A transformational growth in aerial reconnaissance occurred in the years 1939–45, especially in Britain and then in the United States. It was an expansion determined mostly by trial and error, represented mostly by new tactics, new procedures, and new technology, though rarely by specialized aircraft types. The mission type branched out into many sub-types, including new electronic forms of reconnaissance. In sharp contrast with the case during the pre-war years, by 1945 air reconnaissance was widely recognized as a vital, indispensable component of air power.

Pre-war situation

In the interwar years, reconnaissance languished as a mission type and tended to be overshadowed by routine aerial mapping. This was despite the growth (in the United States and Britain) of a doctrine of strategic bombardment as the decisive weapon of war. Experience would soon prove that bombing was completely ineffective unless accompanied by intensive aerial reconnaissance. In the 1930s, gradual technical progress in the leading air nations led to advances particularly in photogrammetry and cartography, but failed to be translated into a capable operational reconnaissance capability. The various parties went into the new war with mostly the same cameras and procedures they had used when exiting the last one. Stereoscopic imaging using overlapping exposures was refined and standardized for mapping.[1] Color photography from the air was introduced in 1935 in the United States, but did not find widespread application.[2] Experiments with flash bomb photography at night were carried out pre-war, but did not lead to an operational capability until later in the war.[3] In the United States, apart from the case of small army-cooperation observation planes, the emphasis was almost completely on aerial mapping conducted by long-range bombers. In Germany, the Army Chief, Werner Freiherr von Fritsch, noted that in the next war, whoever had the best air reconnaissance would win – and thereby won himself a perfunctory mention in almost all subsequent works on the topic.[4] Yet in all countries, initial doctrines were focused on battlefield observation, which assumed a relatively static front, as it had been in the previous war.[5]

Strategic reconnaissance in its embryonic form began with the flights carried out over Germany by Australian businessman Sidney Cotton just before the outbreak of war in Europe. On behalf of first French and then British intelligence, Cotton outfitted civilian Lockheed Electras with hidden cameras and was able to snap useful footage during business trips. Cotton pioneered (for the British) the trimetrogon mount and the important innovation of heated cameras, fogging being the bane of high-altitude photography.[6] However, a multi-lens trimetrogon had been used in the 1919 U.S. Bagley mapping camera, and Germany had heated optics during the Great War.[7]

Early Western reconnaissance

Sidney Cotton's work found only grudging approval with the Royal Air Force, but eventually his work was incorporated into No. 1 Photographic Development Unit (PDU) at RAF Heston and then RAF Benson, a unit from which most later British air reconnaissance developed. (It soon was renamed 1 PRU, R for reconnaissance.)[8] Key to the RAF's intellectual ascendancy in reconnaissance was the establishment of the Central Interpretation Unit (CIU) at RAF Medmenham. Priority tasks of this unit were to prepare target folders and to chart Axis air defenses. In short order, it began to evaluate the effectiveness of bombing.[9] See Photo interpretation.

At first Britain used a handful of hastily modified Spitfires (PR 1) and some medium twins (Bristol Blenheims) for photographic reconnaissance, supplemented by in-action footage shot from regular bombing aircraft. At this time the RAF still used the vintage F8 and F24 cameras, later adding the larger F52. The F24 became especially useful in night photography.[10] Thanks to bomb damage assessment (BDA) the complete failure of precision daylight bombing soon became apparent, the vast majority of bombers not even coming close to their targets. This resulted in heavier demands on reconnaissance for before-and-after photography; and the documented poor results (as well as heavy losses) led to a shift to night-time area bombing.[11]

Britain was far behind Germany in optics, and at one time 1 PRU took two Zeiss Ikon cameras with 60 cm lenses from a lost Ju 88 and used them for high-altitude photography.[12]

By 1941, the RAF had a capable reconnaissance arm (1 PRU) centered at RAF Benson, supported by a nascent infrastructure in interpretation and analysis. The Combined/Joint Intelligence Committee (CIC) ensured centralized tasking for critical objectives. The RAF led this field by far, and in 1941 several American observers from both the U.S. Army Air Corps (USAAC) and the U.S. Navy were sent to England to investigate RAF reconnaissance methods.[13]

Unlike the case in the previous war, French reconnaissance was now comparatively ineffective on all levels, and entirely lacked a strategic perspective. Most aircraft allocated to the mission type were obsolete. Large numbers of open-cockpit Mureaux 115/117 and light twin Potez 630 series were assigned to Army cooperation according to observation doctrines from the previous war. However, the new and scarce Bloch 174 twin distinguished itself by its high performance. Noted writer and reconnaissance pilot Antoine de Saint-Exupéry flew this aircraft before the fall of France.[14]

