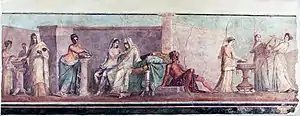

The so-called Aldobrandini Wedding (Nozze Aldobrandini) fresco is an influential Ancient Roman painting, of the second half of the 1st century BC, on display in the Vatican Museum. It depicts a wedding along with several mythological figures.

History

The fresco was discovered about the year 1600 from the masonry of a house near the Arch of Gallienus on the Esquiline Hill. It was in possession of the Aldobrandini family until 1818, when it was purchased by the Vatican authorities. Until the 19th century, this was one of the few and most influential paintings from the early Roman empire, and generated much interest and scholarship, including engravings by Pietro Santi Bartoli (1635–1700), and attention by Winckelmann, Karl Böttiger, and others. There are many elaborate competing interpretations of the scene.[1][2][3]

Description, interpretation and style

The painting, broken at both ends, is part of a frieze decorating a wall in the third style of a domus of the Esquiline Hill. It did not occupy the central position of the decoration, but was at the top of the wall on which it was painted.

Ten people appear in the painting, in three groups, whose action takes place both indoors and outdoors. At the left and in the middle, walls in the background indicate that the characters are indoors, while at right the background is the sky, indicating events taking place outside the same household. The threshold of the house appears between these scenes, in the lower center.

In the scene on the left, a Roman matron with white cloak, veiled head and flabellum, appears to test the temperature of the water poured into a small washing lustral supported by a pedestal, from which hangs a towel and in which a maid seems to pour more water. In the background a person carries an elongated object which is not well defined, perhaps a stool. At the foot of the column is an object made of overlapping tablets, probably a cassette.

In the central scene, bordered by a pillar between two walls on the left and the threshold of the house on the right, a woman wearing sandals with legs crossed (perhaps Charis, or, more likely, Peitho, goddess of persuasion) leans against a pillar, and pours essences from an alabastron over a shell supported by her left hand. On a cloth-covered bed sits the bride, with head veiled and dressed in a white coat and yellow shoes. Another female figure (Venus), bare-chested and wearing sandals, affectionately embraces the bride and raises her hand to the bride's face. At the foot of the bed a young half-naked man (Hymen, god of marriage), with a cloak wrapped around his waist and head wreathed with ivy, lies on the doorstep and observes the scene that takes place at his right.

In the far right scene, outdoors, three young women stand around an incense burner supported by a tripod. One, wearing a headdress, pours the essences from a patera, a second wearing a radiated crown of leaves turns towards the third, who holds a seven string lyre and plectrum. This group may represent the Three Muses.

The classic interpretation of the work, devised by the classical scholar Winckelmann, is that the scene depicts the wedding of Peleus and Thetis, parents of the hero Achilles. A second hypothesis, formulated in the 18th century by Luigi Dutens, is that the scene is the marriage of Alexander the Great and Roxana. These interpretations were pre-eminent until 1994, when Frank Müller proposed a scene from the play Hippolytus by Euripides as a guide for the correct reading of the fresco. Others have proposed some passages of Alcestis as defining the scene.

Setting aside these mythologic-literary interpretations, it is clear that the sequence relates to a wedding, with a focus on the universal anxiety experienced by a young bride, comforted and supported by Venus, waiting to meet the bridegroom and lose her virginity. The two side scenes help to integrate this interpretation; the scene on the left, with the matron that controls the temperature of the water in the basin, probably alludes to the ceremony of accepting the bride in her husband's house (aqua et igni accipi, acceptance of water and fire) according to the Roman tradition of deductio in domum mariti, while the scene on the right, is interpreted as a sacrifice for auspicious fortune, possibly in the presence of the recumbent god (Hymen) as the lyre plays the wedding song that accompanied the bride into her new home.

The formal language and style of the work suggest the work dates to the early Augustan age.

References

- ↑ Abstract from Euripides' Alcestis and the "Aldobrandini Wedding" , by Ross Kilpatrick.

- ↑ see The Early Augustan "Aldobrandini Wedding" Fresco: A Quartercentury Reinterpretation, article Memoirs of American Academy in Rome, 2002, Ross Kilpatrick, Queens University.

- ↑ Abstract from thesis: The history and interpretation of the "Aldobrandini Wedding": Bacchus, fertility and marriage in the time of Augustus. by DuRette, B. Underwood, Florida State University.

Further reading

- Frank G. J. M. Müller: The So-Called Aldobrandini Wedding. Research from the Years 1990 to 2016. (2019. FM Art Publications) ISBN 9789088907371