Sandro Pertini | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

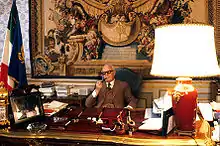

Pertini in 1978 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| President of Italy | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 9 July 1978 – 29 June 1985 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | Giulio Andreotti Francesco Cossiga Arnaldo Forlani Giovanni Spadolini Amintore Fanfani Bettino Craxi | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Giovanni Leone | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Francesco Cossiga | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| President of the Chamber of Deputies | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 5 June 1968 – 4 July 1976 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Brunetto Bucciarelli-Ducci | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Pietro Ingrao | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Secretary of the Italian Socialist Party | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 1 August 1945 – 18 December 1945 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Pietro Nenni | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Rodolfo Morandi | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Alessandro Pertini 25 September 1896 Stella, Kingdom of Italy | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 24 February 1990 (aged 93) Rome, Italy | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | PSU (1924–1930) PSI (1930–1990) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | University of Genoa University of Modena and Reggio Emilia University of Florence | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Alessandro "Sandro" Pertini OMCA (Italian: [(ales)ˈsandro perˈtiːni]; 25 September 1896 – 24 February 1990)[2] was an Italian socialist politician who served as the president of Italy from 1978 to 1985.[3]

Early life

Born in Stella (Province of Savona) as the son of a wealthy landowner, Alberto, he studied at a Salesian college in Varazze, and completed his schooling at the "Chiabrera" lyceum (high school) in Savona.

His philosophy teacher was Adelchi Baratono, a reformist socialist who contributed to his approach to socialism and probably introduced him to the inner circles of the Ligurian labour movements. Pertini obtained a law degree from the University of Genoa.

Aged 19 when Italy entered World War I on the side of the Triple Entente, Pertini opposed the war, but nonetheless enlisted in the army where he served as a lieutenant and was decorated for bravery. After the armistice in 1918, he joined the Unitary Socialist Party, PSU, then he settled in Florence where he also graduated in political science with a thesis entitled La Cooperazione ("Cooperation"; 1924). While in the city, Pertini also came into contact with people such as Gaetano Salvemini, the brothers Carlo and Nello Rosselli, and Ernesto Rossi. Pertini was physically beaten by Fascist squads on several occasions, but never lost faith in his ideals.

Resistance to Fascism

After the assassination of PSU leader Giacomo Matteotti by Fascists in 1924, Pertini became even more committed to the struggle against the totalitarian regime. In 1926, he was sentenced to internment but managed to go into hiding. Later, together with Carlo Rosselli and Ferruccio Parri, he organized and accompanied the escape to France of Filippo Turati, who was the most prominent figure of the PSU. Pertini remained in the country until 1926 working as a mason. According to the Italian historian of Freemasonry Aldo Alessandro Mola, during that period Pertini had relationships with exponents of the Grand Orient of Italy who were in exile in France.[4] This hypothesis seems unsupported by known documents from archives. On his return to Italy, he was arrested in Pisa, tried, and sentenced to ten years' imprisonment.

In 1935 he was interned on Santo Stefano Island, Ventotene (LT), Pontine Islands, an island in the Tyrrhenian Sea, where he remained through Italy's entry into World War II and until 1943. Although he had begun suffering from severe illness, Pertini never demanded pardon. He was released a month after Benito Mussolini's arrest and joined the Italian resistance movement against the Nazi German occupiers and Mussolini's new regime – the Italian Social Republic. Arrested by the Germans, he was sentenced to death but freed by a partisan raid. Pertini then travelled north to organize partisan war as an executive member of PSI (alongside Rodolfo Morandi and Lelio Basso). He had a primary role in the Milan uprising of 25 April 1945, which led to the execution of Mussolini.

Prominence

After the war ended in Italy on 25 April 1945 and the monarchy was abolished through the 1946 Italian constitutional referendum, Pertini was elected to the Constituent Assembly (La Costituente), the body that prepared the new republican Italian Constitution. In the postwar era, he was a prominent member of the directive board of the Italian Socialist Party (the PSI, which the PSU had rejoined).

In spite of his intransigent attitude toward the Italian Communist Party, Pertini was suspicious of many policies enforced by the PSI. He criticized all forms of colonialism, as well as corruption in the Italian state and within the Socialist Party, where he kept an independent political position.

He was elected president of the Italian Chamber of Deputies in 1968.[5]

President (1978–1985)

In 1978, the 81-year-old Pertini was elected President of the Italian Republic, the highest office in the nation. Despite his advanced age, he displayed considerable energy and vigour, playing a major role in helping restore the public's faith in the government and institutions of Italy, as well as maintaining an active schedule of travelling and meeting foreign dignitaries. During the Brigate Rosse terrorism period of the Anni di piombo, Pertini openly denounced the violence. He also opposed organized crime in Italy, South African apartheid, Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet and other dictatorial regimes, as well as the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

In 1981, Pertini presided over the formation of the government by Giovanni Spadolini, the first non Christian Democratic Italian government since the time of De Gasperi.

In 1985, he stepped down from the presidency, becoming automatically senator for life. The only official role he accepted in his retirement was President of the "Filippo Turati" Foundation for Historical Studies of Florence inaugurated in 1985 and dedicated to recording and preserving the history of the socialist movement in Italy. In December 1988 Pertini was the first person to be awarded the Otto Hahn Peace Medal in Gold by the United Nations Association of Germany (Deutsche Gesellschaft für die Vereinten Nationen, DGVN) in Berlin, "for outstanding services to peace and international understanding, especially for his political ethics and practical humanity". Pertini died in February 1990 at the age of 93 and was mourned across the nation.

