| Alfonso V | |

|---|---|

Alfonso as a Knight of the Golden Fleece Miniature from the southern Netherlands, 1473 | |

| King of Aragon | |

| Reign | 2 April 1416 – 27 June 1458 |

| Predecessor | Ferdinand I |

| Successor | John II |

| King of Naples | |

| Reign | 2 June 1442 – 27 June 1458 |

| Predecessor | René |

| Successor | Ferdinand I |

| Born | 1396 Medina del Campo, Kingdom of Castile |

| Died | 27 June 1458 (aged 61–62) Castel dell'Ovo, Naples, Kingdom of Naples |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | |

| Issue among others... | Ferdinand I of Naples |

| House | Trastámara |

| Father | Ferdinand I of Aragon |

| Mother | Eleanor of Alburquerque |

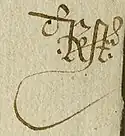

| Signature |  |

Alfonso the Magnanimous (Alfons el Magnànim in Catalan)[lower-alpha 1] (1396 – 27 June 1458) was King of Aragon and King of Sicily (as Alfonso V) and the ruler of the Crown of Aragon[lower-alpha 2] from 1416 and King of Naples (as Alfonso I) from 1442 until his death. He was involved with struggles to the throne of the Kingdom of Naples with Louis III of Anjou, Joanna II of Naples and their supporters, but ultimately failed and lost Naples in 1424. He recaptured it in 1442 and was crowned king of Naples. He had good relations with his vassal, Stjepan Kosača, and his ally, Skanderbeg, providing assistance in their struggles in the Balkans. He led diplomatic contacts with the Ethiopian Empire and was a prominent political figure of the early Renaissance, being a supporter of literature as well as commissioning several constructions for the Castel Nuovo.

Early life

Born at Medina del Campo, he was the son of Ferdinand of Trastámara and Eleanor of Alburquerque. Ferdinand was the brother of King Henry III of Castile, and Alfonso was betrothed to his uncle King Henry's daughter Maria in 1408. In 1412, Ferdinand was selected to succeed to the territories of the Crown of Aragon. Alfonso and Maria's marriage was celebrated in Valencia on 12 June 1415.

King Ferdinand died on 2 April 1416, and Alfonso succeeded him as king of Aragon, Valencia, and Majorca and count of Barcelona. He also claimed the island of Sardinia, though it was then in the possession of Genoa. Alfonso was also in possession of much of Corsica by the 1420s.[1]

Alfonso's marriage with Maria was childless. His mistress Lucrezia d'Alagno served as a de facto queen at the Neapolitan court as well as an inspiring muse. With another mistress, Giraldona Carlino, Alfonso had three children: Ferdinand (1423–1494), Maria (who married Leonello d'Este), and Eleanor (who married Mariano Marzano).[2] With the last mistress Ippolita, married de'Giudici, Alfonso had one daughther Colia (1430-1473/5) married in 1445 with Emanuele d'Appiano, Lord of Piombino, Count of Holy Roman Empire. The d'Appiano d'Aragona family receive, in 1509 the title of Prince of Holy Roman Empire.

Alfonso was the object of diplomatic contacts from the Empire of Ethiopia. In 1428, he received a letter from Yeshaq I of Ethiopia, borne by two dignitaries, which proposed an alliance against the Muslims and would be sealed by a dual marriage that would require Alfonso's brother Peter to bring a group of artisans to Ethiopia where he would marry Yeshaq's daughter.[3] In return, Alfonso sent a party of 13 craftsmen, all of whom perished on the way to Ethiopia.[4] He later sent a letter to Yeshaq's successor Zara Yaqob in 1450, in which he wrote that he would be happy to send artisans to Ethiopia if their safe arrival could be guaranteed, but it probably never reached Zara Yaqob.[5][6]

