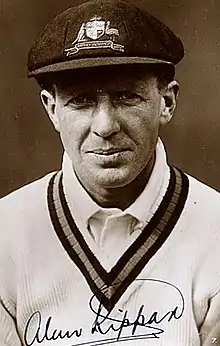

Kippax in 1930 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Alan Falconer Kippax | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 25 May 1897 Paddington, New South Wales, Australia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 5 September 1972 (aged 75) Bellevue Hill, New South Wales, Australia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nickname | Kip | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Batting | Right-handed | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bowling | Right-arm wrist spin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Role | Middle-order batsman | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| International information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| National side | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

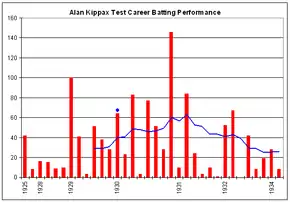

| Test debut (cap 122) | 27 February 1925 v England | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last Test | 22 August 1934 v England | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Domestic team information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years | Team | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1918/19–1935/36 | New South Wales | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Career statistics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Source: CricInfo, 8 January 2008 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Alan Falconer Kippax (25 May 1897 – 5 September 1972) was a cricketer for New South Wales (NSW) and Australia. Regarded as one of the great stylists of Australian cricket during the era between the two World Wars, Kippax overcame a late start to Test cricket to become a regular in the Australian team between the 1928–29 and 1932–33 seasons. A middle-order batsman, he toured England twice, and at domestic level was a prolific scorer and a highly considered leader of NSW for eight years. To an extent, his Test figures did not correspond with his great success for NSW and he is best remembered for a performance in domestic cricket—a world record last wicket partnership, set during a Sheffield Shield match in 1928–29. His career was curtailed by the controversial Bodyline tactics employed by England on their 1932–33 tour of Australia; Kippax wrote a book denouncing the tactics after the series concluded.

Kippax was an "impeccably correct and elegant batsman, [with] an upright, easy stance at the wicket; like his schoolboy idol Victor Trumper, he rolled his sleeves between wrist and elbow and excelled with the late cut",[1] who was probably at his peak during the 1920s.[2] His omission from the 1926 team to tour England caused great controversy at the time—especially as he hit a brilliant 271 not out against Victoria on the eve of selection. Kippax was well into his thirties by the time he became a consistent selection for the Test team. Highly regarded by both fellow players and spectators, Kippax's innings of 83 in the Lord's Test of 1930 induced Neville Cardus to comment that, "he pleased the eye of the connoisseur all the time."[3]

Early years

The third son of Arthur Percival Howell Kippax and his wife Sophie Estelle (née Craigie), Alan Kippax was born in the inner-city Sydney suburb of Paddington.[1] He attended both Bondi and Cleveland Street Public schools. At 14, Kippax joined Waverley (now Eastern Suburbs Cricket Club) and was a regular in the first-grade team within three years.[4] At this stage, first-class cricket was suspended because of World War I, but when competition resumed in the 1918–19 season he made his debut for New South Wales (NSW). However, the state possessed much batting talent, which was supplemented by the return to Australia of the Australian Imperial Forces cricket team that played in England after the armistice.[1] Therefore, Kippax's opportunities were restricted for a number of seasons. He also played a lot of baseball with the Waverley Baseball Club (usually at third base) and represented Australia against touring teams from American universities.[3]

Kippax's cricketing potential did not go completely unnoticed. He was offered a tour of New Zealand in the autumn of 1921. Playing in an Australian second team captained by the Test batsman Vernon Ransford, he made only two half-centuries in nine innings.[5] In the 1922–23 season, Kippax became a regular for NSW, scoring 631 runs at 90.14.[6] and led the side's first-class averages. The next season, he hit 248 in only 316 minutes against South Australia at the Sydney Cricket Ground (SCG), then toured New Zealand with the NSW team skippered by Charlie Macartney. Kippax made two centuries in his 461 runs (average 92.2) on the tour.[7]

He quickly won the respect of his fellow players and the spectators for his approach to the game. Alan McGilvray describes Kippax's demeanour and presence on the field:

