military coup

Background

Shortly after the Popular Front's victory in the 1936 election, various groups of officers, both active and retired, got together to begin discussing the prospect of a coup. It would only be by the end of April that General Emilio Mola would emerge as the leader of a national conspiracy network.[82] The Republican government acted to remove suspect generals from influential posts. Franco was sacked as chief of staff and transferred to command of the Canary Islands.[83] Manuel Goded Llopis was removed as inspector general and was made general of the Balearic Islands. Emilio Mola was moved from head of the Army of Africa to military commander of Pamplona in Navarre.[84] This, however, allowed Mola to direct the mainland uprising. General José Sanjurjo became the figurehead of the operation and helped reach an agreement with the Carlists.[84] Mola was chief planner and second in command.[75] José Antonio Primo de Rivera was put in prison in mid-March in order to restrict the Falange.[84] However, government actions were not as thorough as they might have been, and warnings by the Director of Security and other figures were not acted upon.[83]

The revolt was devoid of any particular ideology. The major goal was to put an end to anarchical disorder.[85] Mola's plan for the new regime was envisioned as a "republican dictatorship", modelled after Salazar's Portugal and as a semi-pluralist authoritarian regime rather than a totalitarian fascist dictatorship. The initial government would be an all-military "Directory", which would create a "strong and disciplined state". General Sanjurjo would be the head of this new regime, due to being widely liked and respected within the military, though his position would be largely symbolic due to his lack of political talent. The 1931 Constitution would be suspended, replaced by a new "constituent parliament" which would be chosen by a new politically purged electorate, who would vote on the issue of republic versus monarchy. Certain liberal elements would remain, such as separation of church and state as well as freedom of religion. Agrarian issues would be solved by regional commissioners on the basis of smallholdings, but collective cultivation would be permitted in some circumstances. Legislation prior to February 1936 would be respected. Violence would be required to destroy opposition to the coup, though it seems Mola did not envision the mass atrocities and repression that would ultimately manifest during the civil war.[86][87] Of particular importance to Mola was ensuring the revolt was at its core an Army affair, one that would not be subject to special interests and that the coup would make the armed forces the basis for the new state.[88] However, the separation of church and state was forgotten once the conflict assumed the dimension of a war of religion, and military authorities increasingly deferred to the Church and to the expression of Catholic sentiment.[89] However, Mola's program was vague and only a rough sketch, and there were disagreements among coupists about their vision for Spain.[90][91]

On 12 June, Prime Minister Casares Quiroga met General Juan Yagüe, who falsely convinced Casares of his loyalty to the republic.[92] Mola began serious planning in the spring. Franco was a key player because of his prestige as a former director of the military academy and as the man who suppressed the Asturian miners' strike of 1934.[75] He was respected in the Army of Africa, the Army's toughest troops.[93] He wrote a cryptic letter to Casares on 23 June, suggesting that the military was disloyal, but could be restrained if he were put in charge. Casares did nothing, failing to arrest or buy off Franco.[93] With the help of the British intelligence agents Cecil Bebb and Hugh Pollard, the rebels chartered a Dragon Rapide aircraft (paid for with help from Juan March, the wealthiest man in Spain at the time)[94] to transport Franco from the Canary Islands to Spanish Morocco.[95] The plane flew to the Canaries on 11 July, and Franco arrived in Morocco on 19 July.[96] According to Stanley Payne, Franco was offered this position as Mola's planning for the coup had become increasingly complex and it did not look like it would be as swift as he hoped, instead likely turning into a miniature civil war that would last several weeks. Mola thus had concluded that the troops in Spain were insufficient for the task and that it would be necessary to use elite units from North Africa, something which Franco had always believed would be necessary.[97]

On 12 July 1936, Falangists in Madrid killed police officer Lieutenant José Castillo of the Guardia de Asalto (Assault Guard). Castillo was a Socialist party member who, among other activities, was giving military training to the UGT youth. Castillo had led the Assault Guards that violently suppressed the riots after the funeral of Guardia Civil lieutenant Anastasio de los Reyes. (Los Reyes had been shot by anarchists during 14 April military parade commemorating the five years of the Republic.)[96]

Assault Guard Captain Fernando Condés was a close personal friend of Castillo. The next day, after getting the approval of the minister of interior to illegally arrest specified members of parliament, he led his squad to arrest José María Gil-Robles y Quiñones, founder of CEDA, as a reprisal for Castillo's murder. But he was not at home, so they went to the house of José Calvo Sotelo, a leading Spanish monarchist and a prominent parliamentary conservative.[98] Luis Cuenca, a member of the arresting group and a Socialist who was known as the bodyguard of PSOE leader Indalecio Prieto, summarily executed Calvo Sotelo by shooting him in the back of the neck.[98] Hugh Thomas concludes that Condés intended to arrest Sotelo, and that Cuenca acted on his own initiative, although he acknowledges other sources dispute this finding.[99]

Massive reprisals followed.[98] The killing of Calvo Sotelo with police involvement aroused suspicions and strong reactions among the government's opponents on the right.[99] Although the nationalist generals were already planning an uprising, the event was a catalyst and a public justification for a coup.[98] Stanley Payne claims that before these events, the idea of rebellion by army officers against the government had weakened; Mola had estimated that only 12% of officers reliably supported the coup and at one point considered fleeing the country for fear he was already compromised and had to be convinced to remain by his co-conspirators.[100] However, the kidnapping and murder of Sotelo transformed the "limping conspiracy" into a revolt that could trigger a civil war.[101][102] The arbitrary use of lethal force by the state and a lack of action against the attackers led to public disapproval of the government. No effective punitive, judicial or even investigative action was taken; Payne points to a possible veto by socialists within the government who shielded the killers who had been drawn from their ranks. The murder of a parliamentary leader by state police was unprecedented, and the belief that the state had ceased to be neutral and effective in its duties encouraged important sectors of the right to join the rebellion.[103] Within hours of learning of the murder and the reaction, Franco changed his mind on rebellion and dispatched a message to Mola to display his firm commitment.[104]

