Ambidextrous leadership is a recently introduced term by scholars[1] to characterize a special approach to leadership that is mostly used in organizations.[2] It refers to the simultaneous use of explorative and exploitative activities by leaders. Exploration refers to search, risk taking, experimentation, and innovation in organizations, whereas exploitation has to do with refinement, efficiency, implementation, and execution.[3] Successful ambidextrous leaders must be able to achieve the appropriate mix of explorative and exploitative activities, unique for each organization, that will lead them to high firm performance outcomes.[4]

Ambidextrous leadership at multiple levels

Within the context of an organization, efficient management of ambidexterity is needed at all hierarchical levels.[5] Scholars, however, emphasize that organizational ambidexterity and ambidextrous leadership are two different concepts not necessarily related. According to researchers, different organizational levels may need different behaviors on behalf of individuals to manage ambidexterity,[6][7] as ambidexterity management is important in a different degree for each level. If, however, leaders manage to achieve the proper balance of explorative and exploitative activities at their level, then ambidexterity may effectively penetrate at the lower levels of their organization.[5]

Ambidextrous leadership on the micro-level

On the individual level of analysis, scholars have mostly used paradox theory to explain how individuals manage the competing demands of exploration and exploitation.[8][9] Paradoxical leadership refers to seemingly competing, yet interrelated behaviors to meet structural and follower demands simultaneously and over time.[10] Managing complex business models effectively depends on leadership that can make dynamic decisions, build commitment to specific visions and goals, learn actively at multiple levels, and engage conflict.[11]

On the group level of analysis, scholars have examined how team members affect leadership actions in the promotion of ambidexterity. Many researchers have focused their attention on the heterogeneity of both board of directors and top management teams. Research has shown that when the functional background heterogeneity of boards of directors is included into the strategy-making, then their knowledge resources can contribute to the relative exploration orientation of an organization[12][13] In the same vein, top management teams heterogeneity moderates the impact of the internal and external advice seeking on the exploratory innovation.[14]

Ambidextrous leadership on the macro-level

The roles and behaviors of effective top managers differ considerably from those of middle managers.[15][16] This can be attributed to the fact that middle managers have different priorities from senior executives[17] When ambidexterity penetrates across level, explorative and exploitative knowledge sharing of middle managers is especially important for the long-term firm performance.[18] For example, top-down knowledge inflows of managers from the higher hierarchical levels positively relate to middle managers' exploitative activities, while bottom-up and horizontal knowledge inflows from lower levels and peers positively relate to their explorative activities.[7]

On the employee level of analysis, both psychological factors and paradoxical leadership of group managers predict employees’ ambidextrous behavior.[19] For instance, ex-ante incentives (incentives based on past performance) and ex-post incentives (incentives based on future performance) affect productivity, motivation, and performance of employees, while making them feel the sense of stretch essential in building an ambidextrous organization.[20]

Ambidextrous leadership from a multi-level perspective

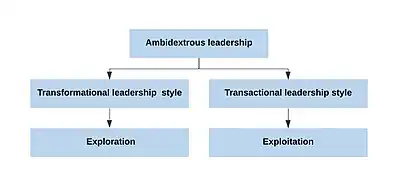

From a multi-level perspective, many scholars have used the concept of strategic leadership to explain ambidexterity management. Strategic leadership extends the upper echelons theory and includes chief executive officers, board of directors and top management teams. This concept includes both the micro- and the macro- perspectives of leadership behaviors.[21] On the micro-level, researchers have used transformational and transactional leadership styles,[22] while on the macro-level, they have included specific moderators, such as organizational size, structure, strategy, and external environment. [5][23] Some scholars have also used a multi-dimensional construct of dynamic capabilities to explain ambidexterity management and long-term firm performance,[24] as well as short-term and long-term tensions within the context of the temporal ambidexterity.[25]

As researchers explain, transformational leadership behaviors are needed for exploration. They refer to a set of leaders’ roles or behaviors that influence, encourage, support and guide followers to think differently, experiment and innovate, think independently, creatively and out of the box, challenge the status quo and the existing mindsets. On the contrary, transactional leadership behaviors are required for exploitation. This includes objective setting, sticking to plans, monitoring and controlling adherence to rules by the followers, supervising cost reductions, taking corrective actions, and establishing procedures and routines. Leaders’ ambidexterity management has to do with the simultaneous use of these two contradictory yet complementary leadership styles.[23]

References

- ↑ Rosing, K., Frese, M., & Bausch, A. (2011). Explaining the heterogeneity of the leadership-innovation relationship: Ambidextrous leadership. The Leadership Quarterly. 22(5), 956–974.

- ↑ Kassotaki, O. (2019a). Ambidextrous leadership in high technology organizations. Organizational Dynamics, 48(2), 37-42.

