Antonio Segni | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

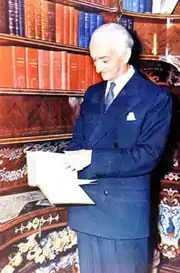

Official portrait, 1962 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President of Italy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 11 May 1962 – 6 December 1964 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | Amintore Fanfani Giovanni Leone Aldo Moro | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Giovanni Gronchi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Giuseppe Saragat | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister of Italy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 16 February 1959 – 26 March 1960 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President | Giovanni Gronchi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Amintore Fanfani | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Fernando Tambroni | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 6 July 1955 – 20 May 1957 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President | Giovanni Gronchi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy | Giuseppe Saragat | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Mario Scelba | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Adone Zoli | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy Prime Minister of Italy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 2 July 1958 – 16 February 1959 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | Amintore Fanfani | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Giuseppe Pella | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Attilio Piccioni | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 2 February 1891 Sassari, Kingdom of Italy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 1 December 1972 (aged 81) Rome, Italy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | PPI (1919–1926) DC (1943–1972) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse |

Laura Carta Camprino

(m. 1921) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 4 (including Mario) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Awards | Charlemagne Prize | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Antonio Segni (Italian pronunciation: [anˈtɔːnjo ˈseɲɲi] ⓘ; 2 February 1891 – 1 December 1972) was an Italian politician and statesman who served as the president of Italy from May 1962 to December 1964, and as the prime minister of Italy in two distinct terms between 1955 and 1960.[1]

A member of the Christian Democracy party, Segni held numerous prominent offices in Italy's post-war period, serving as the country's Minister of Foreign Affairs, Interior, Defence, Agriculture, and Public Education. He was the first Sardinian to become head of state and government. He was also the second shortest-serving president in the history of the Republic and the first to resign from office due to illness.[2]

Early life

Segni was born in Sassari in 1891. His father, Celestino Segni, was a lawyer and professor at the University of Sassari, while his mother, Annetta Campus, was a housewife. He grew up in a well-off family, involved in Sardinian politics; his father served as municipal and provincial councilor for Sassari, as well as deputy mayor during the early 1910s.[3] He began studying at the University of Sassari, where he would found a section of Azione Cattolica Italiana.[4]

In 1913, Segni graduated with merit at the University of Sassari, with the thesis Il vadimonium on civil procedure in Roman law.[4] He completed his studies in Rome with Giuseppe Chiovenda, of which he became the favorite student; in the law firm of the jurist, he met Piero Calamandrei, with whom he built a close friendship that would last a lifetime.[5]

When the World War I broke out, Segni was enlisted as an artillery officer. Discharged, after some months, he continued his profession as lawyer, specializing in civil procedure. In 1920, he started his academic career as law professor at the University of Perugia. In 1921, he married Laura Carta Caprino, daughter of a rich landowner,[6] with whom he had four children,[7] including Mario, who would become a prominent politician during the early 1990s.[8][9]

During these years, Segni started his involvement in politics. In 1919, he joined the Italian People's Party (PPI), a Christian democratic party, led by Don Luigi Sturzo.[10] In 1923, he was appointed in party's national council. Segni ran in the 1924 Italian general election for Sardinia's constituency but was not elected.[11] He remained a member of the PPI until all political organizations were dissolved by Benito Mussolini two years later in 1926. For the next 17 years, Segni left political life, continuing to teach civil procedure and agrarian law at the universities of Pavia, Perugia, Cagliari, and Sassari, where he later served as rector from 1946 to 1951.[12]

Early political career

In 1943, after the fall of Mussolini's Fascist regime, Segni was one of the founders of Christian Democracy (DC), the heir of the PPI.[13] On 12 December 1944, he was appointed Undersecretary to the Ministry of Agriculture in the second Bonomi government.[14]