The Socialists and Communists, led by Indalecio Prieto, demanded that arms be distributed to the people before the military took over. The prime minister was hesitant.[98]

Beginning of the coup

.svg.png.webp)

|

Initial Nationalist zone – July 1936 Nationalist advance until September 1936 Nationalist advance until October 1937 Nationalist advance until November 1938 Nationalist advance until February 1939 Last area under Republican control |

|

The uprising's timing was fixed at 17 July, at 17:01, agreed to by the leader of the Carlists, Manuel Fal Conde.[105] However, the timing was changed—the men in the Morocco protectorate were to rise up at 05:00 on 18 July and those in Spain proper a day later so that control of Spanish Morocco could be achieved and forces sent back to the Iberian Peninsula to coincide with the risings there.[106] The rising was intended to be a swift coup d'état, but the government retained control of most of the country.[107]

Control over Spanish Morocco was all but certain.[108] The plan was discovered in Morocco on 17 July, which prompted the conspirators to enact it immediately. Little resistance was encountered. The rebels shot 189 people.[109] Goded and Franco immediately took control of the islands to which they were assigned.[75] On 18 July, Casares Quiroga refused an offer of help from the CNT and Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT), leading the groups to proclaim a general strike—in effect, mobilising. They opened weapons caches, some buried since the 1934 risings, and formed militias.[110] The paramilitary security forces often waited for the outcome of militia action before either joining or suppressing the rebellion. Quick action by either the rebels or anarchist militias was often enough to decide the fate of a town.[111] General Gonzalo Queipo de Llano secured Seville for the rebels, arresting a number of other officers.[112]

Outcome

The rebels failed to take any major cities with the critical exception of Seville, which provided a landing point for Franco's African troops, and the primarily conservative and Catholic areas of Old Castile and León, which fell quickly.[107] They took Cádiz with help from the first troops from Africa.[113]

The government retained control of Málaga, Jaén, and Almería. In Madrid, the rebels were hemmed into the Cuartel de la Montaña siege, which fell with considerable bloodshed. Republican leader Casares Quiroga was replaced by José Giral, who ordered the distribution of weapons among the civilian population.[114] This facilitated the defeat of the army insurrection in the main industrial centres, including Madrid, Barcelona, and Valencia, but it allowed anarchists to take control of Barcelona along with large swathes of Aragón and Catalonia.[115] General Goded surrendered in Barcelona and was later condemned to death.[116] The Republican government ended up controlling almost all the east coast and central area around Madrid, as well as most of Asturias, Cantabria and part of the Basque Country in the north.[117]

Hugh Thomas suggested that the civil war could have ended in the favour of either side almost immediately if certain decisions had been taken during the initial coup. Thomas argues that if the government had taken steps to arm the workers, they could probably have crushed the coup very quickly. Conversely, if the coup had risen everywhere in Spain on the 18th rather than be delayed, it could have triumphed by the 22nd.[118] While the militias that rose to meet the rebels were often untrained and poorly armed (possessing only a small number of pistols, shotguns and dynamite), this was offset by the fact that the rebellion was not universal. In addition, the Falangists and Carlists were themselves often not particularly powerful fighters either. However, enough officers and soldiers had joined the coup to prevent it from being crushed swiftly.[101]

The rebels termed themselves Nacionales, normally translated "Nationalists", although the former implies "true Spaniards" rather than a nationalistic cause.[119] The result of the coup was a nationalist area of control containing 11 million of Spain's population of 25 million.[120] The Nationalists had secured the support of around half of Spain's territorial army, some 60,000 men, joined by the Army of Africa, made up of 35,000 men,[121] and just under half of Spain's militaristic police forces, the Assault Guards, the Civil Guards, and the Carabineers.[122] Republicans controlled under half of the rifles and about a third of both machine guns and artillery pieces.[123]

The Spanish Republican Army had just 18 tanks of a sufficiently modern design, and the Nationalists took control of 10.[124] Naval capacity was uneven, with the Republicans retaining a numerical advantage, but with the Navy's top commanders and two of the most modern ships, heavy cruisers Canarias—captured at the Ferrol shipyard—and Baleares, in Nationalist control.[125] The Spanish Republican Navy suffered from the same problems as the army—many officers had defected or been killed after trying to do so.[124] Two-thirds of air capability was retained by the government—however, the whole of the Republican Air Force was very outdated.[126]

Combatants

The war was cast by Republican sympathisers as a struggle between tyranny and freedom, and by Nationalist supporters as communist and anarchist red hordes versus Christian civilisation.[102] Nationalists also claimed they were bringing security and direction to an ungoverned and lawless country.[102] Spanish politics, especially on the left, was quite fragmented: on the one hand socialists and communists supported the republic but on the other, during the republic, anarchists had mixed opinions, though both major groups opposed the Nationalists during the Civil War; the latter, in contrast, were united by their fervent opposition to the Republican government and presented a more unified front.[127]

The coup divided the armed forces fairly evenly. One historical estimate suggests that there were some 87,000 troops loyal to the government and some 77,000 joining the insurgency,[128] though some historians suggest that the Nationalist figure should be revised upwards and that it probably amounted to some 95,000.[128]