1982 World Cup Final

Pertini attended the 1982 World Cup Final in Madrid for a match between Italy and West Germany just two days after the fourth anniversary of his inauguration. After Italy scored their third goal, he wagged his finger to either the German delegation or King Juan Carlos I, and said "they [the German team] will not catch us any more".[6] Memorable images from the event are Pertini standing on his chair at Santiago Bernabeu stadium, exulting in the Italian victory, and the card game on the return flight, between the president and three team members (trainer Bearzot and players Causio and Zoff), the world cup trophy next to them on the table.

Paolo Rossi, Italy's and the tournament's top scorer, later said: "I remember that when he welcomed us at the Presidential Palace after our win, he rose and said: 'This is my best day as President.'"[7]

Relationship with Pope John Paul II

Sandro Pertini had a close friendship with Pope John Paul II, with whom he met often both for official and private occasions, and had frequent phone conversations. In "Accanto a Giovanni Paolo II", he is known to have referred to his mother looking over him in heaven, moved that her atheist son was friends with the Pope.

On 13 May 1981, he went to the Gemelli Hospital as soon as he heard that the Pope had been shot, and stayed until late in the night when he was told that the Pope was not in danger anymore. He recalled the event later that year in the annual New Year's Eve Presidential Address to the Italian People.[8]

Honours and awards

In 1986, he received the Freedom medal.[9] On 11 October 1979, President of Yugoslavia Tito awarded Pertini the Order of the Yugoslav Great Star.[10]

In popular culture

In the 1975 film Last Days of Mussolini by Carlo Lizzani, there is a character inspired by Pertini, performed by Sergio Graziani.[11] In early 1980s, Andrea Pazienza created the comic book series Il Partigiano Pert ("The Partisan Pert"), a comedy strip portraying Pertini during World War II with the same cartoonist as his helper.[12][13][14]

Pertini has been mentioned in some verses of several Italian songs, as in Sotto la pioggia ("under the rain", 1982) by Antonello Venditti, Babbo Rock ("Daddy Rock", 1982) by the Skiantos, L'Italiano ("The Italian", 1983) by Toto Cutugno, Caro Presidente ("Dear President", 1984) by Daniele Shook, Pertini Dance (1984) by the S.C.O.R.T.A., Pertini Is A Genius, Mirinzini Is Not Famous (2007) by the Ex-Otago.[15][16]

Electoral history

| Election | House | Constituency | Party | Votes | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1946 | Constituent Assembly | Genoa–Imperia–La Spezia–Savona | PSIUP | 27,870 | ||

| 1953 | Chamber of Deputies | Genoa–Imperia–La Spezia–Savona | PSI | 22,802 | ||

| 1958 | Chamber of Deputies | Genoa–Imperia–La Spezia–Savona | PSI | 19,966 | ||

| 1963 | Chamber of Deputies | Genoa–Imperia–La Spezia–Savona | PSI | 22,579 | ||

| 1968 | Chamber of Deputies | Genoa–Imperia–La Spezia–Savona | PSI | 24,235 | ||

| 1972 | Chamber of Deputies | Genoa–Imperia–La Spezia–Savona | PSI | 53,657 | ||

| 1976 | Chamber of Deputies | Genoa–Imperia–La Spezia–Savona | PSI | 35,506 | ||

References

- ↑ As a member of the Constituent Assembly of Italy, he was automatically nominated senator.

- ↑ Ferrarová, E.; Ferrarová, M.; Pospíšilová, V. (2017). Italština pro samouky a věčné začátečníky (in Czech). p. 387. ISBN 978-80-266-0745-8.

- ↑ "Alessandro Pertini". Britannica. 21 September 2023.

- ↑ Aldo Mola, Storia della massoneria italiana Dalle origini ai nostri giorni, Milan. Bompiani, 1992, pp. 782-783. OCLC 463003899, FRBNF38774140.

- ↑ With the ardor of those who drove merchants from the temple, Speaker Pertini ordered to drive away the "whips" from the aisle, accelerating the outcome of the presidential election in 1971 : Buonomo, Giampiero (2015). "Il rugby e l'immortalità del nome". L'Ago e Il Filo. Archived from the original on 1 August 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ↑ Video on Pertini exulting at the Italian team's victory on YouTube

- ↑ Article on emagazine.credit-suisse.com Archived 19 January 2013 at archive.today

- ↑ "Presidential Address of New Year's Eve 1981". The official website of the Presidency of the Italian Republic.

- ↑ Blair, William G. (5 March 1986). "PALME IS NAMED A RECIPIENT OF AN F.D.R. FREEDOM MEDAL". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ↑ "Svečana večera u čast Pertinija". Slobodna Dalmacija (10738): 12. 12 October 1979.

- ↑ (in Italian) "Lizzani: Pertini wrote to me that Audisio didn't shoot the Duce" (La Provincia)

- ↑ (in Italian) "Il Partigiano Pert" Archived 29 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine (lastoriasiamonoi.rai.it)

- ↑ (in Italian) "Pertini, the partisan president in the amazing comics of Andrea Pazienza" (slumberland.it)

- ↑ (in Italian) "Pertini" on andreapazienza.it Archived 4 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ (in Italian) "The 5 best songs dedicated to Sandro Pertini" (orrorea33giri.com)

- ↑ (in Italian) "Sandro Pertini, our president ever, historical figure and man" (quotidianpost.it)