| Lucius Verus | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Roman emperor | |||||||||

| Reign | 7 March 161 – 169 | ||||||||

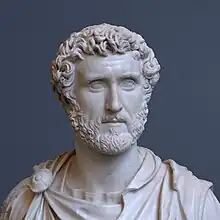

| Predecessor | Antoninus Pius | ||||||||

| Successor | Marcus Aurelius | ||||||||

| Co-emperor | Marcus Aurelius | ||||||||

| Born | 15 December 130 Rome, Italy | ||||||||

| Died | Early 169 (aged 38) Altinum, Italy | ||||||||

| Burial | |||||||||

| Spouse | |||||||||

| Issue | Aurelia Lucilla Lucilla Plautia Lucius Verus | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Dynasty | Nerva–Antonine | ||||||||

| Father |

| ||||||||

| Mother | Avidia | ||||||||

| Roman imperial dynasties | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nerva–Antonine dynasty (AD 96–192) | ||||||||||||||

| Chronology | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Family | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Succession | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

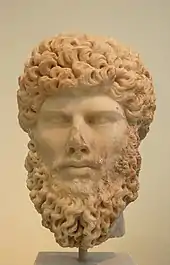

Lucius Aurelius Verus (15 December 130 – January/February 169) was Roman emperor from 161 until his death in 169, alongside his adoptive brother Marcus Aurelius. He was a member of the Nerva–Antonine dynasty. Verus' succession together with Marcus Aurelius marked the first time that the Roman Empire was ruled by more than one emperor simultaneously, an increasingly common occurrence in the later history of the Empire.

Born on 15 December 130, he was the eldest son of Lucius Aelius Caesar, first adopted son and heir to Hadrian. Raised and educated in Rome, he held several political offices prior to taking the throne. After his biological father's death in 138, he was adopted by Antoninus Pius, who was himself adopted by Hadrian. Hadrian died later that year, and Antoninus Pius succeeded to the throne. Antoninus Pius would rule the empire until 161, when he died, and was succeeded by Marcus Aurelius, who later raised his adoptive brother Verus to co-emperor.

As emperor, the majority of his reign was occupied by his direction of the war with Parthia which ended in Roman victory and some territorial gains. After initial involvement in the Marcomannic Wars, he fell ill and died in 169. He was deified by the Roman Senate as the Divine Verus (Divus Verus).

Early life, family, and career

Early life and family

Born Lucius Ceionius Commodus on 15 December 130, Verus was the first-born son of Avidia and Lucius Aelius Caesar, the first adopted son and heir of Emperor Hadrian.[2] He was born and raised in Rome. Verus had another brother, Gaius Avidius Ceionius Commodus, and two sisters, Ceionia Fabia and Ceionia Plautia.[2] His maternal grandparents were the senator Gaius Avidius Nigrinus and the unattested noblewoman Plautia. Although Hadrian was his adoptive paternal grandfather, his biological paternal grandparents were the consul Lucius Ceionius Commodus and either Aelia or Fundania Plautia.

Career

When his father died in early 138, Hadrian chose Antoninus Pius (86–161) as his successor. Antoninus was adopted by Hadrian on the condition that Verus and Hadrian's great-nephew Marcus Aurelius be adopted by Antoninus as his sons and heirs. By this scheme, Verus, who was already Hadrian's adoptive grandson through his natural father, remained as such through his new father, Antoninus. The adoption of Marcus Aurelius was probably a suggestion of Antoninus himself, since Marcus was the nephew of Antoninus' wife.

Immediately after Hadrian's death, Antoninus approached Marcus and requested that his marriage arrangements be amended: Marcus' betrothal to Ceionia Fabia would be annulled, and he would be betrothed to Faustina, Antoninus' daughter, instead. Faustina's betrothal to Ceionia's brother Lucius Commodus would also have to be annulled. Marcus consented to Antoninus' proposal.[3]

As a prince and future emperor, Verus received careful education from the famous grammaticus Marcus Cornelius Fronto. He was reported to have been an excellent student, fond of writing poetry and delivering speeches. Verus started his political career as a quaestor in 153, became consul in 154, and in 161 was consul again with Marcus Aurelius as his senior partner.

Emperor

Accession of Lucius and Marcus (161)

Antoninus died on 7 March 161, and was succeeded by Marcus Aurelius. Marcus Aurelius bore deep affection for Antoninus, as evidenced by the first book of Meditations.[4] Although the senate planned to confirm Marcus alone, he refused to take office unless Lucius received equal powers.[5]

The senate accepted, granting Lucius the imperium, the tribunician power, and the name Augustus.[6] Marcus became, in official titulature, Imperator Caesar Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus; Lucius, forgoing his name Commodus and taking Marcus's family name, Verus, became Imperator Caesar Lucius Aurelius Verus Augustus.[7][notes 1] It was the first time that Rome was ruled by two emperors.[8][notes 2]

In spite of their nominal equality, Marcus held more auctoritas, or authority, than Verus. He had been consul once more than Lucius, he had shared in Pius' administration, and he alone was Pontifex maximus. It would have been clear to the public which emperor was the more senior.[8] As the biographer wrote, "Verus obeyed Marcus...as a lieutenant obeys a proconsul or a governor obeys the emperor."[10]

Immediately after their senate confirmation, the emperors proceeded to the Castra Praetoria, the camp of the praetorian guard. Lucius addressed the assembled troops, which then acclaimed the pair as imperatores. Then, like every new emperor since Claudius, Lucius promised the troops a special donative.[11] This donative, however, was twice the size of those past: 20,000 sesterces (5,000 denarii) per capita, and more to officers. In return for this bounty, equivalent to several years' pay, the troops swore an oath to protect the emperors.[12] The ceremony was perhaps not entirely necessary, given that Marcus' accession had been peaceful and unopposed, but it was good insurance against later military troubles.[13]

Pius's funeral ceremonies were, in the words of the biographer, "elaborate".[14] If his funeral followed the pattern of past funerals, his body would have been incinerated on a pyre at the Campus Martius, while his spirit would rise to the gods' home in the heavens. Marcus and Lucius nominated their father for deification. In contrast to their behavior during Pius's campaign to deify Hadrian, the senate did not oppose the emperors' wishes.[15]

