Within the sociology of knowledge, agnotology (formerly agnatology) is the study of deliberate, culturally induced ignorance or doubt, typically to sell a product, influence opinion, or win favour, particularly through the publication of inaccurate or misleading scientific data (disinformation).[5][6] More generally, the term includes the condition where more knowledge of a subject creates greater uncertainty.

Stanford University professor Robert N. Proctor cites the tobacco industry's public relations campaign to manufacture doubt about the adverse health effects of tobacco use as a prime example.[7][8] David Dunning of Cornell University warns that powerful interests exploit the internet to "propagate ignorance".[6]

Agents of culturally induced ignorance include the media, corporations, and government agencies, through secrecy and suppression of information, document destruction, and selective memory.[9] Passive causes include structural information bubbles, including those that reflect racial and class differences, based on access to information.

Agnotology also focuses on how and why diverse knowledge does not "come to be", or is ignored or delayed. For example, knowledge about plate tectonics was censored and delayed for at least a decade because some evidence remained classified military information related to undersea warfare.[7]

The availability of large amounts of knowledge may allow people to cherry-pick information (whether or not factual) that reinforces their beliefs[10] and ignore inconvenient knowledge by consuming repetitive or fact-free entertainment. Evidence conflicts on how television affects viewers.[11]

Origins

There is a cult of ignorance in the United States, and there has always been. The strain of anti-intellectualism has been a constant thread winding its way through our political and cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means that

"my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge".

Isaac Asimov, 1980[12]

The term was coined in 1992 by linguist and social historian Iain Boal[13][5][14][15] at the request of Stanford University professor Robert N. Proctor.[16] The word is based on the Neoclassical Greek word agnōsis (ἄγνωσις, 'not knowing'; cf. Attic Greek ἄγνωτος, 'unknown' and -logia (-λογία).[7]

The term "agnotology" first appeared in print in a footnote in Stanford University professor Proctor's 1995 book, The Cancer Wars: How Politics Shapes What We Know and Don't Know About Cancer:

Historians and philosophers of science have tended to treat ignorance as an ever-expanding vacuum into which knowledge is sucked – or even, as Johannes Kepler once put it, as the mother who must die for science to be born. Ignorance, though, is more complex than this. It has a distinct and changing political geography that is often an excellent indicator of the politics of knowledge. We need a political agnotology to complement our political epistemologies.[17]

In a 2001 interview about his lapidary work with agate, Proctor used the term to describe his research "only half jokingly" as "agnotology". He connected the topics by noting the lack of geologic knowledge and study of agate since its first known description by Theophrastus in 300 BC, relative to the extensive research on other rocks and minerals such as diamonds, asbestos, granite, and coal. He said agate was a "victim of scientific disinterest," the same "structured apathy" he called "the social construction of ignorance".[18]

He was later quoted as calling it "agnotology, the study of ignorance," in a 2003 The New York Times story on medical historians who testify as expert witnesses.[19]

In 2004, Schiebinger[20] claimed that agnotology questions why humans do not know important information and that it could be an "outcome of cultural and political struggle".[21]

In 2004, Schiebinger offered a more precise definition in a paper on 18th-century voyages of scientific discovery and gender relations,[20] and contrasted it with epistemology, the theory of knowledge, saying that the latter questions how humans know while the former questions why humans do not know: "Ignorance is often not merely the absence of knowledge but an outcome of cultural and political struggle."[21]

Proctor co-organized events with Londa Schiebinger, his wife and fellow professor of science history.[22][9] In 2008, they published an anthology entitled Agnotology: The Making and Unmaking of Ignorance, which "provides a new theoretical perspective to broaden traditional questions about 'how we know' to ask: Why don't we know what we don't know?" They locate agnotology within the field of epistemology.[23]

Examples

The fossil fuel industry used the technique in its campaign against the scientific consensus on climate change. It became the focus of the 2010 book Merchants of Doubt by Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway.[24] Oil companies paid teams of scientists to downplay its effects.[25]

