| Lucius Aelius | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caesar of the Roman Empire | |||||||||

Lucius Aelius, Louvre, Paris | |||||||||

| Born | 13 January 101 | ||||||||

| Died | 1 January 138 (aged 36) | ||||||||

| Spouse | Avidia | ||||||||

| Issue | Lucius Verus Ceionia Fabia Ceionia Plautia | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Father | Lucius Ceionius Commodus Hadrian (adoptive) | ||||||||

| Mother | Plautia | ||||||||

| Roman imperial dynasties | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.png.webp) | ||||||||||||||

| Nerva–Antonine dynasty (AD 96–192) | ||||||||||||||

| Chronology | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Family | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Succession | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

Lucius Aelius Caesar (13 January 101 – 1 January 138) was the father of Emperor Lucius Verus. In 136, he was adopted by the reigning emperor Hadrian and named heir to the throne. He died before Hadrian and thus never became emperor. After Lucius' death, he was replaced by Antoninus Pius, who succeeded Hadrian the same year.

Life and family

Aelius was born Lucius Ceionius Commodus, and became Lucius Aelius Caesar upon his adoption as Hadrian's heir. He is sometimes referred to as Lucius Aelius Verus, though this name is not attested outside the Historia Augusta, where it probably was originally the result of a manuscript error. The young Lucius Ceionius Commodus was of the gens Ceionia. His father, also named Lucius Ceionius Commodus (the Historia Augusta adds the cognomen Verus), was consul in 106, and his paternal grandfather, also of the same name, was consul in 78. His paternal ancestors were from Etruria, and were of consular rank. His mother is surmised to have been an undocumented Roman woman named Plautia.[1] The Historia Augusta states that his maternal grandfather and his maternal ancestors were of consular rank.

Before 130, the younger Lucius Commodus married Avidia, a well-connected Roman noblewoman who was the daughter of the senator Gaius Avidius Nigrinus. Avidia bore Lucius two sons and two daughters, who were:

- Lucius Ceionius Commodus the Younger – He would become Lucius Aurelius Verus, and would co-rule as Roman Emperor with Marcus Aurelius from 161 until his own death in 169. Verus would marry Lucilla, the second daughter of Marcus Aurelius and Faustina the Younger.

- Gaius Avidius Ceionius Commodus – he is known from an inscription found in Rome.

- Ceionia Fabia – at the time of Marcus Aurelius's adoption, she was betrothed, as part of the adoption conditions, to him. Shortly after Antoninus Pius' ascension, Pius came to Aurelius and asked him to end his engagement to Fabia, instead marrying Antoninus Pius’ daughter Faustina the Younger; Faustina had originally been planned by Hadrian to wed Lucius Verus.

- Ceionia Plautia

Heir to Hadrian

For a long time, the emperor Hadrian had considered his brother-in-law Lucius Julius Ursus Servianus as his unofficial successor. As Hadrian's reign drew to a close, however, he changed his mind. Although the emperor certainly thought Servianus capable of ruling as an emperor after Hadrian's own death, Servianus, by now in his nineties, was clearly too old for the position. Hadrian's attentions turned to Servianus' grandson, Lucius Pedanius Fuscus Salinator. Hadrian promoted the young Salinator, his great-nephew, gave him special status in his court, and groomed him as his heir.

However, in late 136, Hadrian almost died from a haemorrhage. Convalescent in his villa at Tivoli, he decided to change his mind, and selected Lucius Ceionius Commodus as his new successor, adopting him as his son.[2] The selection was done invitis omnibus, "against the wishes of everyone";[3] in particular, Servianus and the young Salinator became very angry at Hadrian and wished to challenge him over the adoption. Even today, the rationale for Hadrian's sudden switch is still unclear.[4][5] It is possible Salinator went so far as to attempt a coup against Hadrian in which Servianus was implicated. In order to avoid any potential conflict in the succession, Hadrian ordered the deaths of Salinator and Servianus.[6]

Although Lucius had no military experience, he had served as a senator, and had powerful political connections; however, he was in poor health. As part of his adoption, Lucius Ceionius Commodus took the name Lucius Aelius Caesar.

Death

After a year's stationing on the Danube frontier, Aelius returned to Rome to make an address to the senate on the first day of 138. The night before the speech, however, he grew ill, and died of a haemorrhage late the next day.[7][8][notes 1] On 24 January 138, Hadrian selected Titus Aurelius Antoninus as his new successor.[11][8]

After a few days' consideration, Antoninus accepted. He was adopted on 25 February 138. As part of Hadrian's terms, Antoninus adopted both Lucius Aelius's son, Lucius Ceionius Commodus, and Hadrian's great-nephew by marriage, Marcus Annius Verus. Marcus became "Marcus Aelius Aurelius Verus" (later Marcus Aurelius Antoninus); and Lucius became "Lucius Aelius Aurelius Commodus" (later Lucius Aurelius Verus).[notes 2] At Hadrian's request, Antoninus' daughter Faustina was betrothed to Lucius.[12]

Marcus Aurelius later co-ruled with Lucius Verus as joint Roman Emperors, until Lucius Verus died in 169, after which Aurelius was sole ruler until his own death in 180.