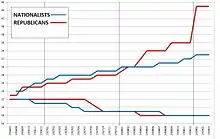

During the first few months, both armies were joined in high numbers by volunteers, Nationalists by some 100,000 men and Republicans by some 120,000.[129] From August, both sides launched their own, similarly scaled conscription schemes, resulting in further massive growth of their armies. Finally, the final months of 1936 saw the arrival of foreign troops, International Brigades joining the Republicans and Italian Corpo Truppe Volontarie (CTV), German Legion Condor and Portuguese Viriatos joining the Nationalists. The result was that in April 1937 there were some 360,000 soldiers in the Republican ranks and some 290,000 in the Nationalist ones.[130]

The armies kept growing. The principal source of manpower was conscription; both sides continued and expanded their schemes, the Nationalists drafting more aggressively, and there was little room left for volunteering. Foreigners contributed little to further growth; on the Nationalist side the Italians scaled down their engagement, while on the Republican side the influx of new interbrigadistas did not cover losses on the front. At the turn of 1937–1938, each army numbered about 700,000.[131]

Throughout 1938, the principal if not exclusive source of new men was a draft; at this stage it was the Republicans who conscripted more aggressively, and only 47% of their combatants were in age corresponding to the Nationalist conscription age limits.[132] Just prior to the Battle of Ebro, Republicans achieved their all-time high, slightly above 800,000; yet Nationalists numbered 880,000.[133] The Battle of Ebro, fall of Catalonia and collapsing discipline caused a great shrinking of Republican troops. In late February 1939, their army was 400,000[134] compared to more than double that number of Nationalists. In the moment of their final victory, Nationalists commanded over 900,000 troops.[135]

The total number of Spaniards serving in the Republican forces was officially stated as 917,000; later scholarly work estimated the number as "well over 1 million men",[136] though other studies claim the Republican total of 1.75 million (including non-Spaniards)[137] and "27 age groups, ranging from 18 to 44 years old".[138] The total number of Spaniards serving in the Nationalist units is estimated between "nearly 1 million men",[136] and 1.26 million (including non-Spaniards),[139] which comprised "15 age groups, ranging from 18 to 32 years old"[140]

Republicans

.svg.png.webp)

Only two countries openly and fully supported the Republic: the Mexican government and the USSR. From them, especially the USSR, the Republic received diplomatic support, volunteers, weapons and vehicles. Other countries remained neutral; this neutrality faced serious opposition from sympathizers in the United States and United Kingdom, and to a lesser extent in other European countries and from Marxists worldwide. This led to formation of the International Brigades, thousands of foreigners of all nationalities who voluntarily went to Spain to aid the Republic in the fight; they meant a great deal to morale but militarily were not very significant.

The Republic's supporters within Spain ranged from centrists who supported a moderately capitalist liberal democracy to revolutionary anarchists who opposed the Republic but sided with it against the coup forces. Their base was primarily secular and urban but also included landless peasants and was particularly strong in industrial regions like Asturias, the Basque country, and Catalonia.[141]

This faction was called variously leales "Loyalists" by supporters, "Republicans", the "Popular Front", or "the government" by all parties; and/or los rojos "the Reds" by their opponents.[142] Republicans were supported by urban workers, agricultural labourers, and parts of the middle class.[143]

The conservative, strongly Catholic Basque country, along with Catholic Galicia and the more left-leaning Catalonia, sought autonomy or independence from the central government of Madrid. The Republican government allowed for the possibility of self-government for the two regions,[144] whose forces were gathered under the People's Republican Army (Ejército Popular Republicano, or EPR), which was reorganised into mixed brigades after October 1936.[145]

A few well-known people fought on the Republican side, such as English novelist George Orwell (who wrote Homage to Catalonia (1938), an account of his experiences in the war)[146] and Canadian thoracic surgeon Norman Bethune, who developed a mobile blood-transfusion service for front-line operations.[147] Simone Weil briefly fought with the anarchist columns of Buenaventura Durruti.[148]

At the beginning of the war, the Republicans outnumbered the Nationalists ten to one on the front in Aragon, but by January 1937, that advantage had dropped to four to one.[149]

Nationalists

The Nacionales or Nationalists, also called "insurgents", "rebels" or, by opponents, Franquistas or "fascists" —feared national fragmentation and opposed the separatist movements. They were chiefly defined by their anti-communism, which galvanised diverse or opposed movements like Falangists and monarchists. Their leaders had a generally wealthier, more conservative, monarchist, landowning background.[150]

The Nationalist side included the Carlists and Alfonsists, Spanish nationalists, the fascist Falange, and most conservatives and monarchist liberals. Virtually all Nationalist groups had strong Catholic convictions and supported the native Spanish clergy.[142] The Nationals included the majority of the Catholic clergy and practitioners (outside of the Basque region), important elements of the army, most large landowners, and many businessmen.[102] The Nationalist base largely consisted of the middle classes, conservative peasant smallholders in the North and Catholics in general. Catholic support became particularly pronounced as a consequence of the burning of churches and killing of priests in most leftists zones during the first six months of the war. By mid-1937, the Catholic Church gave its official blessing to the Franco regime; religious fervor was a major source of emotional support for the Nationalists during the civil war.[151] Michael Seidmann reports that devout Catholics, such as seminary students, often volunteered to fight and would die in disproportionate numbers in the war. Catholic confession cleared the soldiers of moral doubt and increased fighting ability; Republican newspapers described Nationalist priests as ferocious in battle and Indalecio Prieto remarked that the enemy he feared most was "the requeté who has just received communion".[152]

.jpg.webp)

