The Alpine Fortress (German: Alpenfestung) or Alpine Redoubt was the World War II German national redoubt planned by Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler in November and December 1943.[lower-alpha 1] Plans envisaged Germany's government and armed forces retreating to an area from "southern Bavaria across western Austria to northern Italy".[lower-alpha 2] The scheme was never fully endorsed by Hitler, and no serious attempt was made to put it into operation, although the concept served as an effective tool of propaganda and military deception carried out by the Germans in the final stages of the war. After surrendering to the Americans, the Wehrmacht General Kurt Dittmar told them that the redoubt never existed.

History

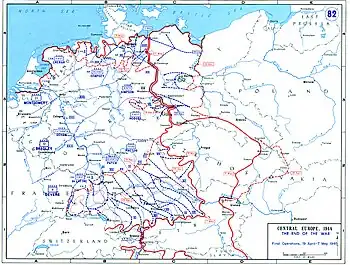

In the six months following the D-Day landings in Normandy in June 1944, the American, British, and French armies advanced to the Rhine and seemed poised to strike into the heart of Germany, while the Soviet Red Army, advancing from the east through Poland, reached the Oder. It seemed likely that the Allies would soon take Berlin and overrun all of the North German Plain. In these circumstances, it occurred both to some leading figures in the German régime and to the Allies that the logical step for the Germans to take would be to move their government to the mountainous areas of southern Germany and Austria, where a relatively small number of determined troops could hold out for some time.

A number of intelligence reports to the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Forces (SHAEF) identified the Alpine area as having stores of foodstuffs and military supplies built up over the preceding six months, and even as harbouring armaments-production facilities. Within this fortified terrain, according to the reports, Hitler would be able to evade the Allies and cause tremendous difficulties for occupying Allied forces throughout Germany.

In January 1945 the Nazi minister of propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, set up a special unit to invent and spread rumours about an Alpenfestung.[1] Goebbels also leaked rumours to neutral governments,[2] thus keeping the Redoubt myth alive and the Redoubt's state of readiness unclear. He enlisted the assistance of the SS intelligence service (the SD) to produce faked blueprints and reports on construction supplies, armament production and troop transfers to the Redoubt.[3] This utter deception of Allied military intelligence is considered to be one of the greatest feats of the German Abwehr (abolished in February 1944) during the entire war.

Although Adolf Hitler never fully endorsed the Alpenfestung plan, he did provisionally agree to it at a conference with Franz Hofer (the Gauleiter of Tirol-Vorarlberg) in January 1945.[4] Hitler also issued an order on 24 April 1945 for the evacuation of remaining government personnel from Berlin to the Redoubt. He made it clear that he would not leave Berlin himself, even if it were to fall to the Soviets, as it did on 2 May 1945.

Nevertheless, the myth of the Germans' National Redoubt had serious military and political consequences. Once the Anglo-American armies had crossed the Rhine and advanced into Western Germany, strategists had to make decisions: whether to advance on a narrow front towards Berlin or in a simultaneous push by all Western armies spanning from the North Sea to the Alps. America's most aggressive commander, Third Army head General George S. Patton in General Omar Bradley's centrally located Twelfth Army Group, had advocated a narrow front ever since D-Day, and did so again; likewise at this point British 21st Army Group chief Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery in the north, each lobbying to command the decisive spearhead. Cautious Allied commander-in-chief U.S. General Dwight Eisenhower, however, resisted both Bradley's and Montgomery's proposals. Ultimately, the broad front strategy left the Seventh Army of General Jacob L. Devers' southern Sixth Army Group in a position at war's end to race south through Bavaria into Austria to prevent any German entrenchment in a mountain redoubt and to cut off alpine passes to Nazi escape.

When the American armies penetrated Bavaria and western Austria at the end of April 1945, they met little organized resistance, and revealed the "National Redoubt" concept as a myth.[5] The alleged Alpine Fortress was one of three reasons associated with SHAEF's movement of forces towards southern Germany rather than towards Berlin, the other two being that plans had assigned the city to the proposed Soviet Zone of Occupation, and that any battle for Berlin might have entailed unacceptably high Western Allied casualties.

Evacuations to the Alpine Fortress

- In February/early March 1945, SHAEF received reports that German military, government and Nazi Party offices and their staffs were leaving Berlin for the area around Berchtesgaden, the site of Hitler's retreat in the Bavarian Alps.

- In February 1945, the SS evacuated V-2 rocket scientists from the Peenemünde Army Research Center to the Alpine Fortress.

- SS Generalleutnant Gottlob Berger claimed that Hitler had signed a 22 April 1945 order to evacuate 35,000 prisoners to the Alpine Fortress as hostages, but Berger did not carry out the order[6] (many evacuated locations also failed to obey Hitler's order requiring Demolitions on Reich Territory, e.g., Mittelwerk).