Struggle for Naples

In 1421 the childless Queen Joanna II of Naples adopted and named him as heir to the Kingdom of Naples, and Alfonso went to Naples.[7] Here he hired the condottiero Braccio da Montone with the task of reducing the resistance of his rival claimant, Louis III of Anjou, and his forces led by Muzio Attendolo Sforza. With Pope Martin V supporting Sforza, Alfonso switched his religious allegiance to the Aragonese antipope Benedict XIII. When Sforza abandoned Louis' cause, Alfonso seemed to have all his problems solved; however, his relationship with Joanna suddenly worsened, and in May 1423 he had her lover, Gianni Caracciolo, a powerful figure in the Neapolitan court, arrested.[7]

After an attempt to arrest the queen herself had failed, Joan called on Sforza who defeated the Aragonese militias near Castel Capuano in Naples. Alfonso fled to Castel Nuovo, but the help of a fleet of 22 galleys led by Giovanni da Cardona improved his situation.[8] Sforza and Joanna ransomed Caracciolo and retreated to the fortress of Aversa.[8] Here she repudiated her earlier adoption of Alfonso and, with the backing of Martin V, named Louis III as her heir instead.[9]

The duke of Milan, Filippo Maria Visconti, joined the anti-Aragonese coalition. Alfonso requested support from Braccio da Montone, who was besieging Joanna's troops in L'Aquila, but had to set sail for Spain, where a war had broken out between his brothers and the Kingdom of Castile. On his way towards Barcelona, Alfonso sacked Marseille, a possession of Louis III.[8]

In late 1423 the Genoese fleet of Filippo Maria Visconti moved in the southern Tyrrhenian Sea, rapidly conquering Gaeta, Procida, Castellammare and Sorrento. Naples, which was held by Alfonso's brother, Pedro de Aragon,[8] was besieged in 1424 by the Genoese ships and Joanna's troops, now led by Francesco Sforza, the son of Muzio Sforza (who had met his death at L'Aquila). The city fell in April 1424. Pedro, after a short resistance in Castel Nuovo, fled to Sicily in August. Joanna II and Louis III again took possession of the realm, although the true power was in the hands of Gianni Caracciolo.[8]

An opportunity for Alfonso to reconquer Naples occurred in 1432, when Caracciolo was killed in a conspiracy.[8] Alfonso tried to regain the favour of the queen, but failed, and had to wait for the death of both Louis (at Cosenza in 1434) and Joanna herself (February 1435). In her will, she bequeathed her realm to René of Anjou, Louis III's younger brother. This solution was opposed by the new pope, Eugene IV, who was the feudal overlord of the Kingdom of Naples. The Neapolitans having called in the French, Alfonso decided to intervene and, with the support of several barons of the kingdom, captured Capua and besieged the important sea fortress of Gaeta. His fleet of 25 galleys was met by the Genoese ships sent by Visconti, led by Biagio Assereto. In the Battle of Ponza that ensued, Alfonso was defeated and taken prisoner.[10]

In Milan, Alfonso impressed his captor with his cultured demeanor and persuaded him to let him go by persuading that it was not in Milan's interest to prevent the victory of the Aragonese party in Naples.[10] Helped by a Sicilian fleet, Alfonso recaptured Capua and set his base in Gaeta in February 1436. Meanwhile, papal troops had invaded the Neapolitan kingdom, but Alfonso bribed their commander, Cardinal Giovanni Vitelleschi, and their successes waned.[11]

In the meantime, René had managed to reach Naples on 19 May 1438. Alfonso tried to besiege the city in the following September, but failed.[10] His brother Pedro was killed during the battle. Castel Nuovo, where an Aragonese garrison resisted, fell to the Angevine mercenaries in August 1439. After the death of his condottiero Jacopo Caldora, however, René's fortune started to decline: Alfonso could easily capture Aversa, Salerno, Benevento, Manfredonia and Bitonto. René, whose possession included now only part of the Abruzzi and Naples, obtained 10,000 men from the pope, but the cardinal leading them signed a truce with Alfonso. Giovanni Sforza came with a reduced corps, as troops sent by Eugene IV had halted his father Francesco in the Marche.

