Adrienne Lecouvreur | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Lecouvreur (ca. 1725), by anonymous artist, based on her first appearance at the Comédie-Française, and located in the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Châlons-en-Champagne | |

| Born | Adrienne Couvreur 5 April 1692 |

| Died | 20 March 1730 (aged 37) |

| Nationality | French |

| Employer | Comédie-Française |

| Partner | Maurice de Saxe |

Adrienne Lecouvreur (5 April 1692 – 20 March 1730[1]), born Adrienne Couvreur, was a French actress, considered by many as the greatest of her time.[2] Born in Damery, she first appeared professionally on the stage in Lille. After her Paris debut at the Comédie-Française in 1717, she was immensely popular with the public. Together with Michel Baron, she was credited for having developed a more natural, less stylized, type of acting.[3]

Despite the fame she gained as an actress and her innovations in her acting style, she was widely remembered for her romance with Maurice de Saxe[4] and for her mysterious death.[5] Although there are different theories that suggest she was poisoned by her rival, the Duchess of Bouillon, scholars have not been able to confirm it.[1]

Her story was used as an inspiration for playwrights, composers and poets. The refusal of the Catholic Church to give her a Christian burial moved her friend Voltaire to write a poem on the subject.

Life

Early years

Adrienne Lecouvreur was born on 5 April 1692, in the village of Damery in the province of Champagne. Her father, Robert Couvreur, was a hat maker who, in the hope of more lucrative opportunities, moved with his family to Paris. After the death of his wife, Marie Couvreur, Mr. Couvreur started frequenting taverns, leaving young Adrienne and her sister Marie Marguerite to fend for themselves.[2]

Young Adrienne found her own refuge watching rehearsals in the Comedie Francaise, and joining the rehearsals of a young, clandestine theater troupe that met in the back store of a grocer's shop on the rue Férou. The company premiered at the house of Madame de Gue, wife of a president of Parlement. They played Corneille's Polyeucte, with Adrienne Lecouvreur playing the role of Pauline.[4] Marc-Antoine Legrand, a sociétaire of the Comédie-Française, was present at this performance, and, impressed by her skills, took her as his pupil. Legrand also advised her to add the nobiliary particle "le" to her name.[2]

Lunéville

At age 14, Adrienne was already on tour.[1] Her first public performances as a professional actress took place in Lille, where Mademoiselle Fonpré, who had been appointed director of the theatre, was taken aback by Lecouvreur's potential. Shortly after her début, she started getting roles playing tragic queens and princesses. Her next engagements after Lille were in Lunéville, the capital of the Duchy of Lorraine. During this period, she had a daughter, Elisabeth-Adrienne, whose father was Philippe Le Roy, an officer who served the Duke Leopold of Lorraine.[2] She was also engaged to a man referred in her writings as "Baron D.", but he died in an accident before they could marry.[1]

Strasbourg

Shortly after Baron D's death, Adrienne Lecouvreur left Luneville, signing a contract with another theatre under the protection of the Duke of Lorraine; the theatre at Strasbourg.[2]

It was a time of great success for her. In Strasbourg, she met the young Count François de Klinglin, son of the city's chief magistrate. After months of visiting her, they announced their engagement, but one year into their commitment, Adrienne was expecting a second child. The shame of this impending wedding made the magistrate threaten his son with disinheritance, to which he gave in, calling off the engagement and agreeing to a new one, arranged by his family.[2]

In Strasbourg, Lecouvreur earned a considerable income. However, while she was relying on Baron D. and subsequently Klinglin's income beside her own, she incurred serious debt.[2] Her engagements as an actress required her to pay for her own wardrobe and jewelry, and actresses of Adrienne's status were subject to high expectations in their adornment.[4] Humiliated after Klinglin's arranged marriage, and with two children to support, Adrienne could no longer sustain herself in Strasbourg.