Post-war claims

Post-war claims regarding the Alpine Fortress include:

- The Alpine Fortress "grew into so exaggerated a scheme that I am astonished we could have believed it as innocently as we did. But while it persisted, this legend of the Redoubt was too ominous a threat to be ignored." (General Omar Bradley)[7][8]

- One Allied assessment of the Alpine Fortress "must rank as one of the worst intelligence reports of all time, but no one knew that in March of 1945, and few even suspected it". (author Stephen E. Ambrose)[9]

See also

References

Explanatory notes

- ↑ "Himmler started laying the plans for underground warfare in the last two months of 1943.... The plans are threefold, embracing (1) Open warfare directed from Hitler's mountain headquarters; (2) Sabotage and guerrilla activity conducted by partisan bands organized by districts, and (3) Propaganda warfare to be carried on by some 200,000 Nazi followers in Europe and elsewhere. Strongholds Established Already picked S.S. (elite) troops have been established in underground strongholds and hospitals in the Austrian, Bavarian and Italian Alpine area and it is the plan of Nazi leaders to flee to that region when the German military collapse comes." Gallagher, Wes (13 December 1944). "Nazis Prepared for Five Years Underground Warfare". Evening Independent. St. Petersburg, Florida. Associated Press. Retrieved 4 February 2018..

- ↑ "But what of the top Nazis who cannot hide? With a compact army of young SS and Hitler Youth fanatics, they will retreat, behind a loyal rearguard cover of Volksgrenadiere and Volksstürmer, to the Alpine massif which reaches from southern Bavaria across western Austria to northern Italy. There immense stores of food and munitions are being laid down in prepared fortifications. If the retreat is a success, such an army might hold out for years." ("World Battlefronts: Battle of Germany: The Man Who Can't Surrender". Time. 12 February 1945. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012.)

Citations

- ↑

Fritz, Stephen G. (8 October 2004). "Waiting for the End". Endkampf: Soldiers, Civilians, and the Death of the Third Reich. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. p. 6. ISBN 9780813171906. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

Only Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels recognized the value of an Alpenfestung, and then merely to exploit 'redoubt hysteria' among the Americans. Convening a secret meeting of German editors and journalists in early December 1944, Goebbels ensured the dissemination of rumors about a national redoubt by expressly forbidding any mention of such a thing in German newspapers. Then, in January 1945, he organized a special propaganda section to concoct stories about Alpine defensive positions. All the stories were to stress the same themes: impregnable fortifications, vast underground storehouses loaded with supplies, subterranean factories, and elite troops willing to fight fanatically to the last.

- ↑

Fritz, Stephen G. (8 October 2004). "Waiting for the End". Endkampf: Soldiers, Civilians, and the Death of the Third Reich. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. p. 6. ISBN 9780813171906. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

In addition, Goebbels saw to it that rumors leaked not only to neutral governments but also to German troops. Because Allied intelligence drew on POW interrogations as well as reports from neutral countries, these actions ensured the further dissemination of apparent evidence of an Alpenfestung.

- ↑

Compare:

Fritz, Stephen G. (8 October 2004). "Waiting for the End". Endkampf: Soldiers, Civilians, and the Death of the Third Reich. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. p. 6. ISBN 9780813171906. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

Finally, Goebbels enlisted the aid of the SD to produce fake blueprints, reports on construction timetables, and plans for future transfers of troops and ammunition into the redoubt.

- ↑ "Ultra and the Myth of the National Redoubt by Marvin Meek". www.allworldwars.com. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ↑ Headquarters, European Theater of Operations (15 April 1945). "World War II Operational Documents". pp. 382–383. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ↑ Nichol, John; Rennell, Tony (2002). "The Last Escape". Penguin UK. Archived from the original on 20 February 2014. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ↑ Bradley, Omar N. (4 May 1999). A Soldier's Story. Holt Publishing. p. 536. ISBN 0-375-75421-0.

- ↑ Shirer, William L. (15 November 1990). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany. Simon & Schuster. pp. 1106–. ISBN 978-0-671-72868-7.

- ↑

Ambrose, Stephen E (1999) [1970]. "19: Crossing the Rhine and a change in plan". The Supreme Commander: The War Years of General Dwight D. Eisenhower (reprint ed.). Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. p. 624. ISBN 9781578062065. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

This must rank as one of the worst intelligence reports of all time, but no one knew that in March of 1945, and few even suspected it. [...] Even Churchill was afraid of these possible developments.

External links

- United States Army in World War II, European Theater of Operations: The Last Offensive (Washington, D.C. 1973): Chapter XVIII: "The Myth of the Redoubt"