Italian reconnaissance over Ethiopia

The Istituto Geografico Militare acquired aerial photographs to sustain its war effort against Ethiopia in the mid 1930s. The aerial photographs over Ethiopia in 1935-1941 consist of 8281 assemblages on hardboard tiles, each holding a label, one nadir-pointing photograph flanked by two low-oblique photographs and one high-oblique photograph. The four photos were exposed simultaneously and were taken across the flight line. A high-oblique photograph is presented alternatively at left and at right. There is approx. 60% overlap between subsequent sets of APs. One of Ermenegildo Santoni's glass plate multi-cameras was used, with focal length of 178 mm and with a flight height of 4000–4500 metres above sea level, which resulted in an approximate scale of 1:11,500 for the central photograph and 1:16,000 to 1:18,000 for the low-oblique photos. The surveyors oriented themselves with maps of Ethiopia at 1:400,000 scale, compiled in 1934. The flights present a dense coverage of Northern Ethiopia, where they were acquired in the context of the Second Italo-Ethiopian War. Several flights preceded the later advance of the Italian army southwards to the capital Addis Ababa. As of 1936, the aerial photographs were used to prepare topographic maps at 1:100,000 and 1:50,000 scales.[15][16]

German reconnaissance capabilities

Despite a considerable technological and numerical head start, Germany gradually neglected aerial reconnaissance, at least relative to Britain. The reason, grounded in history and geography, was that Germany had no strategic bombing doctrine and viewed air power as an auxiliary of land armies. Numerous Aufklärungs (up-clearing, i.e. reconnaissance) units were established for marine and ground support purposes, but while this was effective in the tactical sense, the intellectual investment in interpretation, analysis, and strategic estimation lagged. From the German perspective, this was defensible considering that about 90% of the action lay in large land-battles in the East, and an expensive long-range air capability would have been unlikely to effectively change the outcome.[17]

Leading up to the war, the United States developed an indigenous high-quality optics capability led by Bausch & Lomb of Rochester, N.Y.; however this company had been allied to Germany's Zeiss-Jena. Nonetheless, the American reconnaissance expert, Captain George Goddard, said that he much coveted German technical leadership, specifically as represented by Carl Zeiss Jena optical works, and he was pleased to briefly occupy that facility at the end of the war. The Luftwaffe (German Air Force), expecting a quick victory, did not build an integrated reconnaissance and interpretation capability like the Anglo Allies did.[18]

Before 22 June 1941, German reconnaissance was far predominant in frequency with many daily sorties throughout the region. Leading up to the invasion of France, concentration was on ports, forts, railways and airports, using mostly Dornier Do 17Ps and Heinkel He 111Hs, already vulnerable types, and rapid conversion to Junkers Ju 88D, later Ju 88H followed. Losses were on the order of 5–10 per cent. A regular daily weather reconnaissance was kept up over the North Sea. Maritime reconnaissance from France and Norway reached well west of Ireland to the coast of Greenland using Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor and various multi-engine seaplanes.[19] Germany used the LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin airship for signals intelligence sorties targeting RAF radar stations in 1939.

German units were divided into Fernaufklärer (long-distance), Nahaufklärer (tactical, subordinate to Army command), Nachtaufklärer (night photography) and maritime and special units. Command structure and unit designations changed incessantly. Each staffel (squadron, roughly) had a Bildgruppe of interpreters, who would telephone urgent intelligence to nearby headquarters. Film and analyses would go to Fliegerkorps (higher-level) staff later; eventually top-level staff at the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW) headquarters at Zossen near Berlin would receive the products for filing and possibly strategic integration.[20]

Germany emphasized tactical reconnaissance and invested considerably in modified aircraft – primarily Ju 88s and Junkers Ju 188s – and in types such as the asymmetric Blohm & Voss BV 141 (20 built) and the twin-boom Focke-Wul Fw 189 Uhu (nearly 900 produced). This Nahaufklärung was primarily successful on the Eastern Front where immediate results were desired, and these units were directly under Army field command. For special demanding tasks a high-altitude photographic reconnaissance aircraft, the pressurized Junkers Ju 86P was available in very small numbers, but it could not survive after 1943. Also pressurized, the Junkers Ju 388L could reach 45,000 ft (14,000 m) and much higher airspeeds than the Ju 86P but only 50 examples were built late in the war and few saw operational service. Fighters, often with dual oblique cameras in the rear fuselage, were pressed into service for reconnaissance where their speed was necessary and performed well in this role. German reconnaissance against well-defended England was relatively ineffective.[21]

