Amastia refers to a rare clinical anomaly in which both internal breast tissue and the visible nipple are absent on one or both sides. It affects both men and women. Amastia can be either isolated (the only medical condition) or comorbid with other syndromes, such as ectodermal dysplasia, Syndactyly (Poland's syndrome) and lipoatrophic diabetes.[1] This abnormality can be classified into various types, and each could result from different pathologies.[2] Amastia differs from amazia and athelia. Amazia is the absence of one or both mammary glands but the nipples remain present, and athelia is the absence of one or both nipples, but the mammary gland remains.[3]

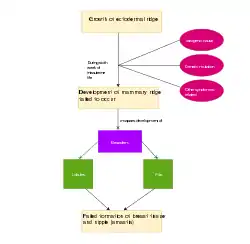

Amastia is presumably due to failure of embryologic (before birth) mammary ridge development or incomplete involution. People with amastia often suffer from ectodermal defects, which include various syndromes such as cleft palate, isolated pectoral muscle and abnormal formation of the arms.[4]

Treatment for female amastia particularly includes psychological guidance and breast reconstruction.[1] Because there is no breast tissue, breastfeeding is not possible. If amastia only appears on one side, then it is possible to breastfeed on the other side. Often, people with amastia decide against treatment.

Classification

Amastia can be either iatrogenic or congenital.[1] The congenital amastia are further divided into syndromic type and non-syndromic type respectively.

As the definition suggests, syndromic amastia is often associated with obvious symptoms. The common case is hypoplasia of ectodermal tissue, such as hair and skin defects.

On the other hand, non-syndromic amastia, shows no defects in body parts other than breast. This type of amastia can be further classified into unilateral and bilateral amastia. Unilateral amastia can be defined as amastia involving only one side of breast, while bilateral type refers to amastia on both sides of breast.[5] Unilateral amastia is less common than bilateral amastia. Almost all the non-syndromic amastia patients are female.[6]

Signs and symptoms

Typically, amastia patients have both their nipple and areola missing, and the nipple may be absent on one or both sides of the breasts. Abnormalities are not often associated with the breasts. However, symptoms such as hypertelorism, saddle nose, cleft palate, urologic disorders and dysfunction of muscle, upper and lower limb have been observed. Sometimes several members of a family can be diagnosed as amastia simultaneously, all of them are carriers of mutations in TBX3 gene. This mutation could cause various abnormalities, not only amastia, but also deformation of limb and teeth.[4][6]

Cases of unilateral amastia are uncommon, and they are often associated with hypoplasia of pectoral major muscle and/or the thorax. Bilateral amastia is more common because it is often associated with other different syndromes. Therefore, the symptoms of bilateral amastia are easier to be diagnosed.[5] Various associated syndromes are listed below.

Associated syndromes

Amastia, particularly if it is bilateral, often related to various syndromes, including ectodermal dysplasia and Poland's syndrome, which is characterised by anomalies of underlying mesoderm and abnormal pectoral muscle respectively.[7] Other syndromes, such as FIG4 associated Yunis Varon syndrome (MIM 216340), acro-der-mato-ungual-lacrimal-tooth (ADULT) syndrome, TP63 associated limb mammary syndrome (MIM 603543), TBX3 associated ulnar syndrome (MIM 181450) and KCTD1 associated scalp-ear-nipple syndrome (MIM 181270) have also been clinically observed.[3]

Ectodermal dysplasia

Ectodermal dysplasia is commonly associated with syndromic amastia. The symptoms of ectodermal dysplasia can be referred to abnormal development of several ectodermal-derived structure such as hair, teeth, nails and sweat glands. Other symptoms may include the inability to sweat, vision or hearing loss, missing or underdeveloped fingers or toes and maldevelopment of breast tissue. Genetic mutations may cause ectodermal dysplasia, and these genes can pass from parents to children. The most common case is the mutation of EDA1 gene which is in X chromosome, and this mutation results in X-linked form hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (XLHED). There is strong association between amastia and XLHED. Over 30% male patients with XLHED have absent nipples. 79% female carriers decrease the ability of breastfeeding. This suggests people with amastia should have a comprehensive skin test to exclude this syndrome.[7]