Minister of Agriculture

In the 1946 Italian general election, Segni was elected to the Constituent Assembly for the consistency of Cagliari–Sassari–Nuoro, receiving more than 40,000 votes.[15] On 13 July 1946, he was appointed Minister of Agriculture in the second De Gasperi government.[16] As minister, he primarily focused on the growth of agricultural production, functional to improving Italy's conditions after the end of the war. Segni tried to reform agricultural contracts but was strongly opposed by conservatives and by many members of the DC. The failure of this legislative proposal accelerated the timing of the development of the land reform.[17]

The land reform, approved by the Italian Parliament in October 1950, was financed in part by the funds of the Marshall Plan launched by the United States in 1947 and considered by some scholars as the most important reform of the entire post-war period.[18] Segni's reform proposed, through forced expropriation, the distribution of land to agricultural labourers, thus making them small entrepreneurs and no longer subject to the large landowner.[19] If in some ways the reform had this beneficial result, for others it significantly reduced the size of farms, effectively removing any possibility of transforming them into advanced businesses. This negative element was mitigated and in some cases eliminated by forms of cooperatives.[20]

Segni, who was a landowner, ordered the expropriation of most of his own estate in Sardinia.[21] He became known as a "white Bolshevik" for his agrarian reforms.[22] Modern historians assert that landowners were instead favoured by Segni, and his decrees allowed them to reclaim land that had been granted to the peasantry by the preceding administration.[23]

Minister of Public Education

In July 1951, after a cabinet reshuffle, Segni left his office as Minister of Agriculture and was appointed the Italian Minister of Public Education in De Gasperi's seventh government, succeeding Guido Gonella.[24]

As minister, Segni was particularly involved in the fight against illiteracy, in the improvement of teaching activities, and in the construction of new schools around the country; however, he did not continue the important reforms started by his predecessor. He tried to implement the reform step by step but encountered strong resistance, even in the ministries that were supposed to finance these measures. Segni proposed to replace the high school exam with an admission test to university, but this was rejected.[25] His reforms, which also received various appreciations from the opposition parties due to his secular idea of school that was very different from that of Gonella, were not ambitious as the ones of his predecessor.[26]

The 1953 Italian general election was characterised by changes in the electoral law. Even if the general structure remained uncorrupted, the government introduced a majority bonus system of two-thirds of seats in the country's Chamber of Deputies for the coalition that would obtain at-large the absolute majority of votes. The change was strongly opposed by both the opposition parties and DC's smaller coalition partners that had no realistic chance of success under this system. The new law was called the scam law by its detractors,[27] including some dissidents of minor government parties who founded special opposition groups to deny the artificial landslide victory of the DC.

The campaign of the opposition to the electoral law achieved its goal, as the government coalition won 49.9% of national vote, just a few thousand votes of the threshold for a supermajority, resulting in an ordinary proportional distribution of the seats. Technically, the government won the election, winning a clear working majority of seats in both houses. In July 1953, Segni was ousted from office in the newly formed government of Alcide De Gasperi.[28] Frustration with the failure to win a supermajority caused significant tensions in the leading coalition, and De Gasperi was forced to resign by the Italian Parliament on 2 August.[29] On 17 August, Italian president Luigi Einaudi appointed Pella as new prime minister, who selected Segni as his Minister of Public Education.[30] Pella remained in power only for five months.[31][32] In the successive governments of Amintore Fanfani and Mario Scelba, Segni was not appointed in any office.[33]

Prime Minister of Italy

In the 1955 Italian presidential election held on 28–29 April of that year, Giovanni Gronchi was elected the new president of the Republic.[34] After the election, a political crisis between prime minister Scelba and DC's leader Fanfani broke out.[35] In July 1955, Scelba resigned from the office, and Segni received the task of forming a new cabinet.[36] He started consultations with parties to explore the possibilities of forming a new coalition government, obtaining the approval of DC, Italian Democratic Socialist Party (PSDI) and Italian Liberal Party (PLI), and the external support from the Italian Republican Party (PRI). On 6 July, Segni sworn in as the new prime minister. On 18 July, the government's program was approved by the Chamber of Deputies with 293 votes in favour and 265 against. On 22 July, the Senate of the Republic approved the confidence vote with 121 votes in favour and 100 against.[37]