One of the rightists' principal motives was to confront the anti-clericalism of the Republican regime and to defend the Catholic Church,[150] which had been targeted by opponents, including Republicans, who blamed the institution for the country's ills. The Church opposed many of the Republicans' reforms, which were fortified by the Spanish Constitution of 1931.[153] Articles 24 and 26 of the 1931 constitution had banned the Society of Jesus. This proscription deeply offended many within the conservative fold. The revolution in the Republican zone at the outset of the war, in which 7,000 clergy and thousands of lay people were killed, deepened Catholic support for the Nationalists.[154][155]

Prior to the war, during the Asturian miners' strike of 1934, religious buildings were burnt and at least 100 clergy, religious civilians, and pro-Catholic police were killed by revolutionaries.[151][156] Franco had brought in Spain's colonial Army of Africa (Spanish: Ejército de África or Cuerpo de Ejército Marroquí) and reduced the miners to submission by heavy artillery attacks and bombing raids. The Spanish Legion committed atrocities and the army carried out summary executions of leftists. The repression in the aftermath was brutal and prisoners were tortured.[157]

The Moroccan Fuerzas Regulares Indígenas joined the rebellion and played a significant role in the civil war.[158]

While the Nationalists are often assumed to have drawn in the majority of military officers, this is a somewhat simplistic analysis. The Spanish army had its own internal divisions and long-standing rifts. Officers supporting the coup tended to be africanistas (men who fought in North Africa between 1909 and 1923) while those who stayed loyal tended to be peninsulares (men who stayed back in Spain during this period). This was because during Spain's North African campaigns, the traditional promotion by seniority was suspended in favour of promotion by merit through battlefield heroism. This tended to benefit younger officers starting their careers as they could, while older officers had familial commitments that made it harder for them to be deployed in North Africa. Officers in front line combat corps (primarily infantry and cavalry) benefited over those in technical corps (those in artillery, engineering etc.) because they had more chances to demonstrate the requisite battlefield heroism and had also traditionally enjoyed promotion by seniority. The peninsulares resented seeing the africanistas rapidly leapfrog through the ranks, while the africanistas themselves were seen as swaggering and arrogant, further fuelling resentment. Thus, when the coup occurred, officers who joined the rebellion, particularly from Franco's rank downwards, were often africanistas, while senior officers and those in non-front line positions tended to oppose it (though a small number of senior africanistas opposed the coup as well).[101] It has also been argued that officers who stayed loyal to the Republic were more likely to have been promoted and to have been favoured by the Republican regime (such as those in the Aviation and Assault Guard units).[159] Thus, while often thought of as a "rebellion of the generals", this is not correct. Of the eighteen division generals, only four rebelled (of the four division generals without postings, two rebelled and two remained loyal). Fourteen of the fifty-six brigade generals rebelled. The rebels tended to draw from less senior officers. Of the approximately 15,301 officers, just over half rebelled.[160]

Other factions

Catalan and Basque nationalists were divided. Left-wing Catalan nationalists sided with the Republicans, while Conservative Catalan nationalists were far less vocal in supporting the government, due to anti-clericalism and confiscations occurring in areas within its control. Basque nationalists, heralded by the conservative Basque Nationalist Party, were mildly supportive of the Republican government, although some in Navarre sided with the uprising for the same reasons influencing conservative Catalans. Notwithstanding religious matters, Basque nationalists, who were for the most part Catholic, generally sided with the Republicans, although the PNV, Basque nationalist party, was reported passing the plans of Bilbao defences to the Nationalists, in an attempt to reduce the duration and casualties of siege.[161]

Foreign involvement

The Spanish Civil War exposed political divisions across Europe. The right and the Catholics supported the Nationalists to stop the spread of Bolshevism. On the left, including labour unions, students and intellectuals, the war represented a necessary battle to stop the spread of fascism. Anti-war and pacifist sentiment was strong in many countries, leading to warnings that the Civil War could escalate into a second world war.[162] In this respect, the war was an indicator of the growing instability across Europe.[163]

The Spanish Civil War involved large numbers of non-Spanish citizens who participated in combat and advisory positions. Britain and France led a political alliance of 27 nations that pledged non-intervention, including an embargo on all arms exports to Spain. The United States unofficially adopted a position of non-intervention as well, despite abstaining from joining the alliance (due in part to its policy of political isolation). Germany, Italy and the Soviet Union signed on officially, but ignored the embargo. The attempted suppression of imported material was largely ineffective, and France was especially accused of allowing large shipments to Republican troops.[164] The clandestine actions of the various European powers were, at the time, considered to be risking another world war, alarming antiwar elements across the world.[165]

The League of Nations' reaction to the war was influenced by a fear of communism,[166] and was insufficient to contain the massive importation of arms and other war resources by the fighting factions. Although a Non-Intervention Committee was formed, its policies accomplished very little and its directives were ineffective.[167]

Support for the Nationalists

Italy

As the conquest of Ethiopia in the Second Italo-Ethiopian War made the Italian government confident in its military power, Benito Mussolini joined the war to secure Fascist control of the Mediterranean,[168] supporting the Nationalists to a greater extent than Nazi Germany did.[169] The Royal Italian Navy (Italian: Regia Marina) played a substantial role in the Mediterranean blockade, and ultimately Italy supplied machine guns, artillery, aircraft, tankettes, the Aviazione Legionaria, and the Corpo Truppe Volontarie (CTV) to the Nationalist cause.[170] The Italian CTV would, at its peak, supply the Nationalists with 50,000 men.[170] Italian warships took part in breaking the Republican navy's blockade of Nationalist-held Spanish Morocco and took part in naval bombardment of Republican-held Málaga, Valencia, and Barcelona.[171] In addition, the Italian air force made air raids of some note, targeting mainly cities and civilian targets.[172] These Italian commitments were heavily propagandised in Italy proper, and became a point of fascist pride.[172] In total, Italy provided the Nationalists with 660 planes, 150 tanks, 800 artillery pieces, 10,000 machine guns, and 240,747 rifles.[173]