Alfonso, provided with the most impressive artillery of the times, again besieged Naples. The siege began on 10 November 1441, ending on 2 June the following year.[12] After the return of René to Provence, Alfonso easily reduced the remaining resistance and made his triumphal entrance in Naples on 26 February 1443, as the monarch of a pacified kingdom.[10]

Alfonso then reunited under his dominion the kingdoms of Naples and Sicily, divided since the Sicilian Vespers. After the personal union, he began to call himself Rex Utriusque Siciliae; this was then used by other kings and his successors who ruled over those territories.

Art and administration

Like many Renaissance rulers, Alfonso V was a patron of the arts. He founded the Academy of Naples under Giovanni Pontano, and for his entrance into the city in 1443 had a magnificent triumphal arch added to the main gate of Castel Nuovo.[13] Alfonso V supplied the theme of Renaissance sculptures over the west entrance.

Alfonso was particularly attracted to classical literature. He reportedly brought copies of the works of Livy and Julius Caesar on his campaigns; the poet Antonio Beccadelli even claimed that Alfonso was cured of a disease by the reading of a few pages from Quintus Curtius Rufus' history of Alexander the Great. Although this reputed erudition attracted scholars to his court, Alfonso apparently enjoyed pitting them against each other in spectacles of bawdy Latin rhetoric.[14]

After his conquest of Naples in 1442, Alfonso ruled primarily through his mercenaries and political lackeys. In his Italian kingdom, he maintained the former political and administrative institutions. His holdings in Spain were governed by his wife Maria.[15]

A unified General Chancellorship for the whole Aragonese realm was set up in Naples, although the main functionaries were of Aragonese nationality. Apart from financial, administrative and artistic improvements, his other accomplishments in the Sicilian kingdom include the restoration of the aqueducts, the drainage of marshy areas, and the paving of streets.[16]

Alfonso founded the first university of Sicily, the Siciliae Studium Generale.

Later life

Alfonso was also a powerful and faithful supporter of Skanderbeg, whom he decided to take under his protection as a vassal in 1451, shortly after the latter had scored his second victory against Murad II. In addition to financial assistance, he supplied the Albanian leader with troops, military equipment, and sanctuary for himself and his family if such a need should arise. This was because in 1448, while Skanderbeg was fighting off the Turkish invasions, three military columns, commanded by Demetrio Reres along with his sons Giorgio and Basilio, had been dispatched to help Alfonso V defeat the barons of Naples who had rebelled against him.[17]

He also supported Bosnian duke, Stjepan Vukčić Kosača, who turned to the king for help in his affairs in Bosnia. Alfonso made him "Knight of the Virgin", but did not provide any troops. On 15 February 1444, Stjepan signed a treaty with the king of Aragon and Naples, becoming his vassal in exchange for Alfonso's help against his enemies—Stephen Thomas and Ivaniš Pavlović (1441–1450) of the Pavlović noble family as well as the Republic of Venice.[18] In the same treaty, Stjepan promised to pay Alfonso regular tribute instead of paying the Ottoman sultan as he had done until then.[19]

Alfonso, by formally submitting his reign to the Papacy, obtained the consent of Pope Eugene IV that the Kingdom of Naples would go to his illegitimate son, Ferdinand. He died in Castel dell'Ovo in 1458, while he was planning the conquest of Genoa. At the time, Alfonso was at odds with Pope Callixtus III, who died shortly afterwards. Alfonso's Iberian possessions had been ruled for him by his brother, who succeeded him as John II of Aragon.[15] Sicily and Sardinia were also inherited by John II.

Marriage and issue

Alfonso had been betrothed to Maria of Castile (1401–1458; sister of John II of Castile) in Valladolid in 1408; the marriage was celebrated in Valencia on 12 June 1415. They failed to produce children. Alfonso had been in love with a woman of noble family named Lucrezia d'Alagno, who served as a de facto queen at the Neapolitan court as well as an inspiring muse.

Genealogical records in the Old Occitan Chronicle of Montpellier in Le petit Thalamus de Montpellier indicate that Alphonso's relationship with his mistress, Giraldona Carlino (daughter of Enrique Carlino and his wife, Isabel), produced three children:[2]

- His successor in Naples, King Ferdinand I of Naples, (born 1423; reigned 1458–1494).

- Maria d'Aragon (1425–1449) (died 1449, aged around 15 or 16). She had married in 1444 Leonello d'Este, deceased 1450.