Prior to Operation Barbarossa, the German attack on the USSR, the Luftwaffe carried out extensive aerial observation of European Russia. This was possible partly because Soviet air opposition was weak, and because of the Soviet leadership's conviction that Germany would not attack. The Luftwaffe maintained air superiority in the East until late in the war, but simply could not bring enough resources to bear for air power to be decisive.[22] Italy and Japan, performed long-distance reconnaissance prior to meeting stiffening opposition in 1942. Japanese aircraft reconnoitered the Philippines prior to 7 December 1941.[23]

Other countries

The Soviet Union had no advanced reconnaissance resources, but emphasized visual observation and reporting over the battle space. Open-cockpit biplanes such as the Polikarpov Po-2 were very useful for this, especially at night. The Soviets had virtually no interest in long-range air power or strategic reconnaissance, and had no advanced optics capabilities. However, they learned a lot about the discipline from the Americans when the U.S. Army Air Forces operated from three Ukrainian bases in 1944 (Operation Frantic). This operation included a photo-reconnaissance detachment which shared all results with the USSR. At the same time, Americans learned that Soviet photographic reconnaissance capabilities were embryonic.[24]

Japanese reconnaissance was characterized by institutional rivalry between the Army and the Navy. The latter standardized on the Yokosuka D4Y Suisei ("Judy") and Nakajima C6N ("Myrt") multi-seat aircraft. The Army, which encountered little air opposition in China, used a variety of aircraft types and cameras.

Italy entered the war in 1940 with a very large number of obsolete observation aircraft, mostly open-cockpit biplanes assigned directly to Army commands. Initially, some strategic surveillance was carried out by three-engined bombers, and Italian aircraft ranged from Nigeria to Abyssinia to Bahrein (one flew to Japan and back). Italian reconnaissance could not survive in contested airspace.

Neutral countries seemingly remained in the World War I mindset of trench observation. While aerial photography was allocated to tactically inferior aircraft, and aerial mapping advanced considerably, there was no concept of strategic reconnaissance and little thought given to analysis and interpretation. Surprisingly, this was even the case in the United States, where the Air Corps had staked its future on the doctrine of strategic bombing. Up to 1940, the USAAC's interest in reconnaissance was centered in one small office at Wright Field, Ohio, headed by the controversial Captain George William Goddard. He was responsible for most of the technical advantages adopted by the USAAC during the early war years. The extensive O-series of aircraft, such as the Douglas O-38 and its descendants, were typically low and slow and used for direct Army liaison, artillery spotting, and observation. The OA series of observation amphibians were mostly Army variants of better known Navy types, such as the Consolidated PBY Catalina. These were in practice more utility aircraft than dedicated reconnaissance platforms. In December 1941, complacency and inadequate leadership led to the failure to detect the Japanese task force north of Hawaii from the air.[25] Also, the Americans labored under the handicap that much equipment was assigned to Britain as fast as it could be produced.

American contribution

By 1941, prompted by the British experience, Americans began to understand the need for a much expanded air reconnaissance concept. The F-series, which denoted photographic reconnaissance, was then led by the F-3A, a modified Douglas A-20 Havoc light bomber. Thanks in large part to the advocacy of the Director of Photographic Intelligence, the also very controversial Colonel Minton Kaye, a run of 100 Lockheed P-38 Lightnings were set aside for modification to F-4 standard, incorporating the trigonometric mount that both Kaye and Cotton had pioneered prior to the war. Despite the promising performance of the F-4, there were so many technical problems with the early versions that the model was largely rejected by its crews when it did reach combat zones. The RAF rejected the P-38, as well.[26]

The first U.S. operational reconnaissance experience was gained in the Australian theater. The top name to emerge was that of Colonel Karl Polifka, an extremely aggressive pilot who developed many of the tactics that would later become standard. Operating from Port Moresby to Rabaul, his F-4-equipped 8th PR squadron encountered serious problems reducing it at one time to one aircraft, but the valuable experience gained was shared by Polifka when he returned to the U.S. in 1943.[27]

When the United States and Britain invaded French North Africa in November 1942, the hastily improvised reconnaissance capability was quickly checked by reality. President Franklin D. Roosevelt's son, Colonel Elliott Roosevelt, led the American reconnaissance assets and in February joined with RAF units in the multinational Northwest African Photographic Reconnaissance Wing (NAPRW). At that point the Wing had found the F-4 unsatisfactory, the F-9 or Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress unable to survive over enemy territory, and the new British de Havilland Mosquito to be the most promising reconnaissance platform. British squadrons in the Mediterranean took over the slack left by the Americans. Numerous other technical and tactical problems virtually brought American reconnaissance to a halt; but it rebounded swiftly, and by the time of the invasion of Sicily in July (Operation Husky), a very credible joint capability existed, the NAPRW comprising South African, Free French, and New Zealand units as well as RAF and USAAC units. By that time, new F-5 models of the Lightning were becoming available, and they were found to be far more reliable and capable.[28] However, this period marked the beginning of a year-long struggle by the USAAF, led especially by Colonel Roosevelt, to acquire the Mosquito and to also develop a brand new reconnaissance aircraft – a quest that would result in the ill-fated and scandal-ridden Hughes XF-11.[29]