A flamen, or cultic priest, was appointed to minister the cult of the deified Pius, now Divus Antoninus. Pius's remains were laid to rest in Hadrian's mausoleum, beside the remains of Marcus's children and of Hadrian himself.[15] The temple he had dedicated to his wife, Diva Faustina, became the Temple of Antoninus and Faustina. It survives as the church of San Lorenzo in Miranda.[13]

Early rule (161–162)

Soon after the emperors' accession, Marcus's eleven-year-old daughter, Annia Lucilla, was betrothed to Lucius (in spite of the fact that he was, formally, her uncle).[16] At the ceremonies commemorating the event, new provisions were made for the support of poor children, along the lines of earlier imperial foundations.[17] Marcus and Lucius proved popular with the people of Rome, who strongly approved of their civiliter (lacking pomp) behavior.[18]

The emperors permitted free speech, evidenced by the fact that the comedy writer Marullus was able to criticize them without suffering retribution. At any other time, under any other emperor, he would have been executed. But it was a peaceful time, a forgiving time. And thus, as the biographer wrote, "No one missed the lenient ways of Pius."[18]

Fronto returned to his Roman townhouse at dawn on 28 March, having left his home in Cirta as soon as news of his pupils' accession reached him. He sent a note to the imperial freedman Charilas, asking if he could call on the emperors. Fronto would later explain that he had not dared to write the emperors directly.[19] The tutor was immensely proud of his students. Reflecting on the speech he had written on taking his consulship in 143, when he had praised the young Marcus, Fronto was ebullient: "There was then an outstanding natural ability in you; there is now perfected excellence. There was then a crop of growing corn; there is now a ripe, gathered harvest. What I was hoping for then, I have now. The hope has become a reality."[20] Fronto called on Marcus alone; neither thought to invite Lucius.[21]

Lucius was less esteemed by his tutor than his brother, as his interests were on a lower level. Lucius asked Fronto to adjudicate in a dispute he and his friend Calpurnius were having on the relative merits of two actors.[22] Marcus told Fronto of his reading—Coelius and a little Cicero—and his family. His daughters were in Rome, with their great-great-aunt Matidia Minor; Marcus thought the evening air of the country was too cold for them.[23]

The emperors' early reign proceeded smoothly. Marcus was able to give himself wholly to philosophy and the pursuit of popular affection.[24] Some minor troubles cropped up in the spring; there would be more later. In the spring of 162,[notes 3] the Tiber flooded over its banks, destroying much of Rome. It drowned many animals, leaving the city in famine. Marcus and Lucius gave the crisis their personal attention.[26][notes 4] In other times of famine, the emperors are said to have provided for the Italian communities out of the Roman granaries.[28]

War with Parthia (161–166)

Origins to Lucius's dispatch (161–162)

On his deathbed, Pius spoke of nothing but the state and the foreign kings who had wronged him.[29] One of those kings, Vologases IV of Parthia, made his move in late summer or early autumn 161.[30] Vologases entered the Kingdom of Armenia (then a Roman client state), expelled its king and installed his own—Pacorus, an Arsacid like himself.[31]

At the time of the invasion, the Governor of Syria was Lucius Attidius Cornelianus. Attidius had been retained as governor even though his term ended in 161, presumably to avoid giving the Parthians the chance to wrong-foot his replacement. The Governor of Cappadocia, the front-line in all Armenian conflicts, was Marcus Sedatius Severianus, a Gaul with much experience in military matters. But living in the east had a deleterious effect on his character.[32]

Severianus had fallen under the influence of Alexander of Abonoteichus, a self-proclaimed prophet who carried a snake named Glycon around with him, but was really only a confidence man.[33] Alexander was father-in-law to the respected senator Publius Mummius Sisenna Rutilianus, then-proconsul of Asia, and friends with many members of the east Roman elite.[34] Alexander convinced Severianus that he could defeat the Parthians easily, and win glory for himself.[35]

Severianus led a legion (perhaps the IX Hispana)[36] into Armenia, but was trapped by the great Parthian general Chosrhoes at Elegeia, a town just beyond the Cappadocian frontiers, high up past the headwaters of the Euphrates. Severianus made some attempt to fight Chosrhoes, but soon realized the futility of his campaign, and committed suicide. His legion was massacred. The campaign had only lasted three days.[37]

There was threat of war on other frontiers as well—in Britain, and in Raetia and Upper Germany, where the Chatti of the Taunus mountains had recently crossed over the limes.[38] Marcus was unprepared. Pius seems to have given him no military experience; the biographer writes that Marcus spent the whole of Pius's twenty-three-year reign at his emperor's side—and not in the provinces, where most previous emperors had spent their early careers.[39][notes 5] Marcus made the necessary appointments: Marcus Statius Priscus, the Governor of Britain, was sent to replace Severianus as Governor of Cappadocia.[41] Sextus Calpurnius Agricola took Priscus's former office.[42]

Strategic emergency

%252C_from_a_villa_belonging_to_Lucius_Verus_in_Acqua_Traversa_near_Rome%252C_between_AD_180_and_183_AD%252C_Louvre_Museum_(23450299872).jpg.webp)

More news arrived: Attidius Cornelianus's army had been defeated in battle against the Parthians, and retreated in disarray.[43] Reinforcements were dispatched for the Parthian frontier. Publius Julius Geminius Marcianus, an African senator commanding X Gemina at Vindobona (Vienna), left for Cappadocia with detachments from the Danubian legions.[44] Three full legions were also sent east: I Minervia from Bonn in Upper Germany,[45] II Adiutrix from Aquincum,[46] and V Macedonica from Troesmis.[47]

The northern frontiers were strategically weakened; frontier governors were told to avoid conflict wherever possible.[48] Attidius Cornelianus himself was replaced by Marcus Annius Libo, Marcus's first cousin. He was young—his first consulship was in 161, so he was probably in his early thirties[49]—and, as a mere patrician, lacked military experience. Marcus had chosen a reliable man rather than a talented one.[50]