- ↑ March, J. G. (1991). Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science, 2 (1), 71-87.

- ↑ Raisch, S. & Birkinshaw, J. (2008). Organizational ambidexterity: Antecedents, outcomes and moderators. Journal of Management, 34(3), 375-409.

- 1 2 3 Kassotaki et al. (2019). Ambidexterity penetration across organizational levels in an aerospace and defense organization. Long Range Planning, 52 (3), 366-385.

- ↑ Lubatkin, M. H., Simsek, Z., Ling, Y., & Veiga, J. (2006). Ambidexterity and performance in small- to medium-sized firms: The pivotal role of top management team behavioral integration. Journal of Management. 32(5), 646–672.

- 1 2 Mom, T., Van Den Bosch, F., & Volberda, H. (2007). Investigating managers’ exploration and exploitation activities: The influence of top-down, bottom-up and horizontal knowledge inflows. Journal of Management Studies. 44(6), 910–931

- ↑ Lewis, M. W., Andriopoulos, C., & Smith, W. K. (2014). Paradoxical leadership to enable strategic agility. California Management Review. 56(3), 58–77.

- ↑ Smith, W. (2014). Dynamic decision making: A model of senior leaders managing strategic paradoxes. Academy of Management Journal. 57(6), 1592–1623.

- ↑ Zhang, Y., Waldman, D., Han, Y., & Li, X. B. (2015). Paradoxical leader behaviors in people management: Antecedents and consequences. Academy of Management Journal. 58(2), 538–566.

- ↑ Smith, W., Binns, A., & Tushman, M. (2010). Complex business models: Managing strategic paradoxes simultaneously. Long Range Planning. 43(2–3), 448–461.

- ↑ Heyden, M. L. M., Oehmichen, J., Nichting, S., & Volberda, H. W. (2015). Board background heterogeneity and exploration-exploitation: The role of the institutionally adopted board model. Global Strategy Journal. 5(2), 154–176.

- ↑ Oehmichen, J., Heyden, M. L. M., Georgakakis, D., & Volberda, H. W. (2017). Boards of directors and organizational ambidexterity in knowledge-intensive firms. International Journal of Human Resource Management. 28(2), 283–306.

- ↑ Alexiev, A., Jansen, J., Van den Bosch, F., & Volberda, H. (2010). Top management team advice seeking and exploratory innovation: The moderating role of TMT heterogeneity. Journal of Management Studies. 47(7), 1343–1364.

- ↑ Andriopoulos, C., & Lewis, M. (2009). Exploitation-exploration tensions and organizational ambidexterity: Managing paradoxes of innovation. Organization Science. 20(4), 696–717.

- ↑ Papachroni, A., Heracleous, L., & Paroutis, S. (2016). In pursuit of ambidexterity: Managerial reactions to innovation-efficiency tensions. Human Relations 69(9), 1791–1822.

- ↑ Yukl, G., & Mahsud, R. (2010). Why flexible and adaptive leadership is essential. Consulting Psychology Journal.62(2), 81–93.

- ↑ Im, G., & Rai, A. (2008). Knowledge sharing ambidexterity in long-term interorganizational relationships. Management Science. 54(7), 1281–1296.

- ↑ Kauppila, O. P., & Tempelaar, M. P. (2016). The social-cognitive underpinnings of employees’ ambidextrous behaviour and the supportive role of group managers’ leadership. Journal of Management Studies. 53(6), 1019–1044.

- ↑ Ahammad, M., Lee, M., Malul, M., & Shoham, A. (2015). Behavioral ambidexterity: The impact of incentive schemes on productivity, motivation, and perfrmance of employees in commercial banks. Human Resource Management. 54(S1), 45–62.

- ↑ Crossan, M., Vera, D., & Nanjad, L. (2008). Transcendent leadership: Strategic leadership in dynamic environments. Leadership Quarterly. 19, 569–581.

- ↑ Jansen, J., Vera, D., & Crossan, M. (2009). Strategic leadership for exploration and exploitation: The moderating role of environmental dynamism. The Leadership Quarterly. 20(1), 5–18.

- 1 2 Kassotaki, O. (2019b). Explaining ambidextrous leadership in the aerospace and defense organizations. European Management Journal. 37(5), 552–563.

- ↑ Eisenhardt, K., Furr, N., & Bingham, C. (2010). Microfoundations of performance: Balancing efficiency and flexibility in dynamic environments. Organization Science. 21(6), 1263–1273.

- ↑ Wang, S., Luo, Y., Maksimov, V., Sun, J., & Celly, N. (2019). Achieving temporal ambidexterity in new ventures. Journal of Management Studies. 56(4), 788–822.