First government

Segni's first government is widely considered among the most important cabinets in the history of the Republic.[38] During his premiership, in 1955, Italy became a member of the United Nations (UN) in 1955.[39] In March 1957, Segni signed the Treaty of Rome, which brought about the creation of the European Economic Community (EEC), between Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany.[40] The Treaty of Rome still remains one of the two most important treaties in the modern-day European Union (EU).[41]

Segni had always been a strong supporter of European integration; according to him, in a world governed by great powers, European unity was the only possible way to influence the world. He also strengthened relations with West Germany, becoming a close friend of Konrad Adenauer.[42] As premier, he also had to face the complicated Suez crisis of 1956, in which he staunchly defended Italy's economic interests in the area, always bearing in mind the need to safeguard Atlantic and European solidarity.[43]

During his premiership, Segni often had conflict with Fanfani, who believed that the government should have a more critical attitude towards the Anglo-French choices. Moreover, the brutal Soviet repression of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 further divided Segni and Fanfani. Segni opposed an anti-communist legislative intervention, as Fanfani asked. The clash between the two leaders was so bitter that Segni threatened to resign. In his diary, Segni wrote: "The events of Hungary are unfortunately subjected to repressive political speculation. I refuse to speculate on them."[44]

In domestic policy, Segni's government was particularly active in judiciary policies. A law established the National Council of Economy and Labour (CNEL), as well as the Superior Council of the Judiciary. The most important event of all was the official opening of the Constitutional Court of Italy.[45] In 1957, political tensions arose between the Italian president Gronchi and foreign affairs minister Gaetano Martino, regarding government's foreign policy. In May 1957, the PSDI withdrew its support for the government, and Segni resigned on 6 May.[46] On 20 May, Adone Zoli sworn in as new head of government.[47]

After the premiership

In July 1958, Zoli resigned, after having lost his majority in the Italian Parliament, and Fanfani became the prime minister again. Segni was appointed Deputy Prime Minister of Italy and the country's Minister of Defence.[48]

As minister, Segni worked to represent the interests of the Italian Armed Forces, increasing wages and social securities for retired veterans, as well as strengthening military equipment and weapons.[49] He also accepted NATO missile bases for atomic weapons, convinced that they were a necessary tool to ensure the defence of Italy more than a danger that exposed the country to possible reprisals.[50]

In January 1959, a conspicuous group of Christian Democrats started voting against their own government, forcing Fanfani to resign on 26 January 1959 after six months in power.[51]

Second government

In February 1959, Gronchi gave Segni the task of forming a new cabinet, and he officially sworn in as the new prime minister on 16 February.[52] Segni formed a one-party government, which was composed only by DC members, and was externally supported by minor centre-right and right-wing parties, as well as the neo-fascist Italian Social Movement (MSI).[53]

Segni attempted to strengthen Atlantic solidarity and to present Italy as Europe's most reliable ally of the United States. He also tried to represent the reassuring alternative to Fanfani's resourcefulness, advocating for Atlanticism in a season characterized by openings to the left, which was supported by Fanfani. The most comforting signals came from the economy, as industry and commerce expanded, unemployment declined, and Italy's GDP grew by over 6%, a rhythm that placed it among the most dynamic countries in the world.[54]

In social policy, various reforms in social welfare were carried out. A law of 21 March 1959 extended insurance against occupational diseases to agricultural workers, while a law approved on 17 May 1959 introduced a special additional indemnity for retired civil servants. Another important law, dated 4 July 1959, extended pension insurance to all artisans.[55]

In March 1960, the PLI withdrew its support to his government and Segni was forced to resign. After few months of Fernando Tambroni's government, Fanfani returned to the premiership on 26 July, this time with an openly centre-left program supported by the PSI abstention, and Segni was appointed Minister of Foreign Affairs.[56] In August 1961, Segni and Fanfani made an historic trip to Moscow to meet the Soviet leaders.[57]