Poland's syndrome

Poland's syndrome is a genetic disorder associated with abnormal breast development. The prevalence rate of this syndrome is approximately 1 in 20000 to 30000. Both chest wall and upper limb lost normal function, and this syndrome usually occurs unilaterally. Mild and partial forms of Poland's syndrome are common, which often been undiagnosed because the clinical feature is only breast asymmetry and a horizontal anterior axillary fold, without severe symptoms. Other abnormalities include deformation of ribs, absence of pectoralis muscle, hypoplasia or abnormalities of breast and subcutaneous tissue. Patients may also have webbed fingers on one hand, short bones in the forearm or sparse underarm hair.[2][8]

Al Awadi/Raas-Rothschild syndrome

Al Awadi/Raas-Rothschild syndrome is a rare genetic disorder. Symptoms are often associated with absence or maldevelopment of skeletal part of limbs.[9]

Scalp-ear-nipple syndrome

As the name suggests, Scalp-ear-nipple syndrome is characterized by congenital absence of skin, abnormalities of scalp, malformation of ear structures, and undeveloped nipples.[9]

Mechanism

Mammary glands are arranged in breasts of the primates to produce milk for feeding offspring. They are enlarged and modified sweat glands. In the embryological development, mammary glands firstly appear after six weeks of pregnancy in the form of ectodermal ridges. The ectodermal ridge grows thicker and compresses to form mesoderm. As the proliferation persists, mesodermal layer continues to form clusters. The clusters grow and become lobules. At the same time, the clusters also form a pit, which protrudes to generate the nipples. Impairment in some of these processes may cause aplasia of the breast tissue, which may result in amastia.[5]

For example, in normal condition, mammary ridge (milk line) would extend from the bilateral axillary tail to the inguinal region. If this extension does not occur in normal way, the breast would not develop successfully.[4][7]

Amastia may also be caused by the inability of producing parathyroid hormone related protein. The absence of this protein will disrupt the normal development of mammary gland. Therefore, when amastia patients receive medical ultrasound examination, asymmetry or disproportioned mammary tissue may be found.[9]

Causes

Unilateral amastia is usually caused by Poland's syndrome, which is characterized by one side absence of breast. The absence or dysfunction of pectoralis muscle and ribs are common case. It can also be part of other syndromes as described in the previous contents.

Other causes may include intrauterine exposure to teratogenic drugs such as Dehydroepiandrosterone and methimazole / carbimazole treatment during first trimester.[1]

For bilateral amastia, the cause has not been well understood so far. It may be related to gene mutation since often patients with bilateral amastia are diagnosed as autosomal dominant and recessive inheritance. Decreasing blood flow in the subclavian artery may also be a cause of amastia.[1]

Amastia can also be caused by injuries. These injuries may happen when patients receive surgery, such as thoracotomy, chest tube placement, or when they are treated by radiotherapy. Improper biopsy or severe burns of breast tissue may also result in amastia.[10]

Genetics

Congenital amastia can be associated with both autosomal dominant and recessive inheritance. However, in clinical research, autosomal recessive heritage amastia is uncommon.[3]

Mutation of genes may disrupt the normal process and results in abnormity of breast. The protein tyrosine receptor type F gene (PTPRF) is particularly important in nipple-areola region development. PTPRF encodes protein phosphatase which can localize at adherent junction. This phosphatase may also regulate epithelial cell to enable cell- cell interaction. PTPRF is also responsible for growth factor signalling and Wnt pathway. Homozygous frameshift mutation in PTPRF may cause amastia, which suggests the causative relationship between PTPRF defect and syndromic amastia.[3]

Management

Since bilateral and unilateral amastia may be attributed to different pathologies, appropriate managements should be adopted accordingly. Bilateral amastia can occur in isolation or associated with other disorders. This case is less understood and difficult to treat. On the other hand, Poland's syndrome is the most common cause of unilateral amastia. Managements such as muscle/breast reconstruction and nipple areola relocation should be provided to these patients.[2]