... meticulous in his dress and his life, a man with a squeaky-clean image who would never raise his voice or allow his emotions to run away with him ... His shirt would always be buttoned the same way, the crease would always be sharp in his trousers, no hair would ever be out of place. He was an admirable engaging man.[8]

Journalists employed many superlatives to describe the Kippax style. Ray Robinson thought that Kippax's batting "had a silky quality not seen in any other player of his time or since"; he captivated the crowds with his late cut when he, "made a lissom bow over the ball and stroked it away with the bat's face downward, as if to squeeze the ball into the ground". His favourite hook shot propelled the ball "with such unhurried ease that the punishing power of the stroke was revealed only in the way the ball smacked against the fence." Donald Bradman believed him to be the best exponent of the hook shot in the game.[9]

International career

Kippax began the 1924–25 summer with 115 for NSW against an Australian XI at the SCG. In the Sheffield Shield he had scores of 127, 122 and 31, 212 not out and 40,[10] earning him a first Australian cap (at the age of 27) in the final Test of the Ashes series against England at Sydney. Sharing a 105 run partnership with Bill Ponsford in the first innings, Kippax impressed with a score of 42 from number seven.[11] Wisden commented that the partnership "turned the fortunes of the game",[12] and Australia went on to victory.[13]

Shock omission

Another 585 runs at 83.57 in the 1925–26 season looked likely to win Kippax a place in the team to tour England in 1926. He failed in the Test-trial match staged in early December, but made the highest score of the Sheffield Shield competition, 271 not out (in 423 minutes)[14] against Victoria at the SCG, which effectively steered NSW to the title. The subsequent omission of Kippax from the touring team is a famous blunder in Australian cricket history.[1] Although Kippax was nearly 29, former Australian captain Monty Noble called the non-selection a "crime against the cricketing youth of Australia".[15] His omission is usually attributed to "interstate parochialism" and was a "triumph of dullness over batting artistry."[3] Australia surrendered the Ashes on the tour, with much of the blame for the loss directed at the team's skipper, Herbie Collins. After he returned to Australia, administrators relieved Collins of the captaincy of his grade team and NSW,[16] thus creating an opportunity for Kippax.

Captain of NSW

Installed as leader of NSW, Kippax earned a reputation as one of Australia's leading batsmen over the next three years. His captaincy "welded with wit, kindness and some practical joking a raw team into a formidable unit, nurturing such youngsters as Archie Jackson, Stan McCabe and (Sir) Donald Bradman".[1] He hit a century in each innings against Queensland in their inaugural Sheffield Shield match in 1926–27. The following season he registered the highest score of his career, 315 not out in 388 minutes versus Queensland at the SCG.[3] Bradman wrote of this performance, "... although they say Victor Trumper was even more beautiful to watch, it is hard to conceive more graceful batting than our skipper produced on that occasion."[17] Kippax ended the season with 926 runs at an average of 84.18.[18]

The Test selectors still had Kippax under consideration and during March 1928, he again toured New Zealand with an Australian second team, but failed to pass 40 in the seven innings he played.[19] Restored to the Test team for the beginning of the 1928–29 Ashes series, Kippax made just 50 runs in four innings. Australia slipped to two heavy defeats and Kippax's place was not in jeopardy.

During the second Test at Sydney, Kippax was the central figure in the most controversial incident of the summer. Early in Australia's first innings, Kippax had nine runs on the board, when:

According to George Hele, the umpire at the bowler (Geary's) end, the latter delivered an undeviating ball just wide of Kippax’s legs. When the bails were seen to fall Hele refused an appeal for 'bowled'. [English fieldsman Jack] Hobbs, who had been at cover point, then appealed to Umpire Elder. Kippax at no time had left his crease. [Wicketkeeper] Duckworth had stepped to the leg side of the stumps to intercept the ball. The consensus of opinion is that it rebounded from one of his pads onto the wicket. Elder gave Kippax out 'bowled', something he had no right to do from square-leg. Kippax stood his ground for a time, disclosing later he left the wicket only because the persistent Hobbs had kept demanding, 'What sort of a sport are you to be standing here when you’re out?’ Vic Richardson tried to persuade his captain, Jack Ryder, to intercept Kippax before he crossed the incoming batsman and send him back. Ryder deliberated and dallied till it was too late. Elder afterwards admitted his mistake to Hele. 'What have I done?’ he asked.