In his History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Edward Gibbon tells of Aelius's brief time as Hadrian's successor-designate in these terms:

After revolving in his mind several men of distinguished merit, whom he esteemed and hated, [Hadrian] adopted Ælius Verus a gay and voluptuous nobleman, recommended by uncommon beauty to the lover of Antinous. But whilst Hadrian was delighting himself with his own applause, and the acclamations of the soldiers, whose consent had been secured by an immense donative, the new Cæsar was ravished from his embraces by an untimely death.[13]

Sources

The major sources for the life of Aelius are patchy and frequently unreliable. The most important group of sources, the biographies contained in the Historia Augusta, claim to be written by a group of authors at the turn of the 4th century, but are in fact written by a single author (referred to here as "the biographer") from the later 4th century (c. 395).[14]

The later biographies and the biographies of subordinate emperors and usurpers are a tissue of lies and fiction, but the earlier biographies, derived primarily from now-lost earlier sources (Marius Maximus or Ignotus), are much more accurate.[14] For Aelius, the biographies of Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, Marcus and Lucius Verus are largely reliable, but that of Avidius Cassius, and even Lucius Aelius' own, is full of fiction.[15]

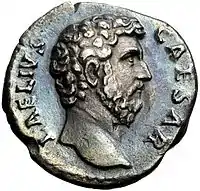

Some other literary sources provide specific detail: the writings of the physician Galen on the habits of the Antonine elite, the orations of Aelius Aristides on the temper of the times, and the constitutions preserved in the Digest and Codex Justinianus on Marcus' legal work. Inscriptions and coin finds supplement the literary sources.[16]

Nerva–Antonine family tree

| |

| Notes:

Except where otherwise noted, the notes below indicate that an individual's parentage is as shown in the above family tree.

| |

References:

|

Notes

All citations to the Historia Augusta are to individual biographies, and are marked with a "HA". Citations to the works of Fronto are cross-referenced to C.R. Haines' Loeb edition.

References

- ↑ Syme, Ronald (1957). "Antonine Relatives: Ceionii and Vettulani". Athenaeum, 35. pp. 306–315

- ↑ Birley 2000a, pp. 41–42.

- ↑ HA Hadrian 23.10, quoted in Birley 2000a, pp. 41–42

- ↑ Birley 2000a, p. 42.

- ↑ On the succession to Hadrian, see also: T.D. Barnes (1967) "Hadrian and Lucius Verus", Journal of Roman Studies 57(1–2): 65–79; J. VanderLeest (1995), "Hadrian, Lucius Verus, and the Arco di Portogallo", Phoenix 49(4) 319–30.

- ↑ Birley 2013, pp. 291–292.

- ↑ HA Hadrian 23.15–16; Birley 2000a, p. 45

- 1 2 Birley 2000b, p. 148.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 69.17.1; HA Aelius 3.7, 4.6, 6.1–7

- ↑ Birley 2000b, p. 147.

- ↑ Birley 2000a, p. 46.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 69.21.1; HA Hadrian 24.1; HA Aelius 6.9; HA Antoninus Pius 4.6–7; Birley 2000a, pp. 48–49.

- ↑ Gibbon, Edward (1845) [1782]. The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Vol.1, Ch. III, Part II.

- 1 2 Birley 2000a, pp. 229–230. The thesis of single authorship was first proposed in H. Dessau (1889) "Über Zeit und Persönlichkeit der Scriptoes Historiae Augustae" (in German), Hermes 24, 337ff.

- ↑ Birley 2000a, p. 230. On the HA Verus, see Barnes, 65–74.

- ↑ Birley 2000a, pp. 227–28.

Bibliography

- Birley, Anthony R. (2013). Hadrian: The Restless Emperor. Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 291–292. ISBN 978-0-415-16544-0.

- Birley, Anthony R. (2000a). Marcus Aurelius: A biography. Routledge. ISBN 9780415171250.

- Birley, Anthony R. (2000). "Hadrian to the Antonines". In Bowman, Alan K.; Garnsey, Peter; Rathbone, Dominic (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume XI: The High Empire, A.D. 70–192. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 132–94. ISBN 9780521263351.