President of Italy

In May 1962, when Gronchi's term as president of Italy expired, Segni was proposed as the DC's candidate by new party's leader Aldo Moro for the 1962 presidential election held on 2–6 May. With Segni's choice, Moro wanted to reassure the conservative representatives of his own party, worried about a possible extreme shift on leftist stances, after the beginning of the organic centre-left period in February 1962.[58] On the first two rounds, the Italian Communist Party (PCI) decided to vote for Umberto Terracini, while the PSI supported Sandro Pertini. After the third round, the PCI and PSI decided to converge on the candidacy of the PSDI, Giuseppe Saragat, who gained also the favor of some DC representatives.[59]

After several ballots, Segni was finally elected president on 6 May 1962 with 51% of the votes, 443 votes on a total 854 electors.[60][61] His election was allowed thanks to the votes of monarchist and neo-fascist representatives.[62] It was the first time that DC's official candidate succeeded in being elected president of the Republic.[63]

Many influent entities, notably including the Bank of Italy, the Armed Forces, Vatican hierarchies, as well as economic and financial world, were concerned about the entry of the PSI into the government, and considered Segni a reference of stability and their most prominent political landmark. His power grew further in the aftermath of the 1963 Italian general election, which was characterized by a loss for the DC due to its new leftist policies.[64] Despite Segni's opposition, at the end of the year, Moro and the PSI secretary Pietro Nenni launched their first centre-left government, ruling the country for more than four years.[65]

Vajont Dam disaster

As president, Segni had to face one of the most tragic events in Italian republican history, namely the Vajont Dam disaster.[66] On 9 October 1963, a landslide occurred on Monte Toc, in the province of Pordenone. The landslide caused a megatsunami in the artificial lake in which 50 million cubic metres of water overtopped the dam in a wave of 250 metres (820 ft), leading to the complete destruction of several villages and towns, and 1,917 deaths.[67] In the previous months, the Adriatic Society of Electricity (SADE) and the Italian government, which both owned the dam, dismissed evidence and concealed reports describing the geological instability of Monte Toc on the southern side of the basin and other early warning signs reported prior to the disaster.[68]

On the following day, Segni visited the affected areas, promising justice for the victims.[69] Immediately after the disaster, both the government and local authorities insisted on attributing the tragedy to an unexpected and unavoidable natural event. Despite these statements, numerous warnings, signs of danger, and negative appraisals had been disregarded in the previous months and the eventual attempt to safely control the landslide into the lake by lowering its level came when the landslide was almost imminent and was too late to prevent it.[70] The communist newspaper l'Unità was the first to denounce the actions of management and government.[71] The DC accused the PCI of political profiteering from the tragedy and then-prime minister Giovanni Leone promised to bring justice to the people killed in the disaster. A few months after the end of his premiership, he became the head of SADE's team of lawyers, who significantly reduced the amount of compensation for the survivors and ruled out payment for at least 600 victims.[72]

1964 coalition crisis

On 25 June 1964, the government of Aldo Moro was beaten on the budget law for the Italian Ministry of Education concerning the financing of private education, and on the same day Moro resigned. During the presidential consultations for the formation of a new cabinet, Segni asked Nenni to exit from the government majority.[73]

On 16 July, Segni sent the Carabinieri General Giovanni De Lorenzo to a meeting of representatives of the DC, to deliver a message in case the negotiations around the formation of a new centre-left government would fail. According to some historians, De Lorenzo reported that Segni was ready to give a subsequent mandate to Cesare Merzagora, the president of the Senate, asking him of forming a president's government composed by all the conservative forces in the Italian Parliament.[74][75] Ultimately, Moro managed to form another centre-left majority. During the negotiations, Nenni had accepted the downsizing of his reform programs. On 17 July, Moro went to the Quirinal Palace, with the acceptance of the assignment and the list of ministers of his second government.[76]

