| Petronilla | |

|---|---|

| |

| Queen of Aragon | |

| Reign | 13 November 1137 – 18 July 1164 |

| Predecessor | Ramiro II |

| Successor | Alfonso II |

| Countess consort of Barcelona | |

| Tenure | 1150 – 1162 |

| Countess of Barcelona | |

| Reign | 1162 – 1164 |

| Predecessor | Ramon Berenguer IV |

| Successor | Alfonso II of Aragon |

| Regent of Aragon | |

| Regency | 1164 – 1173 |

| Monarch | Alfonso II |

| Born | 29 June 1136 Huesca |

| Died | 15 October 1173 (aged 37) Barcelona |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Ramon Berenguer IV, Count of Barcelona |

| Issue | |

| House | Jiménez |

| Father | Ramiro II of Aragon |

| Mother | Agnes of Aquitaine |

| Signature |  |

Petronilla (29 June[1]/11 August[2] 1136 – 15 October 1173), whose name is also spelled Petronila or Petronella (Aragonese: Peyronela or Payronella,[3] and Catalan: Peronella), was Queen of Aragon (1137–1164[4]) from the abdication of her father, Ramiro II, in 1137 until her own abdication in 1164. After her abdication she acted as regent during the minority of her son (1164–1173). She was the last ruling member of the Jiménez dynasty in Aragon, and by marriage brought the throne to the House of Barcelona.

Early life

Born in August 1136, Petronilla was the daughter of Ramiro II of Aragon and Agnes of Aquitaine.[5] She came to the throne through special circumstances. Her father, Ramiro, was bishop of Barbastro-Roda when his brother, Alfonso I, died childless in 1134. Alfonso left the kingdom to the Knights Templar, the Hospitallers, and the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre, but his decision was not respected.[5] The aristocracy of Navarre elected a king of their own, restoring their independence, and the nobility of Aragon raised Ramiro to the throne.[5] Pope Innocent II rejected this election, seeking to affirm Alfonso I's final will.[5] Despite the lack of papal approval, King Ramiro the Monk, as he is known, married Agnes of Aquitaine in 1135.[5]

Petronilla's marriage was a very important matter of state. The nobility had rejected the proposition of Alfonso VII of Castile to arrange a marriage between Petronilla and his son Sancho and to educate her at his court. When she was just a little over one year old, Petronilla was betrothed in Barbastro on 11 August 1137 to Raymond Berengar IV, Count of Barcelona, who was twenty-three years her senior.[6]

Queen regnant

At El Castellar on 13 November 1137, Ramiro abdicated, transferred authority to Ramon Berenguer, and returned to monastic life.[6] Ramon Berenger de facto ruled the kingdom using the title of "Prince of the Aragonese" (princeps Aragonensis).

In August 1150, when Petronilla was fourteen, the betrothal was ratified at a wedding ceremony held in the city of Lleida.[7] Petronilla consummated her marriage to Ramon Berenguer in the early part of 1151, when she reached the age of 15. The marriage produced five children: Peter (1152–57), Raymond Berengar (1157–96), Peter (1158–81), Dulce (1160–98), and Sancho (1161–1223). While she was pregnant with the first, on 4 April 1152, she wrote up a will bequeathing her kingdom to her husband in case she did not survive childbirth.[8] Even before the death of her father Ramiro II, Petronilla was using the title Queen of Aragon in her will, written in 1152.[9]

While her husband was away in Provence (1156–57), where he was regent (since 1144) for the young Count Raymond Berengar II, Queen Petronilla remained in Barcelona. Accounting records show her moving between there and Vilamajor and Sant Celoni while presiding over the court in Raymond Berengar's absence.[10]

After her husband's death in 1162, Petronilla received the prosperous County of Besalú and the Vall de Ribes for life. As a widow, she was the only ruler of Aragon for the next two years.

Regent

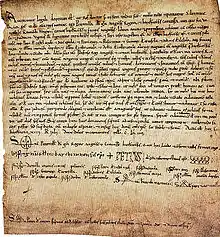

Even after the death of her husband Ramon Berenguer IV, the titles of Petronilla were Queen of Aragon and Countess of Barcelona in the document about her abdication in 1164.[11] Her eldest son was seven years old when, on 18 June 1164 (Actum est hoc in Barchinona XIIII kalendas julii anno Dominice incarnationis M C LXIIII), Petronilla abdicated the throne of Aragon and passed it to him. When Raymond Berenguer inherited the throne from his mother, he changed his name to Alfonso out of deference to the Aragonese. The second son, named Peter, then changed his name to Raymond Berenguer. Her son and heir was only seven years old when she abdicated in his favor, and so she continued to rule after her abdication, this time acting as his regent during his minority.