The RAF continued to display leadership in the field, and now took on the role of on-the-job mentor to the Americans. Supermarine Spitfires and Mosquitos were found to be the best reconnaissance platforms, as everyone now realized that speed, range, and altitude were essential to survival and good photographs. Second-line photographic aircraft (such as Douglas Bostons, Bristol Blenheims, Martin Marylands) were relegated to less contested skies. The RAF turned Medmenham into the Allied Central Interpretation Unit (ACIU), inviting the Americans to participate on a joint basis, and continued to spin off new squadrons with high-performance reconnaissance aircraft based both in the British Isles and in the Mediterranean. Other RAF units operated in the Far East, often with slightly less capable aircraft such as Hawker Hurricanes and North American B-25 Mitchells.

A very large fraction of RAF reconnaissance was consumed in tracking German capital ships. This endeavor even included stationing photo detachments at Vaenga airfield on the Kola Peninsula. When the British returned home, their reconnaissance aircraft were given to the Soviets.[30]

During this period Wing Commander Adrian Warburton built a reputation as a daring and productive reconnaissance pilot; and Wing Commander D. W. Steventon undertook many important missions, inc. some of the first overflights of the German experimental site of Peenemünde Army Research Center on the Baltic coast.[31] The interpreters at ACIU gained recognition for their expertise, F/O Constance Babington Smith, MBE and Sarah (Churchill) Oliver being among the noted names.[32] A scientific approach to reconnaissance developed, topped by the involvement of the Prime Minister when particularly notable results were discussed, such as the discovery of German jet fighters in test. The RAF also early developed the standard three-phase interpretation procedure: first phase required immediate response (such as advancing columns of armor sighted); second phase required 24- hour handling (such as concentrations of landing craft in ports); and third phase was for long-term analysis (such as industrial targets like coal gasification plants). Also, the distinction between strategic and tactical reconnaissance became clear, and sub-specialties like weather reconnaissance, radar photography, and bomb-damage assessment (BDA) became current. Both sides developed programs of regular weather reconnaissance in the Atlantic. In addition, the technique widely known as “dicing” – extreme low-altitude photography at high speed – came to be adopted by the Allies for special work.[33] Colonel Roosevelt pioneered night photography over Sicily. Flash bombs had to set off at very precise timing in order to capture the image, and in time the Edgerton D-2 Flash System came into wide use, this involving capacitor discharge at precise intervals.[34] Also, infrared film began to be used at the end of the war.[35] It was generally agreed that the Mosquito, designated F-8 by the Americans, was the best platform – apart from its performance, it offered the use of another operator in the glazed nose, which made both navigation and the very delicate selection of camera controls to match speed and altitude easier than in the single-seat F-5 Lightnings. Nonetheless, the Americans began to standardize on F-5s and F-6 Mustangs in order to promote an indigenous capability and break away from the RAF's tutelage.[36]

Endgame

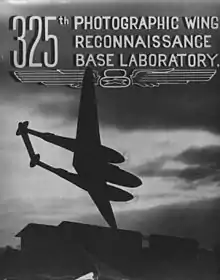

By the invasion of Normandy in June 1944, the U.S. 8th and 9th Air Forces had an immense reconnaissance wing in Colonel Roosevelt's 325th Reconnaissance Wing. It commanded two groups, the 25th Bombardment Group at RAF Watton and the 7th PRG at RAF Mount Farm (other units supported tactical reconnaissance for the 9th Air Force). The seven squadrons of the 325th provided routine weather recon, pathfinder-services, BDA, chaff and other electronic services, radar photography and night missions, as well as special operations in support of inserted agents. In Italy, the Mediterranean Allied Photographic Reconnaissance Wing under Colonel Polifka provided similar services, and using staging bases in the Ukraine these units together could provide full, regular coverage of the shrinking Axis territory.

The RAF maintained a similar large number of reconnaissance squadrons, dominated by Spitfires and Mosquitos; however, in the Far East and the Middle East, less capable types tended to be allocated to reconnaissance and army cooperation. For example, in Iraq during the 1941 Nazi coup, the RAF relied on Hawker Audax biplanes. What had begun with one PRU in 1940 eventually amounted to several dozen squadrons worldwide.