Breast reconstruction

Surgical treatment for breast defects such as mastectomy is also applicable to treat patients with amastia. Tissue expansion is the most common technique and can be done by using either autologous or prosthetic tissue. For autologous reconstruction, different tissues may be chosen according to patients’ physical condition or their preferences. Prosthetic reconstruction may follow the same principles.[2] Flap reconstruction is another method to rebuild the breast surgically. There are various kinds of flaps to choose depending on different situation.[5]

Nipple areola relocation

Amastia is often associated with Poland's syndrome, which requires appropriate reconstructive procedure to stabilize chest wall, transfer dynamic muscle and reposition nipple areola region. The treatment of nipple areola relocation provides space for secondary breast enlargement. In this treatment, the tissue expander can be inserted either beforehand or delayed. It can be placed in different parts of body depending on how many overlying soft tissues the patient has. In order to guide the dissection and make sure the correct location of these tissues, marking of the inframammary crease is required before operation.[2]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Patil LG, Shivanna NH, Benakappa N, Ravindranath H, Bhat R (October 2013). "Congenital amastia". Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 80 (10): 870–1. doi:10.1007/s12098-012-0919-1. PMID 23255076. S2CID 44908103.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Caouette-Laberge L, Borsuk D (February 2013). "Congenital anomalies of the breast". Seminars in Plastic Surgery. 27 (1): 36–41. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1343995. PMC 3706049. PMID 24872738.

- 1 2 3 4 Borck G, de Vries L, Wu HJ, Smirin-Yosef P, Nürnberg G, Lagovsky I, Ishida LH, Thierry P, Wieczorek D, Nürnberg P, Foley J, Kubisch C, Basel-Vanagaite L (August 2014). "Homozygous truncating PTPRF mutation causes athelia". Human Genetics. 133 (8): 1041–7. doi:10.1007/s00439-014-1445-1. PMID 24781087. S2CID 2810158.

- 1 2 3 Carr RJ, Smith SM, Peters SB (2018). Primary and Secondary Dermatologic Disorders of the Breast. Elsevier. pp. 177–196.e7. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-35955-9.00013-1. ISBN 9780323359559.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - 1 2 3 4 Hatano A, Nagasao T, Sotome K, Shimizu Y, Kishi K (May 2012). "A case of congenital unilateral amastia". Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery. 65 (5): 671–4. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2011.09.025. PMID 22051444.

- 1 2 Sun SX, Bostanci Z, Kass RB, Mancino AT, Rosenbloom AL, Klimberg VS, Bland KI (2018). Breast Physiology. Elsevier. pp. 37–56.e6. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-35955-9.00003-9. ISBN 9780323359559.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - 1 2 3 Al Marzouqi F, Michot C, Dos Santos S, Bonnefont JP, Bodemer C, Hadj-Rabia S (September 2014). "Bilateral amastia in a female with X-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia". The British Journal of Dermatology. 171 (3): 671–3. doi:10.1111/bjd.13023. PMID 24689965. S2CID 37997710.

- ↑ Mansel, R.E.; Webster, D.J.T.; Sweetland, H.M.; Hughes, L.E.; Gower-Thomas, K.; Evans, D.G.R.; Cody, H.S. (2009), "Congenital and growth disorders", Hughes, Mansel & Webster's Benign Disorders and Diseases of the Breast, Elsevier, pp. 243–256, doi:10.1016/b978-0-7020-2774-1.00019-0, ISBN 9780702027741

- 1 2 3 Ishida LH, Alves HR, Munhoz AM, Kaimoto C, Ishida LC, Saito FL, Gemperlli R, Ferreira MC (September 2005). "Athelia: case report and review of the literature". British Journal of Plastic Surgery. 58 (6): 833–7. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2005.01.018. PMID 15950955.

- ↑ Brandt ML (2012). "Disorders of the Breast". Pediatric Surgery (7th ed.). Elsevier. pp. 771–778. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-07255-7.00061-1. ISBN 9780323072557.