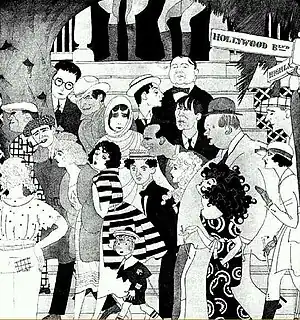

Alice Terry | |

|---|---|

Stars of the Photoplay, 1924 | |

| Born | Alice Frances Taaffe July 24, 1899 Vincennes, Indiana, U.S. |

| Died | December 22, 1987 (aged 88) Burbank, California, U.S. |

| Occupation | Actress |

| Years active | 1916–1933 |

| Spouse | |

Alice Frances Taaffe (July 24, 1899 – December 22, 1987), known professionally as Alice Terry, was an American film actress and director. She began her career during the silent film era, appearing in thirty-nine films between 1916 and 1933. While Terry's trademark look was her blonde hair, she was actually a brunette, and put on her first blonde wig in Hearts Are Trumps (1920) to look different from Francelia Billington, the other actress in the film. Terry played several different characters in the 1916 anti-war film Civilization, co-directed by Thomas H. Ince and Reginald Barker. Alice wore the blonde wig again in her most acclaimed role as "Marguerite" in film The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921), and kept the wig for any future roles. In 1925 her husband Rex Ingram co-directed Ben-Hur, filming parts of it in Italy. The two decided to move to the French Riviera, where they set up a small studio in Nice and made several films on location in North Africa, Spain, and Italy for MGM and others. In 1933, Terry made her last film appearance in Baroud, which she also co-directed with her husband.

Early years

Terry was born Alice Frances Taaffe in Vincennes, Indiana, on July 24, 1899. In the early 1910s she and her family moved to southern California.[1]

Career

Terry made her film debut in 1916 in Not My Sister, opposite Bessie Barriscale and William Desmond Taylor.

Terry started in films as an extra during her mid-teens, working at Thomas Ince Studio.[1] She worked for Triangle Film Corporation from 1916 to 1919.[3] For two years she worked in cutting rooms at Famous-Players-Lasky. This work helped her later when she worked with her husband.

Terry was married to Rex Ingram, a prominent director.[4] One of her biggest problems in her career was being the leading lady in movies directed by her husband. Her roles in films directed by her husband left her passive and unmemorable.[5] Ingram also hired male stars who further outshone her in The Conquering Power (1921), The Prisoner of Zenda (1922) and other films.[5] One fan magazine writer described Terry as "pliant clay" or easily manipulated on screen.

In 1924 and 1925 the marriage between Terry and Ingram was in jeopardy, and in that time period she worked under other directors. During this time period Terry worked on five movies, but her roles particularly in Any Woman (1925) and Sackcloth and Scarlet (1925), both by Paramount Pictures, proved that she was a legitimate star away from her husband.[5] When they got back together, Terry took on a more behind-the-scenes role.

Terry's work at Famous-Players-Lasky helped her in ways that were not known to the public. Ingram often became too moody to work while directing movies so Terry took over.[5] She was a competent film editor and learned how to direct from a master. When Ingram went to produce his last film, and only talkie, Baroud (1933), Terry helped so much that she was named co-director and she directed all the scenes Ingram appeared in.[2] Baroud highlighted Alice's ability as an all-around filmmaker but she never took that further.

Terry worked with Ramón Novarro, a popular a film star from Mexico who drew in audiences as a "Latin lover", and became known as a sex symbol after the death of Rudolph Valentino. Many have said that Novarro outdid Terry in many films such as The Prisoner of Zenda (1922), The Arab (1924) and others; but this didn't hinder their friendship.

Personal life

On November 5, 1921, Terry married Ingram during production of The Prisoner of Zenda (1922),[1] which he directed and in which she appeared as Princess Flavia. They sneaked away over one weekend, were married in Pasadena, and returned to work promptly the following Monday.

In 1923 Terry and Ingram decided to move to the French Riviera. They formed a small studio in Nice and made several films on location in North Africa, Spain, and Italy for MGM and others.

During the making of The Arab (1924) in Tunisia, they met a street child named Kada-Abd-el-Kader, whom they adopted upon learning that he was an orphan. Allegedly, he misrepresented his age to make himself seem younger to his adoptive parents.

Terry was known for being open minded and acted as a cover for Ramón Novarro's sexuality. In the 1930s she went with Novarro, Barry Norton, and other homosexual actors to Hollywood nightspots to act as a cover, which received backlash in the magazine The Hollywood Reporter.[5]

When Ingram decided to return to Los Angeles he asked Terry to find a home by a river. One night when Terry was drinking with friends she instructed the cab to pull over so she could throw up. When Terry was done, she looked up and saw a property in Studio City on the Los Angeles River and decided that this was the place where her new home with Rex would be.[7]

Once Terry and Ingram moved back to the United States they started having problems with their adopted son, Kada-Abd-el-Kader. He "began associating with fast women and fast cars throughout the San Fernando Valley." Terry and Ingram sent him back to Morocco "to finish school." Kada-Abd-el-Kader never went back to school, but he later became a tourist guide in Morocco and Algiers. El-Kader would always tell tourists that he was the adopted son of Ingram and Terry.