Illness and resignation

On 7 August 1964, during a meeting at the Quirinal Palace with Moro and Saragat, Segni suffered a serious cerebral hemorrhage. At the time, he was 73 years old and the first prognosis was not positive.[77] In the interim, Merzagora served as Acting President of the Republic.[78] Segni only partially recovered and decided to retire from office on 6 December 1964.[79] Immediately after his resignation, Segni was appointed senator for life ex officio. The 1964 Italian presidential election resulted in the election of Saragat on 29 December.[80]

Death and legacy

On 1 December 1972, Segni died in Rome at the age of 81.[81]

During all his political career, Segni acted as a moderate conservative, staunchly opposing the "opening to the left" proposed by Fanfani and Moro, but he also tried not to bring his own party too far to the right.[82] He was the first Italian president to resign from office.[83]

The frail, often ailing Segni, was affectionately called il malato di ferro, which literally means "the iron invalid".[84] Time once quoted a friend of his: "He is like the Colosseum; he looks like a ruin but he'll be around for a long time."[63]

Controversies

During his presidency, Segni was particularly influenced by General Giovanni De Lorenzo, commander of the Carabinieri, a former partisan with monarchical ideals. On 25 March 1964, De Lorenzo met with Carabinieri's commanders of the divisions of Milan, Rome, and Naples, proposing a response to a hypothetical national crisis, known as Piano Solo.[85] The plan consisted of a set of measures to occupy certain institutions, such as Quirinal Palace in Rome, and essential media infrastructures, like television and radio, as well as the neutralisation of communist and socialist parties, with the deportation of hundreds of left-wing politicians to a secret military base in Sardinia.[86] The list of people to be deported also included intellectuals, such as Pier Paolo Pasolini.[87]

On 10 May, De Lorenzo presented his plan to Segni, who was particularly impressed by it. Journalists Giorgio Galli and Indro Montanelli believed that Segni did not really want to carry out a coup d'état, but that he wanted to use the plan like a threat for political purposes.[88][89] The coup plans were revealed in 1967, when the journalists Eugenio Scalfari and Lino Jannuzzi published the plan in the Italian news magazine L'Espresso in May 1967.[90] The results of the official investigation remained classified until the early 1990s. It was released by premier Giulio Andreotti to the parliamentary investigation into Operation Gladio. L'Espresso mentioned that some 20,000 Carabinieri were supposed to be deployed around the country, with more than 5,000 agents in Rome.[91] Segni was never investigated for this fact.[92]

Electoral history

| Election | House | Constituency | Party | Votes | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1924 | Chamber of Deputies | Sardinia | PPI | — | ||

| 1946 | Constituent Assembly | Cagliari–Sassari–Nuoro | DC | 40,394 | ||

| 1948 | Chamber of Deputies | Cagliari–Sassari–Nuoro | DC | 61,168 | ||

| 1953 | Chamber of Deputies | Cagliari–Sassari–Nuoro | DC | 77,306 | ||

| 1958 | Chamber of Deputies | Cagliari–Sassari–Nuoro | DC | 107,054 | ||

Presidential elections

| 1962 presidential election (9th ballot) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candidate | Supported by | Votes | % | |

| Antonio Segni | DC, MSI, PDIUM | 443 | 51.9 | |

| Giuseppe Saragat | PSDI, PSI, PCI, PRI | 334 | 39.1 | |

| Others / Invalid votes | 77 | 9.0 | ||

| Total | 854 | 100.0 | ||

See also

References

- ↑ Rizzo, Tito Lucrezio (2 October 2012). Parla il Capo dello Stato: sessanta anni di vita repubblicana attraverso il Quirinale 1946–2006 (in Italian). Gangemi Editore spa. ISBN 9788849274608.

- ↑ Dimissioni del Presidente della Repubblica, Panorama

- ↑ Antonio Segni, Dizionario Biografico, Enciclopedia Treccani

- 1 2 Gilbert, Mark; Nilsson, Robert K. (2 April 2010). The A to Z of Modern Italy. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-1-4616-7202-9.