Because of a singular devotion to victory through strategic bombing, the USAAF placed extraordinary emphasis on reconnaissance. As an example, the need to destroy German petroleum, oil and lubricants facilities required careful monitoring to decide not only what to hit, but when and how much – and then when to hit them again. This led to an emphasis on long-term surveillance, and also to centralized analysis correlating photography with other sources (such as agents on the ground). Although the RAF usually preferred area bombing, it promoted a similar reconnaissance emphasis, for example in the celebrated discovery, coverage, and analysis of the Peenemunde rocket range which culminated in the Operation Hydra raid in August 1943. The Axis had no comparable strategic capability and most Axis air resources were consumed in support of massive ground battles.

In general, Western reconnaissance aircraft were unarmed, not only to maximize performance, but to emphasize the objective of bringing back pictures, not engaging the enemy. They also usually flew singly or in widely spread pairs. In special circumstances it was necessary to bring along fighter escorts; this phenomenon arose again in the last months when the hitherto sovereign Mosquito began to be picked off by Messerschmitt Me 262 jets. Selected heavy bombers carried film cameras and cameramen. The 8th Air Force's 8th Combat Camera Unit thus documented much of the air war, and these films are much more frequently shown today than are the static images of regular reconnaissance.

D-Day constituted the single biggest photo-reconnaissance job in history. One who was there reported that at the ACIU, 1,700 officers and enlistees studied 85,000 images daily. Two days before the Allied invasion date, an American pilot, Joe Thompson, flew a mission that included photographing a list of sites over France, one of which was called Grandcamp.[37] It was a German battery overlooking a sandy outcropping now known as Omaha Beach.[38]: 20 Thompson had, two months prior, done reconnaissance of the whole Normandy coast at an altitude of 50 feet and had no idea of the significance of this repeat flight obtaining verticals at 2500 ft.[39]: 236 When he landed after this mission on June 4, 1944, coming to a stop on the tarmac with his plane's propeller blades still turning, a young soldier in a jeep screeched his tires stopping by Thompson's plane to remove the film. He drove it to Eisenhower's headquarters at Wilton House in Salisbury, about 20 miles away.[38]: 20 In his later book, Crusade in Europe, Eisenhower said, "Airplane photography searched out even minute details...[and] information so derived was available to our troops within a matter of hours."[40]

There were 12,000 Allied aircraft in the air over the region On D–Day.[41] If the invasion was counted as a major reconnaissance success, the German Ardennes offensive (Battle of the Bulge) in December was a major failure. Post-battle investigation maintained that the problem lay not in obtaining airborne evidence, but in integrating the numerous disparate data points into a coherent picture. Also, by then the Germans had learned to move by night and under cover of seasonal bad weather when possible. These countermeasures, also including going underground and exploiting snow cover, came to represent some of the limitations of overhead reconnaissance even in conditions of overwhelming air superiority.[42]

German reconnaissance languished in the west because radar-aided air defenses there made survival unlikely. Apart from the ubiquitous Ju 88s, the Heinkel He 177s proved valuable as a reconnaissance platform but that type was extremely troubled mechanically. In effect, the Luftwaffe was unable to carry out regular surveillance of critical targets like the British Isles prior to the invasion of June 1944; indeed, one German aircraft was “allowed” to overfly Dover in order to report on a fake invasion build-up there.[43] (However, Brugioni maintains that Germany did conduct sufficient flights to estimate the time and place of the invasion.)[44]

After this, a few jets became available: Arado Ar 234 allocated to Sonderkommandos, but although they were uninterceptable the results brought back seems to have added little value to the German war effort. A version of the very advanced Dornier Do 335 Pfeil was assigned to reconnaissance duties. Reconnaissance was more successful in the East, and the Germans did carry out large-scale photographic mapping, some of which would later benefit the western Allies. The Luftwaffe also successfully deployed night photography with flash bombs, as amply documented by the BDA of the annihilating German attack on the USAAF in the Ukrainian SSR in June 1944.[45]

At sea, Germany had a considerable early lead in long-range aircraft, chiefly represented by the Fw 200 Condor. This was a converted airliner unsuitable for the rigors of combat. As a Fernaufklärer, the large Junkers Ju 290 had the necessary range, but it was produced in low numbers and was very vulnerable. Seeaufklärer and Kustenflieger groups used seaplanes of many different types with considerable success in coastal areas, especially from Norway. By 1942–43 the Condor menace was subsiding, and German long-range aircraft had great difficulty surviving in the Atlantic. They were much more effective in Northern Norway against the Arctic convoys. Germany adopted armed reconnaissance as an expediency at these long ranges.[46]