Marcus took a four-day public holiday at Alsium, a resort town on the Etrurian coast. He was too anxious to relax. Writing to Fronto, he declared that he would not speak about his holiday.[51] Fronto replied ironically: "What? Do I not know that you went to Alsium with the intention of devoting yourself to games, joking and complete leisure for four whole days?"[52] He encouraged Marcus to rest, calling on the example of his predecessors (Pius had enjoyed exercise in the palaestra, fishing, and comedy),[53] going so far as to write up a fable about the gods' division of the day between morning and evening—Marcus had apparently been spending most of his evenings on judicial matters instead of at leisure.[54] Marcus could not take Fronto's advice. "I have duties hanging over me that can hardly be begged off," he wrote back.[55] Marcus put on Fronto's voice to chastise himself: "'Much good has my advice done you', you will say." He had rested, and would rest often, but "—this devotion to duty. Who knows better than you how demanding it is?"[56]

Fronto sent Marcus a selection of reading material, including Cicero's pro lege Manilia, in which the orator had argued in favor of Pompey taking supreme command in the Mithridatic War. It was an apt reference (Pompey's war had taken him to Armenia), and may have had some impact on the decision to send Lucius to the eastern front.[57] "You will find in it many chapters aptly suited to your present counsels, concerning the choice of army commanders, the interests of allies, the protection of provinces, the discipline of the soldiers, the qualifications required for commanders in the field and elsewhere [...][notes 6]"[59] To settle his unease over the course of the Parthian War, Fronto wrote Marcus a long and considered letter, full of historical references. In modern editions of Fronto's works, it is labeled De bello Parthico (On the Parthian War). There had been reverses in Rome's past, Fronto writes, at Allia, at Caudium, at Cannae, at Numantia, Cirta, and Carrhae;[60] under Trajan, Hadrian, and Pius;[61] but, in the end, Romans had always prevailed over their enemies: "always and everywhere [Mars] has changed our troubles into successes and our terrors into triumphs".[62]

Lucius's dispatch and journey east (162–163?)

.jpg.webp)

Over the winter of 161–62, as more troubling news arrived—a rebellion was brewing in Syria—it was decided that Lucius should direct the Parthian War in person. He was stronger and healthier than Marcus, the argument went, more suited to military activity.[63] Lucius's biographer suggests ulterior motives: to restrain Lucius's debaucheries, to make him thrifty, to reform his morals by the terror of war, to realize that he was an emperor.[64][notes 7] Whatever the case, the senate gave its assent, and Lucius left. Marcus remained in Rome; the city "demanded the presence of an emperor".[66]

Furius Victorinus, one of the two praetorian prefects, was sent with Lucius, as were a pair of senators, M. Pontius Laelianus Larcius Sabinus and M. Iallius Bassus, and part of the praetorian guard.[65] Victorinus had previously served as procurator of Galatia, giving him some experience with eastern affairs.[67][notes 8] Moreover, he was far more qualified than his praetorian partner, Cornelius Repentinus, who was said to owe his office to the influence of Pius's mistress, Galeria Lysistrate.[68] Repentinus had the rank of a senator, but no real access to senatorial circles—his was merely a decorative title.[69] Since a prefect had to accompany the guard, Victorinus was the clear choice.[68]

Laelianus had been governor of both Pannonias and Governor of Syria in 153; thus he had first-hand knowledge of the eastern army and military strategy on the frontiers. He was made comes Augustorum ("companion of the emperors") for his service.[70] Laelianus was, in the words of Fronto, "a serious man and an old-fashioned disciplinarian".[71] Bassus had been Governor of Lower Moesia, and was also made comes.[72] Lucius selected his favorite freedmen, including Geminus, Agaclytus, Coedes, Eclectus,[73] and Nicomedes, who gave up his duties as praefectus vehiculorum to run the commissariat of the expeditionary force.[67] The fleet of Misenum was charged with transporting the Emperor and general communications and transport.[74]

Lucius left in the summer of 162 to take a ship from Brundisium; Marcus followed him as far as Capua. Lucius feasted himself in the country houses along his route, and hunted at Apulia. He fell ill at Canosa, probably afflicted with a mild stroke, and took to bed.[75] Marcus made prayers to the gods for his safety in front of the senate, and hurried south to see him.[76] Fronto was upset at the news, but was reassured when Lucius sent him a letter describing his treatment and recovery. In his reply, Fronto urged his pupil to moderate his desires, and recommended a few days of quiet bedrest. Lucius was better after three days' fasting and a bloodletting.[77]

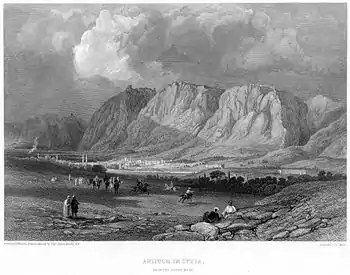

Verus continued eastward via Corinth and Athens, accompanied by musicians and singers as if in a royal progress.[78] At Athens he stayed with Herodes Atticus, and joined the Eleusinian Mysteries.[79] During sacrifice, a falling star was observed in the sky, shooting west to east.[80] He stopped in Ephesus, where he is attested at the estate of the local aristocrat Publius Vedius Antoninus,[81] and made an unexpected stopover at Erythrae.[82] The journey continued by ship through the Aegean and the southern coasts of Asia Minor, lingering in the famed pleasure resorts of Pamphylia and Cilicia, before arriving in Antioch.[83] It is not known how long Verus's journey east took; he might not have arrived in Antioch until after 162.[84] Statius Priscus, meanwhile, must have already arrived in Cappadocia; he would earn fame in 163 for successful generalship.[85]

Luxury and logistics at Antioch (162?–165)

%252C_inv._2217.JPG.webp)

Lucius spent most of the campaign in Antioch, though he wintered at Laodicea and summered at Daphne, a resort just outside Antioch.[86] He took up a mistress named Panthea,[notes 9] from Smyrna.[88] The biographer calls her a "low-born girl-friend",[89] but she was described as a "woman of perfect beauty" by Lucius. One biographer has postulated that Panthea may have been more beautiful than any of Phidias and Praxiteles' statues.[90] The mistress was musically inclined and spoke Ionic Greek, spiced with Attic wit.[91]