— RS Whitington[20]

At the conclusion of the Test, Kippax travelled to Melbourne where he led NSW in a Sheffield Shield match beginning on 22 December. At stumps on the second day, NSW was staring at defeat as they were seven for 58 in pursuit of Victoria's first innings of 376. When play resumed on Christmas Day, NSW slipped to nine for 113, with Kippax 20 not out. However, the number eleven batsman Hal Hooker stuck with his captain as the score gradually mounted and the opposition's frustrations grew.

As news of the last-wicket stand spread, the crowd swelled, eventually reaching almost 15,000. Kippax's initial nervousness about his partner had disappeared, and most overs followed the same pattern - Kippax would crack as many as he could from the first two or three balls, and then happily take a single to leave Hooker to fend off the remaining four or five deliveries and paced his innings to perfection.

— Martin Williamson[21]

By the end of play, Kippax was well beyond his double century. The following day, when the stand was finally broken after 307 runs had been added in 304 minutes, Kippax stood on 260 not out. This "most remarkable of all world batting records,"[22] still stands today as the highest last-wicket partnership in first-class cricket.[23]

Retaining his place for the third Test that started just days later on the same ground, Kippax maintained his superb form and hit his maiden Test century in Australia's first innings. With Australia struggling against the pace of England's Harold Larwood,[24] Kippax steadied the innings and then launched an assault on Larwood, hooking him for four boundaries. Journalist Ray Robinson pointed out that before Kippax's flurry of fours, Larwood had taken 14 wickets at 18.3 runs in the series. After, he managed only four wickets for 472 runs.[22] Kippax followed up with 41 in the second innings, as Australia fell to their third consecutive defeat in the rubber and lost the Ashes.

Kippax completed the series with scores of 3 and 51 at Adelaide, and 38 and 28 in Australia's only winning effort, at the MCG. He received criticism in that, "his play was too delicately tuned for the hard business of winning matches."[25] Nevertheless, Kippax had another outstanding domestic season in 1929–30, hitting four centuries in his 744 runs, at an average of 62.[26] This time, he was one of the first picked to go to England.

Test regular

The 1930 tour of England was dominated by the emergence of Don Bradman. Kippax finished second to Bradman in the first-class averages and aggregates, scoring 1451 runs at 58.04.[27] He hit a century in each innings of the match with Sussex.[28] In the Tests, Kippax passed fifty four times in seven innings, without going on to a hundred. He shared two big partnerships with Bradman: 192 in the second Test at Lord's and 229 in the third Test at Leeds. However, Wisden rated his 64 not out on a wet wicket in the first Test at Nottingham as his best effort and summarised his tour thus:

Essentially a stylist, Kippax was in every sense a great batsman, for he could suit his game to the needs of the occasion. A beautiful driver to the off, he cut at times in delightful fashion, the slower wickets of England affecting his abilities in that direction in only the slightest degree.[29]

In the 1930–31 home series against the West Indies, Kippax began with what was to be his highest score in Test cricket (146 in under four hours) in the first Test at the Adelaide Oval. This was the first Test century in matches between the two teams. He made 84 in the third Test at Brisbane, sharing a partnership of 193 with Bradman. However, Wisden called Kippax's knock "unsteady"[30] and he failed in his remaining three Test innings. For NSW, he hit two centuries in the Sheffield Shield.[31]

The next season began badly for Kippax. Playing in a minor match at Parkes (in rural NSW) on a matting wicket, he had his nose broken by a delivery that bounced erratically – it hit a peg accidentally left under the mat when it was laid out.[32] On 6 November 1931, during NSW's first match of the season at Brisbane, he was struck a severe blow to the temple by a rising ball from fast bowler Pud Thurlow.[33] Taken to hospital, he retired from the match, but was selected for the first Test against South Africa, but scored only one run. He missed the second Test through injury, while his replacement Keith Rigg scored an impressive century on debut.[34]