Finally, the industrial centers arrayed against the Axis – in the United States and the Urals and Siberia – were simply out of reach of strategic reconnaissance. As always it was at the tactical level that the Germans excelled, and short-range aircraft were able to hold their own in the East until fuel, pilots, and even aircraft became depleted. Experts generally hold that the top German leadership failed to understand airpower, and Hitler has been especially blamed for lacking the strategic perspective that the West Allies adopted.[47] But since the industrial mismatch was insurmountable, it is doubtful what difference a greater German emphasis on strategic reconnaissance and commensurate bombardment would have made.

The Allies were slow to allocate very long-ranged aircraft to maritime duties. They needed long-range maritime surveillance to hunt submarines just as the Luftwaffe needed it to hunt convoys. Stung by catastrophic losses, in April 1943 the United States finally allocated sufficient numbers of VLR (very long range) aircraft to suppress submarines. This was an important factor in defeating the U-boat offensive that spring. Maritime versions of the Consolidated B-24 Liberator served effectively in this maritime patrol role.[48]

The Soviet Union had virtually no in-depth reconnaissance capability and relied overwhelmingly on human intelligence. By the time of the brief U.S.-Soviet shuttle bombing program in the summer of 1944, the Americans noted that Soviet reconnaissance did not venture far past the front, and that photographic technology was far inferior. At Poltava, the U.S. reconnaissance detachment shared all imagery as well as tactics and technology with their Soviet counterparts, enabling the latter to comprehend American operations and develop an indigenous capability. Besides, for strategic intelligence the Soviets had thoroughly infiltrated both Allied and Axis governments at the most sensitive levels.[49]

In the Pacific, long range was at a premium, and both fleet and army aircraft soon reflected an overwhelming American advantage. The U.S. Navy, prompted by the intelligence failure at Pearl Harbor, invested in long-range patrol aircraft like the ubiquitous PBY Catalina. However, from early on the Allies had a tremendous unseen advantage in signals intelligence and cryptography, being able to read Axis codes. This led to economies in reconnaissance.

Surprising considering her small industrial base, Japan built very high-quality reconnaissance aircraft. These included several platforms such as the unarmed Mitsubishi Ki-46 "Dinah" known as the "Japanese Mosquito"(?); and the extreme-long-range Kawanishi H8K "Emily", widely considered the best flying boat of the war. These aircraft reached as far as Ceylon. The Navy's standard Nakajima C6N "Myrt" was also an extremely capable reconnaissance platform from 1944 on. But it does not appear that Japan had the overall industrial capability nor made the intellectual investment necessary to run a competitive reconnaissance branch. From 1943, the Japanese were virtually always on the defensive, while new long-range, high-altitude U.S. aircraft climaxing with the Boeing B-29 Superfortress (F-13 in the reconnaissance role) provided overwhelming American coverage of the Home Islands from mid-1944.

Cameras

Aircraft usually carried several different camera configurations in one bay. A common installation was the trimetrogon: one vertical, and one oblique to each side. Often one aircraft carried several different camera-lens configurations for special purposes. The British found that a rearwards-facing camera could overcome some of the jitter from sideways movement, and that very low-level photography (called dicing) benefitted from an almost side-ways camera view. Most surveillance was conducted from extremely high altitudes, requiring long-focus optics, as reflected in “Goddard's Law”: In photo-reconnaissance there is no substitute for focal length.[50]

In the United States, the primary aerial cameras were the K-series and naval F-series produced by Fairchild. Inventor Sherman Fairchild had developed the K-3 in 1919 based on experience from the Great War. His work would dominate the field for decades, including in the form of foreign copies. Initially many cameras still used German Zeiss and Schneider optics. The U.S. K-17 (9x9 inch image) with several different lenses was especially ubiquitous. For mapping, a six-inch lens was standard. The less common K-18 (9x18) was used for high altitude. K-19s were used at night, and the small K-20s (4x5) for low-level obliques. Although standardized on 9X9 inch plates, several similar camera types came into use. The period saw a rapid development of longer focal lengths in order to enable high-resolution high-altitude photography. 12, 24, 36 and ultimately 60-inch lenses came into use. The Americans also produced and used British cameras (F24 as K24). The old James Bagley T-1 mapping camera and its multi-lens descendants were still used strictly for aerial mapping. The Navy used variants of the Fairchild series.[51]

In Britain, the small F24 (5x5 image) and the derivative but much larger F52 (8.5x7) aerial cameras dominated, the former being used mostly for night photography with the aid of flash bombs. Up to 40-inch lenses were fitted. These cameras had shutter-in-focal-plane, whereas U.S. cameras standardized on shutter-between-lenses, claiming this reduced distortion.[52]

Exposures typically required the use of a cockpit-mounted intervalometer, set by reference to speed, altitude, and interval so that the pilot or observer could obtain the correct exposures by keying a switch. Great flight precision was needed especially for exposures for stereography and cartography in general.