Panthea read Lucian's first draft, and criticized him for flattery. He had compared her to a goddess, which frightened her—she did not want to become the next Cassiopeia.[92] She had power, too. She made Lucius shave his beard for her. The Syrians mocked him for this, as they did for much else.[93]

Critics declaimed Lucius' luxurious lifestyle.[94] He had taken to gambling, they said; he would "dice the whole night through".[95] He enjoyed the company of actors.[96] He made a special request for dispatches from Rome, to keep him updated on how his chariot teams were doing.[97] He brought a golden statue of the Greens' horse Volucer around with him, as a token of his team spirit.[98] Fronto defended his pupil against some of these claims: the Roman people needed Lucius' bread and circuses to keep them in check.[99][notes 10]

This, at least, is how the biographer has it. The whole section of the vita dealing with Lucius' debaucheries (HA Verus 4.4–6.6) is an insertion into a narrative otherwise entirely cribbed from an earlier source. Some few passages seem genuine;[notes 11] others take and elaborate something from the original.[notes 12] The rest is by the biographer himself, relying on nothing better than his own imagination.[103]

Lucius faced quite a task. Fronto described the scene in terms recalling Corbulo's arrival one hundred years before.[104] The Syrian army had turned soft during the east's long peace. They spent more time at the city's open-air cafés than in their quarters. Under Lucius, training was stepped up. Pontius Laelianus ordered that their saddles be stripped of their padding. Gambling and drinking were sternly policed.[105] Fronto wrote that Lucius was on foot at the head of his army as often as on horseback. He personally inspected soldiers in the field and at camp, including the sick bay.[106]

Lucius sent Fronto few messages at the beginning of the war. He sent Fronto a letter apologizing for his silence. He would not detail plans that could change within a day, he wrote. Moreover, there was little thus far to show for his work: "not even yet has anything been accomplished such as to make me wish to invite you to share in the joy".[107] Lucius did not want Fronto to suffer the anxieties that had kept him up day and night.[108] One reason for Lucius' reticence may have been the collapse of Parthian negotiations after the Roman conquest of Armenia. Lucius' presentation of terms was seen as cowardice.[109] The Parthians were not in the mood for peace.[110]

Lucius needed to make extensive imports into Antioch, so he opened a sailing route up the Orontes. Because the river breaks across a cliff before reaching the city, Lucius ordered that a new canal be dug. After the project was completed, the Orontes' old riverbed dried up, exposing massive bones—the bones of a giant. Pausanias says they were from a beast "more than eleven cubits" tall; Philostratus says that it was "thirty cubits" tall. The oracle at Claros declared that they were the bones of the river's spirit.[111] These bones would later be understood to be that of several large unspecified animals.[112]

In the middle of the war, perhaps in autumn 163 or early 164, Lucius made a trip to Ephesus to be married to Marcus' daughter Lucilla.[113] Lucilla's thirteenth birthday was in March 163; whatever the date of her marriage, she was not yet fifteen.[114] Marcus had moved up the date: perhaps stories of Panthea had disturbed him.[115] Lucilla was accompanied by her mother Faustina and M. Vettulenus Civica Barbarus, the half-brother of Lucius' father.[116]

Marcus may have planned to accompany them all the way to Smyrna (the biographer says he told the senate he would); this did not happen.[117] Marcus only accompanied the group as far as Brundisium, where they boarded a ship for the east.[118] Marcus returned to Rome immediately thereafter, and sent out special instructions to his proconsuls not to give the group any official reception.[119] Lucilla would bear three of Lucius' children in the coming years. Lucilla became Lucilla Augusta.[120]

Counterattack and victory (163–166)

I Minervia and V Macedonica, under the legates M. Claudius Fronto and P. Martius Verus, served under Statius Priscus in Armenia, earning success for Roman arms during the campaign season of 163,[121] including the capture of the Armenian capital Artaxata.[122] At the end of the year, Verus took the title Armeniacus, despite having never seen combat; Marcus declined to accept the title until the following year.[123] When Lucius was hailed as imperator again, however, Marcus did not hesitate to take the Imperator II with him.[124] The army of Syria was reinforced by II Adiutrix and Danubian legions under X Gemina's legate Geminius Marcianus.[125]

Occupied Armenia was reconstructed on Roman terms. In 164, a new capital, Kaine Polis ('New City'), replaced Artaxata.[126] On Birley's reckoning, it was thirty miles closer to the Roman border.[115] Detachments from Cappadocian legions are attested at Echmiadzin, beneath the southern face of Mount Ararat, 400 km east of Satala. It would have meant a march of twenty days or more, through mountainous terrain, from the Roman border; a "remarkable example of imperialism", in the words of Fergus Millar.[127]

A new king was installed: a Roman senator of consular rank and Arsacid descent, Gaius Julius Sohaemus. He may not even have been crowned in Armenia; the ceremony may have taken place in Antioch, or even Ephesus.[128] Sohaemus was hailed on the imperial coinage of 164 under the legend Rex armeniis Datus: Verus sat on a throne with his staff while Sohaemus stood before him, saluting the emperor.[129]

In 163, while Statius Priscus was occupied in Armenia, the Parthians intervened in Osroene, a Roman client in upper Mesopotamia, just east of Syria, with its capital at Edessa. They deposed the country's leader, Mannus, and replaced him with their own nominee, who would remain in office until 165.[130] (The Edessene coinage record actually begins at this point, with issues showing Vologases IV on the obverse and "Wael the king" (Syriac: W'L MLK') on the reverse).[131] In response, Roman forces were moved downstream, to cross the Euphrates at a more southerly point.[110]

On the evidence of Lucian, the Parthians still held the southern, Roman bank of the Euphrates (in Syria) as late as 163 (he refers to a battle at Sura, which is on the southern side of the river).[132] Before the end of the year, however, Roman forces had moved north to occupy Dausara and Nicephorium on the northern, Parthian bank.[133][notes 13] Soon after the conquest of the north bank of the Euphrates, other Roman forces moved on Osroene from Armenia, taking Anthemusia, a town south-west of Edessa.[136] There was little movement in 164; most of the year was spent on preparations for a renewed assault on Parthian territory.[115]

Invasion of Mesopotamia (165)