Germany

German involvement began days after fighting broke out in July 1936. Adolf Hitler quickly sent in powerful air and armoured units to assist the Nationalists. The war provided combat experience with the latest technology for the German military. However, the intervention also posed the risk of escalating into a world war for which Hitler was not ready. Therefore, he limited his aid, and instead encouraged Benito Mussolini to send in large Italian units.[174]

Nazi Germany's actions included the formation of the multitasking Condor Legion, a unit composed of volunteers from the Luftwaffe and the German Army (Heer) from July 1936 to March 1939. The Condor Legion proved to be especially useful in the 1936 battle of the Toledo. Germany moved the Army of Africa to mainland Spain in the war's early stages.[175] German operations slowly expanded to include strike targets, most notably—and controversially—the bombing of Guernica which, on 26 April 1937, killed 200 to 300 civilians.[176] Germany also used the war to test new weapons, such as the Luftwaffe Junkers Ju 87 Stukas and Junkers Ju-52 transport Trimotors (used also as Bombers), which showed themselves to be effective.[177]

German involvement was further manifested through undertakings such as Operation Ursula, a U-boat undertaking; and contributions from the Kriegsmarine. The Legion spearheaded many Nationalist victories, particularly in aerial combat,[175] while Spain further provided a proving ground for German tank tactics. The training which German units provided to the Nationalist forces would prove valuable. By the War's end, perhaps 56,000 Nationalist soldiers, encompassing infantry, artillery, aerial and naval forces, had been trained by German detachments.[175]

Hitler's policy for Spain was shrewd and pragmatic. The minutes of a conference at the Reich Chancellery in Berlin on 10 November 1937 summarised his views on foreign policy regarding the Spanish Civil War: "On the other hand, a 100 percent victory for Franco was not desirable either, from the German point of view; rather were we interested in a continuance of the war and in the keeping up of the tension in the Mediterranean."[178][179] Hitler wanted to help Franco just enough to gain his gratitude and to prevent the side supported by the Soviet Union from winning, but not large enough to give the Caudillo a quick victory.[180]

A total of approximately 16,000 German citizens fought in the war, with approximately 300 killed,[181] though no more than 10,000 participated at any one time. German aid to the Nationalists amounted to approximately £43,000,000 ($215,000,000) in 1939 prices,[181][note 3] 15.5% of which was used for salaries and expenses and 21.9% for direct delivery of supplies to Spain, while 62.6% was expended on the Condor Legion.[181] In total, Germany provided the Nationalists with 600 planes and 200 tanks.[182]

Portugal

The Estado Novo regime of Portuguese Prime Minister António de Oliveira Salazar played an important role in supplying Francisco Franco's forces with ammunition and logistical help.[183]

Salazar supported Franco and the Nationalists in their war against the Second Republic forces, as well as the anarchists and the communists. While the Nationalists lacked access to seaports early on, they secured control of the entire border with Portugal by the end of August 1936, thus giving Salazar and his regime a free hand to render whatever assistance to Franco they saw fit without fear of Republican interference or retaliation. Salazar's Portugal helped the Nationalist side receive armaments shipments from abroad, including ordnance when certain Nationalist forces virtually ran out of ammunition. Consequently, the Nationalists called Lisbon "the port of Castile".[184] Later, Franco spoke of Salazar in glowing terms in an interview in the Le Figaro newspaper: "The most complete statesman, the one most worthy of respect, that I have known is Salazar. I regard him as an extraordinary personality for his intelligence, his political sense and his humility. His only defect is probably his modesty."[185]

On 8 September 1936, a naval revolt took place in Lisbon. The crews of two naval Portuguese vessels, the NRP Afonso de Albuquerque and the NRP Dão, mutinied. The sailors, who were affiliated with the Portuguese Communist Party, confined their officers and attempted to sail the ships out of Lisbon to join the Spanish Republican forces fighting in Spain. Salazar ordered the ships to be destroyed by gunfire.[186]

In January 1938, Salazar appointed Pedro Teotónio Pereira as special liaison of the Portuguese government to Franco's government, where he achieved great prestige and influence.[187] In April 1938, Pereira officially became a full-rank Portuguese ambassador to Spain, remaining in this post throughout World War II.[188]

Just a few days before the end of the Spanish Civil War, on 17 March 1939, Portugal and Spain signed the Iberian Pact, a non-aggression treaty that marked the beginning of a new phase in Iberian relations. Meetings between Franco and Salazar played a fundamental role in this new political arrangement.[189] The pact proved to be a decisive instrument in keeping the Iberian Peninsula out of Hitler's continental system.[190]

Despite its discreet direct military involvement—restrained to a somewhat "semi-official" endorsement, by its authoritarian regime—a "Viriatos Legion" volunteer force was organised, but disbanded, due to political unrest.[191] Between 8,000[191] and 12,000[102] would-be legionaries did still volunteer, only now as part of various Nationalist units instead of a unified force. Due to the widespread publicity given to the Viriatos Legion previously, these Portuguese volunteers were still called "Viriatos".[192][193] Portugal was instrumental in providing the Nationalists with organizational skills and reassurance from the Iberian neighbour to Franco and his allies that no interference would hinder the supply traffic directed to the Nationalist cause.[194]

Others

Romanian volunteers were led by Ion Moța, deputy-leader of the Iron Guard ("Legion of the Archangel Michael"), whose group of Seven Legionaries visited Spain in December 1936 to ally their movement with the Nationalists.[195]

Despite the Irish government's prohibition against participating in the war, about 600 Irishmen, followers of the Irish political activist and co-founder of the recently created political party of Fine Gael (unofficially called "The Blue Shirts"), Eoin O'Duffy, known as the "Irish Brigade", went to Spain to fight alongside Franco.[196] The majority of the volunteers were Catholics, and according to O'Duffy had volunteered to help the Nationalists fight against communism.[197][198]

According to Spanish statistics, 1,052 Yugoslavs were recorded as volunteers of which 48% were Croats, 23% Slovenes, 18% Serbs, 2.3% Montenegrins and 1.5% Macedonians.[199]

From 150 to 170 White Russians fought for Franco, of whom 19 perished and many more were wounded.[200] Their attempts at creating a separate unit were turned down by the Francoist government.