Petronilla died in Barcelona in October 1173 and was buried at Barcelona Cathedral; her tomb has been lost. After her death, Besalú and Vall de Ribes reverted to the direct domain of the count of Barcelona, her son Alfonso, who by 1174 had bestowed Besalú on his wife, Sancha.[12] In the Ribes, the local bailiff, Ramon, had carved out for himself "a virtually independent administrative authority" there. He had conducted an inventory for Petronilla after Raymond Berenguer's death, and his son and namesake was in power in 1198.[13]

Legacy

In 1410, after the death of King Martin without living legitimate descendants, the House of Barcelona became extinct in the legitimate male line. Two years later, Ferdinand I was enthroned per the Compromise of Caspe. Although Ferdinand triumphed mainly for political and military reasons, the theoretical basis of his candidacy was inheritance in the female line, for which Queen Petronilla served as the precedent. He was Martin's closest legitimate male relative, but related through a woman. His chief opponent, Count James II of Urgell, was related to Martin more distantly, but in the male line. In Catalonia there were indications that women were forbidden to hold comital office, but in Aragon there was no legislation on the subject. In both places there were a few cases of women who had passed on their right to their sons, most importantly Petronilla.

There is a long debate whether Petronilla was the true ruler of Aragon. Some claim that Ramiro II gave the kingdom of Aragon to his son-in-law and that the presence of Petronilla was secondary. According to Jerónimo de Zurita, there was a clause in the pact with Ramon Berenguer stating that if Petronilla died, Aragon would pass to the children of Ramon Berenguer through a future second marriage. In any case, there is insufficient documentation to make a completely conclusive statement about the question and the Compromise of Caspe confirmed the legitimacy of female transmission.[14]

References

- ↑ "Gran Enciclopedia Aragonesa". Archived from the original on 2016-03-06. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ Antonio Ubieto Arteta (1987), Historia de Aragón: creación y desarrollo de la corona de Aragón (Zaragoza: Anubar), p. 131.

- ↑ Ana Isabel Lapeña Paúl (2008): "Apéndice III. Ramiro II en la Crónica de San Juan de la Peña". Ramiro II de Aragón: el rey monje (1134–1137). Gijón: Trea. p. 298. ISBN 978-84-9704-392-2

- ↑ Tomás Ximénez de Embún y Val [in Spanish] (1878). Ensayo histórico acerca de los orígenes de Aragón y Navarra (in Spanish). Impr. del Hospicio. p. 258.

Doña Petronila, 1137-1164.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Waag 2022, p. 97.

- 1 2 Reilly 1998, p. 61.

- ↑ Reilly 1998, p. 109.

- ↑ Reilly 1998, p. 118.

- ↑ Colección de documentos inéditos del Archivo General de la Corona de Aragón. Vol. 4. J.E. Montfort. 1848. p. 202.

Ad cunctorum noticiam volumus pervenire quoniam ego Peronella regina aragonensis jacens et in partu laborans apud Barchinonam.

- ↑ Bisson 1984, p. 50.

- ↑ Colección de documentos inéditos del Archivo General de la Corona de Aragón. Vol. 4. J.E. Montfort. 1848. p. 391.

Quapropter in Dei eterni regis nomine ego Petronilla Dei gratia aragonensis regina et barchinonensis comitissa

- ↑ Bisson 1984, p. 179.

- ↑ Bisson 1984, p. 185.

- ↑ Cristina Segura Graió, "Derechos sucesorios al trono de las mujeres en la Corona de Aragón" Mayurqa 22 (1989): 591–99.

Sources

- Bisson, T. N. (1984). Fiscal Accounts of Catalonia under the Early Count-Kings (1151–1213). University of California Press.

- Bisson, Thomas N. The Medieval Crown of Aragon: A Short History. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2000.

- Chaytor, Henry John. A History of Aragon and Catalonia. London: Methuan, 1933.

- Hirel-Wouts, Sophie. "Cuando abdica la reina... Reflexiones sobre el papel pacificador de Petronila, reina de Aragón y condesa de Barcelona (siglo XIII)", e-Spania, vol. 20 (2015), retrieved 8 June 2016.

- Reilly, B. F. (1998). The Kingdom of León-Castilla Under King Alfonso VII, 1126–1157. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Stalls, William C. "Queenship and the Royal Patrimony in Twelfth-Century Iberia: The Example of Petronilla of Aragon", Queens, Regents and Potentates, Women of Power, vol. 1 (Boydell & Brewer, 1995), 49–61.

- Waag, Anaïs (2022). Church, Stephen D. (ed.). "Rulership, Authority, and Power in the Middle Ages: The Proprietary Queen as Head of Dynasty". Anglo-Norman Studies XLIV: Proceedings of the Battle Conference 2021. The Boydell Press: 71–104.

External links

Media related to Petronila of Aragon at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Petronila of Aragon at Wikimedia Commons

.svg.png.webp)