- ↑ Antonio Segni, un europeista al Quirinale, La Nuova Sardegna

- ↑ Laura Carta Caprino, Getty

- ↑ "Accademia sarda di storia di cultura e di lingua » Blog Archive » Protagoniste del caritatismo cattolico sassarese (1856–1970) a cura di Angelino Tedde" (in Italian). Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ↑ Mariotto Segni, Enciclopedia Treccani

- ↑ "Celestino Segni". geni_family_tree. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ↑ Stanley G. Payne (1995). A History of Fascism, 1914–1945. Univ of Wisconsin Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-299-14874-4.

- ↑ Dieter Nohlen & Philip Stöver (2010) Elections in Europe: A data handbook, p1047 ISBN 978-3-8329-5609-7

- ↑ La Biografia del Presidente Segni, quirinale.it

- ↑ Gary Marks; Carole Wilson (1999). "National Parties and the Contestation of Europe". In T. Banchoff; Mitchell P. Smith (eds.). Legitimacy and the European Union. Taylor & Francis. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-415-18188-4. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ Governo Bonomi II, governo.it

- ↑ Elezioni del 1946: Collegio di Cagliari–Sassari–Nuoro, Ministero dell'Interno

- ↑ Governo De Gasperi II, governo.it

- ↑ La Riforma Agraria, Occupazione delle Terre

- ↑ Corrado Barberis, Teoria e storia della riforma agraria, Florence, Vallecchi, 1957

- ↑ Riforma agraria e modernizzazione rurale in Italia nel ventesimo secolo

- ↑ Alcide De Gasperi tra riforma agraria e guerra fredda (1948–1950)

- ↑ "Italy: New Man on the Job". Time. 1 July 1955. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ↑ Il colle più alto

- ↑ Ginsborg, Paul (2003). A History of Contemporary Italy: Society and Politics, 1943–1988, Palgrave Macmillan, p. 122ISBN 1-4039-6153-0

- ↑ VII Governo De Gasperi, camera.it

- ↑ Antonio Segni, Salvatore Mura, il Mulino

- ↑ Educazione, laicità e democrazia, Antonio Santoni

- ↑ Also its parliamentarian exam had a disruptive effect: "Among the iron pots of political forces that faced in the Cold War, Senate cracked as earthenware pot": Buonomo, Giampiero (2014). "Come il Senato si scoprì vaso di coccio". L'Ago e Il Filo. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ↑ Governo De Gasperi VIII, camera.it

- ↑ (in Italian) Come il Senato si scoprì vaso di coccio, in L’Ago e il filo, 2014

- ↑ Mattarella cita Einaudi e l'incarico a Pella: fu il primo governo del presidente

- ↑ Governo Pella, Governo.it

- ↑ Cattolico e risorgimentale, Pella e il caso di Trieste

- ↑ Composizione del Governo Scelba, senato.it

- ↑ "Danger on the Left", Time, 9 May 1955

- ↑ "Segni Hopeful of Breaking Up Crisis in Italy". 1 July 1955. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ↑ Governo Segni I, governo.it

- ↑ Il governo Segni I

- ↑ I primi passi della Presidenza Gronchi ed il governo Segni

- ↑ 60 anni dell'Italia all'ONU, Ministero degli Esteri

- ↑ Cosa sono i Trattati di Roma e perché sono importanti, il Post

- ↑ Trattati di Roma: cosa sono e perché sono stati celebrati, il Post

- ↑ Italia e mondo tedesco all'epoca di Adenauer

- ↑ La crisi di Suez e la fine del primato dell’Europa

- ↑ Diario (1956–1964), S. Mura, 2012, page 101)

- ↑ I primi due anni di funzionamento della Corte Costituzionale Italiana

- ↑ I Governo Segni, camera.it

- ↑ Governo Zoli, camera.it

- ↑ Governo Fanfani II, senato.it

- ↑ "Italy: Right Turn". Time. 2 March 1959. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ↑ L’Italia nella guerra fredda e i missili americani IRBM Jupiter, Debora Sorrenti