Support for the Republicans

International Brigades

On 26 July, just eight days after the revolt had started, an international communist conference was held at Prague to arrange plans to help the Republican Government. It decided to raise an international brigade of 5,000 men and a fund of 1 billion francs.[201] At the same time communist parties throughout the world quickly launched a full-scale propaganda campaign in support of the Popular Front. The Communist International immediately reinforced its activity sending to Spain its leader Georgi Dimitrov, and Palmiro Togliatti the chief of the Communist Party of Italy.[202][203] From August onward aid started to be sent from Russia, over one ship per day arrived at Spain's Mediterranean ports carrying munitions, rifles, machine guns, hand grenades, artillery and trucks. With the cargo came Soviet agents, technicians, instructors and propagandists.[202]

The Communist International immediately started to organize the International Brigades with great care to conceal or minimize the communist character of the enterprise and to make it appear as a campaign on behalf of progressive democracy.[202] Attractive names were deliberately chosen, such as Garibaldi Battalion in Italy, the Canadian "Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion" or Abraham Lincoln Battalion in the United States.[202]

Many non-Spaniards, often affiliated with radical communist or socialist entities, joined the International Brigades, believing that the Spanish Republic was a front line in the war against fascism. The units represented the largest foreign contingent of those fighting for the Republicans. Roughly 40,000 foreign nationals fought with the Brigades, though no more than 18,000 were in the conflict at any given time. They claimed to represent 53 nations.[204]

Significant numbers of volunteers came from France (10,000), Nazi Germany and Austria (5,000), and Italy (3,350). More than 1,000 each came from the Soviet Union, the United States, the United Kingdom, Poland, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Canada.[204] The Thälmann Battalion, a group of Germans, and the Garibaldi Battalion, a group of Italians, distinguished their units during the siege of Madrid. Americans fought in units such as the XV International Brigade ("Abraham Lincoln Brigade"), while Canadians joined the Mackenzie–Papineau Battalion.[205]

More than 500 Romanians fought on the Republican side, including Romanian Communist Party members Petre Borilă and Valter Roman.[206] About 145 men[207] from Ireland formed the Connolly Column, which was immortalized by Irish folk musician Christy Moore in the song "Viva la Quinta Brigada". Some Chinese joined the Brigades;[208] the majority of them eventually returned to China, but some went to prison or to French refugee camps, and a handful remained in Spain.[209]

Soviet Union

Although General Secretary Joseph Stalin had signed the Non-Intervention Agreement, the Soviet Union contravened the League of Nations embargo by providing material assistance to the Republican forces, becoming their only source of major weapons. Unlike Hitler and Mussolini, Stalin tried to do this covertly.[210] Estimates of material provided by the USSR to the Republicans vary between 634 and 806 aircraft, 331 and 362 tanks and 1,034 to 1,895 artillery pieces.[211] Stalin also created Section X of the Soviet Union military to head the weapons shipment operation, called Operation X. Despite Stalin's interest in aiding the Republicans, the quality of arms was inconsistent.[212][213] Many rifles and field guns provided were old, obsolete or otherwise of limited use (some dated back to the 1860s) but the T-26 and BT-5 tanks were modern and effective in combat.[212] The Soviet Union supplied aircraft that were in current service with their own forces but the aircraft provided by Germany to the Nationalists proved superior by the end of the war.[214]

The movement of arms from Russia to Spain was extremely slow. Many shipments were lost or arrived only partially matching what had been authorised.[215] Stalin ordered shipbuilders to include false decks in the design of ships and while at sea, Soviet captains used deceptive flags and paint schemes to evade detection by the Nationalists.[216]

The USSR sent 2,000–3,000 military advisers to Spain; while the Soviet commitment of troops was fewer than 500 men at a time, Soviet volunteers often operated Soviet-made tanks and aircraft, particularly at the beginning of the war.[217][218][219][204] The Spanish commander of every military unit on the Republican side was attended by a "Comissar Politico" of equal rank, who represented Moscow.[220]

The Republic paid for Soviet arms with official Bank of Spain gold reserves, 176 tonnes of which was transferred through France and 510 directly to Russia,[221] which was called Moscow gold.