While German optics were superior, experts noted that standard German reconnaissance cameras, though excellent, were heavy and not optimized for aerial use. Leica seemed to be the main camera manufacturer while optics production was concentrated at ISCO Göttingen (Schneider) and Zeiss. The bulky Rb30 (Reihenbild) and its variants were in common use. This required at least two men for handling and produced 12x12 (32 cm) images. It was supplemented by smaller hand-held cameras, Hk13 (Handkamera) and Hk19, which also could be fitted into the rear fuselage of single-engine fighters. In general, the focal length in cm was indicated by the first number and the plate size by the second, thus Rb50/30. As an example, the Do 17P carried Rb 20/30 + Rb 50/30 or Rb 20/18 + Rb 50/18 cameras as well as defensive guns. The cameras were controlled remotely by the crew from the cockpit. Other configurations arose as needed.[53]

Japanese cameras were a mixture of domestic and imported/copied types. The Navy often used copies of the American Fairchild K-8 and K-20, and also a copy of the U.S. Navy's F-8. The Army used small, usually handheld Type 96, 99 (K-20), and 100. Konica and Nikon were the main manufactures. Some German cameras were also used. As Japanese reconnaissance aircraft were multi-seat, the rear observer usually operated the cameras. Japan trained only a relative handful of officers as photo interpreters.[54]

![]() Media related to Aerial photography in World War II at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Aerial photography in World War II at Wikimedia Commons

Legacy

Because of their initial disregard for reconnaissance, all belligerents shared in the failure to develop and field a dedicated, survivable air reconnaissance platform, although they belatedly recognized the need therefore. As a result, nearly all recon aircraft were converted combat aircraft, and the proposed dedicated U.S. types (F-11 and F-12) were canceled after the peace. Soon after the war, the CIA did develop such a dedicated aircraft, the U-2. From 1945 aerial reconnaissance became a critical, high-priority component of national security in both the U.S. and Britain.

The results obtained from reconnaissance were controversial. Bomb Damage Assessment (BDA) generally revealed less damage than bombers estimated, and even the BDA was found to be inflated after ground truth could be established. The tendency to overestimate both threat and damage was endemic to the field.[55]

Questions arose over why German reconnaissance had been ineffective. Babington Smith noted that the Zossen image library was soon discovered in a barn in Bad Reichenhall near Berchtesgaden, and that the square-foot sized photographs were impressive. But interrogations revealed that the interpreters were poorly trained, did not use stereoscopes, and “it was a horrible warning as to what photographic intelligence can become if it is based on the wrong concepts, and staffed almost entirely by uninspired plodders.”[56]

The failure of the Axis to measure up in reconnaissance cannot be ascribed to technical deficiency or indifference. Despite many efforts in this direction, it also cannot be wholly ascribed to top-level stupidity, since the Axis had no monopoly on this either. As in many other aspects of the war, it instead highlighted that reconnaissance must be viewed and developed holistically, as a national (or multinational) capability integrating many advanced resources, scientific, industrial, and intellectual; it also requires a centralized management tying it in with other intelligence specialties and related disciplines like targeting. In these matters, once aroused, the Anglo powers together had the required heft and persistence; the opposition simply was not nearly as strong or as mentally adjusted to a protracted global conflict.[57]

One of the top objectives of Allied occupation was the center of optical excellence in Jena; Colonel Goddard said that U.S. bombers had orders to spare Jena. In June 1945 the Americans under Goddard evacuated most of the top scientific staff to the West; however, Soviet troops moved the physical plant to the USSR, enslaving the remaining high-value workers there.[58]

As soon as the war ended, the USAAF in Europe used existing resources in an all-out effort to map Europe from the air before diplomatic considerations would make it difficult. Similar efforts were made elsewhere. The United States got access to a limited amount of German coverage of the European part of the Soviet Union, and soon began a costly and technically ambitious program to obtain pictures of the rest.