Michael Betancourt used agnotology in a critical assessment of political economy in a 2010 article and book.[26][27] His analysis focused on the housing bubble as well as the 1980 to 2008 period. Betancourt argued that this political economy should be termed "agnotologic capitalism", claiming that the systematic production and maintenance of ignorance enabled a "bubble economy" that allowed the economy to function.[20] In his view, the role of affective labor is to create/maintain agnotologic views that enable the maintenance of the capitalist status quo. This is done by proffering counters to every fact, creating contention and confusion that is difficult to resolve. This confusion reduces dissent by deenergizing its motivating alienation and thus its potential to address weaknesses that may trigger collapse.[26]

Related concepts

Agnoiology

From the same Greek roots, agnoiology refers either to "the science or study of ignorance, which determines its quality and conditions"[28] or "the doctrine concerning those things of which we are necessarily ignorant,"[29] describing a branch of philosophy studied by James Frederick Ferrier in the 19th century.[30]

Ainigmology

Anthropologist Glenn Stone points out that some examples of agnotology (such as work promoting tobacco use) do not actually create a lack of knowledge so much as they create confusion. As a more accurate term Stone suggested "ainigmology", from the Greek root ainigma (as in 'enigma'), referring to riddles or to language that obscures the true meaning of a story.[31]

Cognitronics

An emerging scientific discipline that connects to agnotology is cognitronics,[32][33] which aims to explain distortions in perception caused by the information society and globalization and cope with these distortions.[33]

Unknowledge

Irvin C. Schick distinguishes unknowledge from ignorance, using the example of "terra incognita" in early maps in which mapmakers marked unexplored territories with that or similar labels, which provided "potential objects of Western political and economic attention."[34]

See also

- Antiscience – Attitudes that reject science and the scientific method

- Anti-intellectualism – Hostility to and mistrust of education, philosophy, art, literature, and science

- Cancer Wars – Documentary, a six-part documentary that aired on PBS in 1997, based on Robert N. Proctor's 1995 book, Cancer Wars: How Politics Shapes What we Know and Don't Know About Cancer

- Cognitive dissonance – Stress from contradictory beliefs, a social psychology theory that may explain the ease of maintaining ignorance (because people are driven to ignore conflicting evidence) and which also provides clues to how to bring about knowledge (perhaps by forcing the learner to reconcile reality with long-held, though inaccurate beliefs; see Socratic method)

- Cognitive inertia – Lack of motivation to mentally tackle a problem or issue

- Confirmation bias – Bias confirming existing attitudes

- Creationism – Belief that nature originated through supernatural acts, systematic denial of scientific biological realities by misrepresenting them in terms of various dogmatic tenets

- Denialism – Person's choice to deny psychologically uncomfortable truth

- Doubt Is Their Product – 2008 book by David Michaels

- The Dunning–Kruger effect, a cognitive bias whereby people with low ability at a task overestimate their skill level, and people with high ability at a task underestimate their skill level.

- Fear, uncertainty and doubt (FUD) – Tactic used to influence opinion, a disinformation technique using the appeal to fear

- Intelligent design – Pseudoscientific argument for the existence of God, a class of creationism that attempts to support assorted topics in biological denialism by misrepresenting them and related junk science as scientific research

- Japanese commercial whaling – Commercial hunting of whales by the Japanese fishing industry, an attempt at obfuscation of the culpability of commercial whaling by misrepresenting its junk-scientific rationale as scientific research.

- Junk science – Scientific data considered to be spurious

- Merchants of Doubt – 2010 book by Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway

- Misinformation

- Historical negationism – Illegitimate distortion of the historical record

- Neo-Luddism – Philosophy opposing modern technology

- Obscurantism – Practice of obscuring information

- Sociology of scientific ignorance – Study of ignorance in science, or Ignorance Studies, the study of ignorance as something relevant.

- Subvertising – Parody advertising

- The Republican War on Science – 2005 book by Chris Mooney

- Vaccine controversies – Reluctance or refusal to be vaccinated or have one's children vaccinated, based on assorted junk-scientific strategies to misrepresent life- and health-saving technologies as harmful rather than beneficial.

References

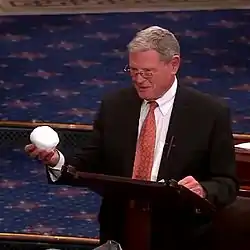

- ↑ Barrett, Ted (27 February 2015). "Inhofe brings snowball on Senate floor as evidence globe is not warming". CNN. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023.