Also, the Soviet Union directed Communist parties around the world to organise and recruit the International Brigades.[222]

Another significant Soviet involvement was the activity of the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD) inside the Republican rearguard. Communist figures including Vittorio Vidali ("Comandante Contreras"), Iosif Grigulevich, Mikhail Koltsov and, most prominently, Aleksandr Mikhailovich Orlov led operations that included the murders of Catalan anti-Stalinist Communist politician Andrés Nin, the socialist journalist Mark Rein, and the independent left-wing activist José Robles.[223]

Other NKVD-led operations were the murder of the Austrian member of the International Left Opposition and Trotskyist Kurt Landau,[224] and the shooting down (in December 1936) of the French aircraft in which the delegate of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Georges Henny, carried extensive documentation on the Paracuellos massacres to France.[225]

In his book, Partners in Crime: Faustian Bargain, historian Ian Ona Johnson explains that in the 1920s and 30s (during the Spanish Civil War) Germany and Soviet Russia had entered into a partnership centering on economic and military cooperation. This led to the establishment of German military bases and facilities in Russia. This military exchange of war material continued until June 1941, when Germany invaded Stalin's Russia.[226]

Poland

Polish arms sales to Republican Spain took place between September 1936 and February 1939. Politically Poland did not support any of the Spanish Civil War sides, though over time the Warsaw government increasingly tended to favour the Nationalists; sales to the Republicans were motivated exclusively by economic interest. Since Poland was bound by non-intervention obligations, Polish governmental officials and the military disguised sales as commercial transactions mediated by international brokers and targeting customers in various countries, principally in Latin America; there are 54 shipments from Danzig and Gdynia identified. Most hardware were obsolete and worn-out second-rate weapons, though there were also some modern arms delivered; all were 20–30% overpriced. Polish sales amounted to $40m and constituted some 5–7% of overall Republican military spendings, though in terms of quantity certain categories of weaponry, like machine-guns, might have accounted for 50% of all arms delivered. After the USSR Poland was the second largest arms supplier for the Republic. After the USSR, Italy and Germany, Poland was the 4th largest arms supplier to the war-engulfed Spain.[227]

Greece

Greece was officially neutral during the war. It maintained formal diplomatic relations with the Republic, though the Metaxas dictatorship sympathized with the Nationalists. The country joined the non-intervention policy in August 1936, yet from the onset the Athens government connived at arms sales to both sides. The official vendor was Pyrkal or Greek Powder and Cartridge Company (GPCC), and the key personality behind the deal was the GPCC head, Prodromos Bodosakis-Athanasiadis, an entrepreneurial genius. The company partially took advantage of the earlier Schacht Plan, a German-Greek credit agreement which enabled Greek purchases from Rheinmetall-Borsig; some of German products were later re-exported to Republican Spain. However, GPCC was selling its own arms, as the company operated a number of factories, and partially thanks to Spanish sales it became the largest company in Greece.[228]

Most of Greek sales went to the Republic; on part of the Spaniards the deals were negotiated by Grigori Rosenberg, son of well-known Soviet diplomat, and Máximo José Kahn Mussabaun, the Spanish representative in the Thessaloniki consulate. Shipments set off usually from Piraeus, were camouflaged at a deserted island, and with changed flags they proceeded officially to ports in Mexico. It is known that sales continued from August 1936 at least until November 1938. Exact number of shipments is unknown, but it remained significant: by November 1937 34 Greek ships were declared non-compliant with the non-intervention agreement, and the Nationalist navy seized 21 vessels in 1938 alone. Details of sales to the Nationalists are unclear, but it is known they were by far smaller.[228]

Total worth of Greek sales is unknown. One author claims that in 1937 alone, GPCC shipments amounted to $10.9m for the Republicans and $2.7m for the Nationalists, and that in late 1937 Bodosakis signed another contract with the Republicans for £2.1m (around $10m), though it is not clear whether the ammunition contracted was delivered. The arms sold included artillery (e.g., 30 pieces of 155mm guns), machine guns (at least 400), cartridges (at least 11m), bombs (at least 1,500) and explosives (at least 38 tons of TNT).[228] AEKKEA-RAAB, a Greek aviation company, also sold at least 60 aircraft to the Republican Air Force, consisting of R-29 fighters and R-33 trainers.[229]

Mexico

Unlike the United States and major Latin American governments, such as the ABC nations and Peru, the Mexican government supported the Republicans.[230][231] Mexico abstained from following the French-British non-intervention proposals,[230] and provided $2,000,000 in aid and material assistance, which included 20,000 rifles and 20 million cartridges.[230]

Mexico's most important contributions to the Spanish Republic was its diplomatic help, as well as the sanctuary the nation arranged for Republican refugees, including Spanish intellectuals and orphaned children from Republican families. Some 50,000 took refuge, primarily in Mexico City and Morelia, accompanied by $300 million in various treasures still owned by the Left.[232]

France

Fearing it might spark a civil war inside France, the leftist "Popular Front" government in France did not send direct support to the Republicans. French Prime Minister Léon Blum was sympathetic to the republic,[233] fearing that the success of Nationalist forces in Spain would result in the creation of an ally state of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, an alliance that would nearly encircle France.[233] Right-wing politicians opposed any aid and attacked the Blum government.[234] In July 1936, British officials convinced Blum not to send arms to the Republicans and, on 27 July, the French government declared that it would not send military aid, technology or forces to assist the Republican forces.[235] However, Blum made clear that France reserved the right to provide aid should it wish to the Republic: "We could have delivered arms to the Spanish Government [Republicans], a legitimate government... We have not done so, in order not to give an excuse to those who would be tempted to send arms to the rebels [Nationalists]."[236]

On 1 August 1936, a pro-Republican rally of 20,000 people confronted Blum, demanding that he send aircraft to the Republicans, at the same time as right-wing politicians attacked Blum for supporting the Republic and being responsible for provoking Italian intervention on the side of Franco.[236] Germany informed the French ambassador in Berlin that Germany would hold France responsible if it supported "the manoeuvres of Moscow" by supporting the Republicans.[237] On 21 August 1936, France signed the Non-Intervention Agreement.[237] However, the Blum government provided aircraft to the Republicans covertly with Potez 540 bomber aircraft (nicknamed the "Flying Coffin" by Spanish Republican pilots),[238] Dewoitine aircraft, and Loire 46 fighter aircraft being sent from 7 August 1936 to December of that year to Republican forces.[239] France, through the favour of pro-communist air minister Pierre Cot also sent a group of trained fighter pilots and engineers to help the Republicans.[201][240] Also, until 8 September 1936, aircraft could freely pass from France into Spain if they were bought in other countries.[241]

