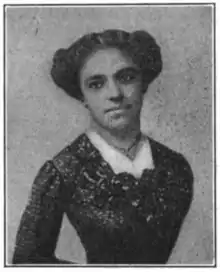

Amanda Gray Hilyer | |

|---|---|

Pictured in the Pharmaceutical Era, 1912 | |

| Born | Amanda Victoria Brown 24 March 1870 |

| Died | 29 June 1957 |

| Resting place | Columbian Harmony Cemetery |

| Alma mater | Howard University |

| Occupation(s) | Entrepreneur, pharmacist, civic worker, civil rights activist |

| Organization(s) | NAACP, Phillis Wheatley YWCA, National Medical Association |

| Known for | Being the first African American woman to own and operate a pharmacy in Washington D.C. |

| Spouse(s) | Arthur S Gray (1893–1917) Andrew F. Hilyer (1923–1925) |

Amanda Gray Hilyer (24 March 1870 – 29 June 1957)[1] was an African American entrepreneur, pharmacist, civic worker, and civil rights activist.[2] She was the first black woman to own and operate a pharmacy in Washington D.C.[3]

Early life

Amanda Victoria Brown[1] was born in Atchison, Kansas on 24 March 1870.[4] She attended public schools in Kansas and married, aged 23 in 1893,[2] pharmacist Arthur S. Gray (1869–1917).[1] In around 1897, the couple moved to Washington D.C., and she attended Howard University.[5] She obtained her pharmaceutical graduate degree in 1903.[5]

Washington D.C.

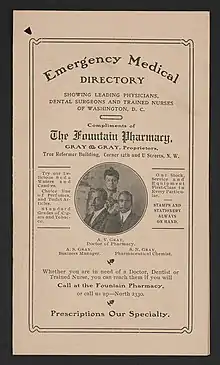

Gray initially worked as a pharmacist for the Woman's Clinic in Washington, before partnering with Arthur and opening the Fountain Pharmacy in 1905.[6] The Grays' pharmacy, at 12th and U Streets NW, sat in the heart of the black commercial district,[5] and the couple became an active part of Washington's African American elite.[6] Fountain Pharmacy was described as:

a large, bright, airy, well-equipped store that compares with any in the city. Aside from the prescription department, in which are two regular and two relief clerks, [it] has a branch post office, telegraph office and laundry agency.

The couple were involved in a variety of social, civic, and professional organizations, including the National Medical Association, the NAACP, and the Samuel Coleridge-Taylor Choral Society.[6] Arthur Gray acted as treasurer of the latter society.[7] Gray acted as secretary of the Treble Clef Club, and was a member of the Booklovers Club.[5] She helped to establish the Phillis Wheatley Young Women's Christian Association (YWCA) in Washington, and became its first recording secretary in 1905.[5]

After Arthur's death in 1917,[1] at the age of 48, Gray closed the pharmacy they had operated together.[3] She joined World War I efforts, and became a director of YWCA camp hostesses for Black soldiers.[3] She went on to become President of the Phillis Wheatley YWCA, holding the position for three years.[3]

In 1923, Gray married Andrew Franklin Hilyer (1858–1925),[1] a lawyer, author, and civil rights leader, who had been born enslaved.[4] Hilyer and his first wife, Mamie, had been known to the Grays, and active in many of the same circles.[4] Andrew F. Hilyer died in 1925, after two years of marriage.[4]

Post-1925

Hilyer continued her civic and social activities, and was active in a wide range of organizations.[4] She was a life-member of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History,[8] and President and member of the board of the Ionia R. Whipper Home for Unwed Mothers.[4] Ionia Rollin Whipper (1872-1953) was Hilyer's contemporary at Howard University, and was herself a reformer.[4] She was a member of the Citizens Committee for Freedmen's Hospital Nurses,[4] the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses, and President of the Alumni Association at Howard University.[3] Hilyer was a member of the Inter-Racial Committee of the District of Columbia, organized by the NAACP,[9] of which she was a life-member.[4] She was also involved in helping to preserve the Frederick Douglass House in Anacostia.[4]

Death and legacy

Gray Hilyer died at home on 29 June 1957, after suffering a stroke.[4] She was 87 years old.[4] Her beneficiaries included Berean Baptist Church, where her funeral was held, and to which she funded a window in memory of her husband, Arthur Gray.[4] She also left significant contributions to the Ionia Whipper Home, and to Howard University, as well as fifty dollars each to the Phillis Wheatley YWCA and Stoddard Baptist Home.[4] She was buried in Columbian Harmony Cemetery, with her first husband.[4] She was remembered as a woman who 'dedicated her life to the educational, social, and moral uplift of black people, particularly those in Washington D.C'.[4]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Amanda Victoria Brown Gray Hilyer (1870-1957)". www.findagrave.com. Retrieved 2021-03-15.

- 1 2 Jack Rummel (2003). African-American social leaders and activists. Internet Archive. Facts On File. ISBN 978-0-8160-4840-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Black History Month Spotlight: Three Black Women Who Forged their Way in Pharmacy". BioMatrix Specialty Pharmacy. Retrieved 2021-03-15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Smith, Jessie Carney (1992). Notable Black American women. Internet Archive. Deroit : Gale Research. ISBN 978-0-8103-4749-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 McGuire, Robert G. (2005). "Hilyer, Amanda V(ictoria) Gray". Oxford African American Studies Center. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195301731.013.41667. ISBN 978-0-19-530173-1. Retrieved 2021-03-15.

- 1 2 3 Vu, Angel (2017-06-01). "A Family of Pharmacists | Inside Adams: Science, Technology & Business". blogs.loc.gov. Retrieved 2021-03-15.

- ↑ The Crisis 1925-11: Vol 31 Iss 1. Internet Archive. The Crisis Publishing Company. 1925.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Woodson, C. G. (1931). "Annual Report of the Director". The Journal of Negro History. 16 (4): 349–358. doi:10.1086/JNHv16n4p349. ISSN 0022-2992. JSTOR 2713866. S2CID 224837053.

- ↑ "Letter from NAACP Inter-racial Committee to W. E. B. Du Bois, September 14, 1940". credo.library.umass.edu. Retrieved 2021-03-15.