Terry and Ingram retired in the 1930s and took up painting. When Ingram died in 1950, Terry invited four of his mistresses to his funeral.[5] When she was asked how she could invite four of his mistresses to the post-funeral party said: "Who cares, I'm the only one that can call herself Mrs. Rex Ingram."[5]

After Ingram's death Terry's sister Edna moved into the property on Kelsey Street and controlled Alice's life. Alice had a lover, Gerald Fielding, who wanted to move in with her, but Edna forbade it.[5] It is speculated that Edna was jealous of Alice, Edna started as an extra as movies just like her sister, but then married a financial advisor and she stopped acting altogether.[5]

Terry was still active in the 1970s. She loved hosting Sunday afternoon parties and going out to dinner in extravagant, floor length mink coats.[5] She was proud of her appearance and wanted to make sure all other women were envious.

Death

On December 22, 1987, Terry died from Alzheimer's in a Burbank, California, hospital. Her grave is located in the Valhalla Memorial Park Cemetery in North Hollywood, Los Angeles, California.[8] For her contribution to the motion picture industry, Alice Terry has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6626 Hollywood Boulevard.[9]

Filmography

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1916 | Not My Sister | Ruth Tyler | Credited as Alice Taafe Lost film |

| Civilization | Extra (Various, from a peasant to a German Soldier) | Uncredited | |

| A Corner in Colleens | Daisy | Credited as Alice Taafe Lost film | |

| 1917 | Wild Winship's Widow | Marjory Howe | Credited as Alice Taafe Lost film |

| Strictly Business | Lost film | ||

| The Bottom of the Well | Anita Thomas | ||

| Alimony | Extra | Uncredited Lost film | |

| 1918 | The Clarion Call | Lost film | |

| A Bachelor's Children | Penelope Winthrop | Lost film | |

| Old Wives for New | Saleslady | Credited as Alice Taafe | |

| The Song and the Sergeant | Lost film | ||

| Sisters of the Golden Circle | Mrs. Pinkey McGuire | Lost film | |

| The Brief Debut of Tildy | Tildy | Lost film | |

| Love Watches | Charlotte Bernier | Lost film | |

| The Trimmed Lamp | Lost film | ||

| 1919 | Thin Ice | Jocelyn Miller | |

| The Love Burglar | Elsie Strong | Credited as Alice Taafe Lost film | |

| The Valley of the Giants | Mrs. Cardigan | Credited as Alice Taafe Alternative title: In the Valley of the Giants | |

| The Day She Paid | Credited as Alice Taafe Alternative title: Oats and the Woman Lost film | ||

| 1920 | Shore Acres | Extra | Uncredited Lost film |

| The Devil's Pass Key | Extra | Uncredited Lost film | |

| Hearts Are Trumps | Dora Woodberry | Lost film | |

| 1921 | The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse | Marguerite Laurier | |

| The Conquering Power | Eugenie Grandet | Alternative title: Eugenie Grandet | |

| 1922 | Turn To The Right | Elsie Tillinger | |

| The Prisoner of Zenda | Princess Flavia | ||

| 1923 | Where the Pavement Ends | Matilda Spener | Lost film |

| Scaramouche | Aline de Kercadiou, Quintin's Niece | ||

| 1924 | The Arab | Mary Hilbert | |

| 1925 | The Great Divide | Ruth Jordan | |

| Sackcloth and Scarlet | Joan Freeman | Lost film | |

| Confessions of a Queen | Frederika/The Queen | Incomplete film | |

| Any Woman | Ellen Linden | Lost film | |

| 1926 | Mare Nostrum | Freya Talberg | Alternative title: Our Sea |

| The Magician | Margaret Dauncey | ||

| 1927 | Lovers | Felicia | Lost film |

| The Garden of Allah | Domini Enfilden | Incomplete film | |

| 1928 | The Three Passions | Lady Victoria Burlington | |

| 1932 | Baroud | Co-director Alternative title: Love in Morocco |

References

- 1 2 3 Soares, André (April 19, 2010). Beyond Paradise: The Life of Ramon Novarro. Univ. Press of Mississippi. pp. 31–32. ISBN 978-1-60473-458-4. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ↑ "Motion Picture Classic (1921-1927)". archive.org. Brewster Publications. 1921. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- ↑ Brennan, Sandra. "Alice Terry". AllMovie. Archived from the original on June 6, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ↑ "Rex Ingram". www.tcd.ie. Archived from the original on November 2, 2019. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Slide, Anthony; Silent Topics: Essays on Undocumented Areas of Silent Film; p. 48

- ↑ "When the Five O'Clock Whistle Blows in Hollywood". Vanity Fair. September 1922. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

- ↑ Slide, Anthony (February 1, 2010). Silent Players: A Biographical and Autobiographical Study of 100 Silent Film Actors and Actresses. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0813137452.

- ↑ Ellenberger, A.R. (2001). Celebrities in Los Angeles Cemeteries: A Directory (in Spanish). McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-7864-0983-9. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- ↑ "Alice Terry". Hollywood Walk of Fame. October 25, 2019. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

External links

- Alice Terry at IMDb

- Alice Terry Archived August 12, 2019, at the Wayback Machine at the Women Film Pioneers Project

- Photographs and bibliography