From 1946, the focus was no longer just on photography, but on signals intelligence and especially on new air sampling methods to detect and analyze nuclear fall-out. The extremely close operating relationship between the RAF and the USAAF (USAF from 1947) would survive the war, and the tactics, technology, terminology and in general the shared intellectual infrastructure in aerial surveillance and analysis would transition into the Cold War, becoming embodied in the National Reconnaissance Office by 1960. By then, no other country, including the Soviet Union, had national technical means for reconnaissance remotely rivaling those the RAF-USAF founded during the war.[59]

See also

References

- ↑ Babington Smith, p78; Stanley, p268 et passim

- ↑ Goddard, 240

- ↑ Goddard, 127–131 e.a.

- ↑ Babington Smith, p6

- ↑ Kreis, 81, e.a.

- ↑ Leaf, pp14–38

- ↑ Goddard, p25

- ↑ Leaf, p18

- ↑ Ehlers

- ↑ Stanley, Staerck

- ↑ Ehlers

- ↑ Leaf, p48

- ↑ Goddard. See also Arnold, Henry: Global Mission. General Arnold was one of the fact-finders in Britain in spring 1941.

- ↑ St. Exupery: Flight to Arras, 1942.

- ↑ Recovery of the aerial photographs of Ethiopia in the 1930s

- ↑ IGM, L’Istituto Geografico Militare in Africa Orientale, 1885 - 1937, Istituto Geografico Militare, Roma, 1939

- ↑ Hooton

- ↑ Goddard, pp340-41

- ↑ Hooton, pp197–201

- ↑ Hooton, p199; Babington Smith

- ↑ Stanley

- ↑ Hooton

- ↑ Stanley

- ↑ Hansen, pp354–387

- ↑ numerous investigations of Pearl Harbor reached this conclusion, which is still preferred to alternative theories.

- ↑ Goddard, p297, 299

- ↑ Hansen, p275-7

- ↑ "P-38 F-5 Reconnaissance Mission to Rabaul" on YouTube

- ↑ Hansen

- ↑ Leaf

- ↑ Leaf, pp99–103

- ↑ Babington Smith

- ↑ Hansen, 280–281

- ↑ Goddard, 329–330

- ↑ Goddard, 236

- ↑ Keen, Kreis

- ↑ Rogers, David P. (April 1, 1997). "The Camera Was Their Weapon". Army Magazine. Association of the U.S. Army. 47:4: 50–54.

- 1 2 Thompson, Joseph; Delveaux, Tom (2006). Tiger Joe: A photographic Diary of a World War II Aerial Reconnaissance Pilot. Nashville, Tennessee: Eveready Press. ISBN 0975871471.

- ↑ Missions Remembered: Recollections of the World War II Air War. New York: McGraw–Hill. 1998. ISBN 0070016496.

- ↑ Eisenhower, Dwight D. (2021). Crusade in Europe : A Personal Account of World War II (First Vintage Books December 2021 ed.). New York: Knopf Doubleday. p. 541. ISBN 9780593314852.

- ↑ Brugioni, 23–26

- ↑ Babington Smith, 255–257

- ↑ Goddard, 331

- ↑ Brugioni

- ↑ Hansen, 372–375

- ↑ Hooton

- ↑ Hooton

- ↑ The USAAF in World War II (official history)

- ↑ Hansen, 366–370; Stanley, 186

- ↑ Goddard; Stanley

- ↑ Stanley

- ↑ Staerck, 12–14

- ↑ Stanley, 172–176 e.a.

- ↑ Stanley

- ↑ Ehlers

- ↑ Bab. Smith, 257-9

- ↑ Ehlers

- ↑ Goddard, 345

- ↑ Brugioni

Bibliography

- Babington Smith, Constance. Evidence in Camera / Air Spy. 1957 / 1985.

- Brugioni, Dino. Eyes in the Sky: Eisenhower, the CIA, and Cold War Aerial Espionage.

- Ehlers, Robert S: "Bomb Damage Assessment". Dissertation, OSU, 2005.

- Fussell Kean, Patricia. Eyes of the Eighth. CAVU, Sun City, 1996.

- Goddard, George: Overview. Doubleday, New York, 1969.

- Hansen, Chris. Enfant Terrible: The Times and Schemes of General Elliott Roosevelt. Able Baker Press, Tucson, 2012

- Hooton, E.R.: Phoenix Triumphant. Brockhampton, 1999.

- Kreis, John F. (ed.): Piercing the Fog. Air Force History and Museums Program, Bolling AFB, 1996.

- Leaf, Edward: Above all, Unseen. RAF PRUs 1939–45. Haynes Publ. Yeovil, 1997.

- Staerck, Chris (ed.): Allied Photo Reconnaissance of WWII. PRC, London, 1998.

- Stanley, Roy. World War II Photo reconnaissance. Scribner, 1981.