In 1716, at age 24, she left for Paris, and in 1717 she received a letter from the first gentleman of the King's chamber, requesting her to join the Comédie-Française. The letter read: "We, Steward and Controller General of the King's silverplate, pleasures, and business of the King's Chamber, order His Majesty's Players (in accordance with the order of Monseigneur the Duc d'Aumont, Peer of France and First Gentleman of the Chamber) to invite Mademoiselle Lecouvreur, immediately after the seasonal opening of their theatre, to perform in a play of her own choosing, in order to judge of any talent she may have for the theatre. Done in Paris this 27th day of March, 1717."[2]

Paris

Adrienne Lecouvreur chose Prosper Jolyot de Crébillon's Electre and Molière's George Dandin in the role of Angélique.[6] She made a surprising first appearance on stage. She wore a simple, white satin Grecian robe; not a heavily elaborated gown as was usual back then[2] — nor did she wear a heavy headdress, and her acting style was devoid of the typical artificial gestures of that time's declamatory style.[4]

In her first year (1717) she played Corneille and Racine (in particular the roles of Pulchérie in Heraclius, Monime, and Iphigénie), and Zenobia in Crébillon's play. In 1718 she played Aristie in Corneille's Sertorius and Atalide in Bajazet.[6] In total she gave 139 performances that season; an outstanding number for a beginner, and the most she would give throughout her career.[2]

Acting style

Adrienne Lecouvreur was one of the first actresses who favored a more natural, realistic and less declamatory style. She and actor Michel Baron sought for a style that was based on everyday speech, as opposed to the predominant chantante style of the time.[4] The playwright Pierre-François Godard de Beauchamps wrote on a letter to Mademoiselle Lecouvreur “Finally the true triumphs and the tragic furor give way, on the Stage, to the tender, the emotionally moving. You have made us know and feel the beauty of simplicity and its treasures.”[7] Charles Collé mentions the direct connection that Adrienne Lecouvreur created between the audience and the role itself: “She develops all the details of a role and makes us forget the actress. We see nothing but the character she represents.”[8]

Lecouvreur took this search for a more natural style into another aspect of her work, her wardrobe. Regardless of the era in which a play had been written, it was customary for actresses to wear elaborate dresses that reflected the fashion of the time, and sophisticated plumed headdresses.[4] Lecouvreur, however, made her first appearance at the Comedie Francaise wearing a simple Greek tunic in white satin to play Crebillon’s Electre.[2]

Legacy

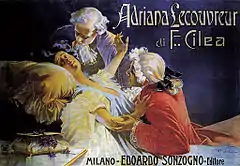

Her life became the inspiration for a tragic 1849 drama Adrienne Lecouvreur by Scribe and Legouvé on which Francesco Cilea's opera Adriana Lecouvreur and the operetta Adrienne (1926) by Walter Goetze[9] are based. Before them, however, in 1856, Edoardo Vera premiered his "dramma lirico" Adriana Lecouvreur e la duchessa di Bouillon.[10] In 1913 Sarah Bernhardt played her in the silent movie Adrienne Lecouvreur.[11] In 1928, MGM Studios filmed Dream of Love, based on the Scribe and Legouvé play, Adrienne Lecouvreur, starring Joan Crawford and Nils Asther. At least six further films were made based on her life including Adrienne Lecouvreur (1938).[12]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Commire, Anne; Klezmer, Deborah. "Lecouvreur, Adrienne (1690–1730)". Dictionary of Women Worldwide: 25,000 Women Through the Ages. Detroit: Yorkin Publications. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Richtman, Jack (1971). Adrienne Lecouvreur: the Actress and the Age. New Jersey: Englewood Cliffs. OCLC 1023756226.

- ↑ "Adrienne Lecouvreur". Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th Edition. Columbia University Press. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Scott, Virginia (2010). Women on the Stage in Early Modern France:1540-1750. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Probably from poison which was used almost in epidemic proportions during her era. See the chapter on the "Slow Poisoners" within Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds by Charles Mackay (pp. 565–592).

- 1 2 Tilley, Arthur (October 1922). "Tragedy at the Comédie-Française (1680-1778)". The Modern Language Review. 17 (4). doi:10.2307/3714277. JSTOR 3714277.

- ↑ Allainval, Abbé d' (1870). Lettre a Mylord *** sur Baron et la demoiselle Lecouvreur. Paris: L. Willem.

- ↑ Collé, Charles (1868). Journal et Mémoires sur les Hommes de lettres, les ouvrages dramatiques, et les événements les plus mémorables du regne de Louis XV. Paris: Firmin-Didot.

- ↑ Goebel, Wilfried. "Adrienne, von Goetze" (in German). operone. Retrieved 28 October 2007.

- ↑ Casaglia, Gherardo (2005)."Adriana Lecouvreur". L'Almanacco di Gherardo Casaglia (in Italian).

- ↑ Adrienne Lecouvreur (1913) at IMDb

- ↑ "Search IMDB for Adrienne Lecouvreur". Imdb.com. 1 May 2009. Retrieved 29 July 2014.