In 165, Roman forces, perhaps led by Martius Verus and the V Macedonica, moved on Mesopotamia. Edessa was re-occupied, Mannus re-installed.[137] His coinage resumed, too: 'Ma'nu the king' (Syriac: M'NW MLK') or Antonine dynasts on the obverse, and 'King Mannos, friend of Romans' (Greek: Basileus Mannos Philorōmaios) on the reverse.[131] The Parthians retreated to Nisibis, but this too was besieged and captured. The Parthian army dispersed in the Tigris; their general Chosrhoes swam down the river and made his hideout in a cave.[138] A second force, under Avidius Cassius and the III Gallica, moved down the Euphrates, and fought a major battle at Dura.[139]

By the end of the year, Cassius' army had reached the twin metropolises of Mesopotamia: Seleucia on the right bank of the Tigris and Ctesiphon on the left. Ctesiphon was taken and its royal palace set to flame. The citizens of Seleucia, still largely Greek (the city had been commissioned and settled as a capital of the Seleucid Empire, one of Alexander the Great's successor kingdoms), opened its gates to the invaders. The city got sacked nonetheless, leaving a black mark on Lucius' reputation. Excuses were sought, or invented: the official version had it that the Seleucids broke faith first.[140] Whatever the case, the sacking marks a particularly destructive chapter in Seleucia's long decline.[141]

Cassius' army, although suffering from a shortage of supplies and the effects of a plague contracted in Seleucia, made it back to Roman territory safely.[142] Iunius Maximus, a young tribunus laticlavius serving in III Gallica under Cassius, took the news of the victory to Rome. Maximus received a generous cash bounty (dona) for bringing the good news, and immediate promotion to the quaestorship.[143] Lucius took the title Parthicus Maximus, and he and Marcus were hailed as imperatores again, earning the title 'imp. III'.[144] Cassius' army returned to the field in 166, crossing over the Tigris into Media. Lucius took the title 'Medicus',[145] and the emperors were again hailed as imperatores, becoming 'imp. IV' in imperial titulature. Marcus took the Parthicus Maximus now, after another tactful delay.[146]

Most of the credit for the war's success must be ascribed to subordinate generals. The forces that advanced on Osroene were led by M. Claudius Fronto, an Asian provincial of Greek descent who had led I Minervia in Armenia under Priscus. He was probably the first senator in his family.[147] Fronto was consul for 165, probably in honor of the capture of Edessa.[148] P. Martius Verus had led V Macedonica to the front, and also served under Priscus. Martius Verus was a westerner, whose patria was perhaps Tolosa in Gallia Narbonensis.[149]

The most prominent general, however, was C. Avidius Cassius, commander of III Gallica, one of the Syrian legions. Cassius was a young senator of low birth from the north Syrian town of Cyrrhus. His father, Heliodorus, had not been a senator, but was nonetheless a man of some standing: he had been Hadrian's ab epistulis, followed the emperor on his travels, and was prefect of Egypt at the end of Hadrian's reign. Cassius also, with no small sense of self-worth, claimed descent from the Seleucid kings.[150] Cassius and Martius Verus, still probably in their mid-thirties, took the consulships for 166.[151]

Vologases IV of Parthia (147–191) made peace but was forced to cede western Mesopotamia to the Romans.

Years in Rome

The next two years (166–168) were spent in Rome. Verus continued with his glamorous lifestyle and kept the troupe of actors and favourites with him. He had a tavern built in his house, where he celebrated parties with his friends until dawn. He also enjoyed roaming around the city among the population, without acknowledging his identity. The games of the circus were another passion in his life, especially chariot racing. Marcus Aurelius disapproved of his conduct but, since Verus continued to perform his official tasks with efficiency, there was little that he could do.

Wars on the Danube and death

In the spring of 168 war broke out in the Danubian border when the Marcomanni invaded the Roman territory. This war would last until 180, but Verus did not see the end of it. In 168, as Verus and Marcus Aurelius returned to Rome from the field, Verus fell ill with symptoms attributed to food poisoning, dying after a few days (169). However, scholars believe that Verus may have been a victim of smallpox, as he died during a widespread epidemic known as the Antonine Plague.

Despite the minor differences between them, Marcus Aurelius grieved the loss of his adoptive brother. He accompanied the body to Rome, where he offered games to honour his memory. After the funeral, the senate declared Verus divine to be worshipped as Divus Verus.

Nerva–Antonine family tree

| |

| Notes:

Except where otherwise noted, the notes below indicate that an individual's parentage is as shown in the above family tree.

| |

References:

|

See also

Notes

- ↑ These name-swaps have proven so confusing that even the Historia Augusta, the main source for the period, cannot keep them straight.[8] The fourth-century ecclesiastical historian Eusebius of Caesarea shows even more confusion.[9] The mistaken belief that Lucius had the name "Verus" before becoming emperor has proven especially popular.[8]

- ↑ There was, however, much precedent. The consulate was a twin magistracy, and earlier emperors had often had a subordinate lieutenant with many imperial offices (under Pius, the lieutenant had been Marcus). Many emperors had planned a joint succession in the past—Augustus planned to leave Gaius Caesar and Lucius Caesar as joint emperors on his death; Tiberius wished to have Gaius Caligula and Tiberius Gemellus do so as well; Claudius left the empire to Nero and Britannicus, imagining that they would accept equal rank—but all of these arrangements had ended in failure, either through premature death (Gaius and Lucius Caesar) or judicial murder (Gemellus by Caligula and Britannicus by Nero).[8]

- ↑ Because both Verus and Marcus are said to have taken active part in the recovery (HA Marcus 8.4–5), the flood must have happened before Verus's departure for the east in 162; because it appears in the biographer's narrative after Pius' funeral has finished and the emperors have settled into their offices, it must not have occurred in the spring of 161. A date in autumn 161 or spring 162 is probable, and, given the normal seasonal distribution of Tiber flooding, the most probable date is in spring 162.[25] (Birley dates the flood to autumn 161).[21]