Even after covert support by France to the Republicans ended in December 1936, the possibility of French intervention against the Nationalists remained a serious possibility throughout the war. German intelligence reported to Franco and the Nationalists that the French military was engaging in open discussions about intervention in the war through French military intervention in Catalonia and the Balearic Islands.[242] In 1938, Franco feared an immediate French intervention against a potential Nationalist victory in Spain through French occupation of Catalonia, the Balearic Islands, and Spanish Morocco.[243]

Course of the war

1936

A large air and sealift of Nationalist troops in Spanish Morocco was organised to the southwest of Spain.[244] Coup leader Sanjurjo was killed in a plane crash on 20 July,[245][246] leaving an effective command split between Mola in the North and Franco in the South.[75] This period also saw the worst actions of the so-called "Red" and "White Terrors" in Spain.[247] On 21 July, the fifth day of the rebellion, the Nationalists captured the central Spanish naval base, located in Ferrol, Galicia.[248]

A rebel force under Colonel Alfonso Beorlegui Canet, sent by General Mola and Colonel Esteban García, undertook the Campaign of Gipuzkoa from July to September. The capture of Gipuzkoa isolated the Republican provinces in the north. On 5 September, the Nationalists closed the French border to the Republicans in the battle of Irún.[249] On 15 September San Sebastián, home to a divided Republican force of anarchists and Basque nationalists, was taken by Nationalist soldiers.[194]

The Republic proved ineffective militarily, relying on disorganised revolutionary militias. The Republican government under Giral resigned on 4 September, unable to cope with the situation, and was replaced by a mostly Socialist organisation under Francisco Largo Caballero.[250] The new leadership began to unify central command in the republican zone.[251] The civilian militias were often simply just civilians armed with whatever was available. Thus, they fared poorly in combat, particularly against the professional Army of Africa armed with modern weapons, ultimately contributing to Franco's rapid advance.[252]

.jpg.webp)

On the Nationalist side, Franco was chosen as chief military commander at a meeting of ranking generals at Salamanca on 21 September, now called by the title Generalísimo.[75][255] Franco won another victory on 27 September when his troops relieved the siege of the Alcázar in Toledo,[255] which had been held by a Nationalist garrison under Colonel José Moscardó Ituarte since the beginning of the rebellion, resisting thousands of Republican troops, who completely surrounded the isolated building. Moroccans and elements of the Spanish Legion came to the rescue.[256] Two days after relieving the siege, Franco proclaimed himself Caudillo ("chieftain", the Spanish equivalent of the Italian Duce and the German Führer—meaning: 'director') while forcibly unifying the various and diverse Falangist, Royalist and other elements within the Nationalist cause.[250] The diversion to Toledo gave Madrid time to prepare a defense but was hailed as a major propaganda victory and personal success for Franco.[257] On 1 October 1936, General Franco was confirmed head of state and armies in Burgos. A similar dramatic success for the Nationalists occurred on 17 October, when troops coming from Galicia relieved the besieged town of Oviedo, in Northern Spain.[258][259]

In October, the Francoist troops launched a major offensive toward Madrid,[260] reaching it in early November and launching a major assault on the city on 8 November.[261] The Republican government was forced to shift from Madrid to Valencia, outside the combat zone, on 6 November.[262] However, the Nationalists' attack on the capital was repulsed in fierce fighting between 8 and 23 November. A contributory factor in the successful Republican defense was the effectiveness of the Fifth Regiment[263] and later the arrival of the International Brigades, though only an approximate 3,000 foreign volunteers participated in the battle.[264] Having failed to take the capital, Franco bombarded it from the air and, in the following two years, mounted several offensives to try to encircle Madrid, beginning the three-year siege of Madrid. The Second Battle of the Corunna Road, a Nationalist offensive to the northwest, pushed Republican forces back, but failed to isolate Madrid. The battle lasted into January.[265]

1937

With his ranks swelled by Italian troops and Spanish colonial soldiers from Morocco, Franco made another attempt to capture Madrid in January and February 1937, but was again unsuccessful. The Battle of Málaga started in mid-January, and this Nationalist offensive in Spain's southeast would turn into a disaster for the Republicans, who were poorly organised and armed. The city was taken by Franco on 8 February.[266] The consolidation of various militias into the Republican Army had started in December 1936.[267] The main Nationalist advance to cross the Jarama and cut the supply to Madrid by the Valencia road, termed the Battle of Jarama, led to heavy casualties (6,000–20,000) on both sides. The operation's main objective was not met, though Nationalists gained a modest amount of territory.[268]

A similar Nationalist offensive, the Battle of Guadalajara, was a more significant defeat for Franco and his armies. This was the only publicised Republican victory of the war. Franco used Italian troops and blitzkrieg tactics; while many strategists blamed Franco for the rightists' defeat, the Germans believed it was the former at fault for the Nationalists' 5,000 casualties and loss of valuable equipment.[269] The German strategists successfully argued that the Nationalists needed to concentrate on vulnerable areas first.[270]

The "War in the North" began in mid-March, with the Biscay Campaign. The Basques suffered most from the lack of a suitable air force.[271] On 26 April, the Condor Legion bombed the town of Guernica, killing 200–300 and causing significant damage. The bombing of Guernica had a significant effect on international opinion. The Basques retreated from the area.[272]