Kippax came back for the third Test at Melbourne and rewarded the faith of the selectors by scoring 52 and 67, his two highest first-class innings of the season.[35] However, his best knock of the summer came on another rain-affected pitch at Melbourne in the final Test. He batted "serenely" to top score with an elegant 42.[3] The entire South Africa team only managed 36 and 45 in their two completed innings on a "treacherous" wicket.[36] As compensation for his lack of runs, Kippax led NSW to victory over Victoria in late January, which clinched the Sheffield Shield title for the state. During the winter of 1932, Kippax joined a private team that toured Canada and the USA, a tour organised by ex-Test bowler Arthur Mailey. Teammates noticed that his confidence was shaken by the blows to the head, and he no longer employed his famous hook shot.[32]

Bodyline series

England toured during the 1932–33 season, and played the infamous "Bodyline" series. While the tactic of using short-pitched bowling and close-in fielders on the leg side was originally conceived to stop Don Bradman's phenomenal run-making,[37] Bodyline was used against all the Australian batsmen. Kippax and the other Australian batsmen were adept at playing long innings and supporting Bradman in big partnerships—in Tests, Kippax had, in the past, featured in three stands of over 100 with Bradman—so the English were looking to undermine his confidence as well.[3]

Kippax secured his Test place with 179 against Queensland at the Gabba in mid-November 1932. A fortnight later, he led NSW against the tourists and failed in both innings as his side suffered a heavy defeat.[38] Selected for the first Test at Sydney, Kippax looked very uncomfortable in losing his wicket twice to the spearhead of the Bodyline attack, Harold Larwood. After batting at number four in the first innings, Kippax was demoted to bat behind his NSW understudy Stan McCabe in the second innings;[39] McCabe had scored a brilliant 187 not out in the first innings, defying Bodyline with aggressive hook shots. Irrespective of the change, Australia collapsed for 164, leaving England needing just one run for victory in their second innings.[40] In the dressing room, Kippax commented of Larwood, "he's too bloody fast for me".[33]

Omitted from the remainder of the series, Kippax became the first of several Australian batting "casualties" during the summer. While most sympathised with his misfortune, and attributed his lack of confidence to the blows he received the previous season,[41] Larwood was more succinct: "Kippax was scared stiff and he let you see it".[42] Employed as a radio commentator, Kippax spent the remainder of the series covering the Tests, and he also delivered a ten-minute round up of each day's play for the BBC, broadcast in England through its Empire short wave service.[43]

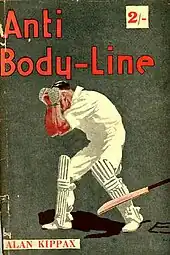

Outspoken in his criticism of Bodyline, Kippax combined with the cricketer and physician Eric Barbour to write the book Anti Body-Line, released just months after the tour ended. A short, polemical work aimed at an English readership, the book warned of the danger to the game if Bodyline was allowed as a legitimate tactic. Although the book kept the controversy raging, it was "calmly expressed' and "reasonable".[44]

After several seasons of struggling for runs, Kippax returned to form in 1933–34. Against Queensland at New Year, he hit 125 and shared a stand of 363 in only 135 minutes with Bradman. Altogether, he made four centuries and averaged almost 72 to earn selection for the 1934 tour of England.[45] Passed over for the vice-captaincy of the team in favour of Bradman, Kippax had the confidence of knowing that the Australian Board of Control had reached an agreement with the MCC that the Australians would not have to face Bodyline during the tour.[46]

Final tour

Beginning the tour with a duck, Kippax recovered with 89 at Leicester before contracting a heavy dose of influenza that forced him to miss the next four matches.[47] On his return, he struggled for form, and was not chosen for the first Test. Kippax was the third selector on tour, and was out-voted by his fellow selectors, so the press speculated that the decision caused disharmony within the team.[48] Australia won the game and Kippax failed in the next two tour matches, so he missed out on the next Test at Lord's, which was lost.

Struck down by serious illness again, Kippax was hospitalised with a (wrongly) suspected case of diphtheria and forced to miss the drawn Tests at Old Trafford and Leeds.[47] Eventually, he returned to play in late July and hit form at the right time. With the series locked at one-all, and a timeless Test to be played at The Oval to decide the Ashes, Australia needed to strengthen the batting. The experienced Kippax replaced the struggling youngster Len Darling in the middle order, for what proved to be his last Test.