- ↑ Since 15 CE, the river had been administered by a Tiber conservancy board, with a consular senator at its head and a permanent staff. In 161, the curator alevi Tiberis et riparum et cloacarum urbis (curator of the Tiber bed and banks and the city sewers") was A. Platorius Nepos, son or grandson of the builder of Hadrian's Wall, whose name he shares. He probably had not been particularly incompetent. A more likely candidate for that incompetence is Nepos' likely predecessor, M. Statius Priscus. A military man and consul for 159, Priscus probably looked on the office as little more than "paid leave".[27]

- ↑ Alan Cameron adduces the fifth-century writer Sidonius Apollinaris's comment that Marcus commanded "countless legions" vivente Pio (while Pius was alive) while contesting Birley's contention that Marcus had no military experience. (Neither Apollinaris nor the Historia Augusta (Birley's source) are particularly reliable on second-century history).[40]

- ↑ The text breaks off here.[58]

- ↑ Birley believes there is some truth in these considerations.[65]

- ↑ Victorinus had also served in Britain, on the Danube, in Spain, as prefect of the Italian fleets, as prefect of Egypt, and in many posts in Rome itself.[67]

- ↑ Or "Pantheia".[87]

- ↑ Fronto called it "the corn-dole and public spectacles" (annona et spectaculis), preferring his own pompous rephrase to Juvenal's plain panem et circenses.[100] (Fronto was, in any case, unfamiliar with Juvenal; the author was out of style through the classicizing mania of the Second Sophistic, and would not become popular until the later fourth century).[101]

- ↑ In the judgment of T.D. Barnes: 4.8, "He was very fond also of charioteers, favouring the 'Greens'."; 4.10, "He never needed much sleep, however; and his digestion was excellent."; perhaps 5.7, "After the banquet, moreover, they diced until dawn.".[102]

- ↑ In the judgment of T.D. Barnes: 4.8 ("He was very fond also of charioteers, favouring the 'Greens'.") and 10.9 ("Among other articles of extravagance he had a crystal goblet, named Volucer after that horse of which he had been very fond, that surpassed the capacity of any human draught.") are the seed for 6.2–6, "And finally, even at Rome, when he was present and seated with Marcus, he suffered many insults from the 'Blues,' because he had outrageously, as they maintained, taken sides against them. For he had a golden statue made of the 'Green' horse Volucer, and this he always carried around with him; indeed, he was wont to put raisins and nuts instead of barley in this horse's manger and to order him brought to him, in the House of Tiberius, covered with a blanket dyed with purple, and he built him a tomb, when he died, on the Vatican Hill. It was because of this horse that gold pieces and prizes first began to be demanded for horses, and in such honour was this horse held, that frequently a whole peck of gold pieces was demanded for him by the faction of the 'Greens'."; 10.8, "He was somewhat halting in speech, a reckless gambler, ever of an extravagant mode of life, and in many respects, save only that he was not cruel or given to acting, a second Nero.", for the comparison with other "bad emperors" at 4.6 ("...he so rivalled Caligula, Nero, and Vitellius in their vices..."), and, significantly, the excuse to use Suetonius.[102]

- ↑ The letter noting the victories (Ad Verum Imperator 2.1) dates to 164 (Fronto makes a reference to Marcus' delay in taking the Armeniacus; since he took the title in 164, the letter can be no earlier than that date),[134] but the battles themselves date to 163.[135]

Citations

- ↑ Cooley, Alison E. (2012). The Cambridge Manual of Latin Epigraphy. Cambridge University Press. p. 493. ISBN 978-0-521-84026-2.

- 1 2 Bishop, M. C. (2018). Lucius Verus and the Roman Defence of the East. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-4738-4945-7.

- ↑ HA Marcus 6.2; Verus 2.3–4; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 53–54.

- ↑ Marcus Aurelius, "Meditations", Book 1, 1.16

- ↑ HA Verus 3.8; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 116; "Hadrian to the Antonines", 156.

- ↑ HA Verus 4.1; Marcus 7.5; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 116.

- ↑ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 116–117.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 117; "Hadrian to the Antonines", 157 n.53.

- ↑ Birley, "Hadrian to the Antonines", 157 n.53.

- ↑ HA Verus 4.2, tr. David Magie, cited in Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 117, 278 n.4.

- ↑ HA Marcus 7.9; Verus 4.3; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 117–118.

- ↑ HA Marcus 7.9; Verus 4.3; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 117–118. "twice the size": Richard Duncan-Jones, Structure and Scale in the Roman Economy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), 109.

- 1 2 Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 118.

- ↑ HA Marcus 7.10, tr. David Magie, cited in Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 118, 278 n.6.

- 1 2 HA Marcus 7.10–11; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 118.

- ↑ HA Marcus 7.7; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 118.

- ↑ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 118, citing Werner Eck, Die Organisation Italiens (1979), 146ff.

- 1 2 HA Marcus 8.1, qtd. and tr. Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 119; "Hadrian to the Antonines", 157.

- ↑ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 120, citing Ad Verum Imperator 1.3.2 (= Haines 1.298ff).

- ↑ Ad Antoninum Imperator 4.2.3 (= Haines 1.302ff), qtd. and tr. Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 119.

- 1 2 Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 120.

- ↑ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 120, citing Ad Verum Imperator 1.1 (= Haines 1.305).

- ↑ Ad Antoninum Imperator 4.1 (= Haines 1.300ff), Marcus Aurelius, 120.

- ↑ HA Marcus 8.3–4; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 120.

- ↑ Gregory S. Aldrete, Floods of the Tiber in ancient Rome (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007), 30–31.

- ↑ HA Marcus 8.4–5; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 120.

- ↑ Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae 5932 (Nepos), 1092 (Priscus); Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 121.

- ↑ HA Marcus 11.3, cited in Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 278 n.16.

- ↑ HA Pius 12.7; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 114, 121.

- ↑ Event: HA Marcus 8.6; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 121. Date: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, "The Date of Lucian's Visit to Abonuteichos," Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 119 (1997): 281.

- ↑ HA Marcus 8.6; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 121.

- ↑ Lucian, Alexander 27; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 121.

- ↑ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 121. On Alexander, see: Robin Lane Fox, Pagans and Christians (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1986), 241–250.

- ↑ Lucian, Alexander 30; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 121.

- ↑ Lucian, Alexander 27; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 121–122.