- ↑ Cama, Timothy (26 February 2015). "Inhofe hurls snowball on Senate floor". The Hill. Archived from the original on 14 October 2022.

- ↑ Woolf, Nicky (26 February 2015). "Republican Senate environment chief uses snowball as prop in climate rant". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 October 2023.

- ↑ "NASA, NOAA Analyses Reveal Record-Shattering Global Warm Temperatures in 2015". NASA. 20 January 2016. Archived from the original on 29 December 2023.

- 1 2 Kreye, Andrian (2007). "We Will Overcome Agnotology (The Cultural Production Of Ignorance)". The Edge World Question Center 2007. Edge Foundation. p. 6. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

This is about a society's choice between listening to science and falling prey to what Stanford science historian Robert N. Proctor calls agnotology (the cultural production of ignorance)

- 1 2 Kenyon, Georgina (6 January 2016). "The man who studies the spread of ignorance". BBC Future.

- 1 2 3 Palmer, Barbara (4 October 2005). "Conference to explore the social construction of ignorance". Stanford News Service. Archived from the original on 24 July 2007. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

Proctor uses the term "agnotology" – a word coined from agnosis, meaning "not knowing" – to describe a new approach to looking at knowledge through the study of ignorance.

- ↑ Kreye, Andrian (17 May 2010). "Polonium in Zigaretten : Müll in der Kippe (Polonium in cigarettes : Garbage in the butt)". Sueddeutsche Zeitung. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

Proctor:...Die Tabakindustrie hat ... verlangt, dass mehr geforscht wird. Das ist reine Ablenkungsforschung. Wir untersuchen in Stanford inzwischen, wie Unwissen hergestellt wird. Es ist eine Kunst – wir nennen sie Agnotologie. (Proctor:...The tobacco industry has ... called for further study. That is pure distraction research. At Stanford, we study how ignorance is manufactured. It is an art we call agnotology.)

- 1 2 "Agnotology: The Cultural Production of Ignorance". Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- ↑ Knobloch-Westerwick (2009). "Study: Americans choose media messages that agree with their views". Communication Research. Sage. 36: 426–448. doi:10.1177/0093650209333030. S2CID 26354296. Archived from the original on 9 July 2009. Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- ↑ Thakkar RR, Garrison MM, Christakis DA (5 November 2006). "A Systematic Review for the Effects of Television Viewing by Infants and Preschoolers". Pediatrics. 118 (5): 2025–2031. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-1307. PMID 17079575. S2CID 26071118.

- ↑ Pyle, George (6 April 2020). "George Pyle: It can be hard to know whom to trust. And easy to know whom not to". The Salt Lake Tribune. Archived from the original on 13 April 2020.

- ↑ "My hope for devising a new term was to suggest the opposite, namely, the historicity and artifactuality of non-knowing and the non-known-and the potential fruitfulness of studying such things. In 1992, I posed this challenge to the linguist Iain Boal, and it was he who came up with the term agnotology, in the spring of that year.” Robert N. Proctor, "Postscript on the Coining of the Term 'Agnotology'", in "Agnotology: The Making and Unmaking of Ignorance", Eds. Robert N. Proctor and Londa Schiebinger, 2008, Stanford University Press, page 27.

- ↑ Agnotology: understanding our ignorance, 15 December 2016, retrieved 31 January 2017 interview with Robert Proctor "So I asked a linguist colleague of mine, Iain Boal, if he could coin a term that would designate the production of ignorance and the study of ignorance, and we came up with a number of different possibilities."

- ↑ Arenson, Karen W. (22 August 2006). "What Organizations Don't Want to Know Can Hurt". The New York Times.

'there is a lot more protectiveness than there used to be,' said Dr. Proctor, who is shaping a new field, the study of ignorance, which he calls agnotology. 'It is often safer not to know.'

- ↑ "Stanford History Department : Robert N. Proctor". Stanford University. Archived from the original on 19 March 2007. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- ↑ Proctor 1995, p. 8.