- Leonora d'Aragona, who married c. 1443, Mariano Marzano, Duke of Squillace, Prince of Rossano. Her daughter Francesca married Leonardo III Tocco.

Notes

References

- ↑ Gallinari, Luciano (2019). "The Catalans in Sardinia and the transformation of Sardinians into a political minority in the twelfth to the fifteenth centuries". Journal of Medieval History. 45 (3): 347–359. doi:10.1080/03044181.2019.1612194. S2CID 159420253.

- 1 2 Widmayer 2006, p. 231.

- ↑ GARRETSON, PETER P. (1993). "A Note on Relations Between Ethiopia and the Kingdom of Aragon in the Fifteenth Century". Rassegna di Studi Etiopici. 37: 37–44. ISSN 0390-0096. JSTOR 41299786.

- ↑ Girma Beshah and Merid Wolde Aregay, The Question of the Union of the Churches in Luso-Ethiopian Relations (1500–1632) (Lisbon: Junta de Investigações do Ultramar and Centro de Estudos Históricos Ultramarinos, 1964), pp.13–4.

- ↑ Girma Beshah and Merid Wolde Aregay, The Question of the Union of the Churches, pp.14.

- ↑ O. G. S. Crawford (editor), Ethiopian Itineraries, circa 1400 – 1524 (Cambridge: the Hakluyt Society, 1958), pp. 12f.

- 1 2 Armstrong 1964, p. 164.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Armstrong 1964, p. 165.

- ↑ Grierson & Travaini 1998, p. 245.

- 1 2 3 4 Bisson 1991, p. 144.

- ↑ Gregorovius, Ferdinand (1859). History of the City of Rome in the Middle Ages.

- ↑ "Alfonso V | king of Aragon and Naples | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ↑ "Naples | History & Points of Interest". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ↑ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 736.

- 1 2 Bisson 1991, p. 147.

- ↑ "Alfonso V of Aragon (the Magnanimous) (1396–1458) - Dictionary definition of Alfonso V of Aragon (the Magnanimous) (1396–1458) | Encyclopedia.com: FREE online dictionary". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ↑ "The Case of the Ruthless Ruler With a Deadly Disease". Medscape. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ↑ Ćirković 1964, p. 288: Chapter 6: Učvršćivanje kraljevske vlasti (1422–1454); Part 7: Obnavljanje sistema ravnoteže snaga

- ↑ Spremić 2005, pp. 355–358.

Sources

- Armstrong, Edward (1964). "The Papacy and Naples in the Fifteenth Century". In Previte-Orton, C.W.; Brooke, Z.N. (eds.). The Cambridge Medieval History: The Close of the Middle Ages. Vol. VIII. Cambridge at the University Press.

- Ćirković, Sima (1964). Историја средњовековне босанске државе [History of the medieval Bosnian state] (in Serbian). Srpska književna zadruga.

- Bisson, T.N. (1991). The Medieval Crown of Aragon. Oxford University Press.

- Grierson, Philip; Travaini, Lucia (1998). Medieval European Coinage: Volume 14, South Italy, Sicily, Sardinia. Cambridge University Press.

- Widmayer, Jeffrey S. (2006). "The Chronicle of Montpellier H119: Text, Translation and Commentary". In Kooper, Erik (ed.). The Medieval Chronicle IV. Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-2088-7.

- Spremić, Momčilo (2005). Balkanski vazali kralja Alfonsa Aragonskog [Balkan vassals of King Alfonso of Aragon]. Beograd: Prekinut uspon.

Further reading

- O'Callaghan, Joseph F. (1975). A History of Medieval Spain. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. pp. 549–577. ISBN 0-8014-0880-6. OCLC 1272494.

- Ryder, Alan (1976). The Kingdom of Naples Under Alfonso the Magnanimous: The Making of a Modern State. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822535-5. OCLC 2704031.

- Ryder, Alan (2003). "Alfonso V, King of Aragon, The Magnanimous". In Gerli, E. Michael (ed.). Medieval Iberia : an encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-93918-6. OCLC 50404104.

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)