- ↑ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 278 n.19.

- ↑ Dio 71.2.1; Lucian, Historia Quomodo Conscribenda 21, 24, 25; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 121–122.

- ↑ HA Marcus 8.7; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 122.

- ↑ HA Pius 7.11; Marcus 7.2; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 103–104, 122.

- ↑ Pan. Ath. 203–204, qtd. and tr. Alan Cameron, review of Anthony Birley's Marcus Aurelius, The Classical Review 17:3 (1967): 349.

- ↑ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 123, citing A.R. Birley, The Fasti of Roman Britain (1981), 123ff.

- ↑ HA Marcus 8.8; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 123, citing W. Eck, Die Satthalter der germ. Provinzen (1985), 65ff.

- ↑ HA Marcus 8.6; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 123.

- ↑ Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 8.7050–51; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 123.

- ↑ Incriptiones Latinae Selectae 1097–98; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 123.

- ↑ Incriptiones Latinae Selectae 1091; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 123.

- ↑ Incriptiones Latinae Selectae 2311; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 123.

- ↑ HA Marcus 12.13; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 123.

- ↑ L'Année Épigraphique 1972.657; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 125.

- ↑ HA Verus 9.2; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 125.

- ↑ De Feriis Alsiensibus 1 (= Haines 2.3); Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 126.

- ↑ De Feriis Alsiensibus 3.1 (= Haines 2.5), qtd. and tr. Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 126.

- ↑ De Feriis Alsiensibus 3.4 (= Haines 2.9); Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 126–127.

- ↑ De Feriis Alsiensibus 3.6–12 (= Haines 2.11–19); Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 126–127.

- ↑ De Feriis Alsiensibus 4, tr. Haines 2.19; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 127.

- ↑ De Feriis Alsiensibus 4 (= Haines 2.19), qtd. and tr. Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 127.

- ↑ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 127.

- ↑ De bello Parthico 10 (= Haines 2.31).

- ↑ De bello Parthico 10 (= Haines 2.31), qtd. and tr. Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 127.

- ↑ De bello Parthico 1 (= Haines 2.21).

- ↑ De bello Parthico 2 (= Haines 2.21–23); Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 127.

- ↑ De bello Parthico 1 (= Haines 2.21), qtd. and tr. Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 127.

- ↑ Dio 71.1.3; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 123.

- ↑ HA Verus 5.8; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 123, 125.

- 1 2 Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 125.

- ↑ HA Marcus 8.9, tr. Magie; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 123.

- 1 2 3 Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 125, citing H.G. Pflaum, Les carrières procuratoriennes équestres sous le Haut-Empire romain I–III (Paris, 1960–61); Supplément (Paris, 1982), no. 139.

- 1 2 HA Pius 8.9; Birley, "Hadrian to the Antonines", 160–161.

- ↑ Giuseppe Camodeca, "La carriera del prefetto del pretorio Sex.Cornelius Repentinus in una nuova iscrizione puteolana" (in Italian), Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 43 (1981): 47.

- ↑ Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae 1094, 1100; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 125.

- ↑ Ad Verum Imperator 2.6 (= Haines 2.84ff), qtd. and tr. Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 125.

- ↑ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 125, citing Prosopographia Imperii Romani2 1.4.

- ↑ HA Verus 8.6, 9.3–5; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 125.

- ↑ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 125, citing C.G. Starr, The Roman Imperial Navy, (1941), 188ff.

- ↑ HA Verus 6.7–9; HA Marcus 8.10–11; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 125–126. Stroke: Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 126; Haines 2.85 n. 1.

- ↑ HA Marcus 8.11; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 125–126.

- ↑ Ad Verum Imperator 2.6 (= Haines 2.85–87); Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 125–126.

- ↑ HA Verus 6.9; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 126; "Hadrian to the Antonines", 161.

- ↑ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 126, citing SIG3 1.869, 872; HA Hadrian 13.1.

- ↑ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 126, citing Cassiodorus senator s.a. 162.

- ↑ Birley, "Hadrian to the Antonines", 161, citing I Eph 728, 3072; H. Halfmann, Itinera Principum. Geschichte und Typologie der Kaiserreisen im Römischen Reich (Stuttgart, 1986), 210–211.

- ↑ Christian Habicht, "Pausanias and the Evidence of Inscriptions", Classical Antiquity 3:1 (1984), 42–43, citing IErythrai 225.

- ↑ HA Verus 6.9; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 126.

- ↑ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 126; "Hadrian to the Antonines", 161.

- ↑ Dio 71.3.1; HA Verus 7.1; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 126.

- ↑ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 129.

- ↑ Barry Baldwin, review of C.P. Jones' Culture and Society in Lucian, American Historical Review 92:5 (1987), 1185.

- ↑ Smyrna: Lucian, Imagines 2; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 129.

- ↑ HA Verus 7.10, qtd. and tr. Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 129.

- ↑ Lucian, Imagines 3, qtd. and tr. Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 129.

- ↑ Lucian, Imagines 11, 14–15; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 129.

- ↑ Lucian, Pro Imaginibus 7; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 129.

- ↑ HA Verus 7.10, cf. 7.4; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 129.

- ↑ HA Verus 4.4; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 129.

- ↑ HA Verus 4.6, tr. Magie; cf. 5.7; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 129.

- ↑ HA Verus 8.7, 8.10–11; Fronto, Principae Historia 17 (= Haines 2.217); Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 129.

- ↑ HA Verus 6.1; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 129.

- ↑ HA Verus 6.3–4; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 129.

- ↑ Principae Historiae 17 (= Haines 2.216–17); Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 129.

- ↑ Principae Historiae 17 (= Haines 2.216–217); Juvenal, 10.78; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 129.

- ↑ Alan Cameron, "Literary Allusions in the Historia Augusta", Hermes 92:3 (1964), 367–368.

- 1 2 Barnes, 69. Translations from the HA Verus: Magie, ad loc.

- ↑ Barnes, 69.

- ↑ Birley, "Hadrian to the Antonines", 162.

- ↑ Ad Verum Imperator 2.1.19 (= Haines 2.149); Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 129.

- ↑ Principae Historia 13 (= Haines 2.209–211); Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 129–130.