The way the game unfolded, Kippax had little responsibility with the bat. A record partnership of 451 between Bill Ponsford and Don Bradman meant that Australia was four for 574 by the time he got to the crease. Kippax made 28 in just under an hour as Australia amassed 701 runs. He scored just 8 in the second innings, but Australia were victorious by 562 runs and regained the Ashes. Six days later, Kippax celebrated by making 250 against the Sussex bowling attack, his highest score in England and his first double century for more than five years. This boosted his first-class above 50 on what had been a tour of mixed fortunes.

Legacy

On the team's return from England, Kippax handed the NSW captaincy to Test teammate Bert Oldfield, and ended his first-class career with four Sheffield Shield matches for the state. His last century came in mid-December 1934, when he scored 139 against South Australia at the Adelaide Oval. This gave Kippax a total of 32 centuries for NSW, a record tally, subsequently beaten only by Michael Bevan.[49] His 6,096 runs (at 70.06) for NSW in Sheffield Shield matches contributed to five title-winning campaigns. In addition to his 12,792 first-class runs, Kippax scored over 7,000 runs at an average of 53 for his grade club Waverley.[1] Don Bradman summed up Kippax's place in Australian cricket during his career:

This beautiful and stylish player was unlucky to emerge on the horizon of big cricket at a time when NSW had virtually an international side for its State XI. When his opportunity did come, Alan proved a real stalwart. In addition, his Trumperian style must have influenced for good vast numbers of young boys. Unquestionably, the line of Trumper and Kippax has much to do with the grace and elegance which is more frequently associated with players from NSW than from other States.[50]

Kippax captained NSW in 45 first-class matches, winning 19, drawing 17 and losing only nine.[3] His commentary of the fourth Test at Adelaide in early 1937 via a radio-telephone service made history as the first direct radio broadcast of a cricket match from Australia to England.[51]

Personal life

After a period working as a clerk, Kippax opened a sports store in Martin Place, Sydney during 1926. It became a very profitable business. Two years later, on 20 April 1928 at St Stephen's Presbyterian Church, he married Mabel Charlotte Catts. The New South Wales Cricket Association elected him a life member in 1943–44.[1] In February 1949, Kippax was awarded a joint testimonial with his old teammate, wicketkeeper Bert Oldfield. Played between Lindsay Hassett's XI and Arthur Morris's XI at the SCG, the match raised £6,030, which was split evenly between Kippax and Oldfield.[52] In later years, Kippax was an A-grade golfer at The Lakes course in Sydney and a club champion lawn bowler at Double Bay.[3]

A "... small, gentle man with a kindly way about him",[8] Kippax enjoyed a great reputation within the game; he was "a man of personal charm".[53] He was as elegant off the field as he was on; the cricket writer David Frith recorded that, "to visit him in his Bellevue Hill home was to be transported into a calm 1930s world of silk smoking jacket, cigarette holder and art deco trimmings."[54] Kippax died of heart disease at his home in Bellevue Hill on 5 September 1972. The Kippax Centre in the Canberra suburb of Holt is named after him.[1]

He was an uncle of the theatre critic H. G. Kippax.[55]

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Andrews (1983), pp 606–07.

- ↑ "Kippax, Alan Falconer Born 25 May 1897 Died 5 September 1972". cricinfom.com. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Cashman et al. (1996), pp 290–91.

- ↑ "Our History". Eastern Suburbs Cricket Club. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- ↑ Pollard, p 280.

- ↑ "Australian First-Class Season 1922/23: Highest Batting Averages". cricinfom.com. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- ↑ Pollard (1995), p 196.

- 1 2 McGilvray (1985), p 43.

- ↑ Robinson (1985), p 53.

- ↑ "Australian Domestic Season, 1924-25". cricinfom.com. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- ↑ Whitington (1974), pp 138–39.

- ↑ "Australia v England 1924-25". Wisden. 1931. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- ↑ "Full Scorecard of Australia vs England 5th Test 1925". ESPN cricket info.

