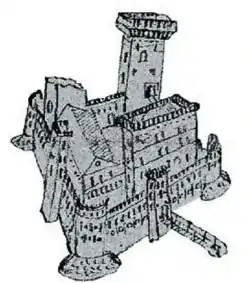

| Altamura castle | |

|---|---|

Castello di Altamura | |

| Altamura, Apulia, Italy in Italy | |

Altamura Castle (late 16th century)[1] | |

| Coordinates | 40°49′44″N 16°33′7″E / 40.82889°N 16.55194°E |

| Length | 67mx55m |

| Site information | |

| Open to the public | No |

| Condition | completely demolished |

| Site history | |

| Built | 11th-13th century |

| Built by | Norman (uncertain), Frederick II of the Holy Roman Empire |

| Garrison information | |

| Past commanders | Giovanni Antonio Del Balzo Orsini |

Altamura Castle (Italian: Castello di Altamura) was a castle located in the city of Altamura, now completely demolished. It was located over today's piazza Matteotti and a few remains of it are still visible inside the adjacent buildings, which were built partly with stones and structural elements from the castle. In a warehouse are an ogival arch and some stone coats of arms. A few other remains are found in the adjacent buildings, which were built in the 19th century.[2]

The square on which stood the castle was previously named piazza Castello (which means 'Castle square').[2] In Altamura dialect, the square is called u cuastidde (/u kwa'stɪdːᵊ/), which means 'the castle'.

History

The castle was probably built before Altamura was founded by king Frederick II (1243) and it was probably the seat of the feudal lord governing the nearby cluster of villages. Those villages were then displaced into the city right after the city was founded (1243). The proof that the castle was built before lies in some remains of the castle, that were visible until the demolition; Domenico Santoro (1688) wrote that there were insignia of Norman kings near the windows of the castle's church.[3] The castle was for a long time home to the Altamura family – the descendants of Sparano da Bari) – and it was the favorite residence of Giovanni Antonio Orsini Del Balzo, who was murdered therein in 1463.[4]

It also served as a prison. According to Cesare Orlandi, it is particularly well known for the imprisonment of prince Otto IV, husband to queen Joanna I of Naples.[5] According to Orlandi, Corrado Corradino was also imprisoned therein.[6]

At the battlements of Altamura castle, in December 1357, the rebel Giovanni Pipino di Altamura was also hanged, sitting on a female donkey and wearing a paper crown, for having rebelled against the king and for calling himself "king of Apulia".[7] His body was ripped into four parts, which were then exhibited in different parts of the city of Altamura as a warning for disobedience. His thigh, in particular, was exposed on top of the city walls, more precisely on the right of Porta Matera where, in memory of this, a bas-relief depicting the "thigh of Pipino" was made and placed. In 1648, the bas-relief was destroyed and rebuilt following the restoration of the city walls.[8]

The castle was abandoned in the late 15th century;[4] thereafter it slowly started to fall into pieces, so much that in 1642 it was already "uninhabitable and apparently likely to collapse".[9] The demolition date is not known, though it seems reasonable that it might have been demolished in the 19th century, as the castle occurs in many 18th century drawings.[10]

In the 20th century, part of the foundations appeared during construction work on the square. However, the remains found were destroyed and not even a sketch of the foundations was drawn up.[2]

Structure and dimensions

The castle was located close to the city's medieval walls. Domenico Santoro (1688) mentioned a courtyard and church inside the castle. On the 18th century drawings and paintings are visible four big corner towers (consistently with other castles commissioned by Frederick II). In circa 1330, a new big circular tower was added right next to the city walls.[4]

The structure of the castle is likely to have been modified and adapted to the needs. A part of the structure built by the Norman kings may have been incorporated in the renovation works made by Frederick II on the occasion of the foundation of Altamura.[4]

Circa 1330, according to Domenico Santoro (1688), King Robert of Anjou added a tower, called a fake tower, on which the coat of arms of the Anjou family was visible.[11] Domenico Santoro stated that a proof of this was of the coat of arms of Robert of Anjou. However, local historian Giuseppe Pupillo hypothesized that Domenico Santoro may have confused the coats of arms.

One of the coats of arms found in the buildings close to the area of the castle (the only remains of the castle) is a coat of arms similar to that of Robert of Anjou, but it is not the same. It is the coat of arms of Louis I of Naples. The same coat of arms occurs on the portal Altamura Cathedral (together with that of Joanna I of Naples.)[12] Because of this, historian Giuseppe Pupillo stated that attributing the "fake tower" to Robert of Anjou is quite acceptable, but there is not enough evidence to confirm the other statement provided by Domenico Santoro, according to which the coat of arms on the "false tower" belonged to Robert of Anjou. [13]

Details about the dimensions are given mainly by a plan sketch drawn up by architect Donato Giannuzzi in the mid-18th century. The ground dimensions were 67 meters by 55 meters, while the internal courtyard was 38 meters long and 25 meters wide. The whole castle stretched up to today's via Santa Teresa, farther than the square itself.[14]

It is worth to note that Castel del Monte was first called by that name in a decree from Ferdinand I of Naples, written inside Altamura Castle on December 1, 1463. Castel del Monte was previously called Castello di Santa Maria del Monte. [15]

Archeological constraints

The presence of the castle's foundations reportedly may have thwarted the functional rehabilitation of the square, which should have become underground parking. Non-invasive solutions have been proposed in order to avoid damaging the historic heritage hidden underneath the square.[16]

References

- ↑ Image taken from Archivio Generalizio Agostininano - Angelica Library, Rome - Carte Rocca P/33 (pupillo-immagini, pag. 24)

- 1 2 3 Berloco 1985 p. 50 - note n. 62

- ↑ Berloco 1985 p. 50

- 1 2 3 4 Berloco 1985 p. 50 - note n. 63

- ↑ Orlandi 1770 p. 400

- ↑ Orlandi 1770 p. 402

- ↑ As written in the book Vita di Cola di Rienzo by an anonoymous author (vita-cola, p. 196).

- ↑ "Giovanni Pipino d'Altamura". 27 November 2012.

- ↑ Berloco 1985 p. 221 - Descrizione della città di Altamura - Registro dei fuochi - 1642

- ↑ "Il castello di Altamura. Mille anni sepolti nella dimenticanza della Storia".

- ↑ Berloco 1985 p. 51

- ↑ pupillo-immagini, pag. 25 (see also note 53)

- ↑ pupillo-immagini, pag. 25 (see also note 53)

- ↑ "Piazza Matteotti e la storia di un castello sotto il suo suolo". 21 June 2013.

- ↑ Merra, 1964 pag. 15

- ↑ "Il parcheggio sotterraneo in piazza Matteotti... Sì". 9 June 2011.

Bibliography

- Pupillo, Giuseppe (2017). Altamura, immagini e descrizioni storiche (PDF). Matera: Antezza Tipografi. ISBN 9788889313282. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-10-21. Retrieved 2018-10-21.

- Berloco, Tommaso (1985). Storie inedite della città di Altamura. ATA - Associazione Turistica Altamurana Pro Loco.

- Orlandi, Cesare (1770). Delle città d'Italia e sue isole adjacenti [sic] compendiose notizie - Tomo primo.

- Merra, Vincenzo (1964). Castel del Monte presso Andria. Molfetta: Scuola Tipografica Istituto Apicella per Sordomuti.