- ↑ Ad Verum Imperator 2.2 (= Haines 2.117), tr. Haines; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 130; "Hadrian to the Antonines", 162.

- ↑ Ad Verum Imperator 2.2 (= Haines 2.117–119); Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 130; "Hadrian to the Antonines", 162.

- ↑ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 130; citing Panegyrici Latini 14(10).6.

- 1 2 Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 130; "Hadrian to the Antonines", 162.

- ↑ Pausanias 8.29.3–4; Philostratus, Heroicus 138.6–9 K., 9.5–7 L.; Christopher Jones, "The Emperor and the Giant", Classical Philology 95:4 (2000): 476–481.

- ↑ Mayor, Adrienne (2011). The First Fossil Hunters: Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and Myth in Greek and Roman Times. Princeton University Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0691150130.

- ↑ HA Verus 7.7; Marcus 9.4; Barnes, 72; Birley, "Hadrian to the Antonines", 163; cf. also Barnes, "Legislation Against the Christians", Journal of Roman Studies 58:1–2 (1968), 39; "Some Persons in the Historia Augusta", Phoenix 26:2 (1972), 142, citing the Vita Abercii 44ff.

- ↑ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 131; "Hadrian to the Antonines", 163.

- 1 2 3 Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 131.

- ↑ HA Verus 7.7; Marcus 9.4; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 131.

- ↑ HA Verus 7.7; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 131.

- ↑ HA Marcus 9.4; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 131.

- ↑ HA Marcus 9.5–6; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 131.

- ↑ Birley, "Hadrian to the Antonines", 163.

- ↑ Birley, "Hadrian to the Antonines", 161–162, citing Prosopographia Imperii Romani2 C 874 (Claudius Fronto); Prosopographia Imperii Romani2 M 348.

- ↑ HA Marcus 9.1; Birley, "Hadrian to the Antonines", 162.

- ↑ HA Marcus 9.1; HA Verus 7.1–2; Ad Verrum Imperator 2.3 (= Haines 2.133); Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 129; "Hadrian to the Antonines", 162.

- ↑ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 129; "Hadrian to the Antonines", 162, citing H. Mattingly, Coins of the Roman Empire in the British Museum IV: Antoninus Pius to Commodus (London, 1940), Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus, nos. 233ff.

- ↑ Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae 8977 (II Adiutrix); Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 8.7050–51 (Marcianus); Birley, "Hadrian to the Antonines", 162.

- ↑ Dio 71.3.1; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 131; "Hadrian to the Antonines", 162; Millar, Near East, 113.

- ↑ Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae 394; 9117; Millar, Near East, 113.

- ↑ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 280 n. 42; "Hadrian to the Antonines", 162.

- ↑ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 131; "Hadrian to the Antonines", 162, citing H. Mattingly, Coins of the Roman Empire in the British Museum IV: Antoninus Pius to Commodus (London, 1940), Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus, nos. 261ff.; 300 ff.

- ↑ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 130, 279 n. 38; "Hadrian to the Antonines", 163, citing Prosopographia Imperii Romani2 M 169.

- 1 2 Millar, Near East, 112.

- ↑ Lucian, Historia Quomodo Conscribenda 29; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 130; "Hadrian to the Antonines", 162.

- ↑ Fronto, Ad Verum Imperator 2.1.3 (= Haines 2.133); Astarita, 41; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 130; "Hadrian to the Antonines", 162.

- ↑ Champlin, "Chronology", 147.

- ↑ Astarita, 41; Birley, "Hadrian to the Antonines", 162.

- ↑ Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae 1098; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 130.

- ↑ Birley, "Hadrian to the Antonines", 163, citing Prosopographia Imperii Romani2 M 169.

- ↑ Lucian, Historia Quomodo Conscribenda 15, 19; Birley, "Hadrian to the Antonines", 163.

- ↑ Lucian, Historia Quomodo Conscribenda 20, 28; Birley, "Hadrian to the Antonines", 163, citing Syme, Roman Papers, 5.689ff.

- ↑ HA Verus 8.3–4; Birley, "Hadrian to the Antonines", 163. Birley cites R.H. McDowell, Coins from Seleucia on the Tigris (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1935), 124ff., on the date.

- ↑ John F. Matthews, The Roman Empire of Ammianus (London: Duckworth, 1989), 142–143. Birley, "Hadrian to the Antonines", 163–164, says that the siege marked the end of the city's history.

- ↑ Birley, "Hadrian to the Antonines", 164.

- ↑ Birley, "Hadrian to the Antonines", 164, citing Alföldy and Halfmann, "Iunius Mauricus und die Victoria Parthica", Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 35 (1979): 195–212 = Alföldy, Römische Heeresgeschichte. Beiträge 1962–1985 (Amsterdam, 1987), 203 ff (with addenda, 220–221); Fronto, Ad amicos 1.6.

- ↑ Birley, "Hadrian to the Antonines", 164, citing H. Mattingly, Coins of the Roman Empire in the British Museum IV: Antoninus Pius to Commodus (London, 1940), Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus, nos. 384 ff., 1248 ff., 1271 ff.

- ↑ Birley, "Hadrian to the Antonines", 164, citing P. Kneissl, Die Siegestitulatur der römischen Kaiser. Untersuchungen zu den Siegerbeinamen des 1. und 2. Jahrhunderts (Göttingen, 1969), 99 ff.

- ↑ Birley, "Hadrian to the Antonines", 164, citing H. Mattingly, Coins of the Roman Empire in the British Museum IV: Antoninus Pius to Commodus (London, 1940), Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus, nos. 401ff.

- ↑ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 130, citing Prosopographia Imperii Romani2 C 874.

- ↑ Birley, "Hadrian to the Antonines", 164, citing Alföldy, Konsulat, 179 ff.

- ↑ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 130, citing Prosopographia Imperii Romani2 M 348.

- ↑ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 130, citing Prosopographia Imperii Romani2 A 1402f.; 1405; Astarita, passim; Syme, Bonner Historia-Augustia Colloquia 1984 (= Roman Papers IV (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988), ?).

- ↑ Birley, "Hadrian to the Antonines", 164, citing Alföldy, Konsulat, 24, 221.

- ↑ Michael Grant (1994). The Antonines: The Roman Empire in Transition. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415107547, pp. 27–28.