- ↑ Harte (1993), p 298.

- ↑ Harte (1993), p 299.

- ↑ Harte (1993), pp 300–01.

- ↑ Bradman (1950), p 24.

- ↑ "Australian First-Class Season 1927/28: Highest Batting Averages". Cricinfo.com. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- ↑ Pollard (1995), p 281.

- ↑ Whitington (1974), p 143.

- ↑ Williamson, Martin (25 December 2004). "Festive frolics at the MCG". Cricinfo.com. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- 1 2 Robinson (1985), p 55.

- ↑ Lane, Tim (6 November 2004). "Tailend tale may eclipse Diva's triumph". The Age. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- ↑ Whitington (1974), p 145.

- ↑ Robinson (1985), p 54.

- ↑ "Australian First-Class Season 1929/30: Highest Batting Averages". Cricinfo.com. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- ↑ Pollard (1995), p 90.

- ↑ Cashman et al. (1996), p 290.

- ↑ Southerton, S.J. (1931). "The Australian team in England 1930". Wisden. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- ↑ Preston, Hubert (1931). "The West Indies in Australia 1930-31". Wisden. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- ↑ "Alan Kippax – The Style Was The Man | Cricket Web". www.cricketweb.net. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- 1 2 Bradman (1950), p 46.

- 1 2 Frith (2002), p 119.

- ↑ Whitington (1974), p 161.

- ↑ "Australian First-Class Season 1931/32: Batting Averages". Cricinfo.com. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- ↑ Harte (1996), p 337.

- ↑ Harte (1993), p 339.

- ↑ Frith (2002), p 105.

- ↑ Frith (2002), p 131.

- ↑ Whitington (1974), p 169.

- ↑ Robinson (1985), p 57.

- ↑ Frith (2002), p 435.

- ↑ Frith (2002), pp 112–13.

- ↑ Frith (2002), p 379.

- ↑ "Australian First-Class Season 1933/34: Batting Averages". Cricinfo.com. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- ↑ Cashman et al. (1996), p 65.

- 1 2 Southerton, S. J. (1935). "The Australian team in England, 1934". Wisden. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- ↑ Bradman (1950), p 85.

- ↑ Marshallsea, Trevor (5 June 2004). "Tassie pluck run-machine Bevan, once the apple of NSW's eye". Fairfax Digital. Retrieved 12 August 2007. Sydney Morning Herald. Accessed 12 July 2007.

- ↑ Bradman (1950), p 79.

- ↑ Harte (1993), p 373.

- ↑ Harte (1993), p 408.

- ↑ "Alan Kippax". Cricinfo.com. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- ↑ Frith (2002), p 423–24.

- ↑ Valerie Lawson, "A student of life's drama", Sydney Morning Herald, 21 October 2006; Retrieved 11 September 2019.

Sources

Media related to Alan Kippax at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Alan Kippax at Wikimedia Commons

- Andrews, BG (1983): “Kippax, Alan Falconer (1897–1972)”, Australian Dictionary of Biography - Volume 9, Melbourne University Press.

- Bradman, Don (1950): Farewell to Cricket, 1988 Pavilion Library reprint. ISBN 1-85145-225-7.

- Cashman, Richard et al., editors (1996): The Oxford Companion to Australian Cricket, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-553575-8.

- Frith, David (2002): Bodyline Autopsy, ABC Books. ISBN 0-7333-1321-3.

- Harte, Chris (1993): A History of Australian Cricket, Andre Deutsch. ISBN 0-233-98825-4.

- McGilvray, Alan & Tasker, Norman (1985): The Game Is Not the Same, ABC Books. ISBN 978-0-642-52738-7.

- Pollard, Jack (1995): Home and Away—A Complete Record of Australian Cricket Tours, ABC Books. ISBN 0-7333-0449-4.

- Robinson, Ray (1985): After Stumps Were Drawn, Williams Collins. ISBN 0-00-216583-X.

- Whitington, RS (1974): The Book of Australian Test Cricket 1877–1974, Wren Publishing. ISBN 0-85885-197-0.

- Wisden Cricketers' Almanack: various editions accessed at cricinfo.com.