- ↑ Brown, Nancy Marie (September 2001). "The Agateer". Research Penn State. Archived from the original on 11 August 2007. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- ↑ Cohen, Patricia (14 June 2003). "History for Hire in Industry Lawsuits". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

Mr. Proctor, who describes his specialty as "agnotology, the study of ignorance", argues that the tobacco industry has tried to give the impression that the hazards of cigarette smoking are still an open question even when the scientific evidence is indisputable. "The tobacco industry is famous for having seen itself as a manufacturer of two different products," he said, "tobacco and doubt".

- 1 2 3 "IRWG director hopes to create 'go to' center for gender studies". Stanford News Service. 13 October 2004. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- 1 2 Schiebinger, L. (2004). "Feminist History of Colonial Science". Hypatia. 19 (1): 233–254. doi:10.2979/HYP.2004.19.1.233.

I develop a methodological tool that historian of science Robert Proctor has called "agnotology"—the study of culturally-induced ignorances—that serves as a counterweight to more traditional concerns for epistemology, refocusing questions about "how we know" to include questions about what we do not know, and why not. Ignorance is often not merely the absence of knowledge but an outcome of the cultural and political struggle.

- ↑ "Agnatology: The Cultural Production of Ignorance". The British Society for the History of Science. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

Science, Medicine, and Technology in Culture Pennsylvania University Presents a Workshop: ... Robert N. Proctor and Londa Schiebinger, co-organizers

- ↑ Proctor & Schiebinger 2008.

- ↑ Oreskes, Naomi; Conway, Erik M. (2010). Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming. Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1608193943.

- ↑ Herwig, A.; Simoncini, M. (2016). Law and the Management of Disasters: The Challenge of Resilience. Law, Science and Society. Taylor & Francis. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-317-27368-4. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- 1 2 Betancourt, Michael (2010). Kroker, Arthur; Kroker, Marilouise (eds.). "Immaterial Value and Scarcity in Digital Capitalism". CTheory, Theory Beyond the Codes: tbc002. Archived from the original on 5 October 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- ↑ Betancourt, Michael (2015). The critique of digital capitalism : an analysis of the political economy of digital culture and technology. New York: Punctum Books. ISBN 978-0-692-59844-3. OCLC 1097118186.

- ↑ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 378.

- ↑ Porter, Noah, ed. (1913). Webster's Revised Unabridged Dictionary. G & C. Merriam Co.

- ↑ "James Frederick Ferrier". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- ↑ Stone, Glenn Davis (2014). "Biosecurity in the Age of Genetic Engineering". In Chen, Nancy; Sharp, Lesley A. (eds.). Bioinsecurity and vulnerability (1 ed.). Santa Fe, New Mexico: School for Advanced Research Press. pp. 71–86. ISBN 978-1-938645-42-6. OCLC 881518431.

- ↑ Rueckert, Ulrich (2020). "Human-Machine Interaction and Cognitronics". In Murmann, B.; Hoefflinger, B. (eds.). NANO-CHIPS 2030. The Frontiers Collection. Springer. pp. 549–562. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-18338-7_28. ISBN 978-3-030-18338-7. S2CID 226744728.

- 1 2 "THIRD INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE on COGNITONICS: The Science about the Human Being in the Digital World". Archived from the original on 29 November 2012. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ↑ Schick, İrvin Cemil (1999). The erotic margin : sexuality and spatiality in alteritist discourse. London: Verso. ISBN 1-85984-732-3. OCLC 40776818.

Further reading

- Angulo, A. J. (2016). Miseducation: A History of Ignorance-Making in America and Abroad. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-1932-9.

- Kenyon, Georgina (2016 January 6). "The man who studies the spread of ignorance." BBC Future.

- Michaels, David (2008). Doubt is Their Product: How industry's assault on science threatens your health. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530067-3.

- Mooney, Chris (2005). The Republican War on Science. Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-04676-2.

- Proctor, Robert N. (1995). Cancer Wars: How politics shapes what we know and don't know about cancer. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00859-9.

- Proctor, Robert N.; Schiebinger, Londa, eds. (2008). Agnotology: The Making and Unmaking of Ignorance (PDF). Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-5901-4. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- Smithson, Michael (1985). "Toward a social theory of ignorance". Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour. 20 (4): 323–346. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5914.1985.tb00049.x.