- ↑ Italy's Fanfan, Time, 16 June 1961

- ↑ II Governo Segni, Della Repubblica

- ↑ L'anima nera della Repubblica: storia del MSI

- ↑ Il miracolo economico italiano, Enciclopedia Treccani

- ↑ Growth to Limits: The Western European Welfare States Since World War II Volume 4 edited by Peter Flora

- ↑ III Legislatura: 12 giugno 1958 – 15 maggio 1963

- ↑ Fanfani e Segni al ritorno da Mosca, Archivio Luce

- ↑ Corsa al Colle: L'elezione di Antonio Segni (1962), Panorama

- ↑ Tutti i presidenti della Repubblica Italiana, la Repubblica

- ↑ L'elezione del Presidente Segni, quirinale.it

- ↑ Elezione a Presidente della Repubblica di Antonio Segni, camera.it

- ↑ La Repubblica italiana ha il suo terzo presidente

- 1 2 "Italy: Symbol of the Nation". Time. 1 May 1962. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ↑ Elezioni del 1963, Ministero dell'Interno

- ↑ I Governo Moro, governo.it

- ↑ Il 9 settembre 1963 il disastro del Vajont: commemorazioni in tutta la regione, Friuli Venezia Giulia

- ↑ "Vaiont Dam photos and virtual field trip". University of Wisconsin. Archived from the original on 29 July 2009. Retrieved 1 July 2009.

- ↑ La cronaca del disastro e il processo, ANSA

- ↑ Mauro Corona: «Una mano assassina lanciò il sasso che distrusse la mia Erto», Il Gazzettino

- ↑ La tragedia del Vajont Archived 9 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Rai Scuola

- ↑ "Mattolinimusic.com". Mattolinimusic.com. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- ↑ "Vajont, Due Volte Tragedia". Sopravvissutivajont.org. 9 October 2002. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- ↑ Indro Montanelli, Storia d'Italia Vol. 10, RCS Quotidiani, Milan, 2004, page 379-380.

- ↑ Gianni Flamini, L'Italia dei colpi di Stato, Newton Compton Editori, Rome, page 82.

- ↑ Sergio Romano, Cesare Merzagora: uno statista contro I partiti, in: Corriere della Sera, 14 marzo 2005.

- ↑ Governo Moro II, governo.it

- ↑ Segni, uomo solo tra sciabole e golpisti, Il Fatto Quotidiano

- ↑ Merzagora e Fanfani, supplenti del passato

- ↑ Il 6 dicembre 1964, Antonio Segni si dimette da presidente della Repubblica, L'Unione Sarda

- ↑ Giuseppe Saragat – Storia della Camera, camera.it

- ↑ Antonio Segni – Portale storico della Presidenza della Repubblica, quirinale.it

- ↑ Tra Segni e Moro braccio di ferro per la supremazia, La Nuova Sardegna

- ↑ Dimissioni di Segni e Leone. I precedenti, la Repubblica

- ↑ "Italy: Malato di Ferro". Time. 2 October 1964. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ↑ Marcus, George E. (1 March 1999). Paranoia Within Reason: A Casebook on Conspiracy as Explanation. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226504575.

- ↑ Gianni Flamini, L'Italia dei colpi di Stato, Newton Compton Editori, Rome, page 79

- ↑ Solo, Mister d'Italia

- ↑ Giorgio Galli, Affari di Stato, Edizioni Kaos, Milan, 1991, page 94

- ↑ Antonio Segni e il Piano Solo: una storia da riscrivere

- ↑ Cento Bull, Italian Neofascism, p. 4

- ↑ "Twenty-Six Years Later, Details of Planned Rightist Coup Emerge". Associated Press. 5 January 1991.

- ↑ Il Piano Solo? Non fu un golpe, Avvenire

- Marcus, George E. (1999). ‘'Paranoia Within Reason: A Casebook on Conspiracy as Explanation'’, Chicago: University of Chicago Press ISBN 0-226-50457-3

External links

- President Antonio Segni, Italian Chamber of Deputies

- Political factors related to the illness of Italian President Antonio Segni, declassified CIA document dated 14 August 1964

- Newspaper clippings about Antonio Segni in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

.svg.png.webp)